Table of Contents

Assumption Map + Tests

Assumption Mapping

Link to the original assumption mapping post here.

Our assumption map revealed nuances in the ways people perceive their social media use and how they might want to adjust their usage habits. We observed various assumptions about target demographic, desired app interactions, preferred behaviors (that would replace social media use), motivations, technical logistics, and competitors. As we discussed, some assumptions were refined into more detailed ones that either added them to the important and unknown quadrant or created a more concrete basis on which to test.

In comparison to other assumptions, we realized there were two key areas of questioning that were important to our solution:

- What kind of reward feedback do users want (to reinforce their desired change)? To what degree?

- How many customization and disruptive measure (against distracting social media use) features would users want for them to be effective?

Without these questions answered, our solution would struggle to distinguish itself from existing solutions and/or find its own niche. Answering these questions would help us understand what approach we wanted to take and what we wanted to convey to users. Thus, two of our assumptions (listed below) aimed to address these questions.

Additionally, one assumption was initially considered less important and uncertain compared to others. The assumption was that users want to engage with social media more sustainability, but our diary study interviews revealed varying attitudes toward its use. Understanding what users want to do instead of distracting social media habits became a very important insight and a potential pivot point for our project, and so we decided to explore it.

The three assumptions that we chose to test were:

- Users want to experience a sense of achievement as they work on reducing their social media use.

- Having high user customization ability regarding limitations/disruptive measures would be helpful

- Our users would rather be doing something else productive than being on social media

Assumption Tests

In the assumption tests, we explored how people interact with social media and tested different ways to help them manage their screen time. We focused on motivation-based rewards, concerns about productivity regarding social media use, and looking for more personalized interventions.

Participants for these tests were selected based on self-reported struggles with doom scrolling and excessive screen time use. The participants varied in work environments and habits, which helped us analyze the differences in social media usage and how it affects certain demographics.

Test 1: Achievement and Reward-Based Motivation

Hypothesis: Users want to experience a sense of achievement as they work on reducing their social media use.

The first study tested whether users feel more motivated to reduce screen time when they receive a reward for avoiding social media. To verify that, we tested different kinds of achievement/reward systems. We took notes about what systems users prefer choosing, and how they feel about receiving that type of reward feedback. Also, we assessed how they feel about the other types of feedback.

Through this, we measured users preferences regarding the intervention, effects on users behavior (which method led to more reduction in screen time), users emotional response, how did they feel after the intervention, and engagement & retention (are users planning on using the intervention or deleting the app).

A surprising finding was that negative reinforcement (such as forced log-offs or discouraging messages) was more effective than positive rewards. Users reported that guilt or consequences helped them stay off social media better than rewards alone. The results made us more conscious about how we might encourage positive reinforcement. They may still be valuable but may require additional reinforcement mechanisms (i.e. tangible rewards) to be perceived as equally effective. This could be addressed in an example such as this: every time the user tries to open social media, they can be reminded of a habit they enjoy, and if they choose it instead, they add to their habit jar, which is reinforcing positive behavior in a rewarding way.

Test 2: Productivity and Social Media Use

Hypothesis: Our users would rather be doing something else productive than being on social media

The second study explored whether users wished they were spending time on something more productive instead of using social media. Participants, corporate workers, freelancers, and startup employees, ranked statements about their social media habits and feelings of guilt or productivity loss. These ranked statements showed us their social media usage and if they feel guilty or productive after. Specifically, we looked into the role of social media in their lives, how they balance social media and work, the guilt associated with their usage, and which types of workers experience productivity loss the most.

Findings showed that corporate workers use social media to fill a social gap at work, freelancers see it as a major distraction, and startup employees have mixed feelings, using it both for networking and as a distraction. This suggests that different types of workers need different solutions to manage their screen time. These results suggest an opportunity for tailored screen time solutions based on work environments. For corporate workers, it could suggest alternative social engagement activities instead of social media. For freelancers, it could provide more focus required tasks to minimize distractions. By tailoring habit recommendations, the Good Habit Jar ensures interventions are relevant and effective across different work settings.

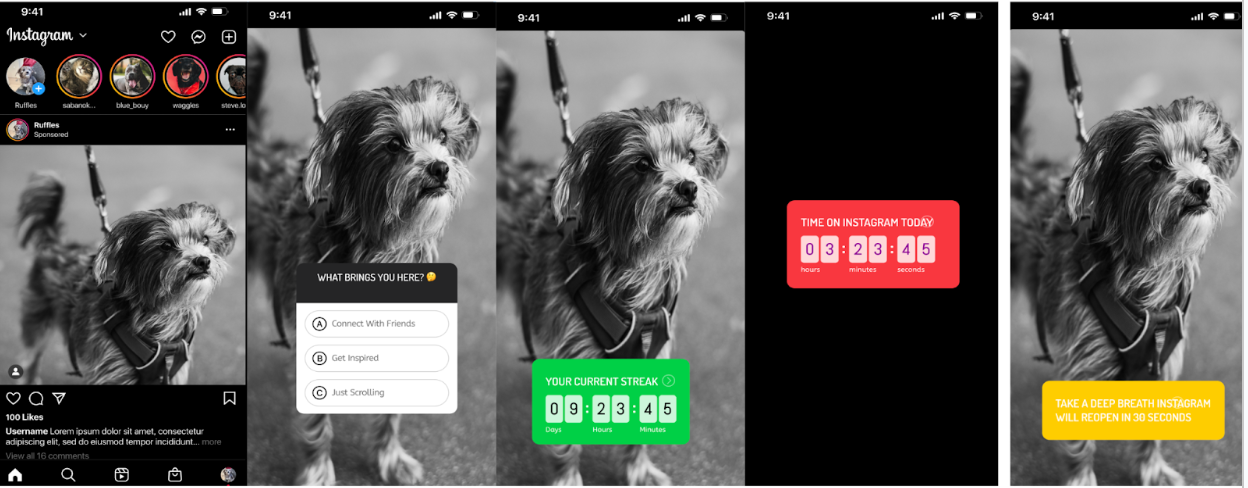

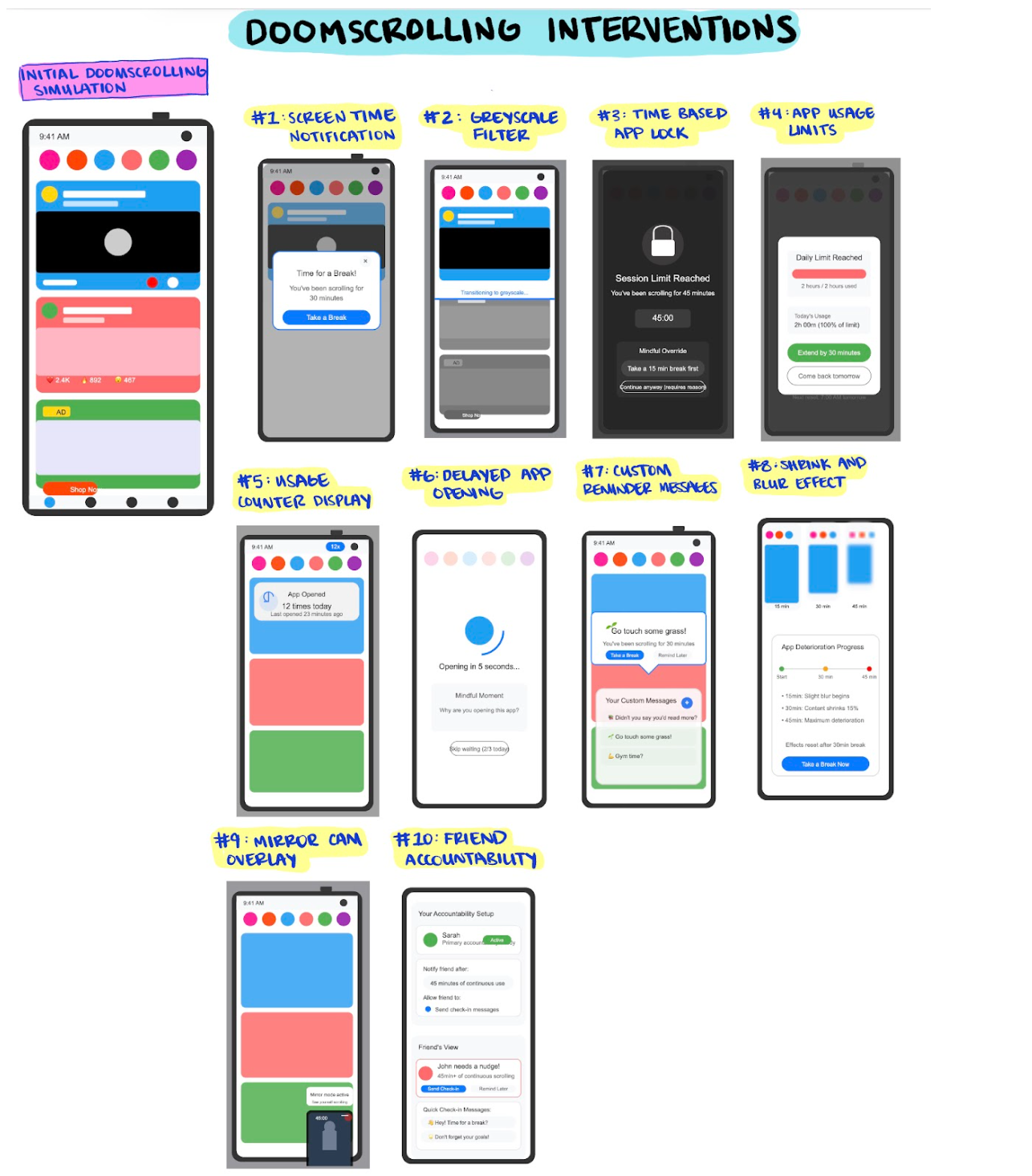

Test 3: Customizable Disruptive Measures

Hypothesis: Having high user customization ability regarding limitations/disruptive measures would be helpful

The last study tested whether giving users control over their own screen time limits would help them engage more with intervention tools. Participants were offered different options, such as:

- Time limits and reminders

- Grayscale filters to make apps less appealing

- Friend notifications for accountability

- Custom options they could create themselves

One by one, participants were shown visual representations of different interventions, each designed to disrupt excessive screen usage. After selecting their desired methods, participants described:

- How they expect to encounter these disruptions in their daily routine.

- How each method would help them resist excessive screen time.

- Any anticipated frustrations or ways they might bypass the intervention.

From this test, we measured what people selected as interventions, we looked at engagement levels, user reasoning and preferences, reactions to intervention types, resistance to certain features, and adoption potential.

The results showed that users preferred customizable options over strict, forced limits. Gentle reminders and custom messages were well received, while more aggressive interventions were disliked. Social accountability features were effective but only when optional. These findings fit well with the Good Habit Jar because of the need for customization and user control. Instead of strictly limiting the users, the jar allows users to personalize their habit alternatives and offers gentle nudges rather than restricting them forcefully.

Key Takeaways

- Users prefer engaging and meaningful rewards.

- Negative reinforcement is surprisingly effective.

- Different work environments require different solutions.

- Customization is key. Users want to control how they manage their screen time rather than having strict, forced interventions.

Future solutions should balance motivation and deterrence while giving users more control over their own habits. A mix of gentle reminders, meaningful rewards, and optional restrictions may be the most effective way to help people reduce their social media use in the long run.

Intervention Study

Overall Learnings

The “Good Habit Jar” intervention had mixed effectiveness across participants, with most reporting minimal impact on their social media habits. Participants (N=4 ) were young adults aged 18-35 who self-reported peak social media usage times. We sent automated pings every two hours during these reported time windows over a 4 day period.

Each ping included:

- A changing collage of ‘good habit memories’ (e.g., past achievements, fun moments) meant to remind participants of positive offline activities. Each collage was personally tailored for each participant, and a new collage was introduced daily to keep the prompts fresh.

- A link to a Google Form with a few short questions:

- “Have you used social media in the last two hours?”

- “What social media did you use?”

- “How did your social media usage make you feel?”

- “Within the past two hours, have you engaged in any non-social media activity that made you feel happy, satisfied, or otherwise content?”

These questions aimed to capture not only the frequency and duration of social media usage, but also participants’ mindset around alternatives and the impact (if any) of the visual collage reminder.

What we Learned

- Intervention Effectiveness

- Most participants reported that the intervention had minimal impact on their social media usage

- One participant noted only reflecting on good habits when filling out the form itself

- The form-filling process often felt disconnected from the actual social media usage context

- Social Media Usage Patterns

- The average session length across participants ranged from 5 to 20 minutes.

- 67% of participants mentioned using social media primarily to fill downtime or procrastinate on tasks.

- Weekend usage patterns differed from weekday patterns (different apps, more intentional leisure use)

- Emotional Impact

- Mixed emotional responses to social media:

- Neutral or entertaining experiences were common

- Some participants experienced anxiety from social comparison

- Guilt was associated with distraction from tasks or in-person interactions

- Mixed emotional responses to social media:

- Alternative Activities

- Physical activities (gym, running, walking, dance) were reported as energizing and stress-relieving

- Social activities (eating with coworkers, visiting partners) provided positive alternatives

- Personal hobbies (gaming, baking, shopping) often competed successfully with social media use

- Individual Differences

- Existing goals (e.g., marathon training) significantly influenced whether participants chose alternatives over social media

- One participant’s decreased social media usage was attributed to a new gaming interest rather than the intervention

- Some participants viewed certain social media use (educational content, Strava) as positive or productive

Key Insights

- Self-Awareness Impact: Several participants reported becoming more aware of their habits through tracking alone, with one noting “I used social media less as I started tracking it,” suggesting observation itself can be a partial intervention.

- Self-Comparison Anxiety: The emotional impact of social comparison emerged as a distinct concern separate from general overuse, pointing to qualitative aspects of usage that may require targeted approaches.

- Activity Threshold: Activities requiring low activation energy (like watching videos) competed more effectively with social media compared to those requiring more setup or effort.

- Social vs. Solo Activities: Both social activities (eating with coworkers) and solo pursuits (running, gaming) proved effective alternatives, suggesting the need for varied options based on social availability.

- Existing Routines: Participants were more likely to engage in alternative activities that already fit into their established routines, like “sweet treat o’clock” for one participant or daily dog walking for another.

- Intrinsic Motivation: Personal interests and goals (marathon training, gaming) proved more powerful than the intervention itself, suggesting alignment with intrinsic motivation is crucial.

Intervention Design Limitations

- Cognitive Disconnection: The form-filling process created a separate cognitive task that took participants out of their natural behavior flow. One participant explicitly mentioned not noticing the positive affirmations in the text until late in the study.

- Reflection Timing: The reflection occurred after social media use rather than before or during, limiting its preventative potential. As one participant noted: “when I was reminiscing and when I was on social media were kinda two different moments and contexts.”

- Intervention Burden: The requirement to complete surveys may have created additional cognitive load that participants weren’t willing to incorporate into their routines. One participant suggested that “something that responds when I go to open it” would be more effective.

Re-Designing Our Solution

The core finding suggests that while reflection on positive habits has merit, the intervention needs to be more seamlessly integrated into users’ natural social media usage patterns to be effective.

Contextual Integration

- Create interventions that directly link to social media usage attempts rather than requiring separate form-filling

- Implement lightweight nudges that don’t take users out of their current context

- Consider a solution that responds when users actually open social media apps

Personalization

- Align interventions with users’ existing goals and interests

- Differentiate between types of social media usage (productive vs. unintentional)

- Account for varying usage patterns between weekdays and weekends

Reduced Friction

- Simplify the reflection process to minimize cognitive load

- As one participant suggested, create “occasional ‘hey look at the past'” reminders without extensive forms

- Focus on in-the-moment interventions rather than retrospective reporting

Emotional Framing

- Address specific negative emotions like guilt or anxiety from social comparison

- Highlight positive aspects of alternative activities rather than emphasizing guilt reduction

- Build on the positive experience of reminiscing that some participants reported

Environmental Triggers

- Design interventions for specific times when social media usage is highest (e.g., after work)

- Create specific alternatives for different contexts (work breaks vs. leisure time)

- Consider time-based interventions (e.g., before bed, as mentioned by one participant with a strict sleep schedule)

System Paths

To view the full system path diagram, please follow this FigJam link.

Listing our personas around the system path diagram, we first focused on what the ideal “happy path” through our solution would be. We focused on Eileen, our persona who would engage with our intervention to disrupt their frequent, unintentional social media use. This helped to form the core path through our system: the user encounters a popup that intervenes with their attempt at social media use, and if they are using it without intention, then they are presented with past habit memories and are offered some alternative activities to do.

As we added to our system path, we started to recognize the different use cases/entry points unique to each of our personas. These are represented in Rob and Gökçenaz, who have different interests in using the solution beyond the core path. Rob, who is interested in reminiscing on past memories, may want to view additional memories and add new ones. Gökçenaz, who is more disciplined about their social media use, might want to see memories/activity options to proactively counteract any tempting use.

Considering other important use cases, we focused our onboarding process for Mary, whom we saw as an interested new user. Importantly, this helped shape our process for inputting new habit memories, which we divided into manual inputs and pre-filled suggestions. This was important in our design as we wanted to lower user friction when it came to adding more entries. Our goal is to make it easy for early users to use the app, and build continual engagement over time.

From making our system diagram, we recognized four key use cases:

- The new user

- The existing/intervention engaged user

- The reflective user

- The proactive user

We combined the last two cases into our power user, thus resulting in three types of users. We also recognized where users would be inclined to exit out of our system (prematurely or otherwise), and made those cases explicit. These key findings ultimately shaped the three wireflows that we mapped and helped us focus on the key screens that needed to be designed.

Story Map + MVP Features

Our story map highlights the key aspects in our app that are necessary for the user to engage with our app in a meaningful way. To see the full story map (which includes a timeline and beta features), follow this FigJam link.

The first challenge is getting our user to commit to using our app, as we have a longer onboarding process that involves selecting/listing good habits and selecting which apps they want to track. Because of this, we designed our first MVP feature – onboarding – to encourage users to fill in the necessary information for using our app, and then confirming their account creation at the end.

Compare this to creating an account and then doing the onboarding process after logging in; the user could decide that doing that mental labor isn’t worth their time and every step is another opportunity for them to quit. We offer a login step after the onboarding process is already completed in order to:

- Encourage them to commit to account creation as they already filled out all the necessary information, and

- Make beginning app usage as seamless and effortless as possible, since there wouldn’t be additional labor to do after account creation.

The second key feature was actively logging and pursuing their good habits. We realized from story boarding that we wanted our app to be an encouraging and safe environment, not punitive, so we focused on integrating positive reinforcement tactics rather than guilt-tripping or constantly nagging our user.

What sets us apart from Apple’s regular Screen Time feature, for example, is that users can actively track and mindfully/intentionally pursue good habits rather than just being poked and prodded for too much screentime usage. The idea is that at the same time as reducing bad habits (in this case, overuse of social media), we foster and facilitate good habits as well.

Our third key feature was nudging the user when accessing a social media or otherwise restricted app past the predetermined allotted screen time. Story mapping helped us realize we didn’t want to turn into a punitive system, but nudging is still a critical part of the process in deterring users from acting on impulse or reflexive social media usage.

We imagined a screen time limit notification nudge and examined why it wouldn’t/hasn’t worked for our past study participants (namely, they could easily hit ignore and weren’t motivated to listen). We ultimately landed on providing a visual reward to help foster a sense of investment. This is how we created our ‘cookie jar visual’ idea, similar to how people who are becoming sober may keep a jar of marbles and add a marble each day. The idea is to provide a visual sense of their accomplishments–showing them that other alternatives are possible, that they’ve already done them and are capable, and encouraging them to keep going. By providing a visual reward, and reminding them of their predetermined alternate activities, we can doubly motivate them through a visual reward and redirecting their attention/need for mental stimulation towards a ‘healthy’ habit.

Our MVP features include:

1. Onboarding

Personalization is key. Users need to tailor their experience to stay engaged. Without this step, engagement would drop, and interventions wouldn’t be as effective.

- Select good habits to track

- Choose social media apps to monitor

- Set screen time limits

- Customize interventions (nudges, reminders)

- Confirm account creation

2. Tracking Good Habits

Users need reinforcement to reduce social media usage, not just restriction. Seeing their progress makes them more likely to stick with behavior changes.

- Log a new habit entry

- View habit jar progress

- Access past habit logs & reflections

- Receive habit suggestions

3. Social Media Nudges / Visual Element

Traditional screen time alerts are easy to ignore—interactive nudges and visual rewards make interventions more engaging and effective.

- Trigger pop-up when opening a tracked social media app

- Display a reminder of selected good habits

- Offer alternative activity suggestions

- Visual reinforcement (habit jar growth)

- Customizable nudge messaging

These three features are the foundation of the app. Without them, users wouldn’t be able to set their goals, track progress, or get the right nudges to stay on track. Onboarding ensures users personalize their experience, making them more likely to stay engaged. Tracking Good Habits gives them a way to see their progress, which keeps them motivated. Social Media Nudges help break mindless scrolling by reminding users of their goals at the right moments. For V2, we can add extra features like habit streaks, social sharing, or smarter habit suggestions, but these core MVP features are essential for making the app useful from day one.

Bubble Map

To view the bubble map in more detail, follow this link.

This bubble mapping process clarified the Good Habit Jar’s dual approach:

- Positive reinforcement through memories, streaks, and activities

- Intentional intervention via prompts, nudges, and app limits

The structure highlights how behavioral change requires both motivation and friction, ensuring users are supported while also being encouraging them to pause and reflect before engaging in impulsive behaviors.

A key insight from this process is that customization and balance are crucial. Users need flexibility in how they track progress and receive interventions to create meaningful behavior change.

While making the bubble map, we considered how users need options in how they track progress and receive interventions to ensure the approach aligns with their individual preferences. While some may respond better to gentle nudges, others might benefit more from stricter app limits. Given these diverse needs, our solution must provide adaptable tracking and intervention methods, allowing users to tailor their experience in a way that best supports their habit-building journey.