Baseline Study

Overview

When discussing which habits we wanted to explore, our group quickly gravitated toward personal finance and mindful consumption. After reviewing research on the psychological and emotional triggers behind impulse spending, we decided to focus on helping users build conscious spending habits. By encouraging more intentional purchasing decisions, we aim to empower users to align their spending with their values, reduce financial stress, and develop a healthier relationship with money.

Methodology

For our baseline study, we recruited 10 participants. Our target group was college students or recent graduates who want to control unconscious spending habits. To screen participants, in addition to checking if they wanted to decrease their spending, we also checked if they were able to do a four-day diary study and checked how long and which apps they used on their phone for shopping. Moreover, we checked if they had an existing budget already. We sent out a Google Form and selected 8 out of 26 participants for the diary study.

Participant Recruitment

Around 90% of the original participants were the ages of 18-23. Roughly 90% spent an hour or less on shopping online a week, with the most popular being Amazon at 92% use rate. 68% of participants don’t have a budget, and only 1 participant stuck to their budget 100% of the time. Participants were split into two groups of 40% across “I’m happy with my budget” and “I’d like to decrease it slightly,” with the remaining 20% wanting to decrease it significantly.

Key Research Questions

With this study, we hope to answer the following: what kept people from staying within budget, if they had one. In what situations did people find themselves spending outside of their original intention? What apps did people most frequent, and how did this affect their spending habits?

Raw Data -> Grounded Theory

After completing our baseline study, we synthesized our data into affinity and frequency maps. From our mappings, we developed the following 6 theories:

Grounded Theory 1: Small purchases create a psychological blind spot in spending awareness

People mentally discount purchases below a certain price threshold

- Riley Feng demonstrates this by not questioning $7 coffee purchases, only later realizing “I should like think more about like my like eight seven dollar purchases because they all add up”

- Angela Mao explicitly acknowledges this behavior, stating she “let[s] myself get away a lot of like small purchases over time”

- This psychological blind spot exists even when the cumulative impact of these purchases is significant

Value perception overrides actual need in small purchase decisions

- Emily Deng’s behavior of buying medium sizes at Coupa despite not finishing them shows how the perception of “just a few more cents” influences decision-making

- Students often choose larger sizes or more expensive versions of items despite not needing them as the immediate value proposition overshadows long-term financial impact

Grounded Theory 2: Social Spending Creates a Distinct Category with Different Decision Rules

People justify higher spending in social contexts

- Riley Feng’s choice of more expensive restaurants (Sweet Maple) is rationalized by friends’ enjoyment

- Jenna Kim explicitly categorizes social activities as “bigger purchases” worth making

- Social spending is viewed as an investment in relationships rather than pure consumption

Gift-giving operates under different financial rules than personal spending

- Chelsea Cho’s $50 juice purchase as a gift shows how normal spending limits are suspended for gifts

- Riley Feng’s $80 sweatshirt purchase for her sister while abstaining from personal clothing purchases demonstrates different standards for gift spending

- Justin explicitly states he “won’t shy away” in spending on gifts as it is a way to show that he values the recipient

- Gift purchases are evaluated based on relationship value rather than monetary value

Grounded Theory 3: Students Experience a Complex Relationship with Food Spending Despite Meal Plans

Convenience trumps financial rationality in food decisions

- Angela Mao rationalizes solo food purchases through circumstances like odd hours

- Sara’s farmer’s market purchases show how immediate access and novelty drive food spending

- The presence of a meal plan doesn’t prevent additional food spending

Food purchases generate unique guilt patterns

- Emily Deng’s self-imposed “punishment” of “really boring black coffee” after nail spending shows complex emotional relationships with spending

- Sara’s upset about unnecessary bread purchase reveals heightened awareness of food spending waste

- Students express specific remorse about food purchases that duplicate meal plan coverage

Grounded Theory 4: Large Purchases Follow Distinct Psychological Patterns

Significant purchases involve more deliberate decision-making processes

- Jenna Kim’s multiple-week consideration period for large purchases

- Riley Feng’s weeks-long deliberation on expensive clothing

- Evelyn’s month-long checking of flights for a trip with a friend.

- Planning creates a sense of control and satisfaction with larger purchases

High-value purchases are often rationalized through long-term benefit perception

- Riley Feng’s classification of Pilates as “the best thing that I spend my money on” despite being “unsustainably expensive”

- Vanessa’s acceptance of high hair care costs due to confidence benefits

- Justin’s plan to spend more on a speaker since it is a “high utility item”

- Large purchases are evaluated through a different framework that emphasizes long-term value

Grounded Theory 5: Financial Tracking Behaviors Show Systematic Avoidance Patterns

Multiple payment methods obscure total spending awareness

- Riley Feng’s practice of splitting purchases between credit and debit cards to avoid confronting total spending

- Evelyn’s conception of beginning a new month as a “clean slate” discourages any reflection on spending habits

- The absence of systematic tracking leads to spending surprise when logging is implemented. Payment method diversification serves as a psychological buffer against spending awareness

Return policies create a false sense of spending security

- Vanna’s extensive Amazon returns demonstrate how easy returns reduce purchase hesitation

- Justin’s refusal to shop online for clothing at brands without easy return processes reveals a conception of the return process as an inherent trial period

- Return possibilities are used to justify initial purchases and the ability to return items creates a temporary ownership mindset that facilitates spending

Grounded Theory 6: Online and Offline Spending Follow Distinct Behavioral Triggers and Awareness Patterns

Online and offline spending have different trigger mechanisms

- Physical proximity drives offline purchase

- Sara and Riley’s farmer’s market spending

- Online spending is primarily triggered by digital stimuli like sales emails and idle browsing.

- Riley and Chelsea’s reception of sales emails drove them to buy baked goods and clothes

- Offline spending tends to be more spontaneous and environment-dependent

- Evelyn’s purchase of chips for a quick snack at the office occurring on sight

- Online purchases are either highly intentional or result from boredom-induced browsing

- Riley and Jenna only browse online when extremely bored in class

Online spending creates a different level of purchase awareness

- Digital record-keeping makes online spending feel more “real” to students

- The act of logging purchases created heightened awareness of overall spending patterns for all of those who did the diary study

- Riley and Jenna found it easy to remember all of their recent online purchases

- The digital trail of online purchases provides better visibility into cumulative spending

- No one was surprised by their shopping history on Amazon or general web browser shopping history

- Online shopping is often reserved for necessities and repeat purchases, suggesting a more deliberate approach

Questions for Further Research

- What determines the psychological threshold for “small” purchases that escape scrutiny?

- How do social relationships influence spending beyond immediate social situations?

- What impact does the ability to split payments across multiple methods have on spending control?

- How do digital payment methods and online shopping platforms influence spending awareness?

- What role does the immediacy of physical shopping play in purchase decisions versus the delayed gratification of online shopping?

- How do different shopping environments (digital vs. physical) affect impulse purchasing behavior?

System Models

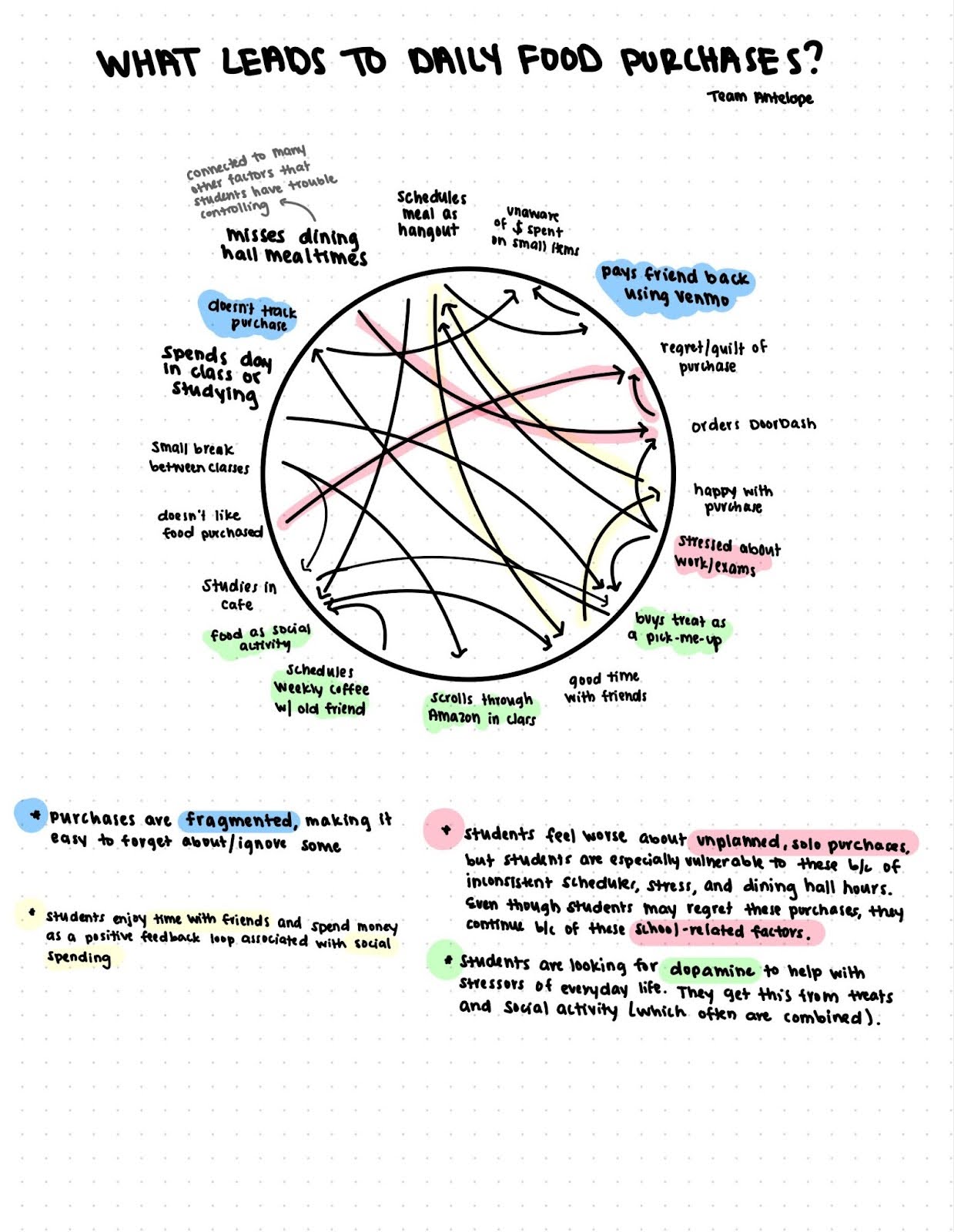

From our baseline study and raw data, we noticed that a possible area for intervention is with daily food purchases. Participants tended to feel the most guilt and regret surrounding food purchases that they deemed as unnecessary, yet conversely felt most satisfied with purchases that were a part of a social activity, like going out to eat at a restaurant with friends. So, food is particularly on students’ minds and contributes to their monthly spending in a meaningful way.

The connection circle below explores more of the daily thoughts and actions that lead to food purchases, and why some are viewed positively while others are viewed with guilt.

From this circle, we see a feedback loop with social spending: students schedule meals as hangouts, have a good time, feel good about the purchase, then subsequently continue to plan these outings. But, factors such as the dining hall hours and school-related stress contribute to impulse food purchases (like ordering DoorDash at night). Even though a student may regret these purchases, the outside factors continue to influence them to buy more food, continuing the cycle even if the student feels regretful after each instance.

This second model is a bit more general and focuses on why students are spending more than they anticipate each month, a very common theme among our interviews. This model highlights that social spending is viewed fundamentally differently than other types of spending. Students are more willing to spend money on or with others. Like the connection model, this model also highlights how unique aspects of life for university students encourages spending. Finally, it demonstrates that although food was a common expense and theme for our baseline study, other purchases still contribute greatly, such as larger purchases or recurring ones (gym memberships, hair appointments, etc). But, since more planning goes into these purchases and since some are viewed as fundamental to their health, students are more easily able to justify them.

Insights from these models give a few interesting opportunities for intervention:

- Find ways to suggest social activities that don’t center around pricey food, allowing students to still benefit from social interactions while also saving. But, if students feel justified in their social spending at restaurants, will they be motivated to do this?

- Bridge the gap between planning and action when it comes to smaller purchases so students feel just as empowered with small purchases as they already do with their larger ones. Apply micro-planning strategies to daily expenses, helping students manage smaller purchases.

- Instead of focusing on cutting spending, we can try to highlight spending reallocation, showing students how small daily savings can fund larger experiences they care about, like travel or concerts. This approach aligns with how students already plan larger purchases and may make budgeting feel more rewarding.

Secondary Research

College students often accumulate credit card debt due to easy access to credit, lack of financial education, and the normalization of debt (Leclarc, 2012). Factors like gender, academic performance, family income, and financial aid influence debt likelihood, highlighting the need for targeted financial interventions. With 84% of college students owning credit cards (averaging 4.6 per student), promoting financial literacy and budgeting skills is essential. Psychological factors such as normative influence, perceived barriers, and perceived control also shape budgeting success (Kidwell, 2003). Research suggests that interventions boosting confidence in financial management and emphasizing emotional benefits can encourage better spending habits.

E-commerce and social media fuel impulse spending through reduced perceived risks, social influence, and seamless purchasing experiences, yet many impulse buyers seek tools that encourage deliberation, spending limits, and cost awareness (Moser, 2019). Offline shopping relies more on sensory experiences and in-store promotions, whereas online platforms amplify impulsive buying through targeted ads and convenience (Aragoncillo, 2018). Implementing friction-based interventions—such as delaying purchases or making costs more salient—can help curb impulsivity. These findings suggest that tackling impulse spending, especially among college students, requires a combination of financial education, psychological motivation, and digital friction strategies to foster long-term financial discipline.

For our comparative research, we wanted to examine what home solutions there were. We also wanted to see if people were willing to pay for solutions, and what form these solutions took (i.e. browser extension, apps, etc.). Moreover, we wanted to examine if these solutions took place retroactively, as in after our audience purchased an item, or immediately during a purchase. We also wanted to see if the tool required manual input or helped our user more automatically.

One of the home solutions was using a budget sheet on Excel or Google Sheets. We saw one of our participants use this extensively, but often overshot their intended budget still. Budgeting spreadsheets are a free and highly customizable way to track spending, helping to curb impulse purchases. While they offer flexibility and can be enhanced with extensions for deeper insights, they require significant manual effort and don’t actively intervene in spending decisions, thus creating friction in their use rather than the spending habit. Their key value lies in accessibility and personalization.

Chase Mobile shares similarities with budgeting spreadsheets in that both allow users to track their spending and manage their finances. Like spreadsheets, Chase provides an overview of financial activity, helping users monitor expenses and make informed budgeting decisions. However, Chase Mobile reduces the manual effort required by automatically categorizing transactions, estimating monthly income, and tracking bills, whereas budgeting spreadsheets require users to input and organize their data manually. Additionally, Chase integrates budgeting with banking, providing real-time spending insights and a seamless, all-in-one financial management solution that requires minimal upkeep—features that traditional spreadsheets lack.

Spend Wise helps prevent impulse spending by leveraging evidence-backed interventions that promote self-control in online purchases. Research on impulse buying interventions, such as Reflection, Distraction, Desire Reduction, and Salient Cost (Han, 2021), has shown that prompting users to pause and reconsider their purchases effectively reduces impulsive buying urges. Spend Wise integrates these strategies by allowing users to save items to a wishlist, introducing a delay before purchase, and guiding them through mindful evaluation questions. Additionally, the app aligns with nudge-based interventions (Mandolfo, 2022) by increasing interactional friction (requiring users to take extra steps before buying), providing timely feedback on spending habits, and engaging distraction by shifting attention away from immediate purchases. By incorporating these proven methods, Spend Wise helps users build long-term habits to resist unnecessary spending.

Similarly, Orca targets impulsive spenders by reframing spending habits—encouraging users to transfer money into savings instead of making a purchase. It also offers goal-oriented nudges, analyzing past spending behavior to suggest when and where users can save. While Spend Wise focuses on mindful decision-making and delayed gratification, Orca emphasizes habit formation and redirection of spending urges. Both apps fulfill a need for lasting behavior change, helping users develop financial awareness and resist unnecessary spending.

Apps like Chase, Orca, and Speedwell effectively assist users in tracking their spending, but they lack a gamification element, which could enhance user engagement and long-term behavior change. Studies show that gamified distraction strategies are more effective than substitution strategies in reversing impulse e-buying behavior (Tobon, 2024). Gamification, such as offering rewards or challenges for saving money or avoiding impulse purchases, could make the process more interactive and motivating. Incorporating game-like elements, such as leveling up or earning badges, could make the experience feel less transactional and more rewarding, encouraging users to stick with their financial goals.

Moreover, a social component could be highly beneficial, as seen with communities like r/shoppingaddiction, where individuals share experiences and offer support. Integrating social features into these apps—such as group challenges, progress sharing, or accountability partners—could provide additional motivation and a sense of camaraderie. Therefore, adding gamified distractions, rewards, and social support into the user experience could foster healthier financial habits, much like how communities provide emotional and practical strategies for managing shopping addiction.

Proto-Personas

As visualized by our system models, most of our participant’s spending habits revolved around food a social activities. Broadly we can divide our audience into two proto-personas that collectively combine to cover their behaviors.

| Drawing | Name | Social Simon |

|

Activated Role | Friend |

| Goal + Motivation |

|

|

| Conflict |

|

|

| Attempts to Solve |

|

|

| Setting/ Environment |

|

|

| Tools + Skills |

|

|

| Habits |

|

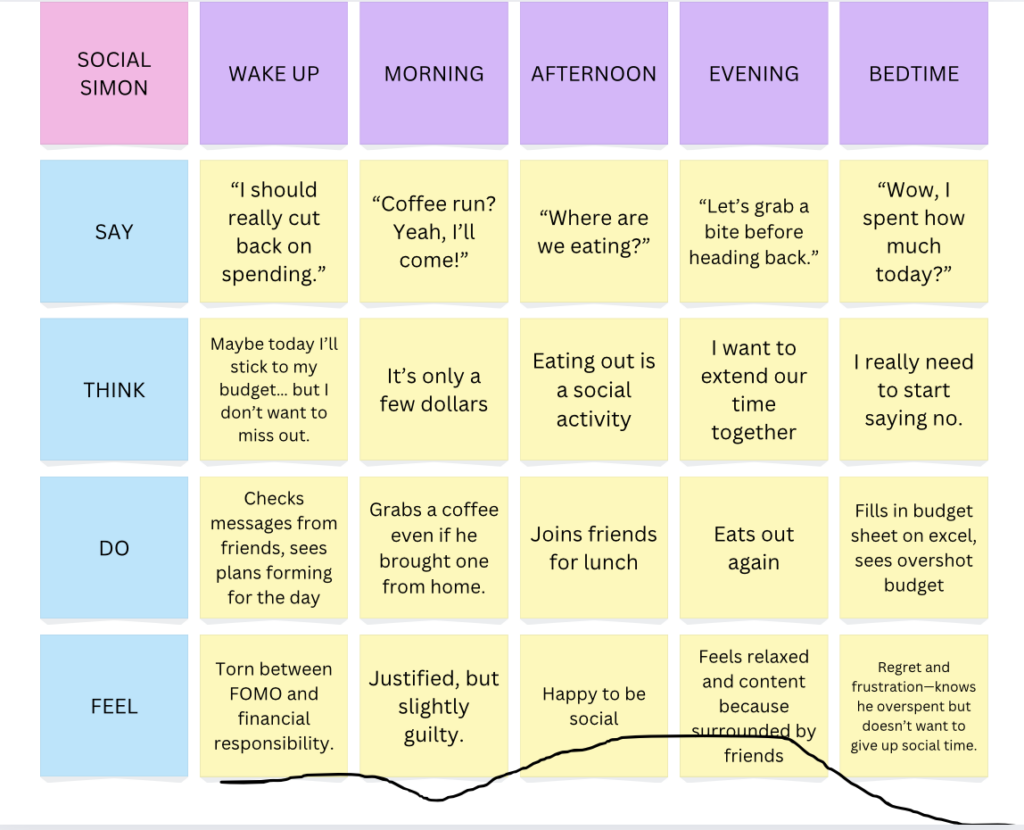

Our first persona is Social Simon, highly social spender who prioritizes shared experiences over financial restraint. He thrives on social interactions and sees outings as opportunities to strengthen friendships, often opting to join group activities even if they involve unplanned expenses. His spending habits revolve around food—eating out for lunch and picking up dinner with friends on the way back home.

While he tracks his expenses using budget sheets, he finds it difficult to say no without feeling like he’s missing out. Moreover, when spending with friends, he rarely tracks Venmo or Zelle. The enjoyment of time spent with friends outweighs the concern for money in the moment, but by bedtime, reality sets in as he logs his expenses and realizes how much he has spent. Despite the occasional regret, he struggles to break the cycle, as socializing remains a core part of his identity and happiness. He’s unsure of how to proceed because he doesn’t want to cut down his social time, but finds himself overshooting his budget often.

An overview of Simon’s day reveals pain points before and after each social event which stem from a fear of missing out and awareness of his spending, respectively. The strong mental connection between socializing and spending money makes it very difficult for Simon to see how he would be able to reduce his spending without reducing his socialization. However, we can notice that his mood is heightened simply in the presence of others. Thus, he should be able to achieve the same affect without placing a burden on his finances. The most ideal time to be able to reach Simon would be near the beginning of his day when friends begin to make plans and he considers his budget for the day.

| Drawing | Name | Seeking Sara |

|

Activated Role | Sweet Treat Seeker |

| Goal + Motivation |

|

|

| Conflict |

|

|

| Attempts to Solve |

|

|

| Setting/ Environment |

|

|

| Tools + Skills |

|

|

| Habits |

|

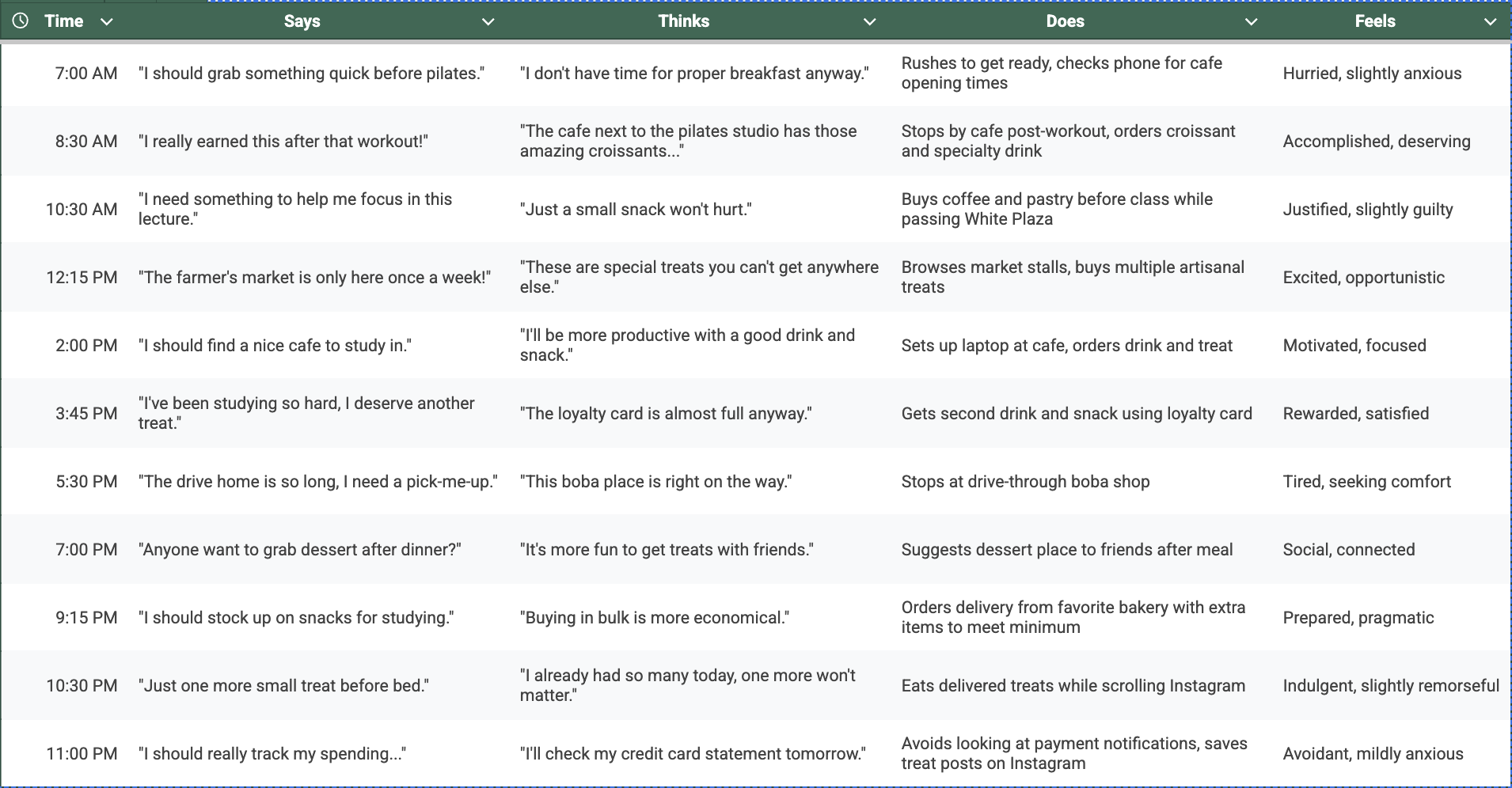

Our second persona is Seeking Sara, a young, active individual who struggles with impulsive spending on sweet treats and snacks.

Living in a vibrant area with easy access to bakeries, cafes, and food markets, Sara frequently encounters opportunities to purchase treats throughout their daily routine. Whether it’s grabbing a pastry after morning pilates, stopping by the farmers market between classes, or joining friends for post-dinner dessert, Sara’s environment is filled with temptations that align with their love of sweets.

What sets Sara apart from a typical social spender is their tendency to purchase treats even when alone. The motivation isn’t primarily social – it’s driven by a genuine love of sweets, a desire for novelty (like limited edition items), and using treats as self-rewards for accomplishments. This pattern is particularly pronounced because Sara doesn’t mentally register purchases under $10, making it easier to justify these small indulgences without feeling their financial impact in the moment.

Despite having access to tools that could help monitor spending (like digital credit card statements), Sara actively avoids reviewing their financial records. They’ve seamlessly integrated modern payment methods like Apple Pay into their routine, further reducing the friction of making purchases. While RF has friends who could potentially help curb this behavior, they haven’t made any concrete attempts to address their spending habits.

Sara’s daily patterns create multiple vulnerability points for unplanned purchases. Their busy schedule often leads to skipped meals, creating situations where hunger combines with convenience and desire for treats. The prevalence of food-centered social activities in their life adds another layer of spending opportunities, as Sara finds it difficult to decline when friends suggest getting dessert or boba after meals.

This spending pattern is sustained by Sara’s habit of checking promotional emails from bakeries and regular visits to local food markets, keeping them well-informed about available treats while potentially triggering more purchases. The combination of their genuine enjoyment of sweets, environmental access, and lack of small-purchase awareness creates a cycle that remains unaddressed due to their avoidance of financial self-reflection.