Team Rhebok – Synthesis

Problem Domain

Our project aims to help people think independently before directly using LLMs. To understand current “LLM-first” behaviors and the conditions under which people do or do not think first, we ran a baseline study centered on in-the-moment tracking of real LLM sessions, paired with pre- and post-interviews. The baseline study was designed to (a) capture how LLM use unfolds in everyday work/school contexts, (b) measure multiple dimensions of confidence and ownership surrounding each session, and (c) examine whether simply pausing to log can surface reflection or behavior change.

Baseline Study

1) Study Methodology

Method: 5-day diary study + semi-structured pre- and post-interviews.

Diary study (in-situ logging): Participants were asked to log every chatbot session they started for 5 consecutive days (~5 min/day). Each entry captured both context (what task, why they used an LLM, importance) and multi-dimensional self-ratings (confidence, satisfaction, correctness, efficiency, comfort sharing, ownership), plus time spent.

Pre-interview (~30 min): established baseline usage patterns and decision-making, with emphasis on what “confidence” means to participants and what triggers habitual LLM use.

Post-interview (~30 min): examined the lived experience of logging, whether the pause affected behavior, what patterns participants noticed, and how their interpretation of over-reliance and “think-first” habits evolved.

Data types collected:

- Quantitative: repeated session-level numeric ratings (confidence, satisfaction, correctness confidence, efficiency confidence, comfort sharing, ownership) + time spent.

- Qualitative: task type, importance, and reasons for LLM use plus semi-structured interview narratives before/after the diary period.

2) Participant Recruitment

Recruitment approach: Participants were recruited via a short screener targeting people who already use chatbots regularly.

Inclusion criteria (from screener):

- Uses chatbots at least 1-4 times per week (people who “Don’t use at all” were disqualified).

- Willing to log every chatbot session for 5 consecutive days (~5 min/day).

- Self-reported reliance on chatbots captured on a 1–10 scale (10 = extremely reliant).

Demographics:

3) Key Research Questions

Grounded in the project goal (supporting independent thinking before LLM use), the baseline study targeted four core questions:

- When and why do people initiate an LLM session?

Captured via: task type, task importance, and “why did you decide to use a chatbot?” (diary), plus walkthrough of most recent use (pre-interview).

2. How does multi-dimensional confidence relate to “LLM-first” behavior?

Captured via: pre-use confidence rating (diary) and interview prompts unpacking confidence into correctness, quality, reasoning, efficiency, social comfort, and ownership (pre- + post-interview).

3. What does “over-reliance” mean to participants in practice, especially in terms of outsourcing thinking/judgment?

Captured via: pre-interview reflection on over-reliance + post-interview reassessment after the diary period.

4. Does adding a brief pause disrupt habitual LLM use and trigger “think-first” moments? If so, when does it work or fail to register?

Captured via: post-interview questions on whether the logging pause caused hesitation/reframing, which task types were affected, and what barriers make pausing hard (e.g., time pressure, fatigue, discomfort with ambiguity).

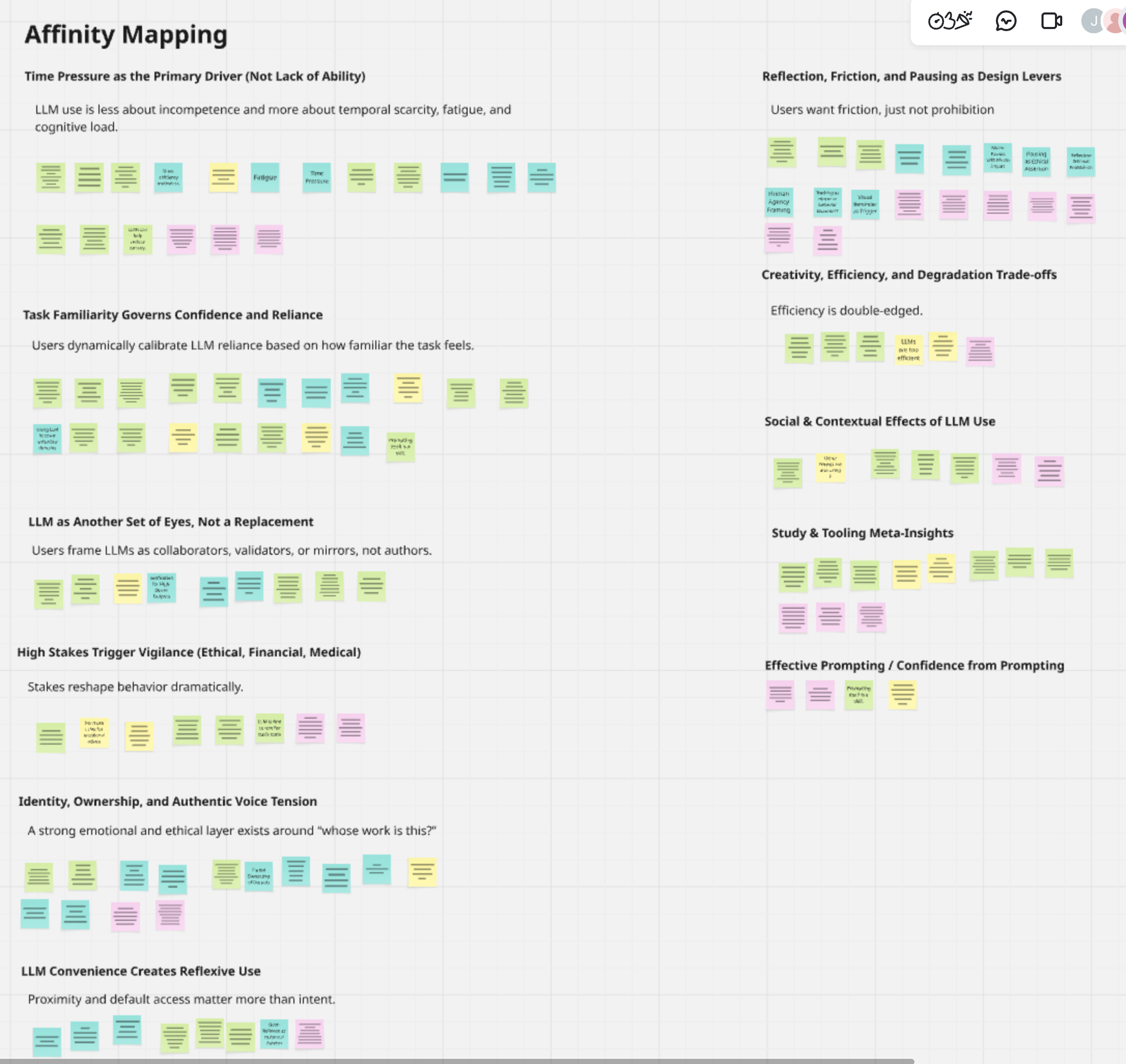

4) Affinity Map

For more detailed affinity map, please visit here.

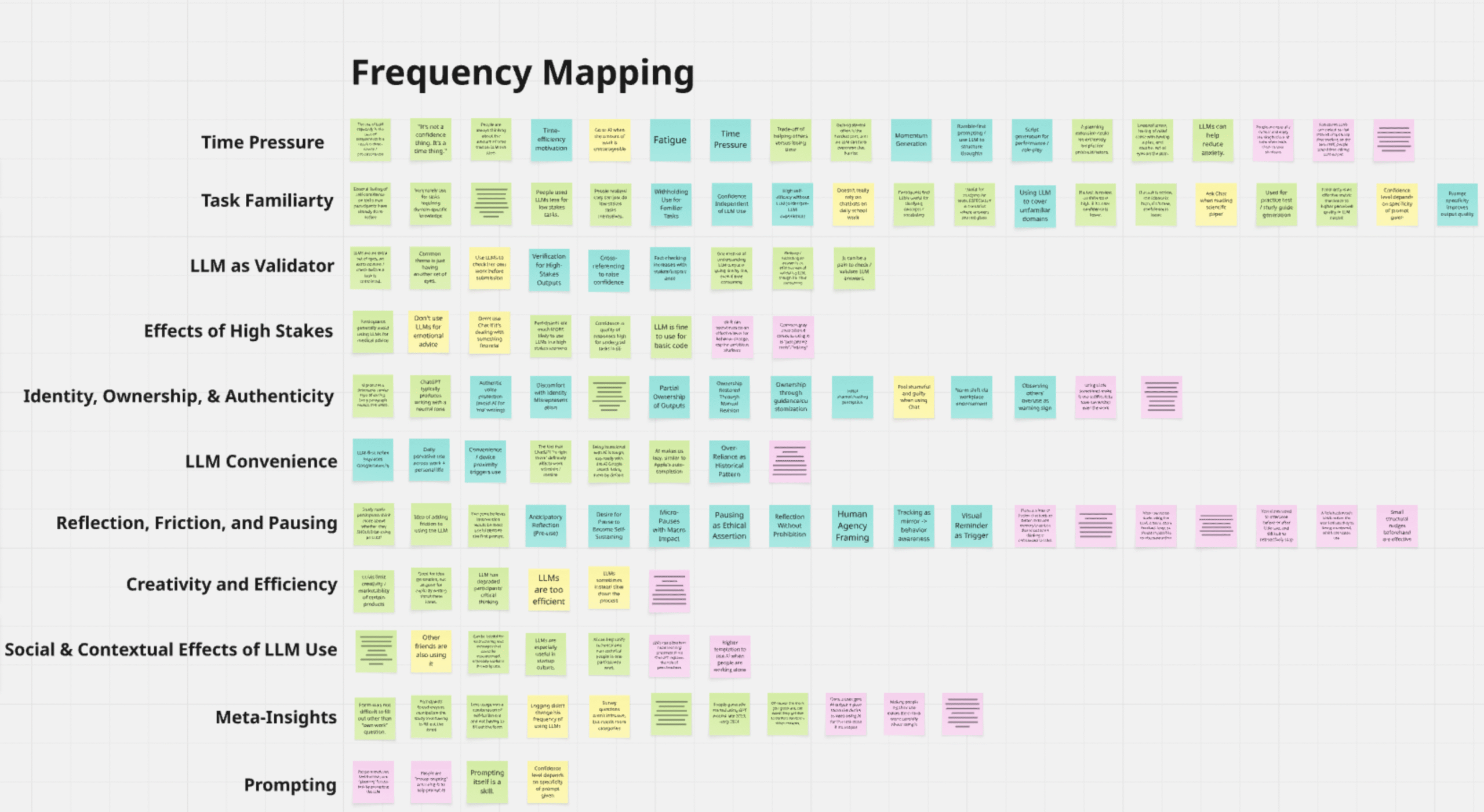

5) Frequency Map

For more detailed frequency map, please visit here.

Grounded Theory Report (Link)

Grounded Theory 1: People’s reliance on LLMs is best explained by time scarcity and cognitive load, rather than by low confidence in ability or lack of skill.

Subtheory: LLM use emerges as a response to temporal compression.

- Bella states that when she realizes she has a very limited window (sometimes as little as 30min), she shifts her strategy toward whatever helps her finish fastest. She explicitly frames ChatGPT as the tool that lets her “do it more efficiently,” meaning the time constraint itself triggers the decision to use an LLM.

- Question 1: How much time does ChatGPT save compared to more traditional studying methods?

- Question 2: Is this additional time saved leading to productivity? Or creating a further procrastination loop?

- Travis states that he keeps the diary-logging interface “open all the time,” and that constant visibility acts like an immediate, proximity-based cue to reflect on his choice. He describes it as a “visual reminder,” which makes the decision feel more immediate and harder to ignore in the moment. When making the choice, he explicitly weighs whether it’s “worth it” by comparing the time saved using an LLM versus “the 20 minutes” he’d spend doing it himself.

- Question: How does time pressure affect the norms of independent work?

Subtheory: Convenience and proximity amplify time-based decisions.

- Andrea, a college student studying EE, states that people make time-based choices in favor of ChatGPT when it’s the most convenient option, because its speed and low effort reduce the “friction” of getting an answer.

- Jonathan states that LLM use can be almost automatic because the access pathway is frictionless. That default behavior shows proximity in practice. He claims that the LLM is embedded in his browsing flow, so it’s always within reach.

- Quote: “My default is I go into Safari, open a new tab, press C, and enter, and then immediately … an infinite … well of knowledge just appears in front of you.”

- Question: What happens when time pressure is reduced, but convenience remains high?

- Quote: “My default is I go into Safari, open a new tab, press C, and enter, and then immediately … an infinite … well of knowledge just appears in front of you.”

Grounded Theory 2: People conceptualize LLMs as collaborative checks or mirrors, rather than authoritative problem-solvers.

Subtheory: Validation, reassurance, and momentum are central functions.

- Justin Qin states that he uses the LLM less as an “authority” and more as a collaborative check, which for him is an extra perspective that helps him feel confident he’s not missing something. He explicitly ties the emotional benefit to relief and reduced stress, because the LLM helps him feel he has a solid plan rather than being alone with uncertainty.

- Question: Even beyond the context of an LLM, what emotions do people feel when their work / efforts are validated?

- Travis states that the LLM functions like a confidence mirror, where he uses it to confirm he’s on the right path, not just to output an answer. He describes reassurance as a core value (“I know I’m on track”), which highlights the LLM’s role in stabilizing decision-making and reducing hesitation. He also names “momentum” directly, suggesting the tool helps him keep moving rather than getting stuck or second-guessing.

- Quote: “there’s a strange sense of like being supported…” and “…momentum is a big one…”

- Question: How consistent/stable is the extra set of eyes framing across different task domains…?

- Quote: “there’s a strange sense of like being supported…” and “…momentum is a big one…”

Subtheory: LLMs are effective at overcoming initiation barriers.

- Bella states that the hardest part of work is not the work itself, but initiating. She describes that once she starts one question, the task feels psychologically lighter, which shows the barrier is front-loaded at the beginning. She also frames that LLMs make initiation more feasible since it compresses the perceived effort/time required to begin.

- Question: What intervention(s) could make the process of getting started on a given task easier for high-school and college students?

- Michael states that opening ChatGPT is an easy default action that bypasses the cost of deciding how to approach a question. He believes that LLM lowers the activation energy of beginning: instead of planning, searching, or wrestling with uncertainty, he can immediately offload the first move to the tool.

- Question: How does the initiation barrier differ across types of tasks (e.g., creative tasks vs. non-creative tasks)

Grounded Theory 3: Participants experience persistent tension between the efficiency benefits of LLMs and concerns about authorship and self-representation.

Subtheory: Writing tasks heighten concerns about identity and ownership

- Bella states that writing is the category where authorship matters the most, so AI-generated prose feels identity-threatening rather than helpful. She describes AI writing as stylistically uniform and “obviously AI,” which makes it feel detached from a real person’s voice. She also notes that the reasoning in AI argumentative writing can feel “off,” which further undermines her willingness to claim it as her own work. In other words, writing tasks heighten her concern that the output won’t represent her thinking or self-presentation.

- Quote: “I will never use LLMs for writing at all. It just seems like all these topics [in the essay] don’t connect and it has the same style of writing that’s so obviously AI.”

- Question: Can humans typically detect whether writing is AI-generated or human-created on a consistent basis? Can AI detect this?

- Quote: “I will never use LLMs for writing at all. It just seems like all these topics [in the essay] don’t connect and it has the same style of writing that’s so obviously AI.”

- Travis states that even when LLMs make writing faster, they introduce a constant negotiation over “how much of this is me,” especially when the phrasing sounds generic or “robotic.” He distinguishes between outputs that merely reorganize his own text (which feel more representational) and outputs that introduce new AI-authored sentences (which feel less like his work). He explicitly links revision to ownership, saying that adding his voice increases the sense that the final product is truly his.

- Question: How do perceptions of “own voice” differ across domains (e.g., technical vs. personal)?

Subtheory: People at times feel morally wrong for using LLMs, but will fall behind others if they don’t.

- Jordan states that while LLM was originally perceived as “bad” or equivalent to cheating, their perspective shifted once they experienced how it can increase work productivity. They explain that his colleagues and boss shared that LLM enables them to handle multiple projects and increase productivity, increasing the value for the company. As a result, Jordan describes a transition from moral hesitation (“maybe I shouldn’t use this”) to seeing LLM as a productivity tool.

- Question: When do moral emotions (e.g., feeling that LLM use is cheating) successfully limit over-reliance and when are they overriden by time pressure or task stakes?

Grounded Theory 4: People’s confidence is mediated by task familiarity, as well as the level of stakes on the task.

Subtheory: Familiar tasks decrease reliance and increase skepticism.

- Travis states that when a task is routine and familiar, his confidence increases. That higher confidence implies lower reliance: the tool becomes optional support rather than a primary driver of progress. In contrast, for new projects he knows less about, his confidence drops, which pushes him toward more tool use to bridge knowledge gaps.

- Justin Qin states that familiarity is what lets him judge whether an LLM output is correct, because he can compare it to what he already understands and follow the logic. He claims that when the task is familiar, he can confidently catch errors. However, when familiarity is low, confidence becomes harder to justify, and reliance tends to rise since he has fewer internal checkpoints.

- Question: Can perceived familiarity be utilized to reduce over-reliance on LLMs?

Subtheory: If a task is viewed as lower stakes, it is generally easier to avoid LLM usage than if it were higher stakes.

- Andrea states that he often uses LLMs when the tasks are application-related, where there isn’t that much variability. In contrast, when the task is personal learning or skill-building, he experiences much less cost in slowing down. Andrea claims that this makes low-stakes or intrinsically motivated work easier to do without LLM support, while high-stakes outputs push her toward LLM use.

- Question: How can systems surface task stakes as a decision cue?

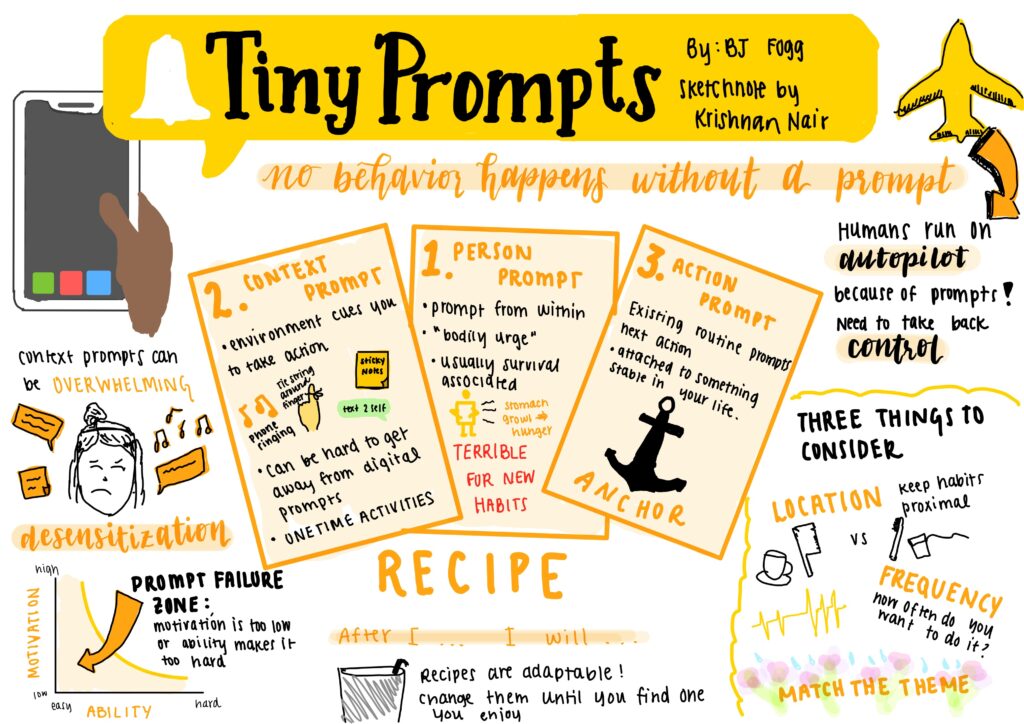

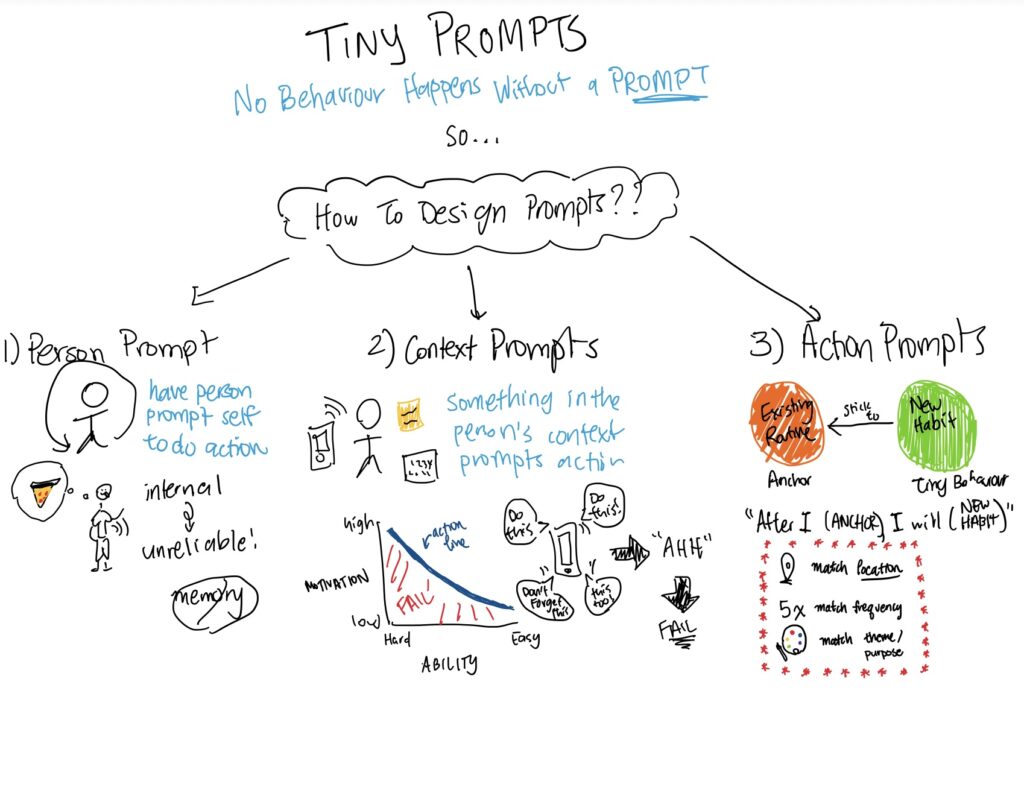

Grounded Theory 5: Participants think that interventions are most valuable before the first prompting, only with preserved agency.

Subtheory: Pausing triggers reflection.

- Travis states that a light interruption right before prompting creates the mental space to reflect on whether LLM use is actually necessary. He said that the pause only needs to be a few seconds, and it will often trigger a check for LLM usage. Importantly, Travis claims that the intervention (the pause) is reflective instead of restrictive.

- Michael implies that the default workflow is frictionless: he can open ChatGPT “easily” without thinking. However, he argues an intervention should create a “mental barrier” that forces a quick pre-use check, asking questions such as “should I actually use ChatGPT for this?” That barrier is framed as prompting reconsideration rather than forbidding use, which preserves user agency while still slowing down autopilot behavior.

- Question: How can pauses be personalized to task types, familiarity, and stakes?

Subtheory: Intervention during or after LLM usage would be ineffective, largely due to an already established feedback loop.

- Justin Qin believes that the intervention would be most useful before engagement with an LLM, inferring that the “end” of an LLM interaction is already past the point where behavior can be meaningfully redirected, because the user has already committed. He describes LLM usage as entering a momentum loop (such as reels) where opening the session initiates a self-reinforcing flow. Finally, he believes that intervention is most plausible before engagement, since during/after the feedback loop has already taken over.

- Quote: “Just cause I feel like once that’s open, it’s sort of like Instagram Reels. Once that’s going, it’s going.”

- Question: Is there any way to disrupt / break the momentum loop?

- Quote: “Just cause I feel like once that’s open, it’s sort of like Instagram Reels. Once that’s going, it’s going.”

- Dr. Aleeta states that the only workable intervention timing is before she begins composing the prompt. Once she’s already interacting, the intervention has already missed its leverage point. In practice, this means an intervention after the first response would be too late, because it interrupts after she has already invested attention and intent into the LLM workflow.

- Question: What is the best way of taking advantage of the leverage point and keeping people’s interest BEFORE they enter the LLM workflow process?

Grounded Theory 6: Prompting as a learned skill that shapes both output quality and personal confidence.

Subtheory: Specificity of prompt restores agency.

- Michael discusses the importance of having a strong, specific prompt and providing appropriate context for the chatbot to be able to produce a good output. He explains that he will often “metaprompt”, where he’ll “”ask AI like the best ways to frame something or even I might use other AIs to like helped me, I like, I guess prompt engineer for other [AI’s]”, demonstrating how he carefully crafts prompts and must properly learn and understand what the project requirements and goals of the task are in order to efficiently and properly complete them. He explains that he would also try to create an “outline that I can paste into ChatGPT” to give it a more structured understanding of the task and therefore to produce a stronger result. All in all, this demonstrates a greater role of critical thinking in the prompt-making process.

- Question: How does prompting literacy relate to confidence and over-reliance?

- Dr. Aleeta Bell states “I pay special attention to my prompt. Like, how do I write things? you know, how would I state this to get the best quality answer out of the LLM?”, once again demonstrating the importance of the individual agency that comes with making a prompt as specific as possible and maximizing its output. Her main focus is on learning to write “a better quality, more concise prompt” every time she uses an LLM. During this process, she has to figure out the best and most useful things to put in the context window and understand the scope and nature of the problem at hand and the output she wants to obtain, demonstrating how individual specific prompting restores agency.

- Question: How does the process of prompting an LLM add more human input and complexity to the process?

Subtheory: Prompting skill frames LLMs as tools, rather than authorities.

- Bella explains the importance of working with chatbots as an iterative process with continued reinforcement around the prompt and discussion, not as a penultimate and final call on what the solution/result to a problem or task should be. She states that she will “check if like my steps align with the AI chatbot steps, but if they don’t, I will like continue doing the question and ask it like tons of follow-up questions like to go more in depth to like this step or this step or like explain the overarching topic in general.” This demonstrates how when there are refinements that need to made to what the user is inputting into the chatbot, it frames the LLM more as a tool. She states that she “tend[s] to upload… full powerpoints of what we learned in class and then ask the chatbot to generate it like from this information because otherwise it’ll be too general.”, reflecting a continued process of rethinking and optimizing her tool use rather than simply outsourcing everything to the LLM.

- Travis frames the LLM as an instrument that helps him with his goal, instead of an authority that owns the decision or dictates the outcome. This implies that skillful prompting is less about asking an expert, but more about operating a tool well to produce the desired result.

- Question: How effective is prompting in restoring agency back to the user and helping them learn more than they otherwise would have?

System Models

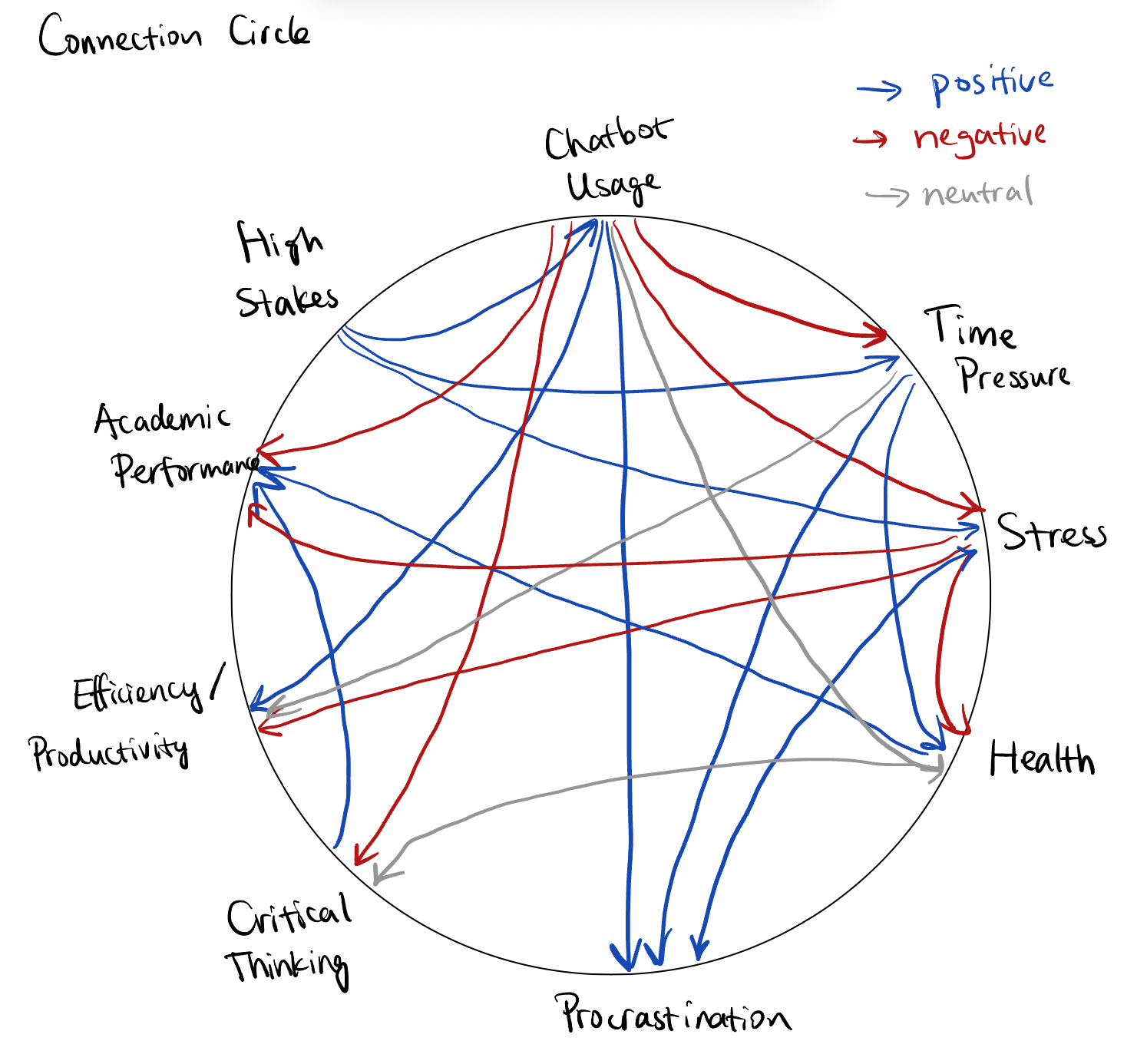

- Connectivity Circle

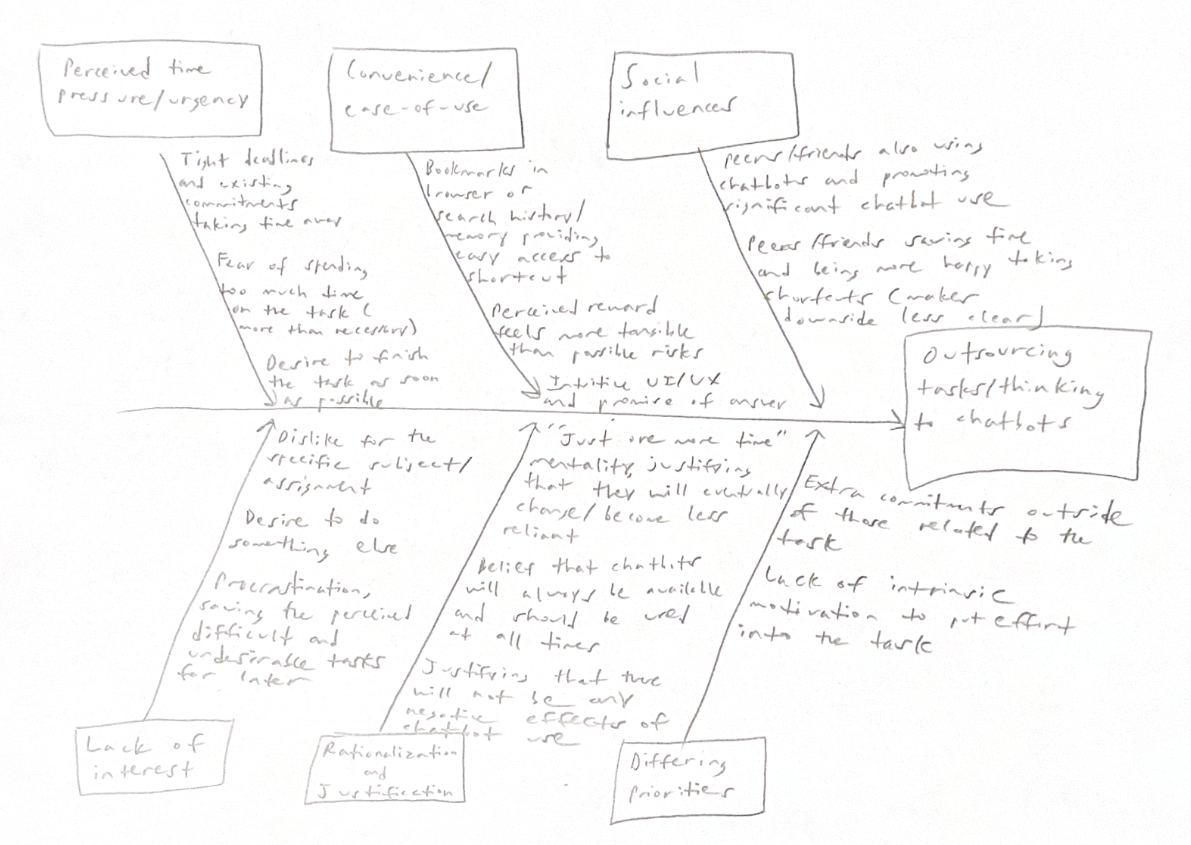

2. Fishbone Diagram

Secondary Research (Link)

Literature Review

Prior research has raised increasing concern that uncritical reliance on LLMs can undermine human reasoning, autonomy, and learning. Existing HCI interventions primarily adopt reactive strategies, such as uncertainty highlighting, disclaimers, explanations, or interface frictions, that regulate user trust after or during exposure to LLM outputs (Modulating Language Model Experiences through Frictions,; Better Slow than Sorry). While effective at reducing blind acceptance, these approaches largely assume that users have already deferred to the model. Complementary evidence from behavioral intervention and harm-reduction literatures emphasizes that overuse of digital systems requires empirically grounded design interventions rather than purely therapeutic responses (Smartphone Addiction in Youth). More recent cognitive and neurophysiological studies further show that direct LLM reliance can accumulate “cognitive debt,” reducing memory retention, sense of ownership, and strategic integration, whereas workflows that require users to generate ideas independently before using LLMs lead to higher engagement and better outcomes (Your Brain on ChatGPT). Together, this literature reveals a clear gap: prior systems focus on moderating reliance after LLM engagement, leaving underexplored the design of pre-engagement interventions that promote independent thinking and position LLMs as tools for refinement rather than cognitive substitutes.

Comparative Research

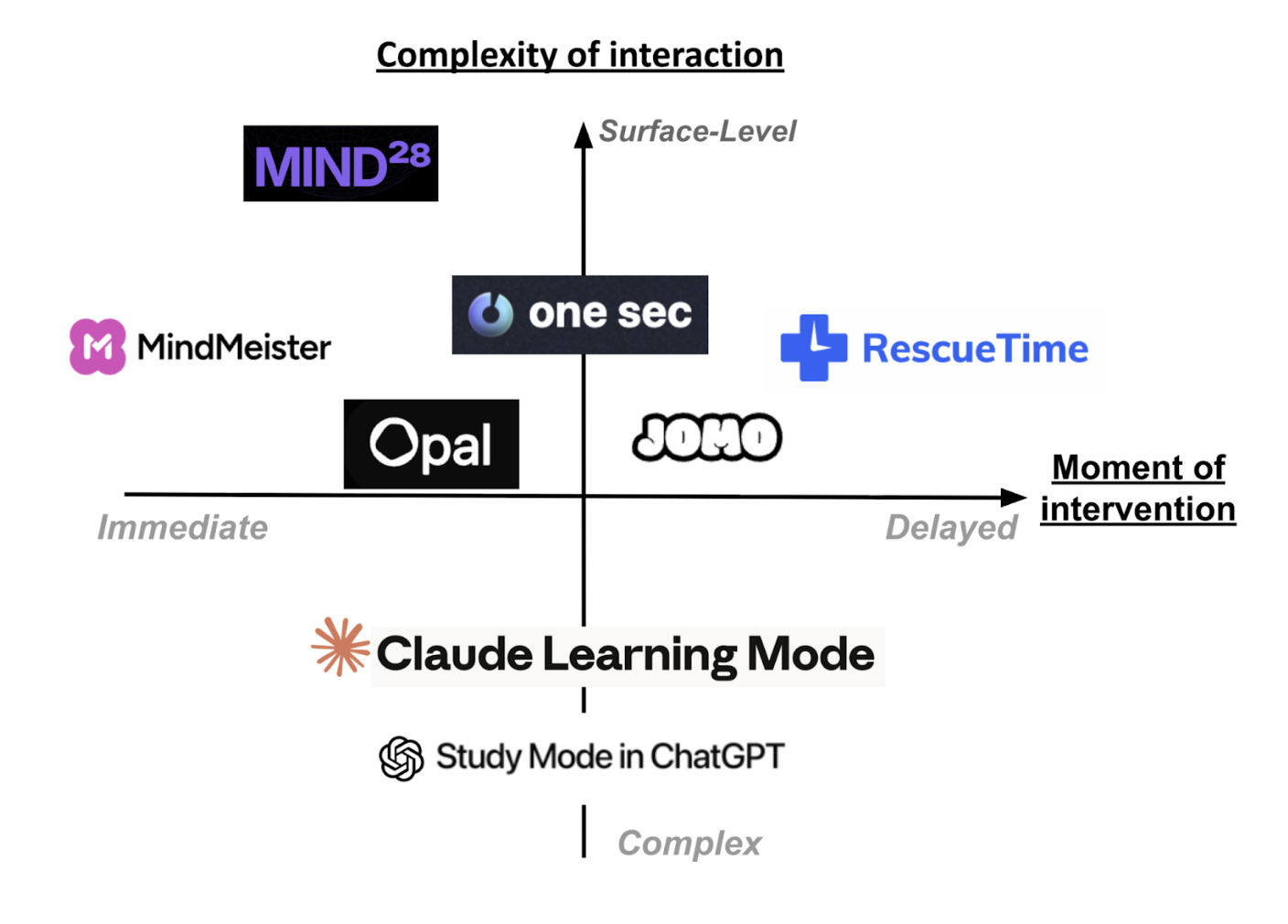

Existing tools for digital self-regulation largely focus on reducing time spent on technologies through blocking, friction, or post-hoc analytics (e.g., One Sec, ScreenZen, Jomo, RescueTime), but do not support improving the quality of engagement or users’ independent thinking. In contrast, in-LLM learning modes (e.g., ChatGPT Study Mode, Claude Learning Mode) promote reasoning only after users have already deferred cognition to the model, reinforcing LLM-first behavior. Early pre-use interventions such as Mind28 begin to address this gap by enforcing a brief “think-first” phase, but rely heavily on user motivation. Together, this work reveals a clear opportunity for systems that intervene immediately before LLM prompting, using lightweight, structured cognitive support to activate independent reasoning without blocking AI use.

We want to combine some of the ad-blocking competitors that we’ve seen (ScreenZen / 1Sec) with some of the intervention competitors that we’ve seen (MindMeister) in order to create a Google Chrome extension which really encourages users who may find themselves almost defaulting to LLMs for certain tasks to engage in more critical thinking. After feedback that we have received in our post-study interviews, we ideally want our intervention to be somewhere in the bottom-left quadrant of our chart– an intervention that occurs immediately (before prompting the LLM with your question) and an intervention that is leaning towards being complex, but not overwhelming (allowing for customization and potential different interruptions we can explore based on ideas that other competitors had).

The majority of the other tools that involve post-activity tracking and delayed interventions primarily involve understanding the analytics of people’s usage and screen time and then imposing certain quantitative amounts of friction (screens, limits, blocking, etc.) to try to correct for and adjust for that behavior. The main problem with these types of interventions is that they do not try to improve the time that the user spends using those kinds of tools, they only try to reduce the time that the user spends on them. For example, tools like Jomo and RescueTime do not make the user more effective at using LLM tools and train them to get better at applying new technologies, instead they are trying to analyze their behavior after they use the tools and then set interventions after that analysis.

Mind28 represents an important first step toward pre-LLM interventions, but its simplicity places the burden of reflection almost entirely on the user. Our work builds on this foundation by exploring how carefully designed, customizable interruptions can support thinking without forcing users. By situating the intervention immediately before LLM prompting and enriching it with structured cognitive support, we aim to reduce reliance on user willpower and instead make critical thinking the path of least resistance.

X-Axis: Moment of Intervention (This is the amount of time or the relative time the intervention occurs after opening an app. For instance, if you are immediately prompted with the intervention / interruption, the intervention will be low on the X-axis. If there is a delay of several minutes, then the intervention will be high on the X-axis/

Y-Axis: Complexity (This refers to how complicated the app may be. This can refer to the amount of customization, the amount of onboarding, the number of features, where the app is solely just a chrome extension vs a chrome extension + mobile app + browser, etc.)

Persona & Journey Maps

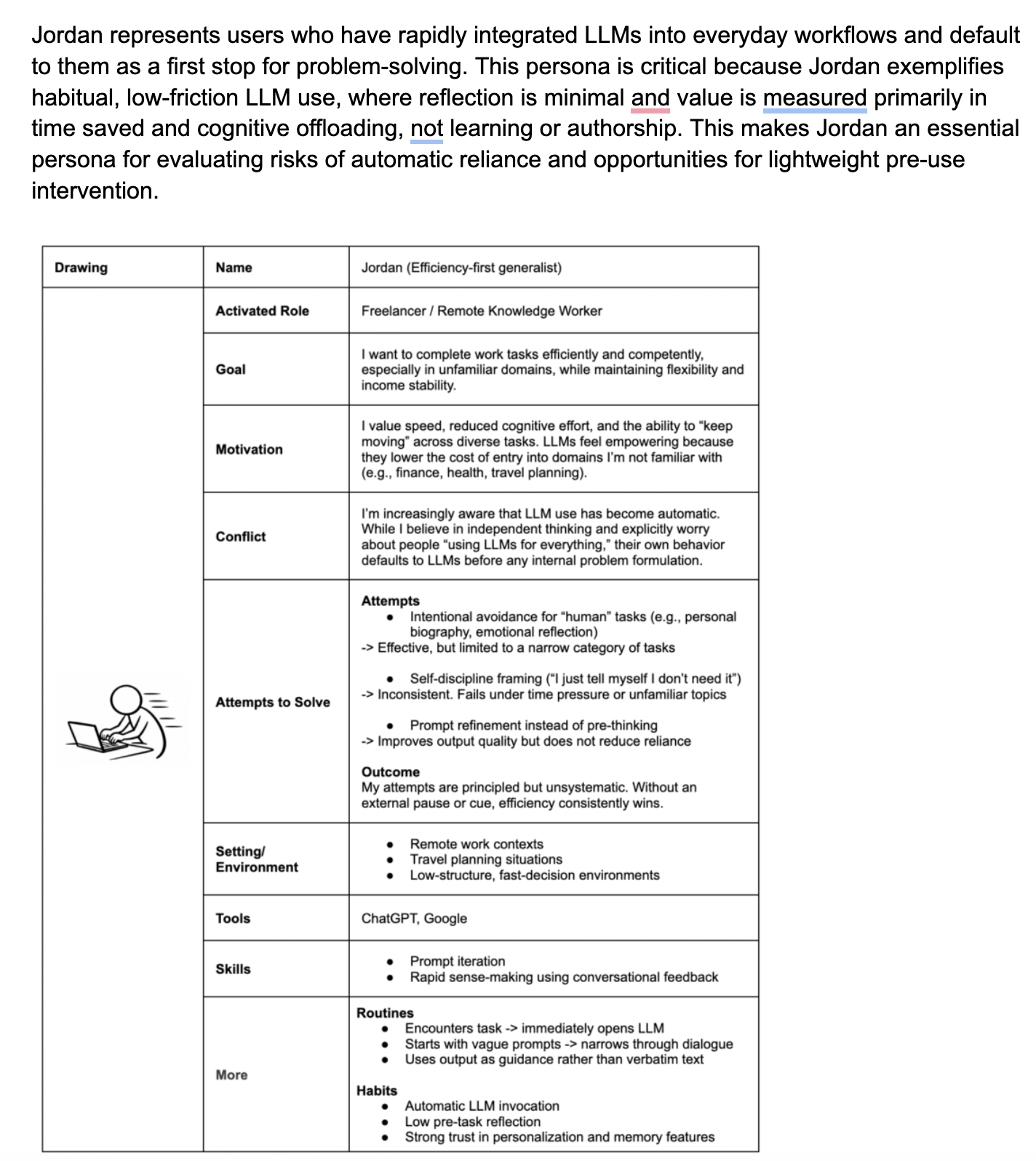

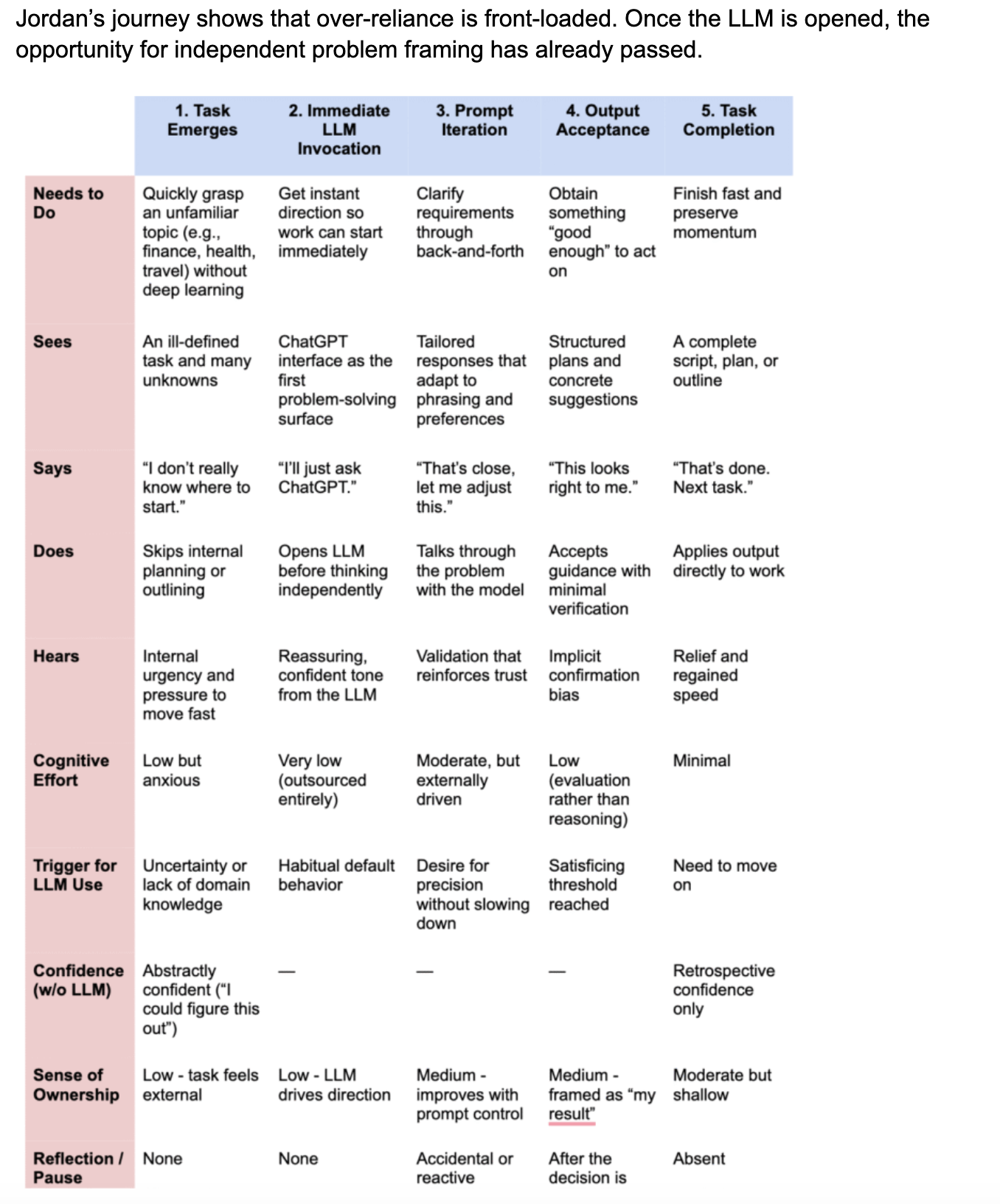

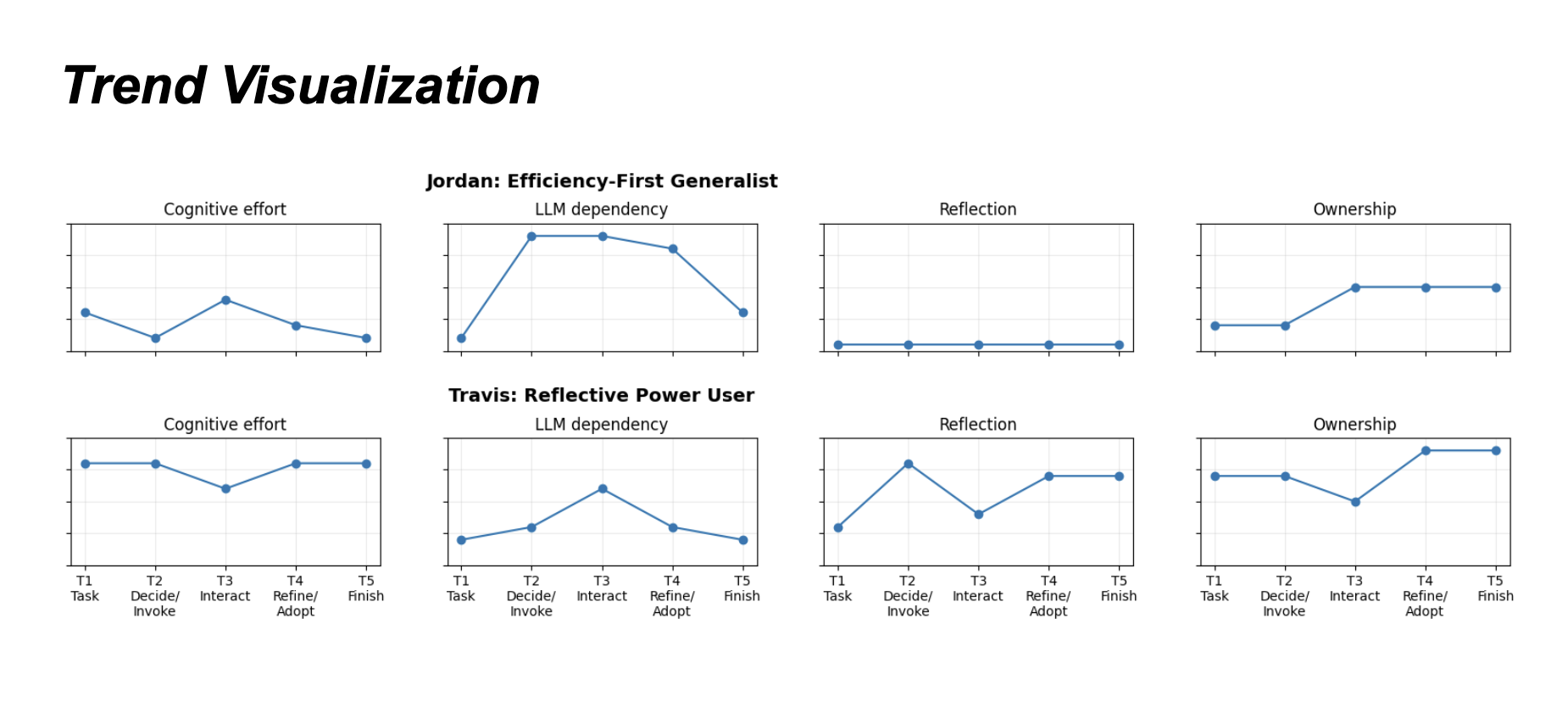

Persona 1 – Jordan (Efficiency-first generalist)

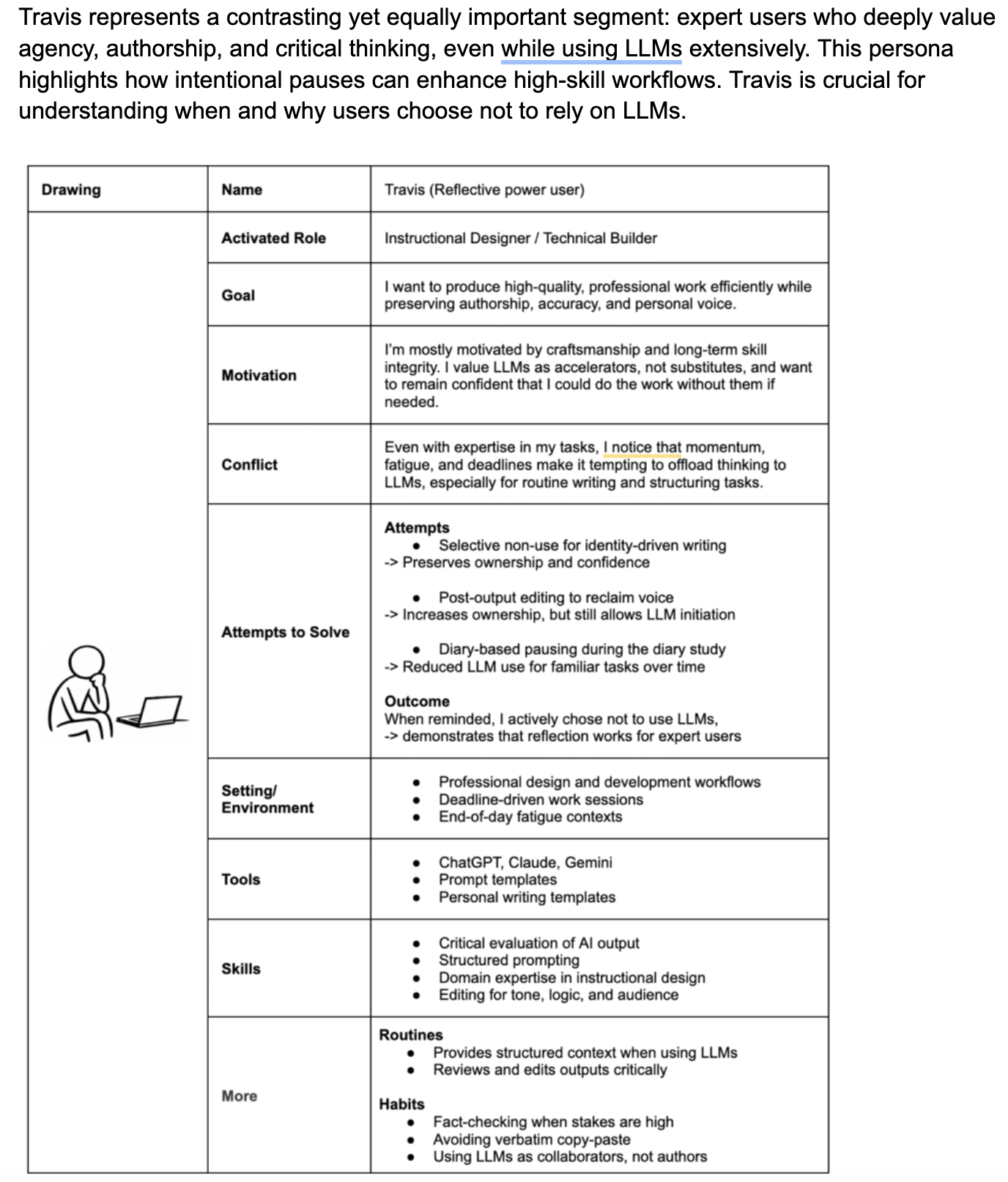

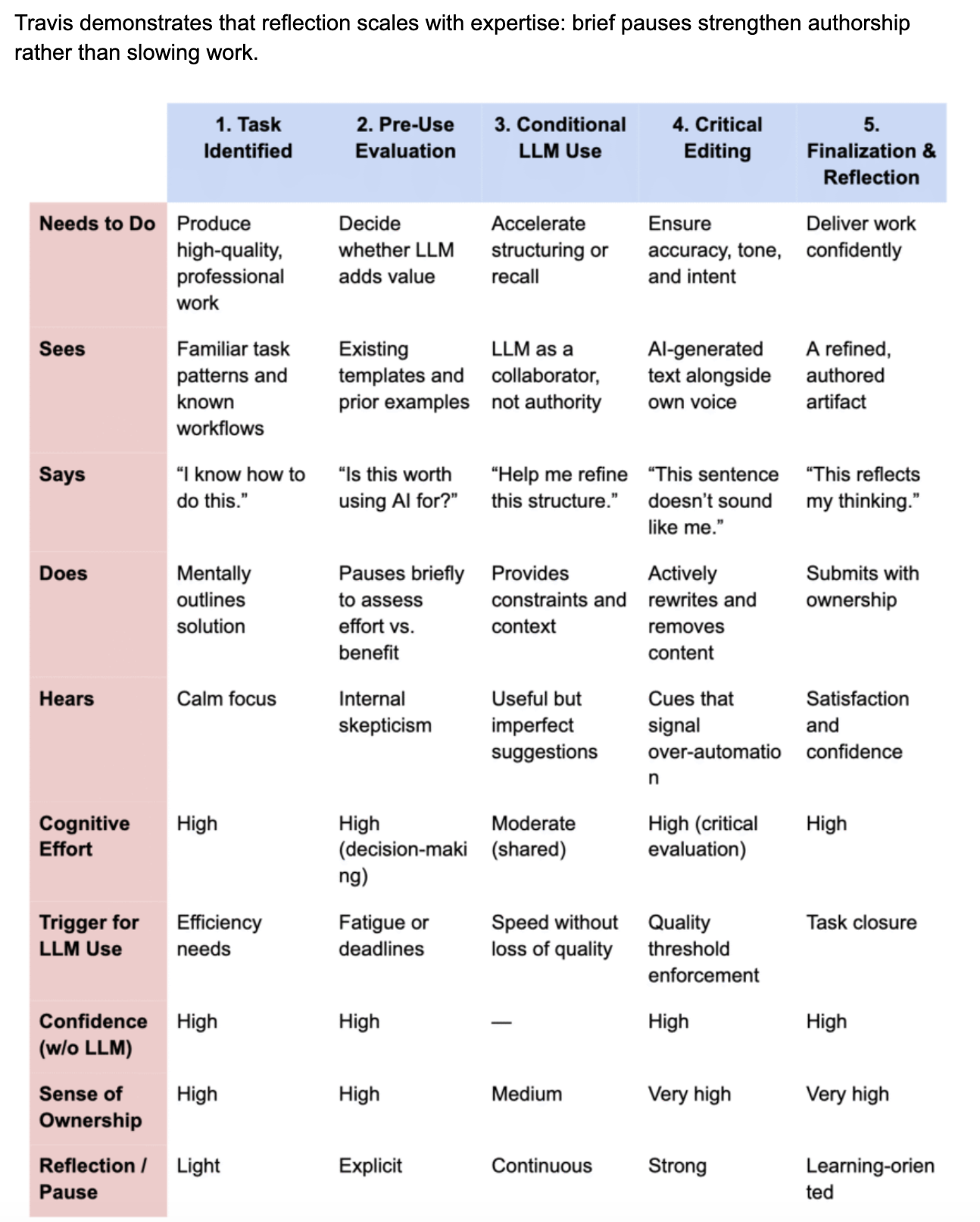

Persona 2 – Travis (Reflective Power User)

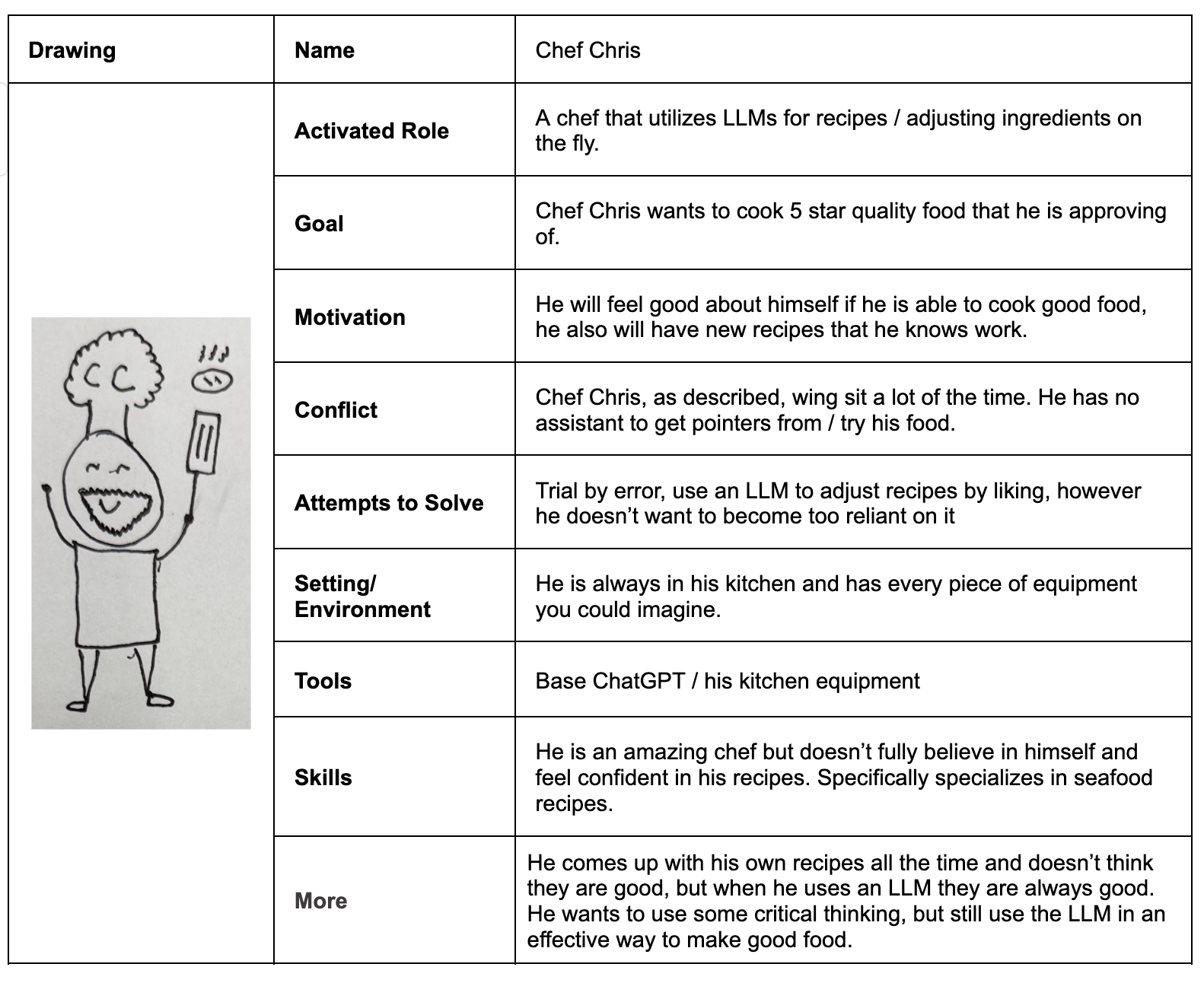

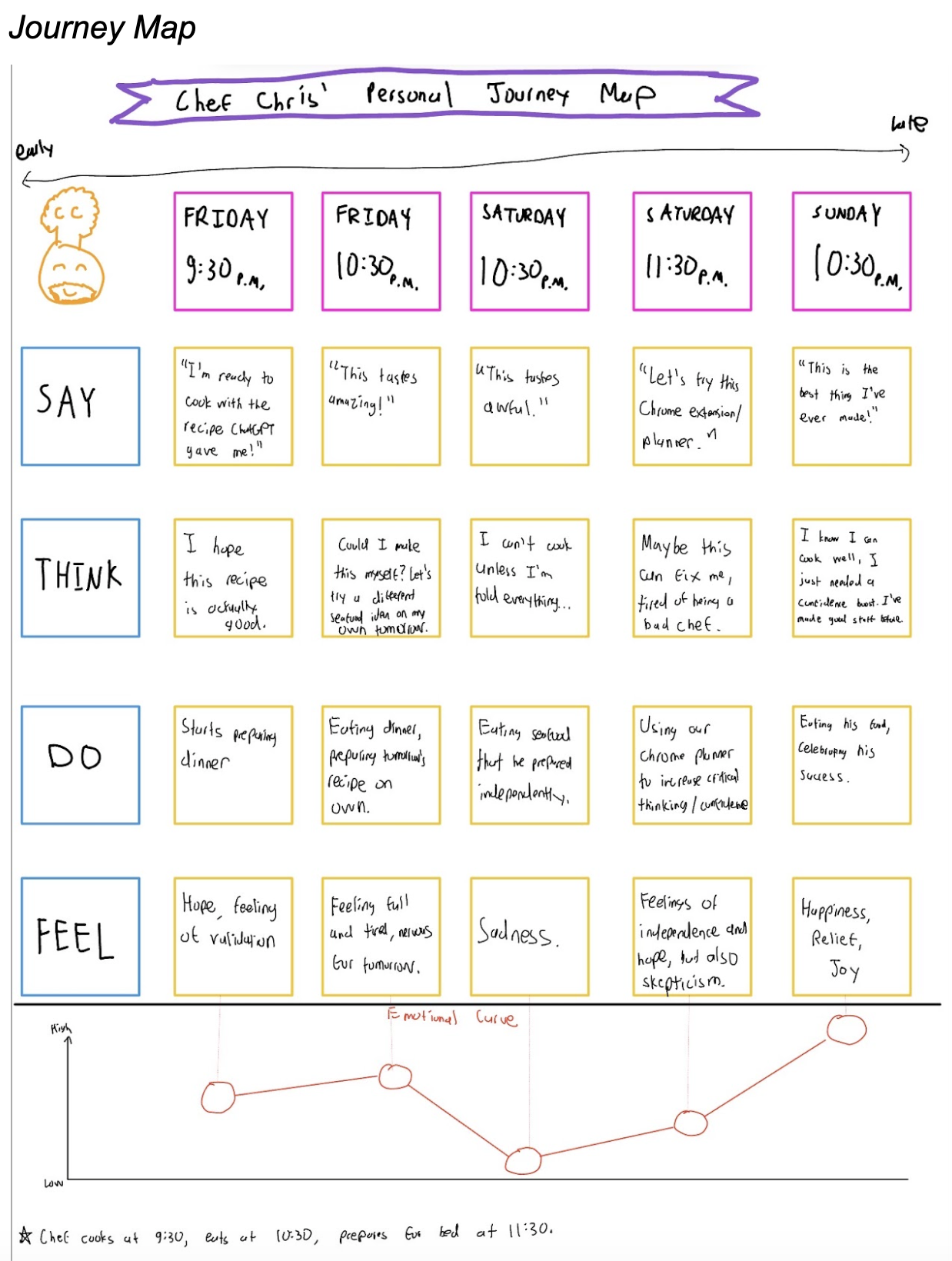

Persona 3 – Chris (Chef)

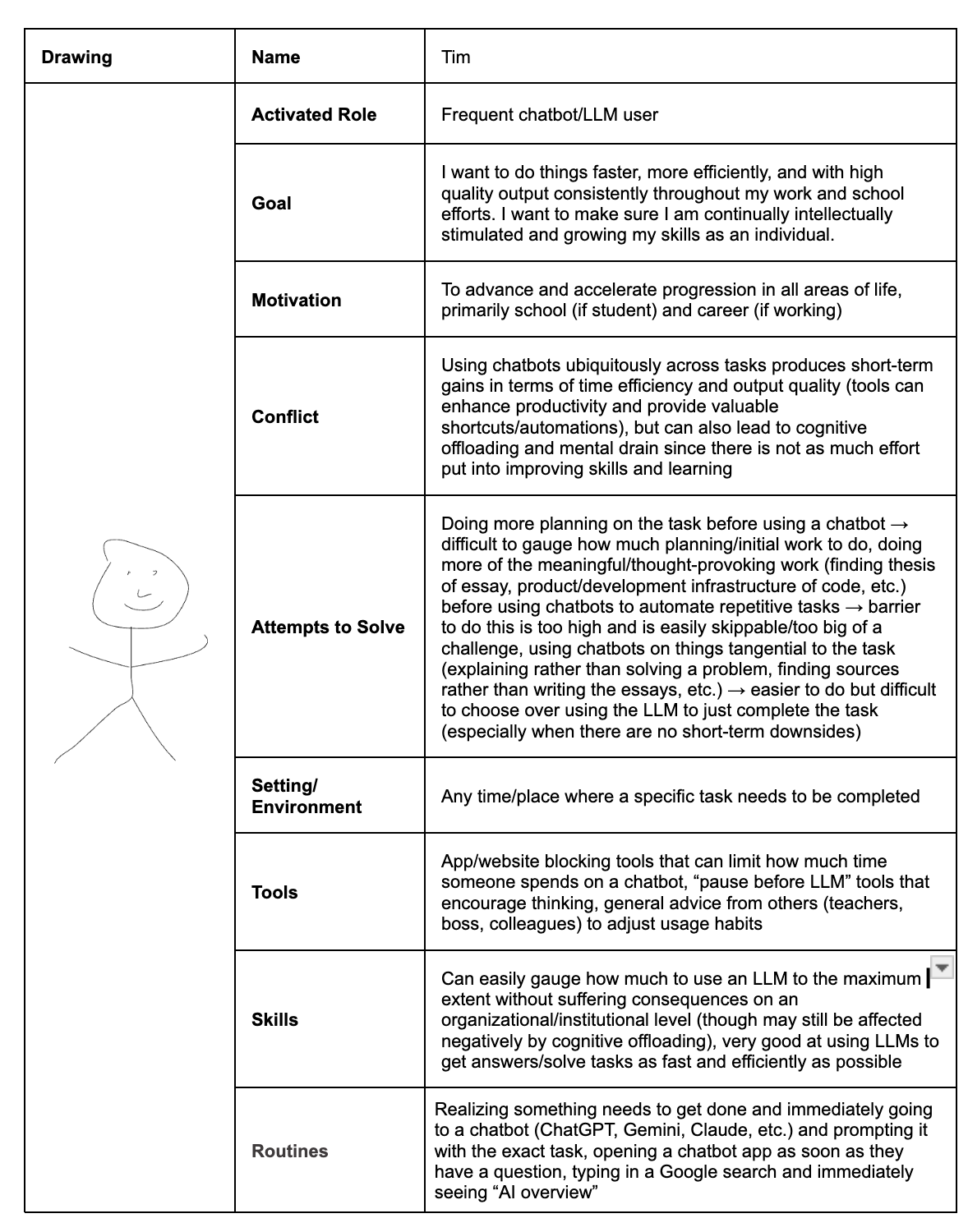

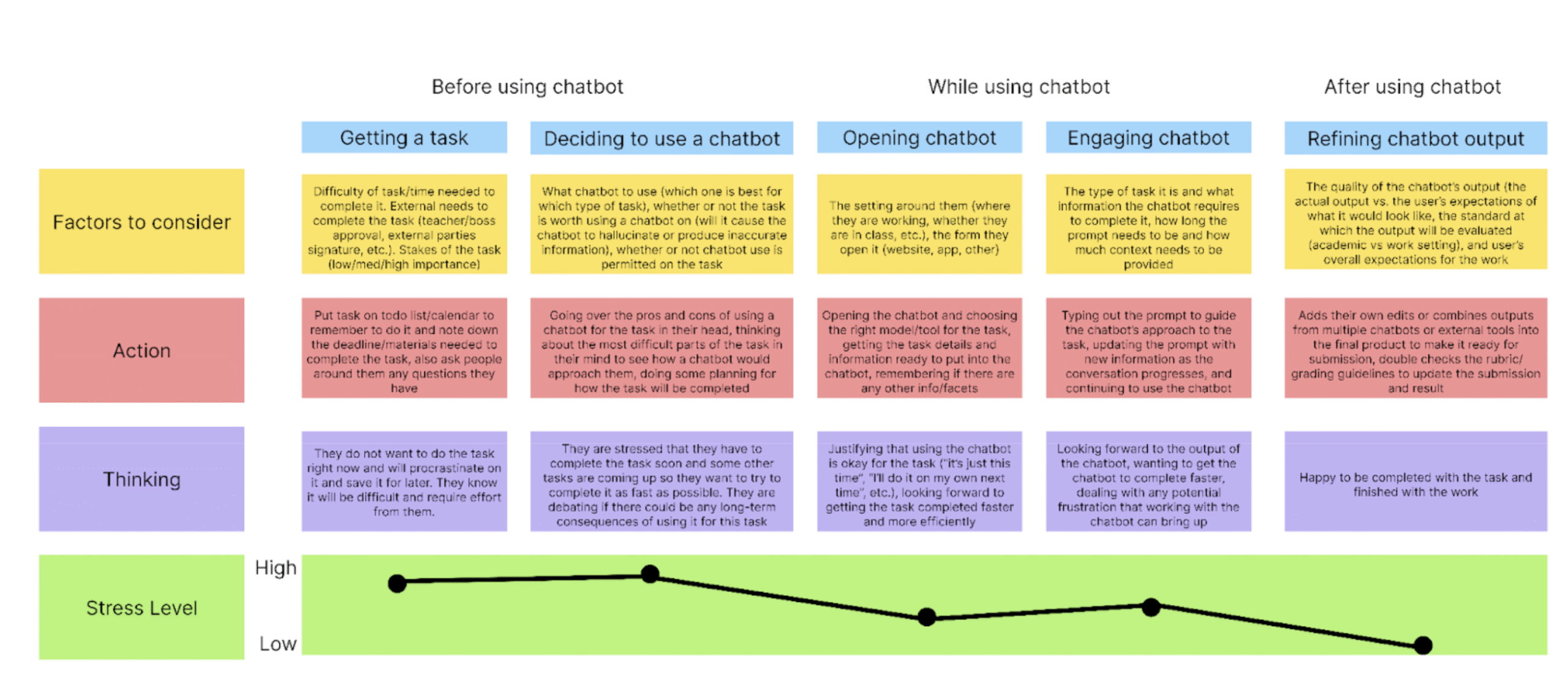

Persona 4 – Tim (Frequent LLM user)

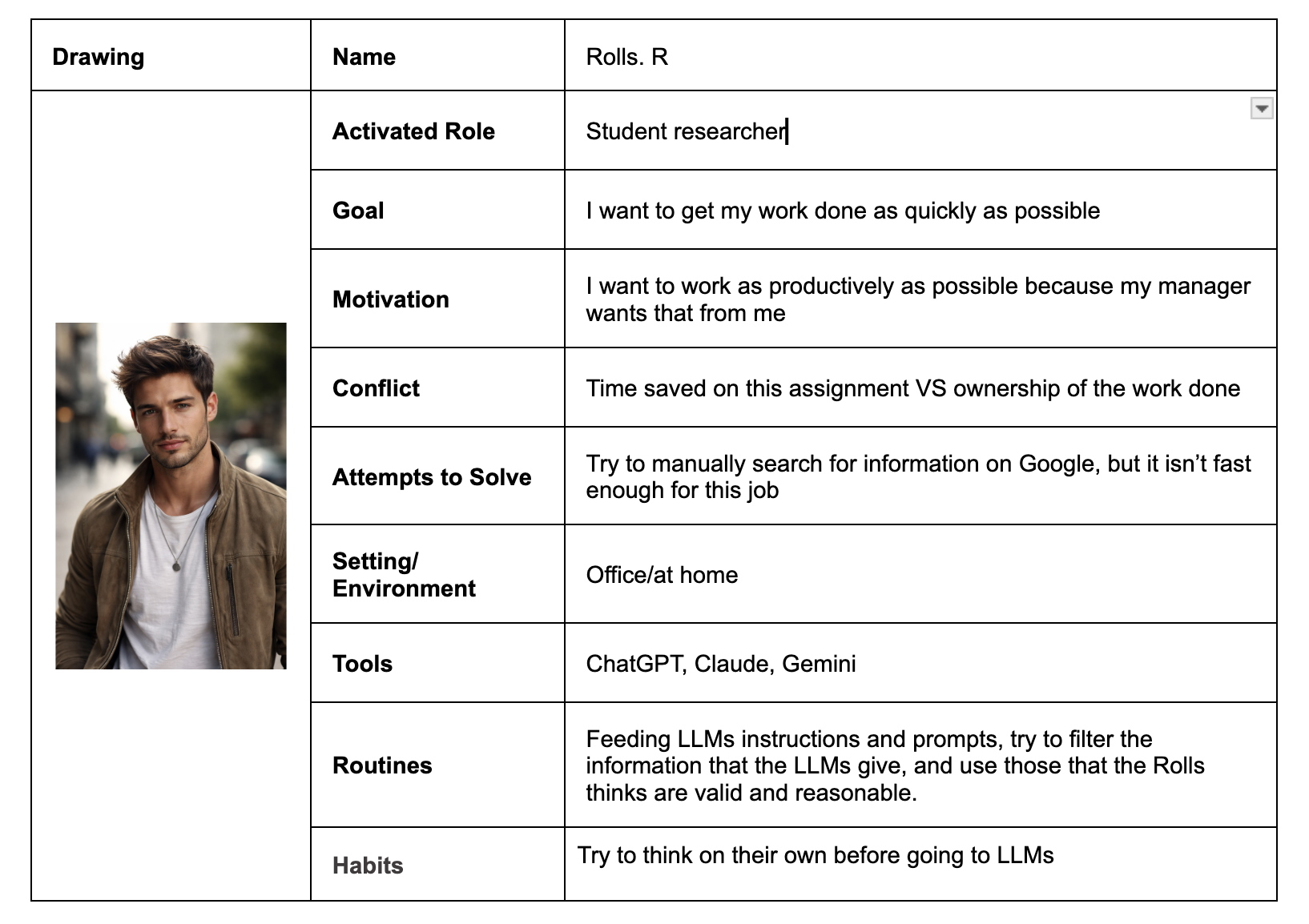

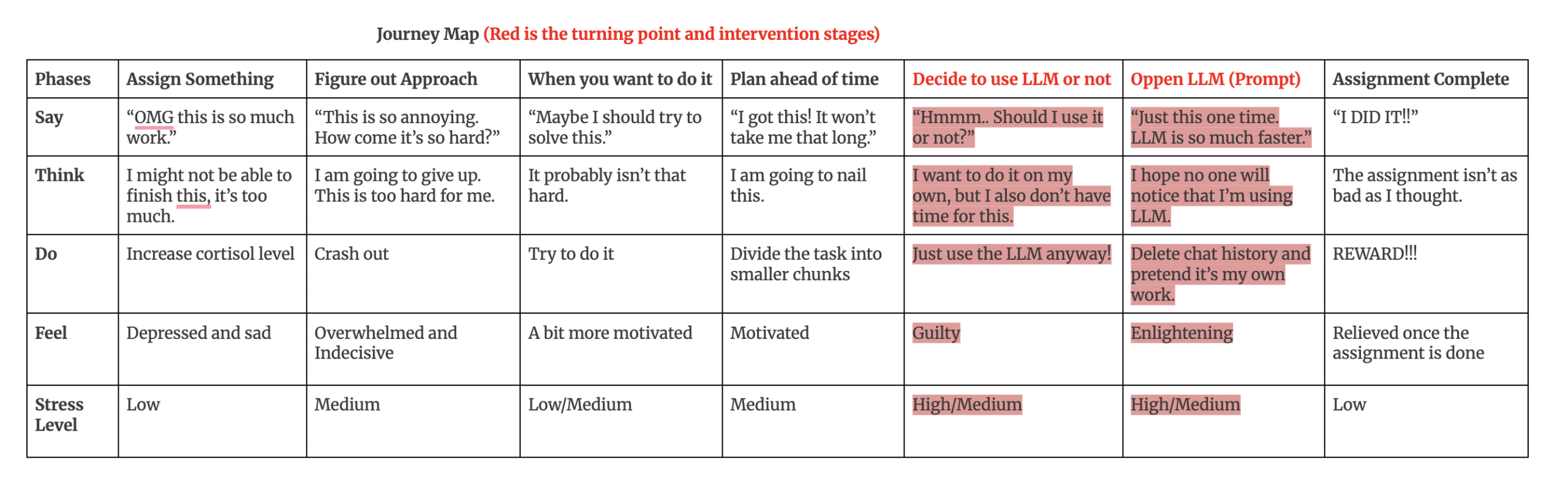

Persona 5 – Rolls (Student Researcher)