Midpoint Writeup

Problem Domain & Motivation

How might we help our peers reduce their screen time during the early morning hours?

Upon waking up, many people immediately turn to their phones to check messages, see emails and scroll through social media or news feeds. While technology has benefits, this heavy use in the morning can be overwhelming and distracting, overall impacting productivity and wellbeing throughout the day.

Inspired by our and our peers’ Measuring Me’s, we set out to design a solution that encourages users to reduce their technology use in the morning, focused specifically on phone usage in bed. We aim to reduce screen time while still providing users with the necessary tools and information to start their day effectively.

Baseline Study

Our target audience is college students who are living alone in a dorm room or with roommates. Participants must use alarm clocks and have experience using mobile apps as we target those with high phone usage. Ideally, participants are tired in the mornings, feel rushed, and want to decrease their phone use in bed, filtering out those who naturally wake up and don’t use their phone in bed in the morning. In our questionnaire, we asked people how often they snooze, how long their screen time is, and whether they want to reduce phone usage.

Participants were expected to log their diaries every morning as they go about their routine. They wrote down their start and end times for a certain morning activity in chronological order. Below is a sample from one of our study participants.

We asked them to jot down any uses of technology and describe what triggered activities to gain insight into why, for example, they use phones in bed right after waking up. We also wanted to capture activities they do out of bed to see if time laying in bed affects the rest of their routine. They were also asked to quantify their current feeling by rating levels of stimulation, satisfaction, and connectedness, demonstrating how much value they get from technology use at different times of the morning. For more information, read here.

To synthesize our baseline findings, we created some visual diagrams. From the feedback loop, we see that people wake up feeling tired, which leads them to use their phone in bed to check notifications, triggering other scrolling, which in turn leads to feeling rushed for the rest of the routine. We see how morning phone usage is important (for getting caught up with notifications) yet deters users from getting out of bed promptly. From the connection circle, we found the time it takes to get out of bed ties closely with how/when they are using their phones.

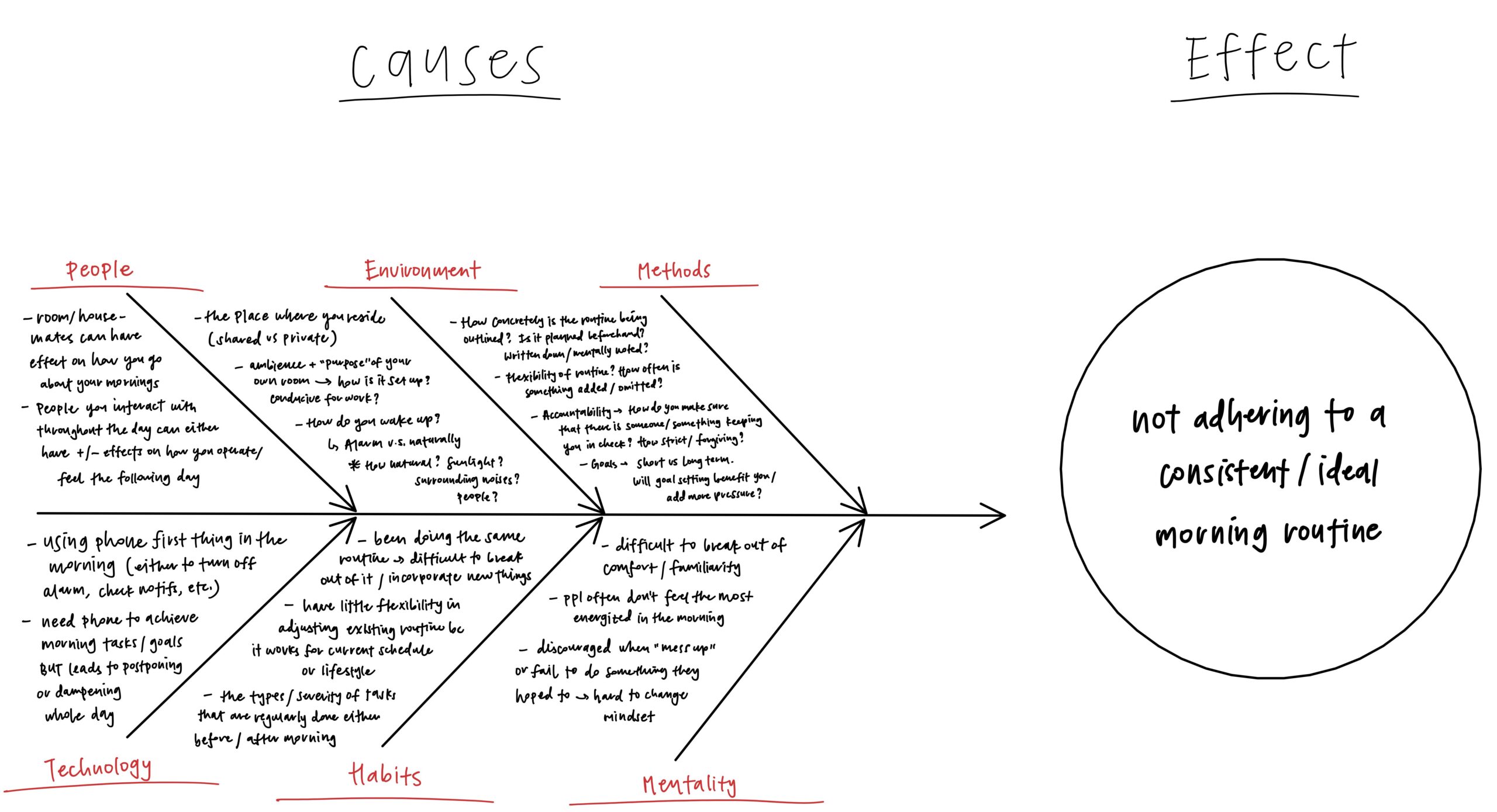

This fishbone diagram depicts varying types of reasons attributing to the lack of adherence to an ideal morning routine. It may be interesting to explore how we can leverage technology to reduce the magnitude of other behavioral causes.

Based on these learnings, we will consider how to reduce unintentional phone usage, increase intentional engagement with phones, and how to stimulate users (making them feel more awake) through other means. For more information, see blog.

Comparative Research & Analysis

After understanding the competitors, we noted three main avenues for reducing morning phone usage:

- Replace phone alarm with alternate clocks (e.g. smart watch alarm, Clocky, the Hatch lamp)

- Habit trackers and behavior change apps (e.g. Headspace, Routinery)

- Tools for tech reduction (e.g. Offtime, Channel, analog clocks)

We evaluated these along two dimensions:

- How painful/unpleasant is the intervention?

- How disruptive it is to your daily routine (+ how difficult it would be to adopt this change)?

We decided to target the Pleasant & Minimal Change quadrant as it most readily lends itself to successful interventions.

Literature Review

To ground our intervention, we also looked at academic literature regarding behavior change. Full write-up here. We had three takeaways:

- Research on behavior changes typically involves populations diagnosed with serious illnesses that necessitates behavior change. We are cautious to fully rely on such research as our users don’t have similar existential motivating drives.

- Timely feedback is important for nudging behavior. Feedback should come soon after the “wrong” behavior and be momentarily relevant for implementation.

- Smartphones are deeply engaging and well-designed for holding our attention, as diverting attention from phones a little bit can have a huge impact on users’ well-being.

Personas & Journey Maps

We created these personas because we noticed many of our participants having trouble with getting up because they were tired. We also noticed that participants felt tension between different priorities, which was a bit different from tiredness and instead connected to how they wanted to spend/prioritize their time in bed and on their phones.

These two personas are key subgroups of our target audience because they both struggle with getting up in the morning and phone use, but for slightly different reasons. Sleepy Sam feels tired in the morning, which leads to more phone use with both notifications and scrolling to try to wake up, but this leads to feeling more rushed later. Conflicted Cameron does not necessarily feel as tired, but feels torn by different tensions around staying in bed and using their phone. They currently struggle with staying in bed on their phone for too long, which leads to being rushed and mentally feeling overwhelmed by all the conflicts they face.

Sleepy Sam’s journey map shows us that the most stimulated time of their morning is actually looking at messages and scrolling. However, it is also the most stressful because Sam is aware of the amount of time they are wasting by scrolling, but thinks that screen time is necessary to feel awake. That dopamine rush can both hurt and benefit the user. In our solution, we will think up ways to make screen time more effective in a shorter period of time.

Conflicted Cameron’s journey map shows that there are multiple tensions between wanting to get up and wanting to stay in bed, as well as wanting to use their phone while wanting to stay focused and away from their phone. These tensions rise primarily when they are laying in bed, the point at which there is most opportunity to intervene.

While both Sleepy Sam and Conflicted Cameron lay in bed for quite some time on their phones struggling to get up, they use their phones in different ways. Sleepy Sam starts with notifications and gets pulled into apps that involve scrolling, which considerably increases the time they spend on their phone and thus staying in bed. Conflicted Cameron does not fall into the habit of scrolling, but rather uses their phone to stay connected with other people, which increases the time they spend in bed if they become sidetracked with some conversations.

Intervention & Product Ideation

Our competitive research led us to two design principles when brainstorming interventions:

- Avoid unpleasant approaches to behavior change

- Aim for a low-disruption intervention that is easy to implement

Next, we noticed in our baseline study that some of our participants benefited from social pressure when going through their morning routines. Hence, we added a third design principle:

- Make interventions social

This led us to consider a few highly social interventions to encourage this habit change, found in our previous blog post with detailed pros and cons. Having these three design principles made it easy to decide on a final intervention; we were able to rate each idea along each principle and select the idea with the highest score.

celebrity morning routine

group chat learnings

group chat and leaderboard

Intervention Study

For our intervention study, we decided to focus on getting users out of bed as soon as possible. For five days, we had our participants send a screenshot of their alarms in the evening and text us a photo once they got up and out of bed. We would calculate the difference between their alarm and the time the photo was sent. To learn more about the study, please refer to our 5A blog post.

We recruited 5 young adults from the ages of 18 to 30 who have trouble getting up in the morning, with a combination of participants from our baseline study and new people. The study leverages the tools of pre-commitment and social competition.

The five day study ran as follows: every evening, our participants sent us a text with the time they want to wake up in the morning and a screenshot of said alarm. The following morning, they sent us a photo once they got out of bed. The photo can depict any part of their morning routine – a selfie, their morning coffee, etc. They are encouraged to get as creative as they want, and the only rule is that they must get out of bed for the photo. Additionally, we asked participants to fill out a routine tracker to capture their morning routine.

We noted when the photo was sent and calculated the time between their alarm and wake up. In the afternoon, we tallied all of the time periods and sent out a scoreboard to all participants in the study, anonymously showing people’s standings.

Key Insights from our intervention:

- Screen time is stimulating and helps people wake up, but excessive use of technology leads to stress. Users reported feeling stimulated by screen time in the morning, as it helped them wake up and feel alert. However, they also reported feeling sucked into technology, which resulted in wasted time and ultimately led to feelings of stress and anxiety.

- Alarms come in two flavors: “Wake Up” and “Get Up.” Stress happens when you confuse the two. We noticed that some of our users set multiple alarms. When the first went off, this signaled the transition from deep sleep into awakeness. When the second alarm went off, this signaled that it was time to get out of bed. There is a difference between simply waking up and being ready to start the day. We also notice that people purposely set the 2nd alarm to ring at the very last minute so that the conscious sense of running out of time motivates them to get out of bed.

- Competition may have been ineffective due to lack of (perceived) similarity. We were surprised that sharing the wake up time scoreboard did not motivate much movement day to day. Our participants stayed in the same relative positions, though some participants spent less time in bed compared to baseline. We wonder if establishing social connection and a sense of similarity would increase the amount of healthy competition amongst users.

Storyboard & Stories

Pressured Pete wakes up sleepy and hits snooze frequently. While he checks notifications every morning on his phone, he can quickly get out of bed if there are external pressures. Our product will add a social aspect to jumpstart getting up, allowing the rest of the day to go great.

Conflicted Cameron is caught between goals: wellbeing versus productivity (staying in bed) and connection versus focus (using phone). Their morning feels rushed, with a bigger risk of feeling all negative impacts of the tensions. The product we create will help Cameron find balance and feel ready to start the day.

Current direction we are moving in

Moving forward, we have a selection of changes that we can make to our intervention based on each of our insights. These include:

- Highlight the cyclical nature of morning phone usage so that users feel informed and empowered when picking up their devices in the early hours.

- Double down on the “two alarm” framework, perhaps by explicitly asking users to set two alarms – one for wake up and one for get up.

- Establish connection and community amongst our users so that they feel more invested in the (healthy) competition of the intervention.