Baseline Study

- Study Overview

This baseline study was designed to investigate the procrastination habits of college students, aiming to understand the underlying reasons for their procrastination, how it impacts their academic performance and well-being, and what practical steps they can take to manage it more effectively. The study sought to identify patterns in students’ procrastination behaviors, explore the emotions and thoughts associated with task avoidance, and evaluate potential interventions or strategies that could help students improve their time management skills.

By focusing on self-reflection and tracking daily habits, the study aimed to provide insights into how procrastination manifests in students’ daily lives and what factors contribute to or hinder their ability to complete tasks efficiently. We recognize that procrastination takes many different forms and is influenced by a variety of triggers, ranging from academic pressure to personal habits and environmental factors. Our study methodology was carefully designed to capture these nuances through structured data collection methods, including diary tracking, interviews, and surveys.

By employing a multi-faceted approach, we aimed to uncover both common and individualized procrastination patterns, allowing for a deeper understanding of the challenges students face. In the following sections, we outline the specific techniques used to gather data and analyze procrastination behaviors, providing a foundation for developing targeted interventions that can help students manage their time more effectively.

- Study Methodology

The study employed a four-day diary study format, beginning with a pre-study interview to establish a baseline understanding of each participant’s experiences, perspectives, and self-awareness of procrastination. These preliminary interviews provided insights into participants’ existing habits and their perceived challenges with task management.

Each morning, participants documented their intended tasks for the day, noting their top priorities and the reasons for selecting them. This process was designed to help participants organize different priorities, particularly action items that might otherwise be forgotten in the grand scheme of their workload. Writing down tasks also served as an accountability measure, as the act of recording them reinforced memory retention and intention. In the evening, participants reflected on their day by identifying which tasks they completed, which they procrastinated on, and when they were most productive. They were encouraged to explore the emotions and thoughts accompanying their procrastination to uncover underlying trends. This reflection process aimed to identify recurring patterns in procrastination and whether certain types of tasks were consistently avoided. Participants were provided with structured handouts to ensure consistency in documentation, and daily reminders encouraged them to complete both the morning planning and evening reflection exercises. To complement these self-tracking efforts, they also assessed the percentage of tasks completed and described how that percentage influenced their emotions and overall sense of productivity.

At the end of the study, a 30-minute post-study interview was conducted to analyze participants’ experiences, discuss observed patterns, and evaluate any behavioral changes that occurred over the four-day period. This concluding phase allowed for deeper insights into how self-reflection influenced procrastination habits and provided additional context for the qualitative and quantitative data collected throughout the study.

- Participant Recruitment

The study targeted college students who identified as habitual procrastinators and were open to reflecting on their behaviors. Recruitment focused on individuals who frequently delayed important tasks, acknowledged that procrastination negatively impacted their academic performance or well-being, and expressed a willingness to track and analyze their habits over the course of the study. A screener questionnaire was used to ensure that participants met these criteria, helping to establish a sample that accurately represented students struggling with procrastination. The recruitment process emphasized voluntary participation, ensuring that all individuals involved were genuinely interested in understanding their procrastination tendencies and exploring ways to manage them more effectively.

- Key Research Questions

The baseline study was structured around several core research questions. First, it sought to determine the primary reasons students procrastinate, investigating whether external factors (such as distractions and workload) or internal factors (such as stress, fear of failure, or perfectionism) played a more significant role. Additionally, the study aimed to understand how procrastination impacted students’ productivity and emotional well-being, examining whether delaying tasks led to increased stress, decreased academic performance, or other negative consequences. Another key focus was identifying moments of peak productivity and exploring whether specific conditions—such as time of day, environment, or mindset—correlated with better task completion. Finally, the study sought to evaluate how self-awareness and reflection influenced procrastination habits. By asking participants to document and assess their behaviors over multiple days, the study aimed to determine whether engaging in structured reflection led to any noticeable shifts in their procrastination patterns or motivation levels.

By addressing these research questions, the study provided a foundational understanding of procrastination among college students, offering insights that could inform future interventions, tools, or strategies to help students manage their time more effectively.

-

Raw Data -> Grounded Theory

Following our experiment, we intend to synthesize insights from the data regarding stress, social interactions, and productivity in relation to procrastination. We started with Affinity Grouping to flesh out and organize all the different data points we covered across our interviews. Below you’ll see a picture of our first Affinity Map, as well as a bulleted list of our largest takeaways following the mapping session.

Affinity Mapping:

Key Takeaways from Affinity Mapping:

-

Social pressure can have a large impact on combatting procrastination

-

The effort needed to begin a task is often the limiting factor – this comes out both in large and small tasks, getting started can often be the hardest part

-

Procrastination can be tied together with self worth

-

It can serve as a form of self sabotage/punishment

-

-

People rely on a variety of different tools to combat their procrastination problems

-

Procrastination problems remain prevalent because people still find a way to get their work done, reinforcing this behavior

-

People procrastinate different kinds of tasks

-

Large, stressful tasks (Exams, papers, applications, etc)

-

Small tasks (laundry, emails, etc)

-

The goal of this synthesis is to better understand student needs, pinpoint challenges, and explore potential interventions that could improve student well-being. Because of this, we will take a deeper look into some key theories and insights that could come from the Key Takeaways we gained through our Affinity Mapping.

Grounded Theory 1: Effort is a key determinant of procrastination

-

Subtheory: The greater the perceived effort required for a task, the more likely students are to procrastinate.

-

Example: Tasks that require extensive time, cognitive load, or physical effort—such as going to office hours or starting a large assignment—are frequently postponed in favor of smaller, easier-to-complete tasks. This trend suggests that the perception of effort plays a significant role in task avoidance.

-

One of our participants Iman talked about how she would procrastinate laundry much more frequently this year than last year because she lived only a few further doors down from the laundry room this year. This matched with literature we have read in class related to procrastination.

-

Another one of our participants, Susan, talked about how they struggle with starting things and how she makes things out to be a bigger task in her head. For example the perceived effort of going to office hours felt like it would be eating into too much of her day, when in reality it would have been a 1-2 hour excursion, or sometimes just a short email to a TA away from understanding a concept or completing her work.

-

Question(s): What emotions/feelings/experiences cause people to overestimate the perceived effort of a task? Is it coming from a place of anxiety? Why can’t people be realistic about time allocation since that would help them plan better?

-

-

Grounded Theory 2: Social pressure influences procrastination behavior

-

Subtheory: Students will sometimes create unnecessary work for themselves because they feel pressure to appear busy and productive

-

Example: Feelings of unworthiness in higher academic institutions, also known as “duck syndrome” causes some students to believe that they do not deserve to be at their respective institutions, which can subconsciously lead to these students over-complicating their work with procrastination in order to feel busy. This is also related to the feeling of guilt when students have free time.

-

For example, Iman mentioned feeling that “everyone around me is doing so much, and if I take a break, I feel like I’m falling behind.” Rather than taking strategic breaks, students may avoid work entirely as a response to burnout.

-

Question: How does the pressure to constantly achieve contribute to cycles of procrastination?

-

-

-

Subtheory: Students are more likely to work on an assignment if they see their peers making progress on it.

-

There is a strong social influence on task initiation. When students observe their classmates discussing an assignment or making progress, they feel pressured to

- start their own work to avoid falling behind. Conversely, if they perceive that their peers are also procrastinating, they feel less urgency to begin.

- This was evident in one participant’s case, where she stated, “Once I found out that my peers had already finished most of the assignment I decided to skip lunch to work on it because I suddenly felt like ahhh… I’m falling behind.”

- Question: What role does peer influence play in shaping students’ procrastination habits?

-

Grounded Theory 3: Procrastination as a form of self-sabotage and self-worth struggle

- Subtheory: Some students procrastinate as an act of self-deprecation, reinforcing negative self-perceptions.

- For certain individuals, procrastination is not just about task avoidance but also tied to feelings of inadequacy. When students struggle with an assignment, they may spiral into self-doubt, which leads to further procrastination. This cycle can be exacerbated by imposter syndrome and duck syndrome.

- Susan, for instance, shared that “when I don’t understand something right away, I start thinking maybe I’m just dumb. Then I avoid it completely, which makes it worse.” She also stated that “Sometimes I don’t let myself go to the restroom until I finish a certain amount of work. Or like I won’t do something fun if I don’t think I deserve it and I end up doing nothing. Similarly, Iman noted that “sometimes I just feel like there’s no point in trying because I don’t even know if I’ll end up getting it.”

- Question: How does self-worth impact procrastination behaviors, and how can interventions target these beliefs?

Grounded Theory 4: The inevitability mindset—“It will get done eventually”

- Subtheory: Some students embrace last-minute stress as an unavoidable part of their process.

- Rather than viewing procrastination as a problem, some students see it as an integral part of their workflow. They believe they will always finish their tasks in time, even if it means enduring high levels of stress at the last minute.

- Tina described this mindset by saying, “I think at the end of the day, things have always gotten done. They’re not always done well…[but] I’ve been making by just fine. So it’s like, I’ve never felt the need to seriously reevaluate my [procrastination] there.

- Question: How does the belief in eventual task completion influence students’ motivation to adopt better time management strategies?

Grounded Theory 5: People prioritize tasks they feel competent in

- Subtheory: Students naturally gravitate toward work they feel confident completing, often at the expense of more pressing but difficult tasks.

- Rather than tackling high-priority assignments, students may first complete tasks that allow them to feel accomplished. This can lead to a pattern of avoiding more difficult work in favor of tasks that provide immediate validation.

- Luke mentioned that he likes to start with things he knows he can do well, just to get into the groove. Similarly, he said if he feels stuck, he will switch to something else he’s good at so he doesn’t feel like a failure.

- Question: How can interventions encourage students to face difficult tasks head-on rather than retreating to easier, confidence-boosting work?

- Luke mentioned that he likes to start with things he knows he can do well, just to get into the groove. Similarly, he said if he feels stuck, he will switch to something else he’s good at so he doesn’t feel like a failure.

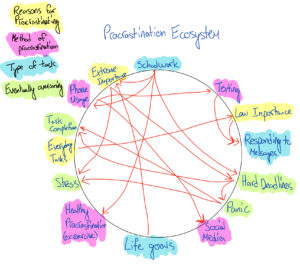

In this model, we created a procrastination ecosystem which highlights a handful of the factors that go into a typical process of procrastination. It starts with some type of task that is put off, either because it is too difficult, too boring, or just not that important. From there, many different distractions can aid in procrastination. Eventually, procrastination will end as the individual finally completes their task. There is usually a specific cause for their sudden completion of the task – often a deadline that brings about stress or panic for the individual, finally moving them to action. This diagram shows how similar processes of procrastination come about for different types of tasks, indicating that often it does not actually matter what is being procrastinated, as individuals become so accustomed to that way of operating.

This loop shows the dangerous cycle of procrastination that many students fall into. It is especially difficult to break free from this cycle because students will ultimately find success in the end. Whether it is turning in an assignment barely on time or successfully cramming for a final, students quickly forget about the stress that they endured as a result of their procrastination as soon as the task is out of their mind.

Here are some summarized key insights from both of these models:

- Panic can cause two opposite results – sometimes it can serve as a productive feeling that triggers action and task completion, otherwise it can be extremely unproductive triggering more stress without any pragmatic steps to completion.

- This made us think about why there is this discrepancy for different people at different times. This caused us to look more into why panic manifests itself into productive completion in some cases, and in other cases causes debilitating stress that stops people from getting anything done. We hypothesized that it may be different person-to-person, or perhaps could be related to the circumstances of the situation.

- After healthy forms of procrastination, people feel more equipped to deal with the task that they were procrastinating, as opposed to unproductive procrastination.

- As seen in our system model and confirmed through our baseline study, is that after productively procrastinating (doing laundry, cleaning room, responding to emails, etc), people felt far more equipped to face whatever tasks they were putting off. This makes us believe that productive procrastination could actually be a useful stepping block to addressing procrastination. We found repeatedly when people used unproductive procrastination (social media scrolling, etc), that there was less motivation and enthusiasm to break out of their procrastination and start the important task at hand.

- There is a reason that most procrastinators are serial procrastinators – the more experience they have procrastinating, the more false confidence they have in their ability to procrastinate.

- There seems to be a connection between procrastination and the sense of urgency that comes from working under pressure. Some students rely on this adrenaline rush to push them into action, which makes procrastination feel like an effective, if stressful, approach to work. This realization led us to think about how we could make not procrastinating just as engaging. If procrastination is thrilling because of the last-minute intensity, could we design a system that makes completing tasks ahead of time feel just as rewarding?

-

Secondary Research

Literature Review

- The study “Time Perspectives and Procrastination in University Students: Exploring the Moderating Role of Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction” by Codina et. al (2024) shows how perspectives on time can have a major impact on their procrastination habits

- A future time perspective, where students often think about the future, may indicate less procrastination

- This would support the value of goal setting – something that many competitor solutions have tried to address

- Encouraging a future oriented mindset may be apiece of the solution

- “Perceived Social support and procrastination in college students: A sequential Mediation Model of self compassion and negative emotions” by Yang et. al (2021)

- College students who feel that they have the support of family members behind them are less likely to procrastinate.

- This goes hand in hand with self-compassion – higher perceived social support is connected with higher self-compassion which together combat procrastination

- The opposite effect comes with isolation and negative emotions

- The study “Predictors of Academic Procrastination in College Students” by Saddler & Buley (1999) examines factors that contribute to procrastination among college students, focusing on perfectionism, motivation, and beliefs about learning.

- Focusing on extrinsic goals can actually reduce procrastination.

- Surprisingly, focusing on grades may help a student procrastinate less.

- Students who care deeply about the quality of work may suffer from perfectionism and have a harder time starting their work as they know it will take more effort from them.

- Procrastination and Stress: A Conceptual Review of Why Context Matters by Fuschia Sirois (2023)

- Stressful environments drain emotional and mental resources, making procrastination a tempting form of relief

- This only enhances stress, leading to a vicious cycle

Competitive Analysis

- 4 Main trends among competitors:

- Goal-oriented – These apps are focused on high level goals and allow a user to battle their procrastination from a top down approach

- These systems will often break down big goals into smaller, more attainable tasks

- Ex:

- Task-oriented – These apps prioritize daily tasks and planning. They focus more on the low-level tasks that a user may face and are more centered around day to day life

- Ex: Notion usually serves as a sort of note-taking and planning tool that will include everyday tasks from doing your laundry to stretching in the morning

- No Structure – These apps give users extreme flexibility in how they want to battle their procrastination

- There are usually a variety of different ways that these apps can be used and it is up to the user to determine what is the best approach for them

- Ex: Focus keeper uses a pomodoro timer to encourage users to stay focused during their work sessions; They specific work being completed and how long to set the timer is completely up to the user

- High Structure – The foundation and use cases for the app are well defined and do not offer the users as much flexibility in their interaction with the platform

- Ex: GoalsWon revolves around individual performance coaching and it is expected that all users use this feature.

- Goal-oriented – These apps are focused on high level goals and allow a user to battle their procrastination from a top down approach

- Notion (No-Structure + Tasks) is highly flexible but lacks predefined structures, requiring users to build their own workflow. These intervention applications are ideal for highly motivated and organized individuals who are looking for a place to fully maximize their thoughts.

- Focus Keeper and Forest (No-Structure + Goals) encourage focus through Pomodoro timers and gamification but do not provide structured goal tracking. These intervention applications are ideal for highly motivated goal oriented individuals who need a push to get started. Either social accountability or gamified time pressures helps to empower their willingness to achieve their goals.

- Opal, Griply, and GoalsWon (Structured + Goals) offer clear frameworks for reducing distractions (Opal) or habit-building (Griply, GoalsWon), with GoalsWon adding human accountability. These intervention applications are ideal for users who have a lot of goals they hope to accomplish, but lack the drive/discipline to overcome the persistent procrastination that stifles them. These serve are hardcore reminders and offer friction to procrastination triggers.

- Structured (Structured + Tasks) provides a built-in timeline-based planner for managing daily tasks, offering a more guided approach than Notion. These intervention applications are ideal for users who are highly motivated but lack the organizational skills to structure their commitments and goals.

How These Will Affect Our Ideation

Our research has shown that procrastination isn’t just about poor time management—it’s driven by effort perception, social pressure, self-doubt, and even the rush of last-minute adrenaline. Understanding these factors means that rather than simply designing a tool that reminds students to work, we need to create something that makes starting and completing tasks feel as rewarding as procrastinating.

One of the biggest reasons students put things off is the amount of effort a task seems to require. If something feels too difficult or time-consuming, they avoid it. To counter this, our solution needs to make getting started easier—whether by breaking tasks into smaller steps or making the first step feel more approachable. Social influence also plays a major role, as students are more likely to start working when they see their peers doing the same. This opens the door for features that leverage peer accountability or competition to create positive pressure.

A key insight from our study is that many procrastinators don’t feel urgency until the last minute because they believe they’ll always get things done. This false confidence keeps them stuck in a cycle of stress. Instead of relying on looming deadlines to create urgency, we need to introduce it earlier in a way that feels natural and motivating. Gamification might be one way to achieve this—by incorporating elements like point systems, progress tracking, or small challenges, we could create a sense of stakes much earlier in the process. If procrastinators thrive under pressure, the goal would be to bring that same level of engagement into working ahead rather than waiting until the last possible moment.

Another factor reinforcing procrastination is the excitement and adrenaline of last-minute work. While this is just one of many findings, it suggests that one way to counter procrastination is by making not procrastinating feel just as engaging. Whether through gamification, real-time feedback, or reward-based progress, we could explore ways to shift the excitement of last-minute scrambling into the experience of working ahead. This, along with all our other insights, will shape how we approach our ideation process.

Proto Personas and Journey Maps

For selecting our proto personas, we discussed all the personas we created and selected the most common problems faced from our users. Our first persona is Last Minute Larry, who struggles prioritizing work—waiting until the last minute to complete their work. An insight that last minute Larry showcases is a procrastination feedback loop—last minute Larry is able to successfully complete his work despite waiting until the last minute. This reinforces his behavior of waiting until the last minutes, leaving him in a perpetual state of procrastination.

Persona 1

| Name | Last Minute Larry |

| Activated Role | College Student |

| Goal | Complete things in as little time as possible, no matter how small or large the task is |

| Motivation | It feels good to avoid responsibilities and Larry believes that he will actually be more productive and efficient if he wait until the last minute |

| Conflict | Larry is conflict averse. He avoids his problems and puts things off until they are absolutely essential. This is likely because the effort it takes in his head is greater than the actual effort in practice |

| Attempts to Solve | His procrastination by writing down what he has to do in advance. This is not usually successful and he ends up forgetting about his list and then scrambles to get it all done in the end |

| Setting/ Environment | College campus |

| Tools | Calendar, iPhone, notes App |

| Skills | Extreme focus in extreme circumstances |

Journey Map

Throughout last minute Larry’s day, we see Larry’s perception of his time decrease. He wakes up believing there is ample time to complete his work. However, Larry exhibits an “I’ll get to it later” attitude when he believes he has the whole day. We see a transition into thinking about his work, but it is met with him needing a break from essentially not doing anything that tackles his work. In the end, Larry is scrambling to complete his work. Additionally, we see his emotion spiral into a panic as the day goes forth. His actions showcase a scrolling individual who is not prioritizing the assignments that are due that day. There is a lack of structure to his priorities. Last minute Larry has a tendency to falsely reward himself which may lead to him having a false sense of accomplishment.

Our second persona, Substantial Sally, embodies an archetype of someone who dreads big/substantial tasks: essays, exams, projects, applications, etc. The anxiety that comes from completing these seemingly monumental tasks, results in their reluctance to get started, which unravels into this negative feedback loop where the task gets even more monumental due to a time crunch. In the end, by overestimating the work needed to get done, Sally delays her tasks and is unable to productively and incrementally accomplish the major tasks she needs to complete in order to thrive and grow in the ways she hopes to.

Persona 2

| Name | Substantial Sally |

| Activated Role | College Student in STEM |

| Goal | I want to solve my procrastination habits because it would hope me succeed and thrive in my endeavors |

| Motivation | Career goals. |

| Conflict | Sally often underestimates time and effort needed for big tasks and assignments, meaning she delays her work and runs out of time and falls under tremendous pressure. |

| Attempts to Solve | Fill up blocks of time with small management tasks that could overcome procrastination |

| Setting/ Environment | In the dorm room, dining hall, classroom, library, etc |

| Tools | iPhone Notes app to map out my tasks, and Google Calendar to map out all commitments |

| Skills | Performs well under-pressure |

| More | N/A |

Journey Map

Throughout Sally’s day, she assumes she has the entire day ahead of her. She doom-scrolls and feels pretty optimistic about the day. As she gets ready for class, she thinks about her work, but realizes that the assignment requires too much effort. In between her classes, she is under the impression that there is not enough time to produce meaningful work. Then, later after class, Sally has to prepare herself to take on her task, but feels defeated. This unravels into a procrastination spiral of trying to finish her work, but feeling overwhelmed and anxious.