Assumption Map & Tests

Here, we share how our assumption map guided our choice of the most crucial assumptions, the tests we ran to validate or invalidate them, and how each of our takeaways will inform future design opportunities.

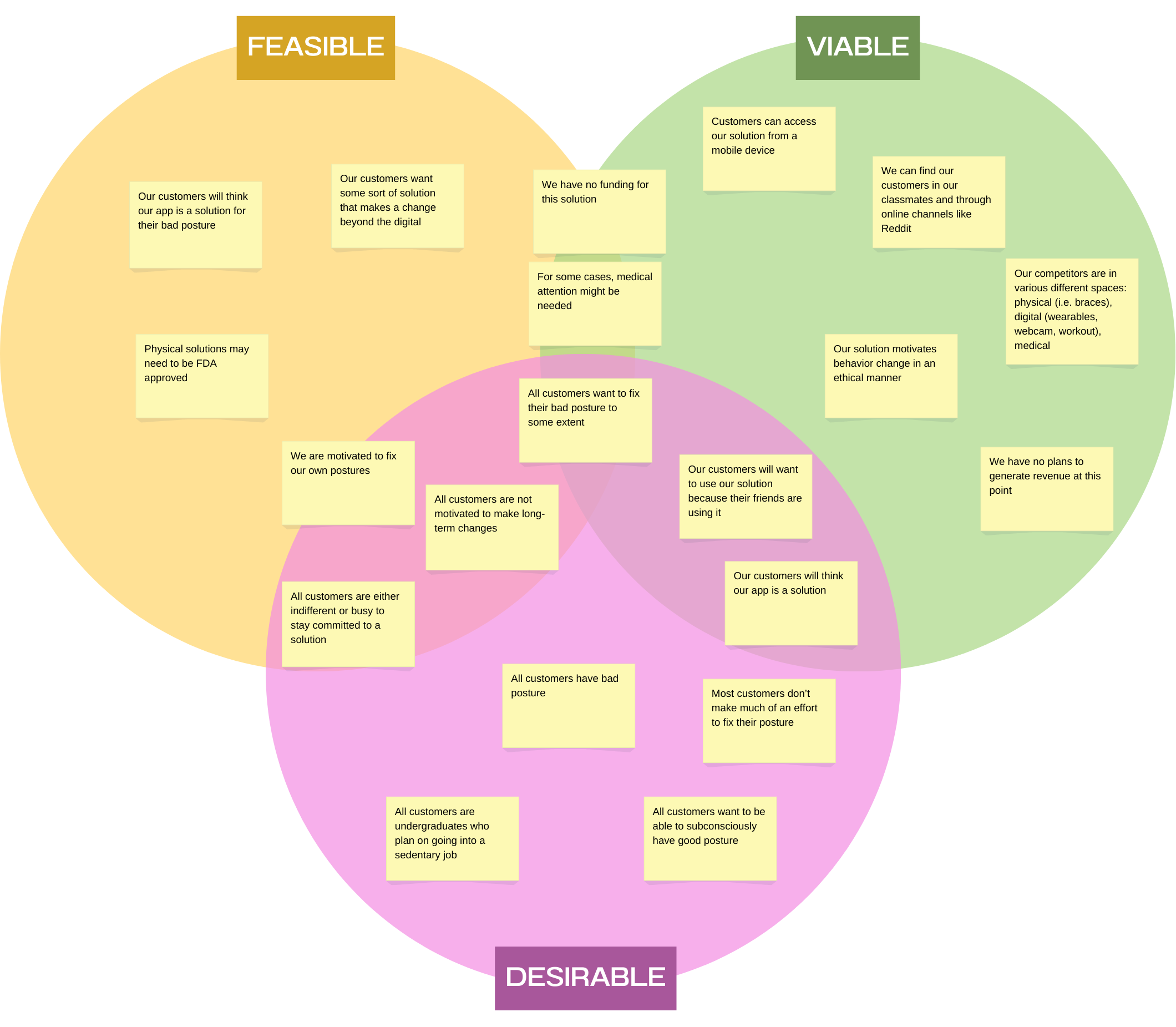

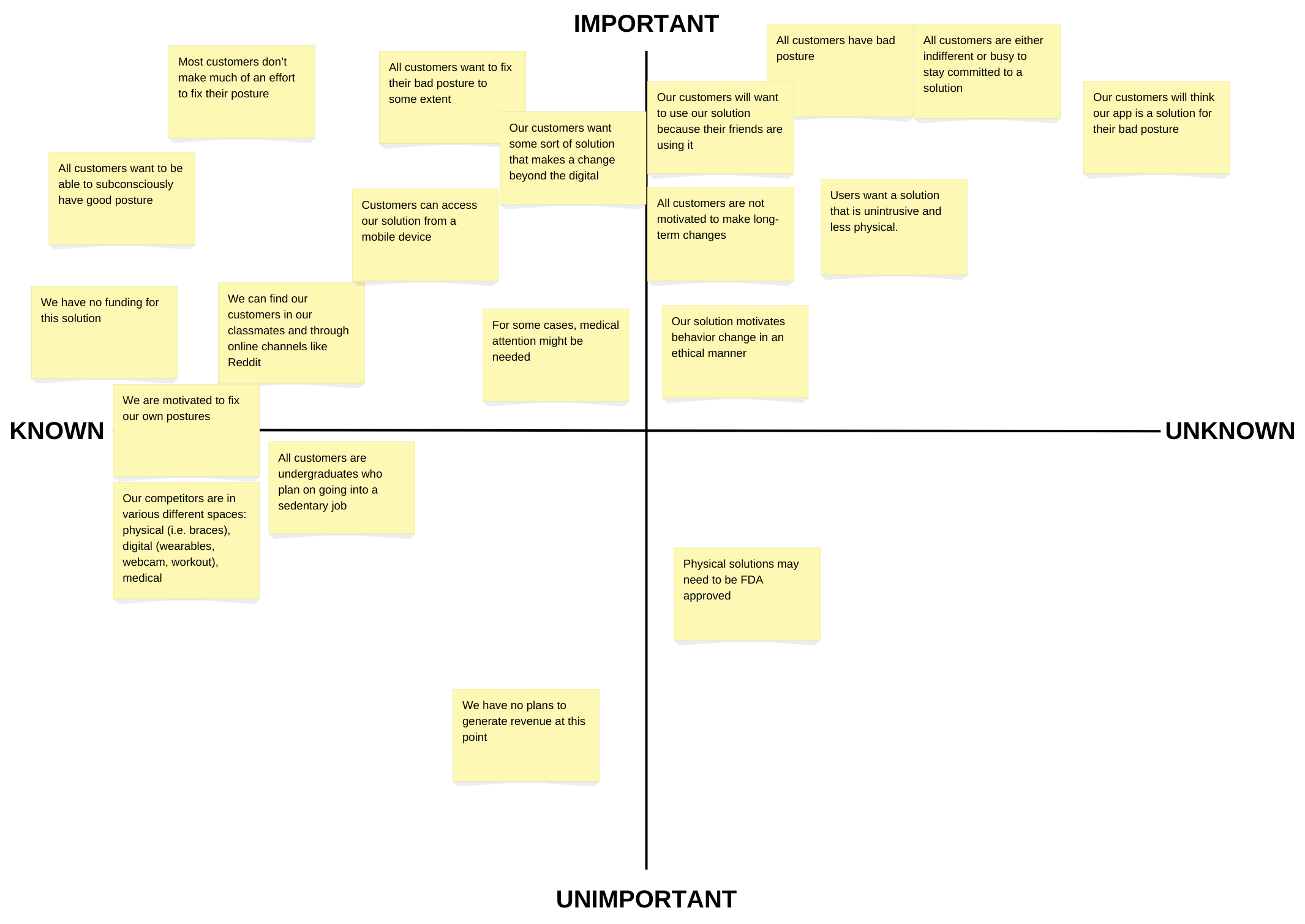

Highlighted Assumption Map and Quadrant

From our assumption map (linked here), we gained insights into how people perceive their posture habits and how they might want to adjust them. We observed various assumptions about motivations, and technical logistics—factors that shape whether or not a posture‐improvement solution will integrate into users’ daily routines.

As we refined these assumptions, some were moved into the “important and unknown” quadrant, giving us a more concrete basis for testing.

What We Learned So Far

We included this assumption map because it helped us visually organize and prioritize assumptions about user motivations, technical logistics, and the feasibility/viability/desirability of various posture-improvement solutions. The structure of the map made it clear which assumptions are “important and unknown,” which guided our focus on the three assumptions below. In turn, these assumptions most strongly affect whether or not our product can fit seamlessly into daily routines

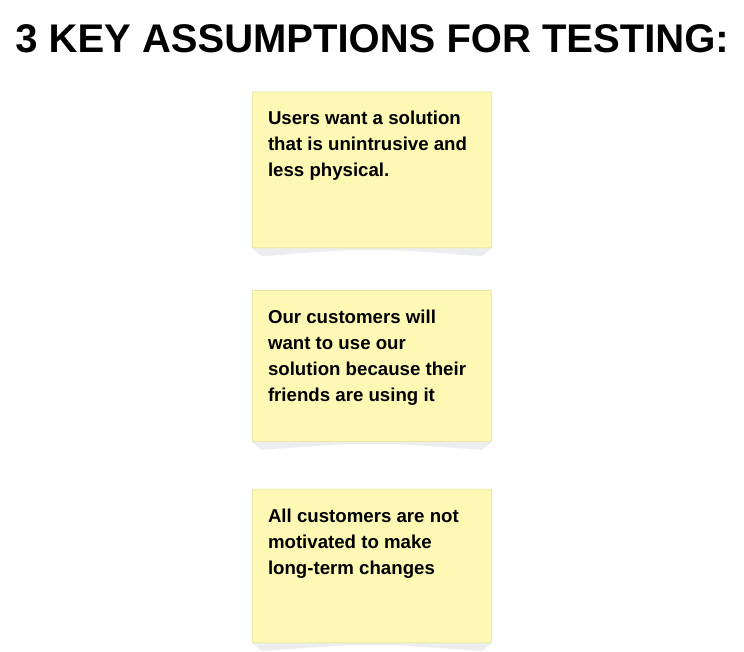

Most Important Assumptions (from Our Assumption Map)

Below are the three assumptions we chose to test(using the below test card as guidance), presented below:

- ASSUMPTION 1

Hypothesis: We believe that the users want a solution that is unintrusive and less physical.

Test: To verify that, we will show them the range of existing solutions and ask them to rank which ones they prefer and explain why.

Metric: And measure the rankings.

Criteria: We are right if they prefer digital or less intrusive solutions over more intrusive ones (i.e. chiropractors, braces, etc.)

- ASSUMPTION 2

Hypothesis: We believe that our customers will want to use our solution because their friends are using it.

Test: To verify that, we will share two fake products, where on the sign-up page it says either that some of their friends are using it/referred the app or a sign up page that doesn’t include this information. Have them rank how willing they are on a scale of 1-5 to sign up for the app.

Metric: And measure which one has a higher average ranking.

Criteria: We are right if the one with information on friends gets a higher ranking.

- ASSUMPTION 3

Hypothesis: We believe that all customers are not motivated to make long-term changes.

Test: To verify that, we will provide two hypothetical solutions that cost the same amount of money, but one is a one-time payment that guarantees results in a year and the other is a monthly subscription (but same price over the course of a year) that also guarantees perfect posture by the end of one year.

Metric: And measure the number of votes each solution gets (start with just a one month subscription or just buy the long-term solution).

Criteria: We are right if more people vote to get a one-month subscription.

Insights

Here are some key insights drawn from working on our assumption map:

- One of the most clear takeaways from our analysis is that people may not want to wear bulky or invasive devices which may communicate a low tolerance for physical inconvenience.

- It is also important that we keep at the forefront, solutions they can integrate into existing routines without adding too much friction(and risking user motivation dropping off at record speed).

- For posture, which is an inherently personal behavior, peer and social influence could be a potentially strong ally if it’s framed in the right way.

- Even when people say they want better posture, they may often lack the persistence to do what will create change.

- We may need to leverage some habit formation strategies to keep the staying power of our future intervention.

Detailed Assumption Test Experiment Design

We designed these specific tests to isolate our critical assumptions (intrusiveness, social influence, and motivation for long-term change) because our prior needfinding and literature review indicated that these three factors consistently determine the success of posture-improvement solutions. By focusing on these, we can gather direct feedback that tells us how each factor shapes user adoption

Assumption Test #1:

Present interviewee with a Google Form of the following to-be-ranked products:

- Tracking app

- Wearable reminder that buzzes every minute

- Ultra thin back brace

- Chiropractic visits (in person)

Statements should be ranked on a scale from 1-4 based on posture improvement solutions that they would most prefer, with 1 being most likely, and 4 being least likely.

Interviewee proceeds to describe, in words, why they picked their top option.

Finally, interviewee ranks 6 factors of what matters most to them for a solution from the following:

- Convenience

- Cost

- Comfort

- Minimal physical equipment

- Professional support

- Easily added to daily routine

Interviewee ranks them from 1 (being the most important factor) to 6 (being the least important factor).

Based on our research, there are four domains of solutions: physical and intrusive, physical and unintrusive, digital and intrusive, and digital and unintrusive. We chose a solution for each category with the following matches:

- Tracking app – digital and unintrusive

- Wearable reminder that buzzes every minute – digital and intrusive

- Ultra thin back brace – physical and unintrusive

- Chiropractic visits (in person) – physical and intrusive

As a result, the first question aims to investigate which category of solution is most preferred by customers. If the average ranking of the digital and unintrusive solution is higher (and preferably the highest) compared to a physical and intrusive solution, we will know our assumption is correct.

Additionally, the questions asking about why an option is their favorite pick will help us glean further insights as to why they picked a particular solution. This was specifically done in order to determine if they mention the digital/physical or intrusive/unintrusive scales. If they do, we can weigh these answers more heavily and be confident in our assessment of which type of product is most preferred.

Finally, the questions asking the participant for a ranking of important factors for a solution, allows us to understand what is most important in a solution for the participant. By analyzing which factors are most highly rated on average, we are able to determine which factors matter most to participants. If they highlight a factor like “convenience” or “minimal physical equipment”, it will help us better understand where the solutions fall along the axes.

Assumption Test #2:

Present interviewee with a Google Form with the following proposed scenario:

Let’s say you have found two apps to fix your posture! The first one is an app that was recommended to you by 5 of your friends who are using it and the other app was one that you found on your own, but seems like it would be effective from the research you did.

Have the interviewee rank each solution based on how likely they are to get the app, with 1 being very unlikely and 5 being very likely.

Pose the interviewee with a follow up question asking them whether they prefer an app they found themselves or recommended by friends for a health and wellness app, or if they have no particular preference.

Third, ask the interviewee the following question:

Imagine you’re deciding between two posture improvement products that are equally effective. Which of the following would most likely influence your choice (choose up to 2)?

The options they can select from should be as follows:

- Personal research and reviews

- Friends or family using the product

- Expert/professional advice

- Brand reputation

- Price difference

- I’d choose randomly if all other factors are equal

The first question was chosen to understand what type of posture related app our audience would prefer and if they would be more likely to use an app that their friends are using to test our assumption. If there is a higher average rating for the app recommended by friends, we will know our assumption was right. The second question, similarly, asks people if they have a direct preference in case our last question didn’t make it clear enough. If more people have a clear preference for an app recommended by friends, we will know our assumption is correct.

The final question aims to understand what factors most influence an individual’s decision to choose a particular product. This question was chosen because our underlying assumption was made to best understand how to drive customers to use a product. As a result, if we understand other similar factors, we can incorporate those into our solution. The factors with the most votes are indicative of the factors that users most care about in their solution and we want to make note of and make sure to implement them in our final product.

Assumption Test #3:

Present the interviewee with a Google Form of the following proposed scenario:

Let’s say you have found two products that are both equally effective and can fix your posture permanently in one year. The first one costs $144 up-front for the whole solution. The second one is based on a monthly subscription, and costs $12 per month (meaning by the end of the year, you will have paid $144 for that product as well).

Have the interviewee select the solution that they would prefer and briefly explain what led them to that preference.

Follow up by asking the interviewee if they have ever tried to improve their posture, and if yes, have them select which methods they have tried.

Lastly, ask the interviewee how long they consistently maintained the habit, with the options less than 1 month, 1-3 months, 3-6 months, 6 months-1 year, and over 1 year.

The first question was chosen to understand whether the interviewee would prefer a solution that requires a year-long commitment (due to the up-front cost of $144), or a solution that allows them to pay monthly and the ability to walk away ($12 each month, adds to the same $144 yearly). Additionally, it tries to understand better why the interviewee preferred the solution they selected. If more people prefer the monthly subscription solution because they want the option to save money and cancel the subscription, we know our assumption is correct. The second and third questions were asked to see if people have tried to fix their posture before and how long they were able to maintain that commitment. If the majority of people who tried to fix their posture only sustained the habit for a few months or less, we know our assumption is correct. Looking at the responses to the methods that people have tried in the past, we can better design our solution to address problems with past tried solutions.

Assumption Test Recruitment Process

Our project focuses on the bad habit of bad posture. From our needfinding interviews, we realized that most undergraduate students spend a lot of time sitting down and in front of their devices. In addition, these students are busy and are constantly in the presence of other people. Based on our assumptions, it made sense for us to recruit people who know a lot of people/are pretty social, and have packed schedules (i.e. do research, go to the gym, go to club meetings, etc. in addition to class). Busy students should have a harder time keeping themselves in check with their posture, therefore being unable to commit to any long-term solutions and social students might be more easily influenced by their friends’ opinions. In addition, both student groups should want a solution for their bad posture that would not arouse any sort of attention, yet help them mindlessly.

Experiment Data

How These Results Build on Our Previous Work

In earlier stages, we identified recurring themes around user convenience, social influence, and difficulty with sustaining posture improvement efforts. Our assumption map helped us focus on these key points. The following learning cards show how each experiment’s outcome either confirmed or refuted these assumptions.

Learning Cards

LEARNING CARD FOR ASSUMPTION 1

Opportunities for Intervention

Since users prioritize minimal disruptions, any future product design should be built around seamless integration. For example, a smartphone app that works passively in the background could reinforce posture checks without adding an extra physical device. This aligns with our goal of remaining as unobtrusive as possible.

LEARNING CARD FOR ASSUMPTION 2

Learning and Insights

From that we learned that while friend recommendations received a higher rating compared to self discovery, personal research and expert opinions were equally influential, which suggests that users do not rely solely on their social circles for decision-making. Our results show that the popularity of a product among user’s social groups does matter a moderate amount (14.3% higher likelihood), but there might be other factors that are equally as powerful in terms of influencing a user to adopt a product.

Opportunities for Intervention

By embedding social features—such as group challenges, friend leaderboards, or easy ways to share posture progress—we can leverage peer influence while still respecting that users also value professional/expert endorsements. Incorporating reliable research or expert validation alongside social sharing could further encourage adoption

LEARNING CARD FOR ASSUMPTION 3

Learning and Insights

From that, we learned that users prefer a solution that will give them the option to easily walk away and not make a long-term commitment to solving their posture problem. We also learned that 5 of the 7 individuals have tried to fix their posture in the past, meaning that despite their reluctance to engage in long-term solutions, most participants (5 out of 7) express a desire to improve their posture.

Opportunities for Intervention

A flexible subscription model or “freemium” approach could help users try the solution without committing for a full year upfront. This lowers barriers for long-term adoption, acknowledging that many users have tried posture fixes but did not maintain them beyond a few months. Gradually building trust and demonstrating effectiveness may help transition them to a more sustained plan.

Through our assumption testing, we validated that intrusiveness, social influence, and long-term commitment are pivotal factors shaping the adoption of posture-improvement solutions. By focusing on a minimally invasive, socially supported, and flexible model, we plan to prototype a digital intervention that addresses these needs. In the next phase of our study, we used these assumptions to implement an intervention.

Intervention Study

How did your intervention study go?

Our intervention study was moderately successful as it provided valuable insights into how group observation and accountability influence posture awareness and improvement. The participants of the study actively engaged in monitoring other peers’ posture, and the process encouraged self-awareness. Many participants expressed they were more mindful of their own posture when they were actively observing someone else’s, suggesting that social accountability might not only raise awareness but also trigger self-regulation.

However, while this study demonstrated that social factors influence posture habits, we noticed that challenges arose in tracking consistency and effectiveness. Some participants found it hard to track in 15-minute increments, and a lack of real time feedback made change difficult to consistently incorporate.

What did you learn?

Below are some of the key insights that we learned through this intervention study:

- Social Influence Matters – Participants seemed to adjust their own posture when reminded to check someone else’s, showing that the act of observing someone else actually serves as a posture intervention.

- Consistently Tracking is Difficult – Some participants/observers noted that tracking an individual in 15-minute intervals or 15 minute periods throughout the day was difficult and that a more automated or structured approach is needed.

- Real-time Feedback is Needed – Posture ratings were logged some time after the observations occurred, which proved to be less effective than a wearable device that buzzes, prompting good posture immediately.

- Awareness of Being Tracked Changes Behavior – After participants were told that their posture was being tracked and compared to their friends, many of them adjusted their posture more frequently, especially when they were around their fellow posture group members. This suggests that social competition and awareness of comparison can be effective motivators for improving posture.

Discuss how the study was to be conducted, who was recruited, and the key question(s) being addressed by the study.

Study Setup: Participants were recruited in groups of 2-3 and assigned to observe a peer in their group’s posture for a total of one hour a day, logging posture ratings at 15-minute intervals throughout the day. Specifically, we had one group of two and one group of 3 for a total of 5 participants. The study was conducted over four consecutive days. Participants were asked to rate their friends’ posture from the following options: Strongly Upright, Moderately Upright, Neutral, Moderately Slouched, or Strongly Slouched. Each participant was also aware that their posture was being tracked and compared to their friends about halfway through the study.

Recruitment: The study included university students who engaged in daily activities involving varied postures, such as studying, socializing, exercising, eating, etc. We specifically chose groups of friends that would consistently see each other at least 4 times during a 4 day period. All of our participants had not previously participated in any of our studies, so they had no prior knowledge about our project.

Key Research Questions:

- Does social accountability improve posture habits?

- Do participants become more aware of their posture while observing others?

- Will participants change their posture behavior after being aware that they are being tracked and compared to their friends?

Key insights from the intervention study

- Peer observation alone does not greatly influence habit change – The format of peer observation raised awareness of individual posture, but without real-time feedback, many participants did not adjust their posture.

- Social Accountability is Powerful – Many participants noted that their posture was improved just by knowing that they were being observed at some point. Additionally, many noted that checking a friend’s posture helped them be more aware of their own posture.

- Comparison and Awareness Drives Action – After participants were explicitly told that their posture was being tracked and compared to their friends’ postures, they were more likely to adjust their posture when in group settings. This indicates that awareness of social comparison can be a strong motivator for behavior change.

Opportunities for Intervention

Based on our intervention study, our solution – an application that utilizes social accountability through a wearable posture tracker and group scores – needs to emphasize the following:

- Real-Time Posture Feedback – Instead of manual logging, the wearable needs to provide instant feedback through notifications or buzz alerts when poor posture is detected

- Gamification with Progressive Goals – Instead of just penalizing bad posture, our application should include rewards and incentives to make the experience more engaging, desirable, and sustainable.

- Enhanced Group Interaction – Since social accountability proved to be so effective, the app should allow users to nudge and encourage their friends, provide positive reinforcement, and show metrics that track group performance toward goals and rewards.

- Comparison Features to Encourage Better Posture – Since awareness of tracking and peer comparison increased posture improvements, the app could incorporate elements such as leaderboards, shared progress updates (including being able to see other group members doing well), and recognition of users that achieve a goal to further encourage better posture habits.

Our intervention study highlights key factors that influence posture awareness and behavior change, emphasizing the importance of real-time feedback, social accountability, and structured tracking. These insights will shape the way we refine our solution and ensure that it aligns with the behavioral patterns we observed in participants.

To translate these findings into a user experience, we can explore system paths. Our system paths will outline how different personas interact with the app, particularly how individuals like Valeria, a proactive user, would discover, onboard, and integrate her friends into the experience. In the following section, we detail the main user flows that define our solution based on insights from our intervention study, showing how our app facilitates posture improvement through social dynamics and gamification.

System Path

Process

We began by considering our different personas and the exact steps of how they might be introduced to the app. We decided that one persona, Valeria, would be the one who is most likely to discover the app and get her friends to join her. From here, we went through all the stages that she would be involved in, including onboarding, creating a group and inviting friends, and using the app with rewards. From there, we considered where the other group members would join in (particularly at what stage) and what parts of the process they would skip (such as inviting other friends). This led us to create an overall pipeline for all the personas and we were able to highlight the main cycle in the app that doesn’t include the onboarding.

Why a System Path

The system path helped us spot gaps in our understanding (e.g., where social accountability or professional recommendations come into play) and served as a foundation for designing our intervention study.

Insights from the System Path

We paid special attention to potential social interactions, points of friction (e.g., cost or inconvenience), and triggers for re-engagement.

- Social Influence: Jacob relies heavily on friends’ recommendations, while Valeria is more research-driven. Cheban cares about social proof(does not care otherwise, until he feels left out) but also needs convenience due to his busy schedule.

- Reusability of Features: Many steps, such as “download an app” or “get real-time posture reminders,” appear across all personas, suggesting we can design features that benefit everyone but still allow for personalization.

- Motivation: All our personas show a tendency to drop off if the solution is too intrusive or if they don’t see quick benefits.

- Opportunities for Social Accountability: Our path highlighted that social or group-based strategies might keep certain users (like Jacob and Cheban) engaged longer even without enough intrinsic motivation.

Opportunities for Intervention

Different personas respond to different motivators (social pressure, professional advice, convenience). Given these insights from our system path, we designed an Intervention Study to test whether group accountability and social rewards can motivate users to improve their posture over a short period. We focused on group dynamics because the system path revealed that social influence was a recurring theme for multiple personas. We also integrated the idea of quick feedback (e.g., observation scoring) because our system path showed that users need immediate reinforcement to stay engaged.

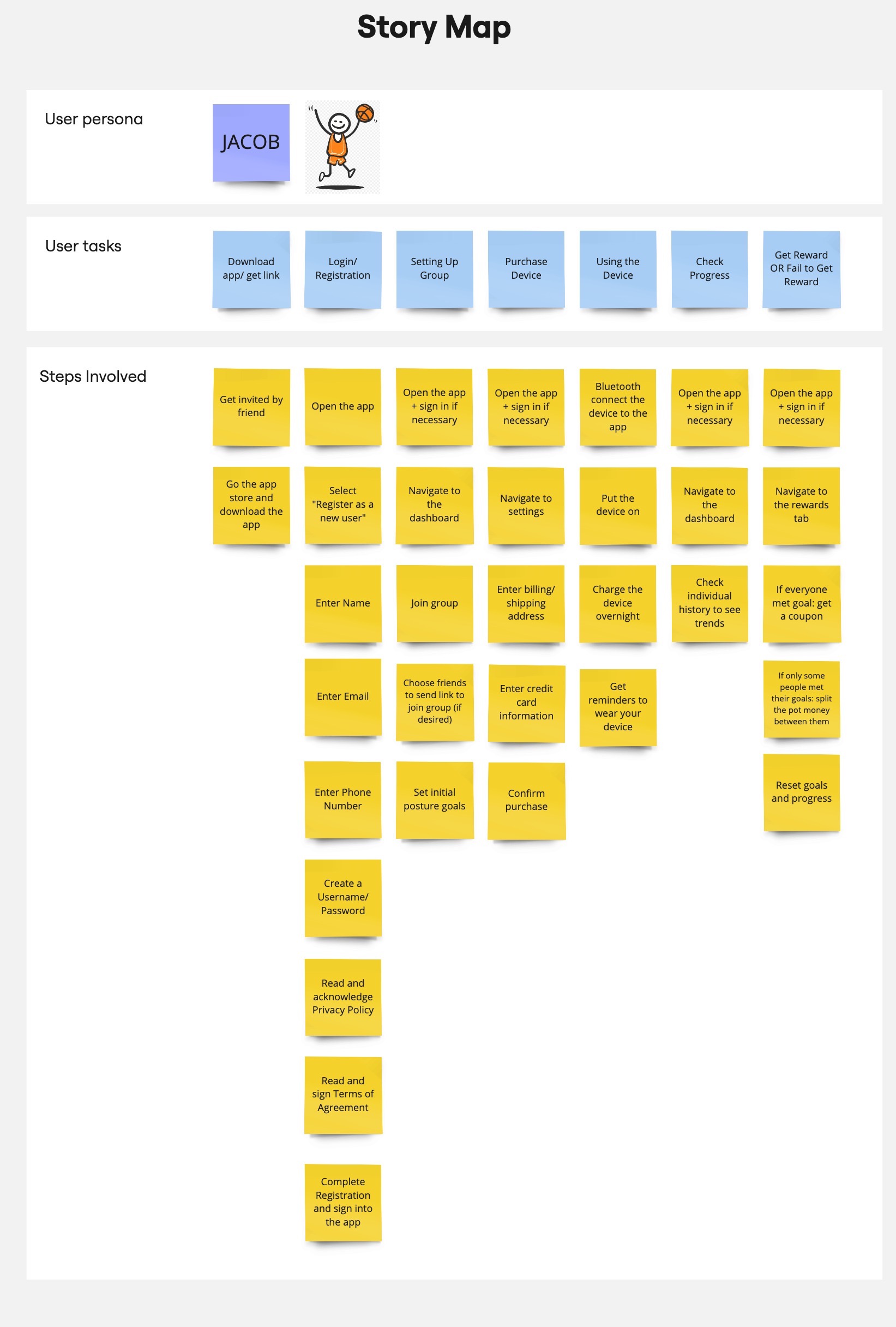

From the system path, we’re able to see a general flow of how our app works and how different personas are involved. However, we want to really zoom in on an individual persona and break down these tasks as much as we can to understand the process in depth. Let’s take a look at a story map for our persona for Jacob.

Story Map

Process

We began by considering our different personas and the exact steps of how they might be introduced to the app. We decided that one persona, Valeria, would be the one who is most likely to discover the app and get her friends to join her. From here, we went through all the stages that she would be involved in, including onboarding, creating a group and inviting friends, and using the app with rewards. From there, we considered where the other group members would join in (particularly at what stage) and what parts of the process they would skip (such as inviting other friends). This led us to create an overall pipeline for all the personas and we were able to highlight the main cycle in the app that doesn’t include the onboarding.

Why a System Path

The system path helped us spot gaps in our understanding (e.g., where social accountability or professional recommendations come into play) and served as a foundation for designing our intervention study.

Insights from the System Path

We paid special attention to potential social interactions, points of friction (e.g., cost or inconvenience), and triggers for re-engagement.

- Social Influence: Jacob relies heavily on friends’ recommendations, while Valeria is more research-driven. Cheban cares about social proof(does not care otherwise, until he feels left out) but also needs convenience due to his busy schedule.

- Reusability of Features: Many steps, such as “download an app” or “get real-time posture reminders,” appear across all personas, suggesting we can design features that benefit everyone but still allow for personalization.

- Motivation: All our personas show a tendency to drop off if the solution is too intrusive or if they don’t see quick benefits.

- Opportunities for Social Accountability: Our path highlighted that social or group-based strategies might keep certain users (like Jacob and Cheban) engaged longer even without enough intrinsic motivation.

Opportunities for Intervention

Different personas respond to different motivators (social pressure, professional advice, convenience). Given these insights from our system path, we designed an Intervention Study to test whether group accountability and social rewards can motivate users to improve their posture over a short period. We focused on group dynamics because the system path revealed that social influence was a recurring theme for multiple personas. We also integrated the idea of quick feedback (e.g., observation scoring) because our system path showed that users need immediate reinforcement to stay engaged.

From the system path, we’re able to see a general flow of how our app works and how different personas are involved. However, we want to really zoom in on an individual persona and break down these tasks as much as we can to understand the process in depth. Let’s take a look at a story map for our persona for Jacob.

MVP Features

- Login/Registration

- Username/Password

- Invite Friends

- Create a group

- Be able to send a link to friends

- Join a group

- Purchase Device

- Billing/shipping address

- Credit card information

- Putting Device On

- Bluetooth connect the device to the app

- Charge overnight

- Check Progress

- Open the app and get to dashboard, which displays point counts

- Reward

- If everyone wins: coupon to get a meal!

- Else: people who met their goals get the pot money

Our story maps and sketching out the features of the MVP helped us gain a key understanding of the system of our solution and what we hope to accomplish. We then wanted to understand the different pieces of our solution and how they all interact with one another to better understand the structure as opposed to just the individual needs of our solution. To address this, we created a bubble map.

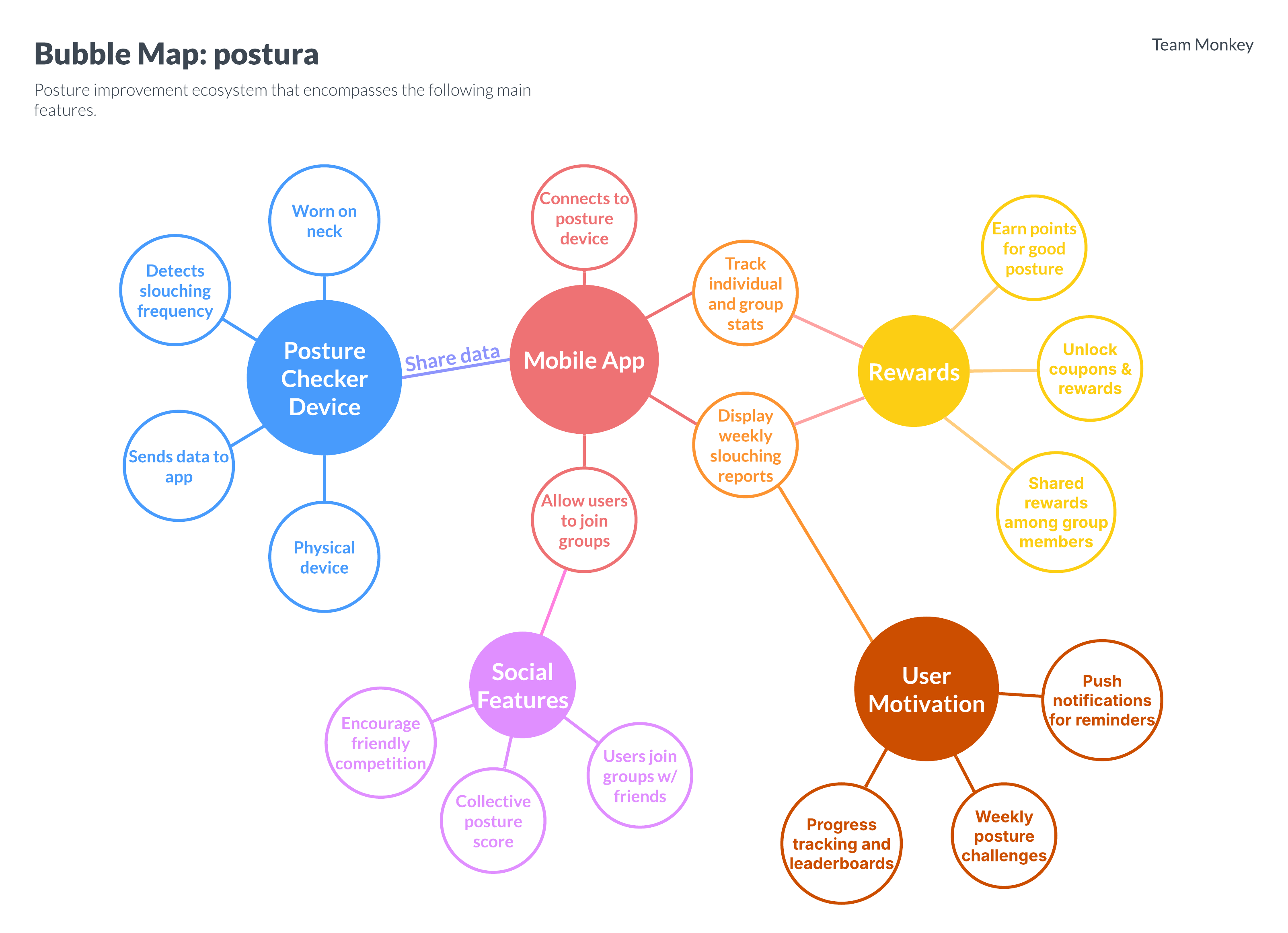

Bubble Map

Model Choice and Why:

After our study, we realized that we could not rely solely on a physical device to remind others or an application that relies solely on self-motivation to keep up good posture. This behavior would not be sustainable and we would not be able to make good posture a habit. We also could not avoid the application. As a result, our solution encompasses the two main components explained previously: a mobile application and a physical posture checker device.

The posture checker device on its own has some very simple functionality and purpose: have the user put it on the back of their neck throughout the day and report posture data back to the app. The device does not shock the user or indicate to them to improve their posture in order to not disrupt or disturb their everyday life. Nevertheless, this is a critical component because the application would not be able to work without this data.

On the other hand, the mobile application is what carries the majority of the functionality of this service. Using the posture checker device’s data, we can calculate a score of the week for the user. However, to make sure that the person actually cares about these statistics, we have them join with a group so they all work toward a group weekly goal – this encompasses the social feature of the app. In order for this to be even more effective in changing behavior, we introduce the concept of rewards where groups can earn certain rewards – whether it be coupons or such – that they can share and use as collective reward. In order to motivate our users, we make sure that their posture statistics are readily available and we send reminders for them to realize that they might be slouching or that they need to work harder to reach their weekly goal.

Doing this bubble map helped us realize what our service really stands for and what we can offer to our users. Our main app will rely on social components, rewards, and user motivation. Those are our core values. All we have to do for our MVP, is to stick to these values and find a way to portray them visually that will get others interested in joining the app.

Opportunities for This Intervention:

Workplace Wellness Programs – Many companies are looking for ways to improve employee well-being. Integrating this system into corporate wellness programs can encourage employees to maintain better posture and reduce health risks related to prolonged sitting.

Partnerships with Health and Fitness Brands – Collaborations with ergonomic furniture companies, fitness apps, and physical therapy services can enhance user engagement and offer complementary solutions.

Gamification and Community Engagement – Expanding on the social aspect by introducing leaderboards, team challenges, and personalized coaching can increase user retention and motivation.

Educational Institutions – Schools and universities can promote the device to encourage students to develop good posture habits early, especially given the rise of screen-based learning.