Part 1: Synthesis

From our Baseline Study to our Grounded Theory

For our project, we chose to delve deeper into understanding the focus patterns of high school students, recognizing the pivotal role that maintaining concentration plays in their academic achievements and overall mental health. Our baseline study employed a comprehensive approach, collecting a combination of quantitative and qualitative data from a broad demographic of high school students around the world, through daily surveys as well as a pre- and a post- study interview. This data collection aimed to shed light on the specific difficulties students encounter in achieving and sustaining focus during study sessions, the strategies they adopt to manage distractions, and how external factors such as deadlines and technology usage influence their ability to concentrate.

A particularly striking insight was the widespread issue of the “activation threshold” for starting tasks. Many students reported a tendency to delay beginning their work, engaging in unrelated activities to avoid facing their assignments. This procrastination isn’t merely a matter of time management; it reflects a deeper psychological barrier that students encounter when approaching tasks perceived as challenging or time-consuming. Such behaviors underscore the need for strategies that lower this threshold, making it psychologically easier for students to initiate a work session. The interviews also revealed that once students overcome the initial barrier and begin their work, many find it significantly easier to maintain focus and complete their tasks. Stefanie’s experience, where starting work for even a short period led to prolonged periods of productivity, highlights the importance of developing strategies that encourage students to take the first step.

Another interesting trend was the role of external pressures in shaping study behaviors. While conventional wisdom often views pressure and stress as detrimental to academic performance, our participants’ feedback, particularly from Juan and Mira, painted a more nuanced picture. The right amount of pressure, such as impending deadlines or the prospect of collaborative study sessions, was often cited as a catalyst for focus and productivity. This revelation points to the potential benefits of structured, supportive pressure in educational settings, challenging us to rethink how we can harness these dynamics to enhance student focus without leading to burnout.

The impact of technology on focus was another critical area of insight, underscored by the unavoidable nature of digital devices in the completion of schoolwork. While these tools are integral to modern education, facilitating access to information and enabling innovative learning methods, they also represent a significant source of distraction. The experiences shared by our participants, including Noa’s struggle with smartphone distractions and Juan’s preference for printed materials over digital ones, illuminate the complex relationship between technology and focus. These insights lead us to consider how educational tools and practices can be designed to minimize distractions while still leveraging the benefits of digital resources.

System Models

The mapping process from the raw data was the same for both models. We went through all the data (pre-study interview, data collected in-study, post-study interview), for each participant, and summarized findings on post-it notes. After some distilling, the above overview resulted. The system models are both built on the insights from this step, and look as follows:

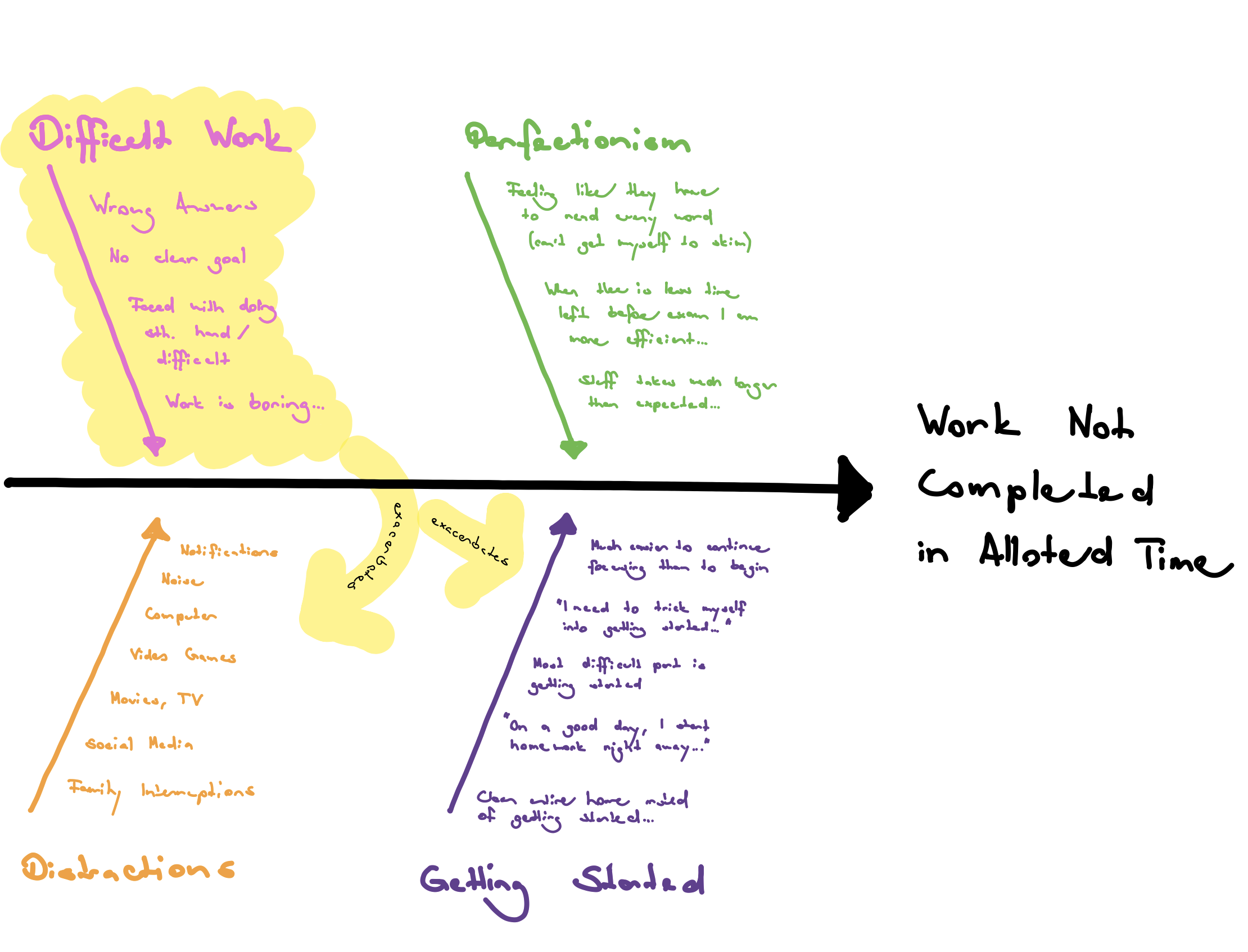

Model #1: Fishbone Diagram

Insight derived: There are multi-faceted reasons for people not completing their work, or not completing their work in time. It is not just about focus: people not finishing in time can be a result of perfectionism (upper right corner), or not getting started. The most interesting insight for us has been that focus is not something that is innate, with some people having better strategies to manage it, but that it is highly context dependent: we noticed that the perceived difficulty of work significantly impacts symptoms of what we commonly believe to be a lack of focus: if a task is hard, the Instagram is all the more alluring, and we distract ourselves more easily… with hard tasks, it’s not that we get distracted, we want to distract ourselves. And the same goes for getting started – it’s much harder if we’re frustrated by a seemingly difficult task – whether it is overwhelming due to its sheer size or because it’s out of our wheelhouse.

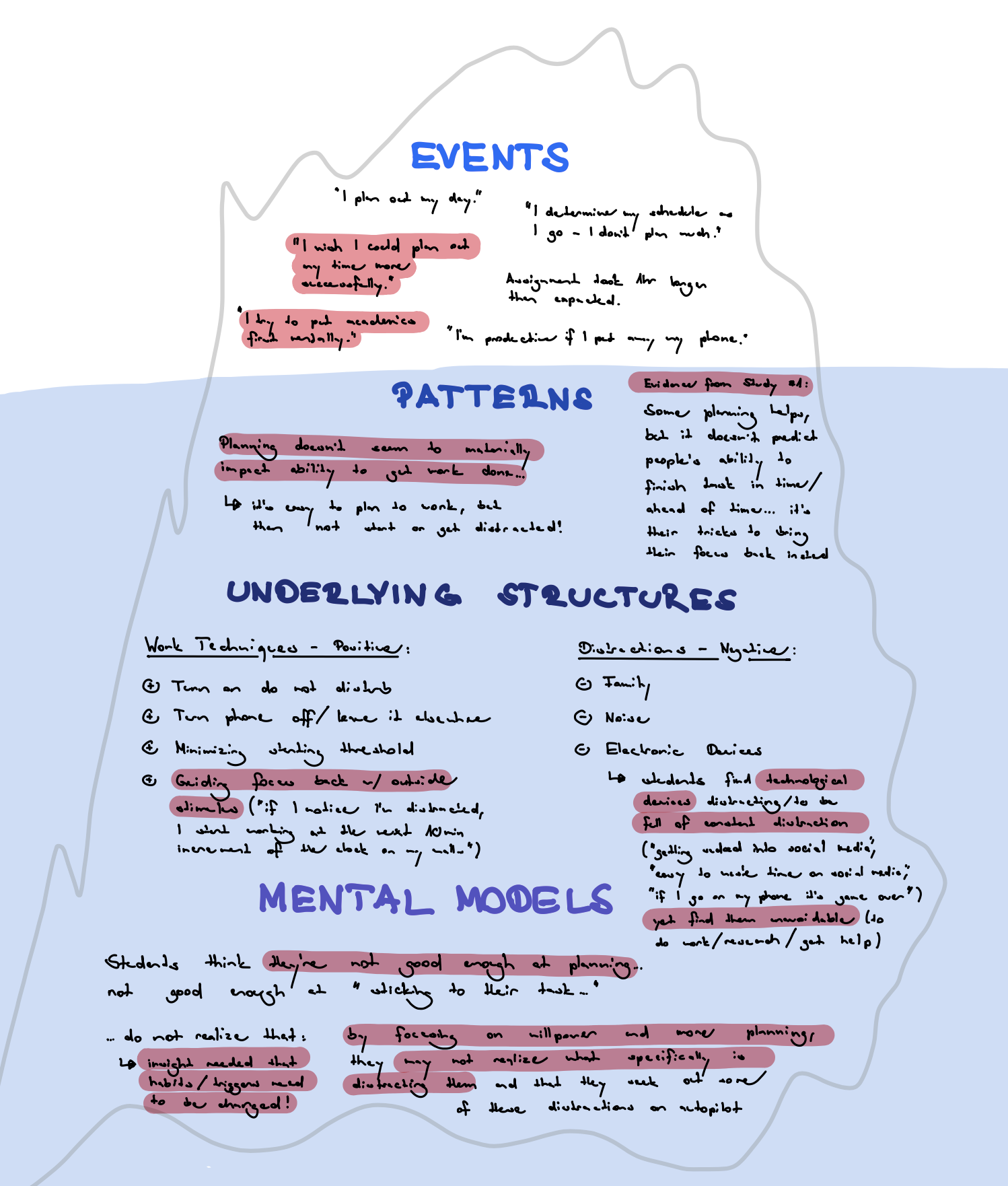

Model #2: Iceberg Model

Insights derived: From the Iceberg Model, we learned that many high school students wish to plan their days and their work better. While some planning is helpful, it doesn’t predict people’s ability to actually stick to their plans. Rather, habits such as guiding your focus back once you got distracted, and noticing you are distracted in the first place seem to help the most. Other habits such as turning laptops on do not disturb, or leaving the phone in a different room can help, too, but the challenge there is that people need their devices to do work and need to open their messages to interact with peers and teachers. As such, the key insight was the following: while students find their devices distracting, they also rely on them and can’t easily shut out all the distractions. Instead, they need to learn what exactly makes their mind wander, and identify patterns on when they get distracted and what distracts them to effectively improve their focus – but many are unaware of how often they are focused or simply think they need to stick to their plans better.

Secondary Research

Following our grounded theory and development of system models, our team looked into secondary research to gain greater perspective on the subject of inability to focus in high school students. We researched several academic articles and journals related to our topic, which unveiled insights relevant to our study and target audience. We also completed comparative research of products, applications, and services in the same space as our research.

Literature Review

To gain a greater understanding of our topic, our team analyzed ten academic articles of relevance. We made a particular effort—as with our baseline study participants—to identify research articles hailing from several different countries. The articles we explored came from the United States, the United Kingdom, Turkey, Spain, and Finland. Some were studies of what causes inability to focus in high school students; others were specific interventions with the goal of improving focus in participants. Several common themes emerged across the literature: (1) high schoolers’ ability to focus is correlated with their reading habits and physical activity habits (2) high schoolers focus better when work is engaging and appropriately challenging (3) both teaching methods and teachers play a role in high schoolers’ focus during school, and (4) smartphones, even when turned off, have a significant negative impact on focus

The first insight—that high schoolers’ ability to focus is correlated with their reading and physical activity habits—was highlighted by three articles we read. Evidence suggests that regular physical activity can help adolescents sustain their attention longer. Similarly, engaging in reading is positively linked to better focus. Unfortunately, high schoolers read far less than they used to due to the increased presence of smartphones. While our group wasn’t particularly interested in studying reading nor exercise (as neither topic came up frequently in our baseline study), this insight sheds light on how strengthening other habits can help to strengthen focus.

The second insight we uncovered is that high schoolers focus better when work is engaging and appropriately challenging. One study comparing high schoolers in Finland and the US found that when students are aptly challenged, they experience increased confidence, success, and happiness—each of which may improve focus. Interestingly enough, engaging work is also often the trigger for hyperfocus. Hyperfocus is a difficult-to-maintain state and most common in individuals with ADHD, autism, and schizophrenia, but it is interesting because it can offer insights into focus and attention. Ultimately, understanding that fun and suitably challenging work drives focus is incredibly important as we start our project design.

The next insight is that both teaching methods and teachers play a role in high schoolers’ focus during school. One article we read emphasized that teaching methods can significantly shape students’ focus, while another challenged that notion by arguing that teachers are more important to the equation. This insight intrigued us as we later brainstormed solutions, as perhaps a useful solution would involve not just high schoolers, but their teachers, too.

The final key insight we derived from our literature review is that smartphones have an extremely negative impact on focus. While this insight alone came to us as no surprise, the three studies we read gave shocking details about this. One detail most relevant to our study is that the mere presence of smartphones—even when turned off or not in direct view—reduced attentional performance in high school students. Moreover, the presence of smartphones leads to slower working speeds. This fascinating insight led us to an important revelation about our future solution: the less our solution requires a smartphone, the better. This could mean our mobile app solution should require users to spend very little time on their phone; it could also mean that our solution shouldn’t be a mobile app at all. Our group thought back to this insight repeatedly throughout subsequent ideation processes.

Comparative Research

An important next step of our process was conducting a comparative analysis of ten competitors in the same focus space. Analyzing competitors was extremely helpful to examine strengths and weaknesses of existing focus products, to explore various UIs and their common features, and to extract insights as to how we might create something unique. While each competitor we analyzed provided unique insights, we will focus on just three of the more distinct ones: (1) One Sec, an apps which uses mindfulness to block out distractions (2) Forest, an app that encourages sustained focus periods, and (3) Focusmate, and app that leverages coworking to inspire focus.

One Sec is an iOS and Android app which combat digital distractions. It does so in a very unique way: unlike traditional distraction blockers, it prompts users to spend a mindful moment reflecting on their intention before proceeding. It effectively adds a “mindful barrier” to impulsive app usage or web browsing. One Sec is a strong app because it offers cross-platform functionality to help users manage distractions across their most used devices. It skillfully integrates the practice of mindfulness into daily technology use, supporting overall mental well-being. One Sec is also strong because it is customizable: users can tailor the app’s prompts and delays to fit their personal goals and the level of intervention they need. On the flip side, One Sec isn’t ideal for users lacking the mental willpower to block out distractions. A user like this would benefit more from a strict distraction blocker. In essence, the effectiveness of One Sec heavily relies on the user’s willingness to engage with the mindfulness prompts and respect the intentionality process. The key insight we derived from One Sec is as follows: integrating features that track and report on the frequency of interruptions and user compliance with mindfulness prompts could offer valuable insights into digital habits, further supporting users in their journey towards more intentional technology use.

The next app we will shed light on is Forest, an app meant to encourage sustained focus periods and curb phone addiction through growing a virtual tree. It’s intended for use by anyone who feels distracted by their phone, including teens. Users set the time for a focus session, plant a seed, then set aside their phone. Completing their session phone-free rewards users with a fully-grown virtual tree; if a user instead gets distracted by their phone during their session, the tree withers. Forest is a strong app because it has a calming, aesthetic UI. It is effective at motivating users to stay away from their phone using the reward and deterrent of a grown tree and a withered tree, respectively. Forest also partners with real tree-planting organizations, offering the option to plant real trees with virtual currency and thus contribute to environmental conservation efforts. The app has a few notable weaknesses, too. It indiscriminately counts phone use during work sessions as wrong, failing to distinguish between productive and non-productive phone use. Forest also doesn’t physically restrict access to other apps or websites. Therefore, the effectiveness of the app relies on the user’s personal commitment to it. Key insights we can take away from Forest come from its UI and its nod towards altruism. Forest’s calming UI is a great example of how an app’s functionality can be enhanced by its aesthetic. The app skillfully connects improving personal focus with other things the users might care about, such as altruism. These insights are worth considering when implementing our solution.

Finally, an app of interest is Focusmate, a Zoom-like software which encourages focus through virtual coworking. Users can book a session when they want to focus, get matched with a partner, and then join a video call with them. Users are encouraged to share their goals for the session with their partner, which can include any kind of focused work (homework, cooking, exercising, etc), as the emphasis is on coworking more than the task itself. In fact, Focusmate’s website says “the main thing is to set up your camera so that your partner can see you while you focus on your task(s).” Focusmate is a strong application because it is built around social, human connection. Many people—including some of our interviewees—find working around others to be encouraging. Focusmate has strong features such as chat, virtual backgrounds, and automatic calendar insights. Users can also customize their coworking sessions by choosing one of three different session lengths. With that being said, there are some downsides. For starters, Focusmate is not free after the first few sessions, which is a significant barrier to people using this application. There could also be safety or privacy concerns. A weakness more relevant to our study is that the presence of another person may be distracting for some people, rather than helpful. One key insight we gathered from Focusmate is that your environment—and specifically the people in it—play a significant role in your focus level. Focusing around close friends may be tough, but a product that encourages learning to focus around classmates, acquaintances, or even strangers might be really useful for high schoolers accustomed to being surrounded by students for half of their day.

Conducting our literature review and comparative research on ten articles and ten applications (three of which have been discussed) provided us with many great insights as we transitioned to creating proto-personas and journey maps, and later creating our intervention study.

Proto-Personas

After our baseline study and secondary research, our team reviewed our transcripts and notes to create proto-personas for 5 of our interviewees (SH, DB, SV, NB, and JB). Upon discussion, we realized that there are 2 significant, recurring reasons preventing our interviewees from getting work done. Firstly, while technological devices are crucial in completing homework, they also contain sources of distraction, such as notifications and social media (this was mentioned by DB, SV, NB, and JB). Secondly, having difficult tasks to do can incentivize procrastination, which can only be combated by the time pressure from impending deadlines (this was mentioned by DB and JB).

Thus, we decided to narrow our focus down to 2 proto-personas that best demonstrated the 2 conflicts. We chose NB for the first conflict and JB for the second conflict. We present the 2 proto-personas below.

—

Proto-persona 1

Name: NB

Role: High school student who heavily utilizes technological devices for both schoolwork and leisure.

Goal: Become a more productive student. Focus on the main tasks at hand.

Conflicts

- Lacks the discipline to study before pursuing leisure activities.

- Difficulty focusing in certain environments, such as at school and on the train.

- Technologies needed for work — such as her laptop — are also sources of distraction.

- Switching between different platforms when studying is exacerbating.

- Inability to focus on key points. For example, she would try to skim an article for its main points but ends up reading every word.

Attempts to solve

- Putting her phone away before studying.

- Tried the 25-minute work / 5-minute break tactic, but stopped using it because she would rather get things done in one go.

Setting and environment: At home

Tools and skills: She uses her phone and laptop for study purposes. For example, if she has questions about schoolwork, she might take a photo and text her friends for help. She does assignments using her laptop.

Routine:

- Wake up around 6:30 AM.

- Take the train to school (which runs from 8 AM—3 PM).

- Take the train back home.

- Do homework and pursue leisure activities (with dinner around 6 PM).

- Go to bed around 9—10 PM.

—

Proto-persona 2

Name: JB

Role: High School Student from Chile who wants to be productive and enjoys socializing with friends and doing athletic activities.

Goal: Minimize frequency and length of distractions during a work session to make the most of the time he spends studying. Perform well in school and still have time for other activities (competitive sports, social gatherings, etc.).

Conflicts:

- Laptop used both for studying and for social media, streaming platforms, and sports games.

- Frustration / difficult tasks make them want to get distracted / procrastinate.

- Difficulty to work in certain places (for example, in school, as it “feels like free time”).

- Needing the pressure and stress of an imminent deadline to start and maintain focus on a task.

- Finding other things a lot more interesting than school work (for example, what the score is on a football game is more important to them than what the answer to his math problems is).

Attempts to solve:

- Leaving his phone on their bed while they study.

- Studying with a friend to hold each other accountable.

- Printing out worksheets to avoid using a laptop to study.

Setting and environment: Different rooms at home (he likes to change study environments frequently. E.g. his room, the dining room, his sisters’ rooms, etc.).

Tools and skills: Laptop, printer, and worksheets to study. Phone to communicate with friends and with teachers (his teacher will offer to help via WhatsApp). The ability to focus in a noisy environment, and to work well under pressure.

Routine:

- Wake up at 6:30 AM.

- Drive to school at 6:50 AM.

- Arrive at school at 7:20 AM.

- Classes start at 7:45 AM and end at 3:45 PM.

- Arrives home at 4:30 PM.

- Watch TV/ eat a snack for tea time 4:30 – 6PM.

- Homework / Study 6 – 8:30 PM.

- Dinner 8:30 – 9:30 PM.

- More homework / studying or watch a show 9:30 – 11:30 PM.

- 11:00/11:30 PM Bedtime.

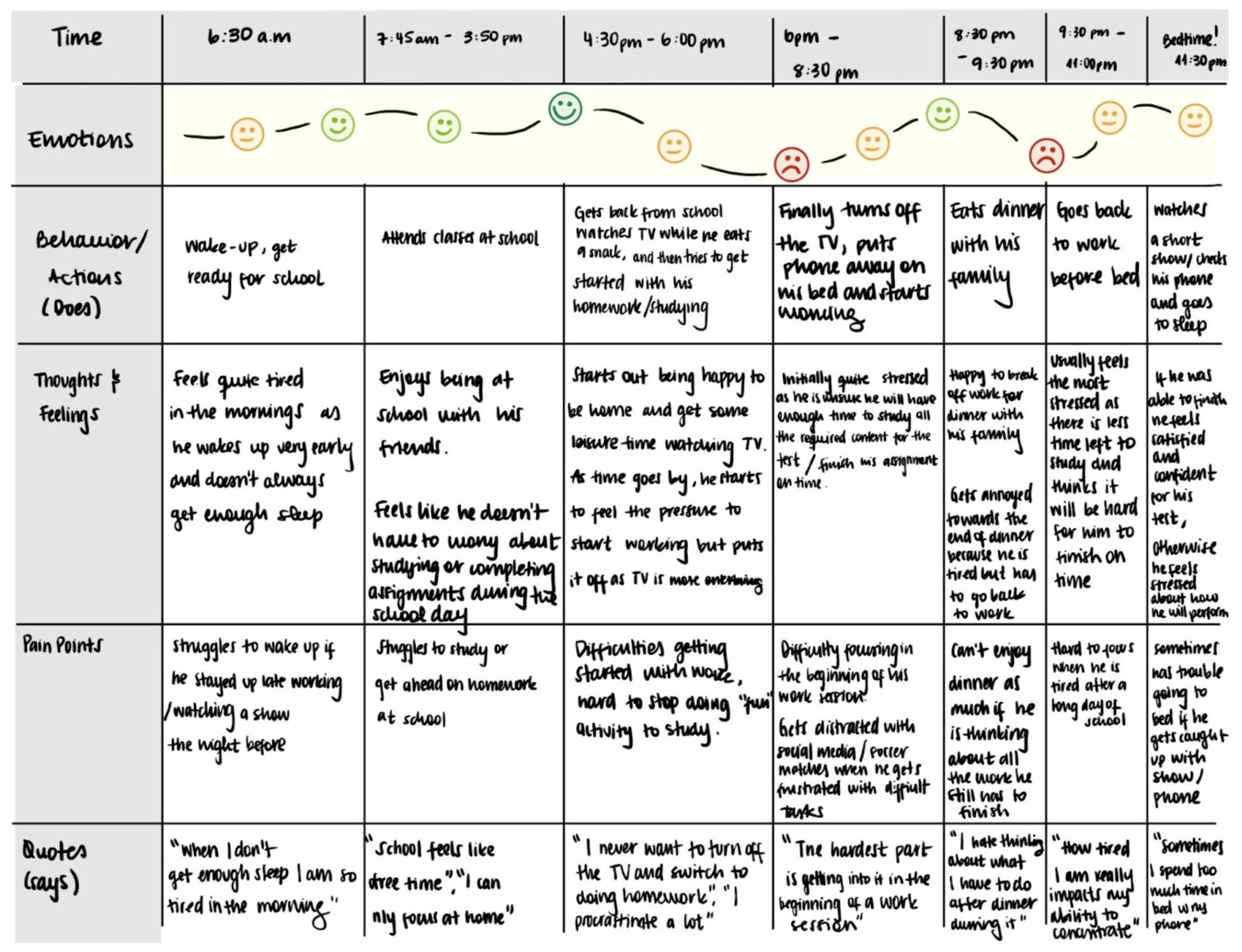

Journey Map

After crafting our proto-personas, we created journey maps to dive in further into the actions and feelings of our proto-personas. Journey maps allow us to visualize the journeys our participants take throughout a given time period.

The journey map for NB represents various activities in NB’s daily routine, including attending school and commuting home by train, starting on her homework, having dinner, studying for a test, and going to bed. At each phase, we describe NB’s emotional state; her actions, thoughts, and feelings; as well as the pain points relevant to her struggle to focus or accomplish tasks. Key pain points include constantly switching her attention and getting frustrated that schoolwork requires her to use the same technological devices which contain sources of distraction. Here is NB’s journey map:

The journey map for JB also walks through JB’s day, from his wake up at 6:30am to going to bed at 11:30pm. At each time chunk, it shows JB’s behavior, thoughts and feelings, pain points, and emotions. Additionally, this information is supported by quotes from JB’s pre- and post-study interview. A pain point that stands out is that JB finds it especially difficult to get focused at the beginning of a work session. In his interviews, he said, “I never want to turn off the TV and switch to doing homework” and “I procrastinate a lot”. JB’s interesting journey map is shown here:

Ultimately, creating journey maps was a vital point in the transition between our baseline and intervention study. The journey maps for NB and JB (and for our other participants) highlight the thoughts and pain points going through our personas’ minds. Understanding these pain points and where they fall in the timeline of one’s day shows us some of the places where we could introduce an intervention.

Part 2: Intervention Study

Our Ideation Process

Our ideation process began with individual brainstorming focused on three key insights identified from our grounded theory. Each team member dedicated five minutes to brainstorming on each insight, aiming to generate a wide range of ideas that could potentially address the specific challenges of focus, procrastination, and the unavoidable distractions from technology faced by high school students.

After the individual brainstorming sessions, all ideas were consolidated into a shared Google Doc. To further refine our ideas, each team member then highlighted their favorite ideas within the document. This step was crucial for identifying which solutions resonated most strongly with the team, based on each of our individual perspectives, before we were affected by each other’s opinions. Following this, we engaged in a group discussion to evaluate the highlighted ideas. The discussion focused on the merits of each idea, considering factors such as practicality, potential effectiveness, and the ease with which each solution could be implemented in a high school setting. We only retained ideas that were highlighted and unanimously agreed upon as good by the entire team.

Then, we repeated this entire process, but this time coming up with only dark horse ideas to test each of the key theories that we had developed through our baseline study. The final discussions led us to choose two of the ideas developed in the first round, and one of the dark horse ideas from the second round, to storyboard and present to the class. This final selection of ideas represented the solutions we collectively believed had the most significant potential to address our key insights effectively, and were most interested in receiving feedback for.

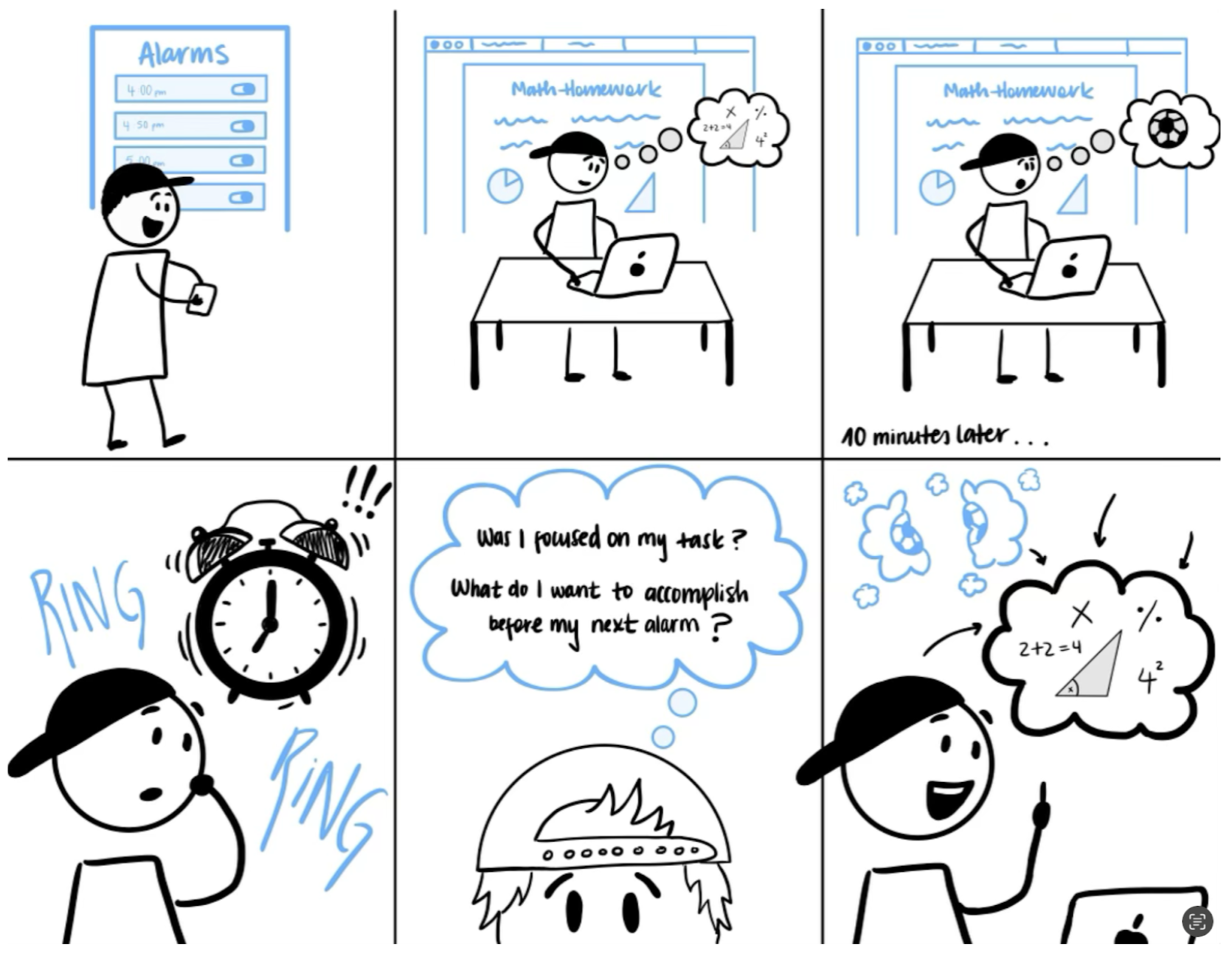

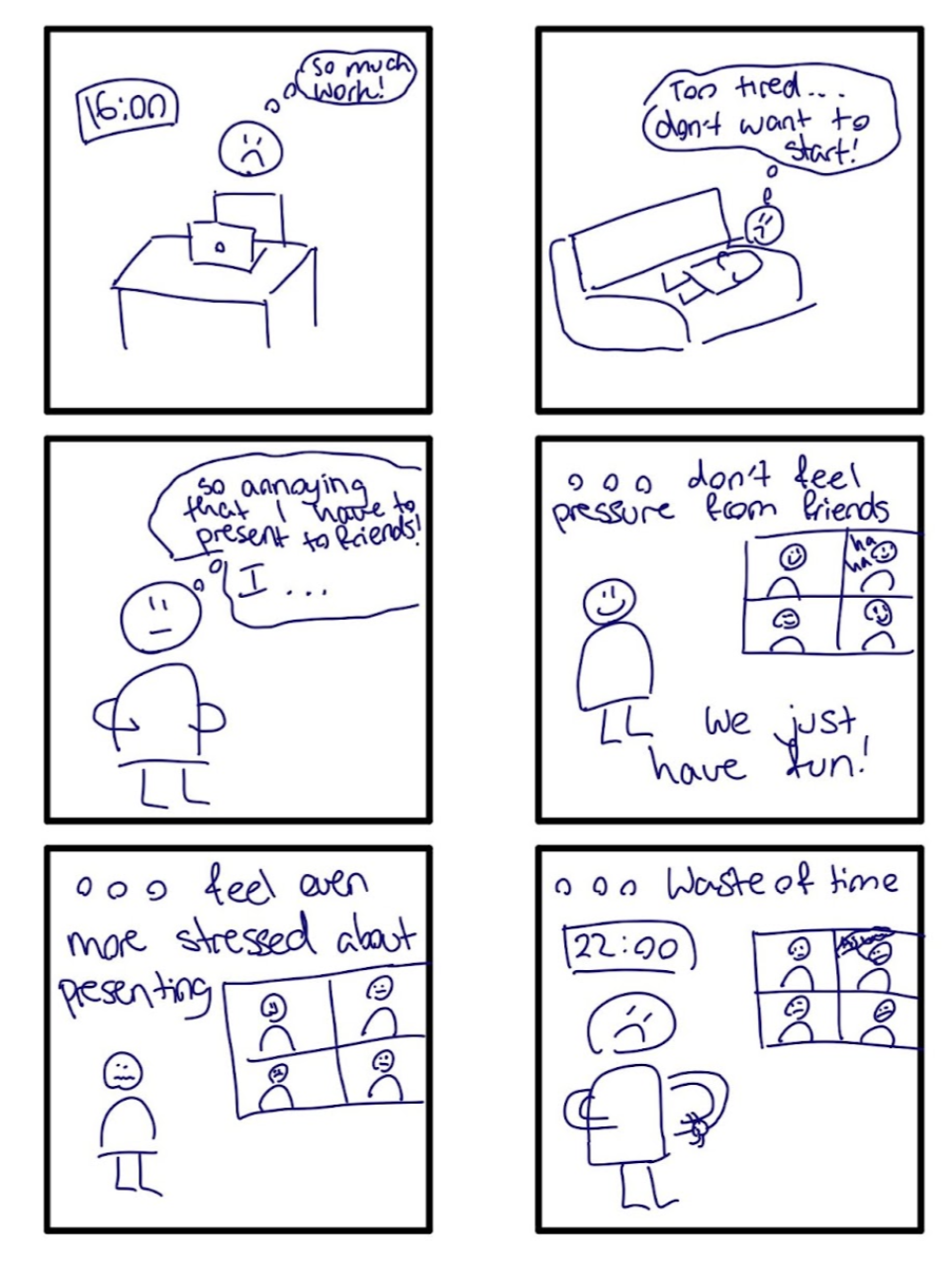

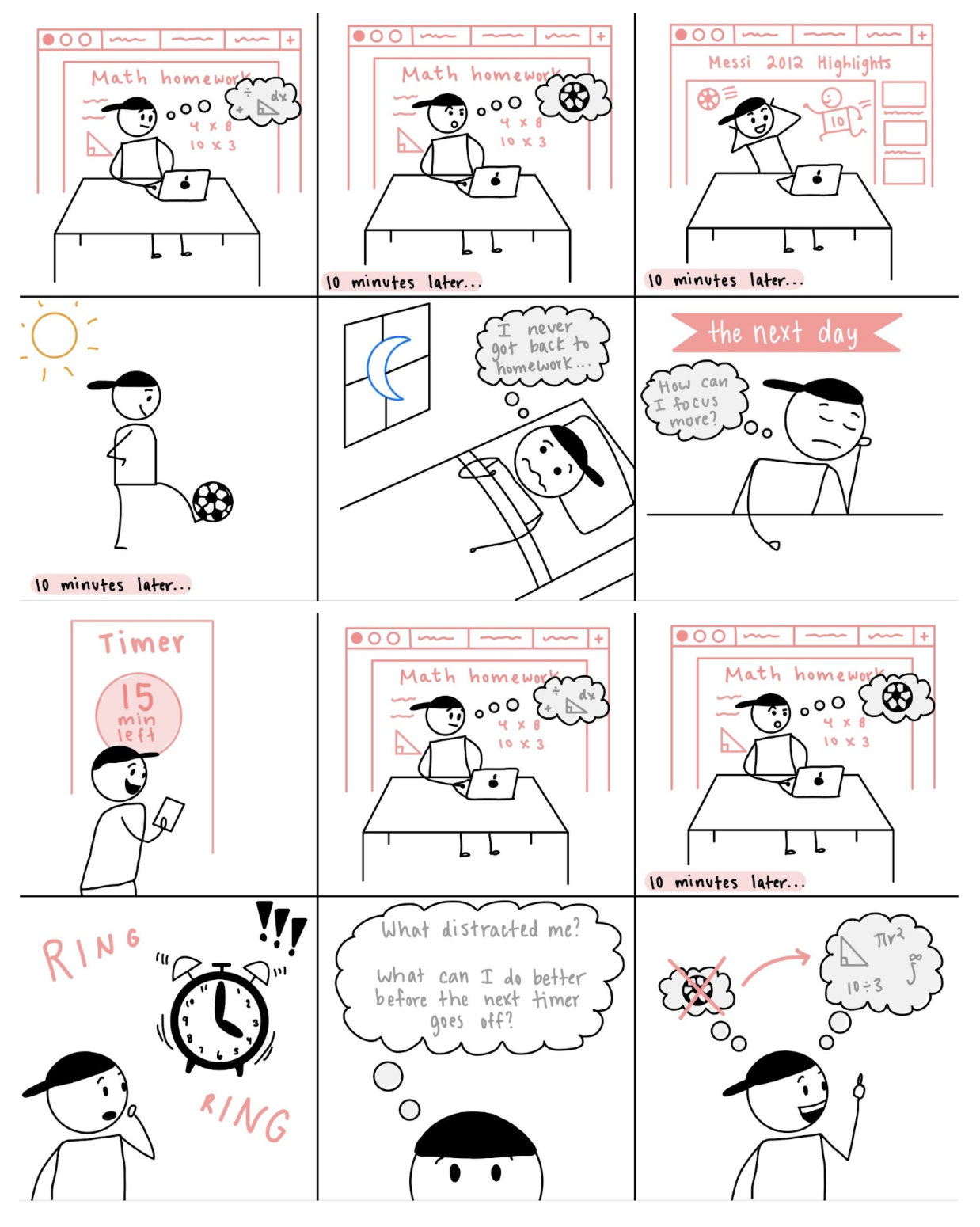

From there, we storyboarded our three selected intervention ideas: 1) a task splitter which takes in an assignment, creates more attainable sub-assignments, and offers a gamified or social angle to approach the sub-tasks from, 2) a daily presentation with friends at the end of the day, presenting work to one’s peers to create an artificial deadline and external motivation, and 3) an awareness chime or alarm which re-focuses users on their task or makes them aware of their distraction.

Storyboards:

1)

2)

3)

We shared these storyboards with our peers during class and received lots of feedback, as well as the pros and cons of each intervention. Regarding the first intervention, the students found that it would be extremely useful and helpful to see a broken down compartmentalization of the tasks at hand, but thought that it would be difficult to do so accurately as a third-party. With regards to the second solution, students found that the external accountability would be helpful, but that it came with a lot of negatives. For instance, users would have to take time out of their busy day to present and watch the presentations of others, and felt that their friends would not serve as sufficient external pressure. With regards to the third intervention, many resonated with the idea of setting regular checkpoint alarms and expressed they know people who do so, and find it effective. The con consideration is that it may be invasive to work sessions, however, it serves as an overall positive contribution.

We circled back with our team on the feedback we received, and deliberated for a while on the positive and negative attributes of our solution. We also reconsidered the problem we are trying to solve: should we reduce the barrier to getting started on work, or facilitating focus while already working. The latter seemed to be a larger need that we identified in our baseline study, and so we decided to create a singular, targeted solution.

First, we created storyboards as to why our non-selected solutions would not work, and the problems they posed:

#1 Revised Storyboard (why we did not select this solution)

#2 Revised Storyboard (why we did not select this solution)

Further, we revised our storyboard for the selected solution.

#3 Revised Storyboard (12 slides)

Intervention Study

After much deliberation, we wanted to devise an intervention study that is extremely simple and will be informative as to whether our potential solutions may be feasible and useful. Thus, we first defined our goal. We want to devise a consistent mindfulness/awareness check that forces users to instantaneously reflect on what they were/are doing. We found, in our baseline study, that students loved to see the difference between their predicted task duration and their actual task duration. It was an activity that brought their level of distraction into perspective. Thus, we recognized that students liked a form of reflection, and felt that it made them more aware in future work sessions.

For the intervention purposes, we decided to make the sound more accessible for all our participants by asking them to merely use their phone alarm. For the intervention, we will ask that the users either set a timer for 30 minutes or 1 hour (whichever is more relevant to their work content). They will also place a new sticky note each day on their laptop or desk, wherever they are working. Each time the timer goes off, they must log down whether they were focused or not, and if not, one word about the source of distraction. They will then share these daily sticky notes with our team. The goal is that each day, the participant will have a view of their focus levels and distractions throughout the work sessions.

Through our baseline study, we found that high school students in different geographies and schooling systems naturally experienced drastically different assignments, and in turn, work styles. Thus, we maintain that it is essential for us to gather a somewhat holistic picture of high school life and schedules, and will seek to recruit high school students in the US, Asia, and Europe. We have reached out to students who are siblings of friends, those we mentored or offered tutoring services to in the past, admin of local schools and our own former schools, and various contacts to recruit first and second degree connections. Some individuals who participated in our baseline study, and expressed special appreciation for the daily journaling activity, will also take part in our intervention as well.

The key questions we are striving to address in the study include:

- Will students appreciate seeing their focus levels through work sessions?

- Will these reflections enable students to improve their focus levels and reduce distractions over time?

- Are timers effective methods to refocus or do they distract further?

- Will students focus back on their task if they become aware that they are distracted?