In recent years, depending on who you ask, AI has either infiltrated, revolutionized, or undermined higher education. For some students, it is the perfect study buddy; for others, it is a crutch. Regardless, it is clear that overreliance on AI means the death of critical thinking: already, research (and anecdotal evidence) has shown that relying on AI prevents students from learning. The first question that we might ask is: how might we harness AI’s immense potential as an educational tool while reducing its harmful effects – the risks? Of course, in the realm of this study, the harmful effects that we are discussing are relegated to its users. Any discussion of AI’s “risks” must overlook the irredeemably harmful effects embedded in AI’s chain of production, including but not limited to environmental destruction and exploitation of labor. We are not going to be addressing in this study how AI is the apotheosis of capitalist technologies, which, in their incessant hunger, seek to convert everything into capital. For now, as students in a computer science class, we can only ask: how might we reduce the harm that AI inflicts on its student users, while acknowledging the reality of its prevalence? Our goal is to help students create more healthy, sustainable relationships with their AI usage.

Literature review

We began with a literature review of AI’s use in education. Overall, we found that while AI can be a powerful education tool, it also has significant downsides. We reviewed a mix of experimental studies and longitudinal studies. The studies found that the more users relied on AI, the worse users’ cognition; while AI improves short-term performance, it impairs long-term performance, as users outsource their own thinking and critical thinking skills. This was true for students as well as engineers. Scaffolded, experimental studies found the most positive effects for AI use, when AI could be an “intelligent tutor” that could bridge learning gaps. With intelligent pedagogical incorporation, AI could possibly boost creativity and engagement. However, very few articles addressed the ethical ramifications of AI use, especially around data privacy, algorithm transparency, and trust.

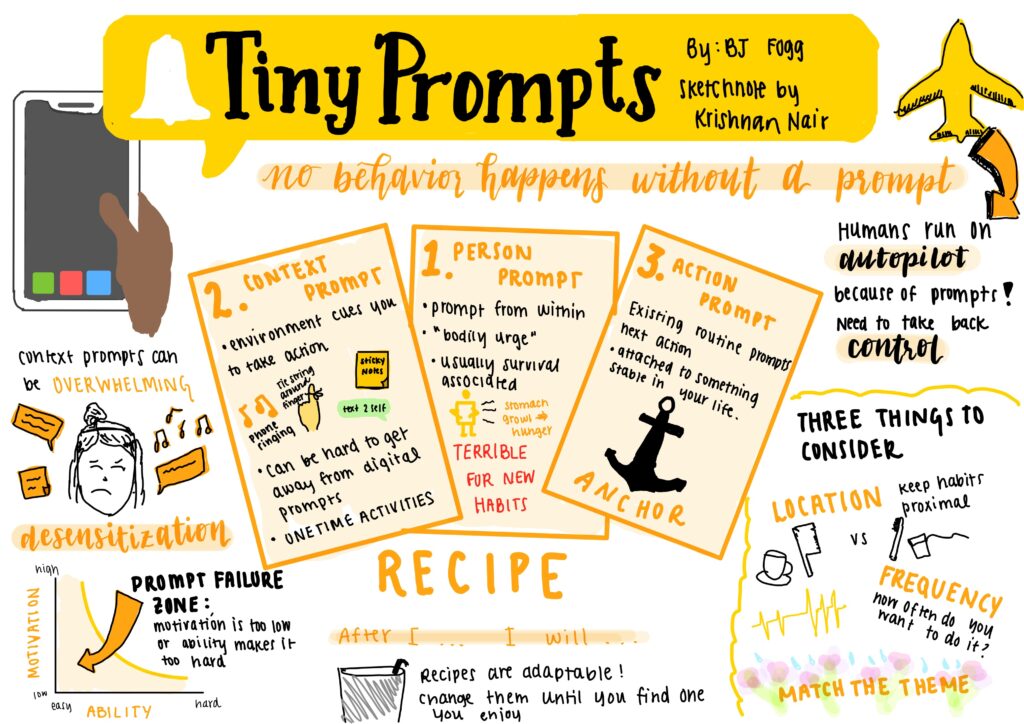

Comparative Analysis

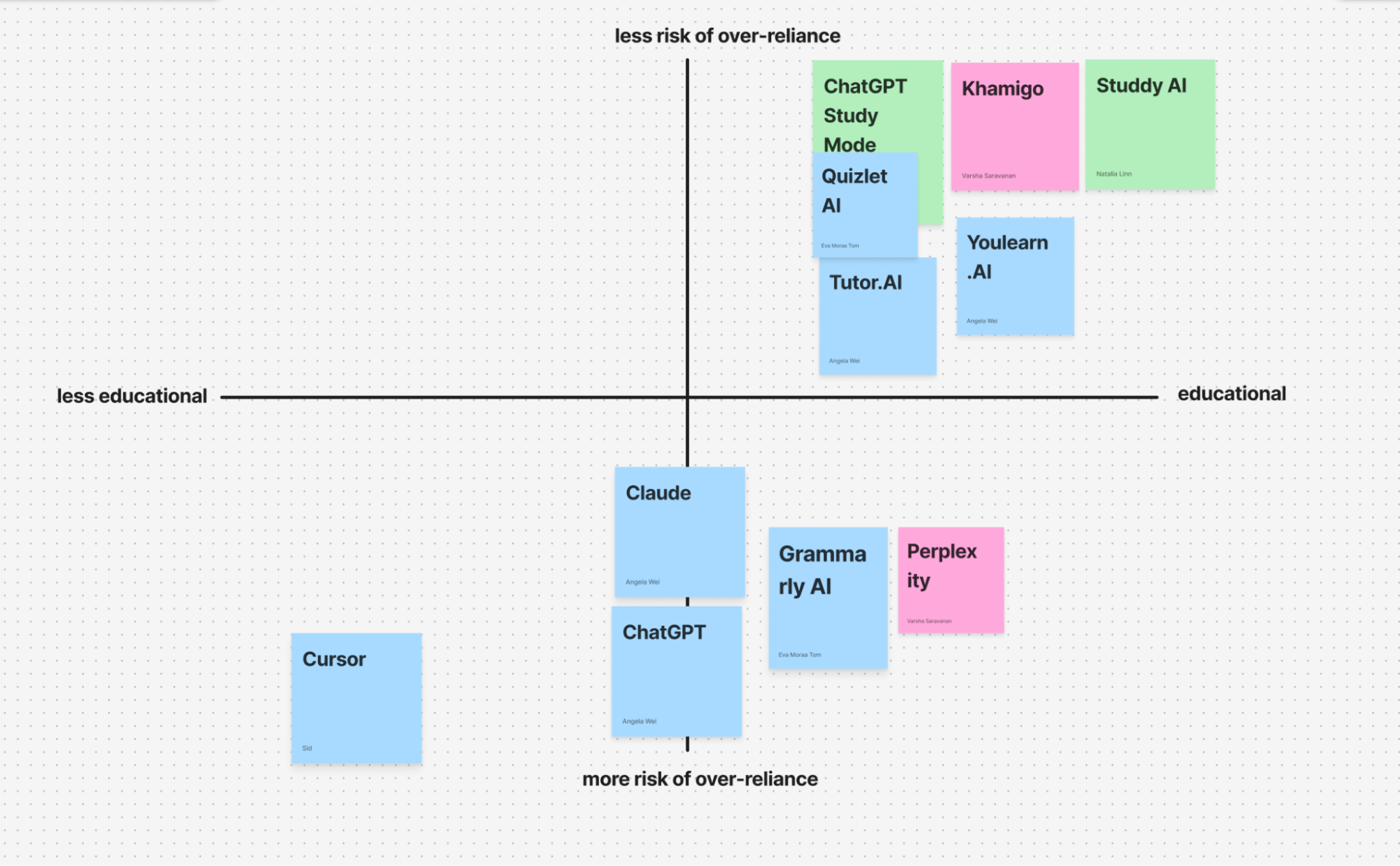

Next in our research process, we analyzed different tools currently available to mediate or enhance the AI learning experience. Across the tools we analyzed, we found a pattern when mapping products along two dimensions: educational scaffolding and risk of over-reliance. General-purpose AI assistants like Claude and default ChatGPT, while versatile and powerful, fell lower on the “educational” axis and higher on the “risk of over-reliance” axis because their value propositions emphasize speed and immediate answers. This makes them efficient but also rewards outsourcing cognitive effort. Similarly, Cursor, though highly integrated and powerful for developers, removes all friction through autocomplete and codebase indexing, increasing dependency while offering little scaffolding for conceptual understanding. On the other hand, tools specifically designed for tutoring, like Quizlet’s AI Tutor, Khanmigo, Studdy AI, and Youlearn, prioritize step-by-step guidance and structured learning experiences. These tools intentionally withhold entire answers. Instead, they scaffold understanding. They are placed higher on the educational axis and lower on the over-reliance risk. Still, even within the best educational tools, there is still the problem that many still provide the option to provide the full solutions immediately, which defeats the purpose of their design, given that students are in the market for a quick answer.

Synthesized Research

We chose the two axes of our comparative graph (educational scaffolding and risk of over-reliance) because they emerged from the literature review and the patterns emerged from our comparative analysis. Across studies, researchers consistently found that AI improves short-term task performance while impairing long-term cognition when it replaces hard work and effortful thinking. Overreliance is not just about how often AI is used, but about outsourcing the cognitive effort of problem solving entirely to AI. When students do this, their retention, application, and critical thinking worsen. Scaffolded AI tools, where the design gave AI the role of “tutor” through guiding questions, produced more helpful outcomes. These findings aligned with the distinction we found in our comparative analysis. Tools higher on the educational axis (ie. Quizlet AI Tutor, Khanmigo, Studdy AI, ChatGPT Study Mode) are designed to scaffold learning through step-by-step prompting and Socratic questioning. In contrast, general purpose assistants (Claude, default ChatGPT) emphasize immediacy, aligning with the literature’s warning about long-term cognitive erosion when used as a shortcut.

Our graph therefore visualizes an insight: we can mitigate the risk of over-reliance by designing our agents differently. Our lit review highlighted the fact that pedagogical design is key to positive results. Our comparative analysis shows that some tools try this incorporation via built-in friction (refusing immediate answers, offering guidance, checking understanding) while others optimize for speed and complete results with minimal resistance. Even the tools in the “educational and less over-reliance” quadrant often still have optional shortcuts: the line between tutor and answer-engine is thin.

Figure 1. Graph displaying our comparative analysis on two axes, educational and risk of over-reliance.

Baseline Study

Target participants

Our target participants for our baseline study consisted of students (undergraduate and graduate) who use AI tools, like ChatGPT, Claude, Cursor, etc. We attempted to get participants across various disciplines, year levels, and institutions to capture the prominence of and reliance on AI tools.

The reason why we chose to focus on this group specifically was because AI usage is especially prevalent among students. However, the patterns of usage and motivations behind relying on AI are still relatively unexplored. Students are navigating a landscape where AI can serve as a tutor, a coding partner, a ghostwriter, or an entire cheating tool. The boundaries between what would be considered a productive use of AI versus complete over-reliance is blurry. If we can help students, we can also gain a broader understanding of how we can use AI more effectively and responsibly.

To identify our target participants, we sent a screener survey that asked about educational status, field of study, frequency of AI use, specific AI tools used, etc. The screener was primarily sent through our personal networks, which resulted in 14 respondents. From these, we selected 12 participants who represented a range of AI usage frequencies and academic disciplines (computer science, engineering, design, biochemistry, sustainable design, symbolic systems, and natural sciences) so that we can collect truly diverse data.

Our participant pool included students from Stanford, UCSB, UCLA, and a university in Kenya, ranging from freshmen to graduate students. More notably, their AI usage patterns varied from near-zero (using AI only a few times a year out of curiosity) to extreme power users (cannot survive without AI). Several participants were also balancing academic work with startup development, TA responsibilities, or other creative outlets, which added valuable context for when and why students depend on AI.

Key research questions

To guide our baseline diary study, we defined a set of research questions centered around student motivation, usage patterns, and outcomes related to AI-enhanced or AI-guided academic work. Rather than only measuring frequency of use, we wanted to understand the context, intention, and perceived impact of AI use in our target audience of college students. These questions informed our diary study as well as our pre- and post-interviews.

- What situations and pressures lead students to choose AI for academic work?

We studied common triggers such as time pressure, task difficulty, cognitive overload, uncertainty and convenience, and how these factors influence participants’ decision to turn to AI instead of other resources.

- How are students using AI across different academic tasks?

We studied which types of tasks students typically go to for AI support, ranging from concept understanding, coding, writing, editing, and planning, and we specifically pay attention to what stage in their workflow AI is introduced.

- How does AI use affect students; perceived learning, confidence, and emotional response?

We tracked how students feel after using AI and their self-evaluation of their understanding, looking at signals such as confidence, productivity, guilt, or concern about overreliance.

- How intentional is student AI use, and do students achieve their original goals when using it?

As an intervention, we plan to gauge student reported intentions with end of day reflections to identify whether AI use is deliberate and thoughtful, and whether outcomes align with students’ stated goals.

Methodology and data collection

We had twelve participants take part in our eight-day baseline study that ran from 1/20/2026 to 1/28/2026. They participated in a baseline interview, a diary study, and a post-study interview. To maintain a diary, our participants logged in their AI usage habits on a Google Form (template) on a daily basis, and we tracked their responses on a Google Sheet. They received reminders to fill in the form at the end of each day around 9pm via text message as shown below:

Figure 2. Sample text message that reminded participants to submit their entries.

The diary had thirteen questions, asking the participants about their AI usage that day. The questions included: how many AI sessions they had had that day, what AI models they had interacted with, and how long they had used the AI model for. We gave each participant a participant ID – a combination of their moderator’s name and a number – which they used for each daily entry. This allowed each participant to be more honest in their answers.

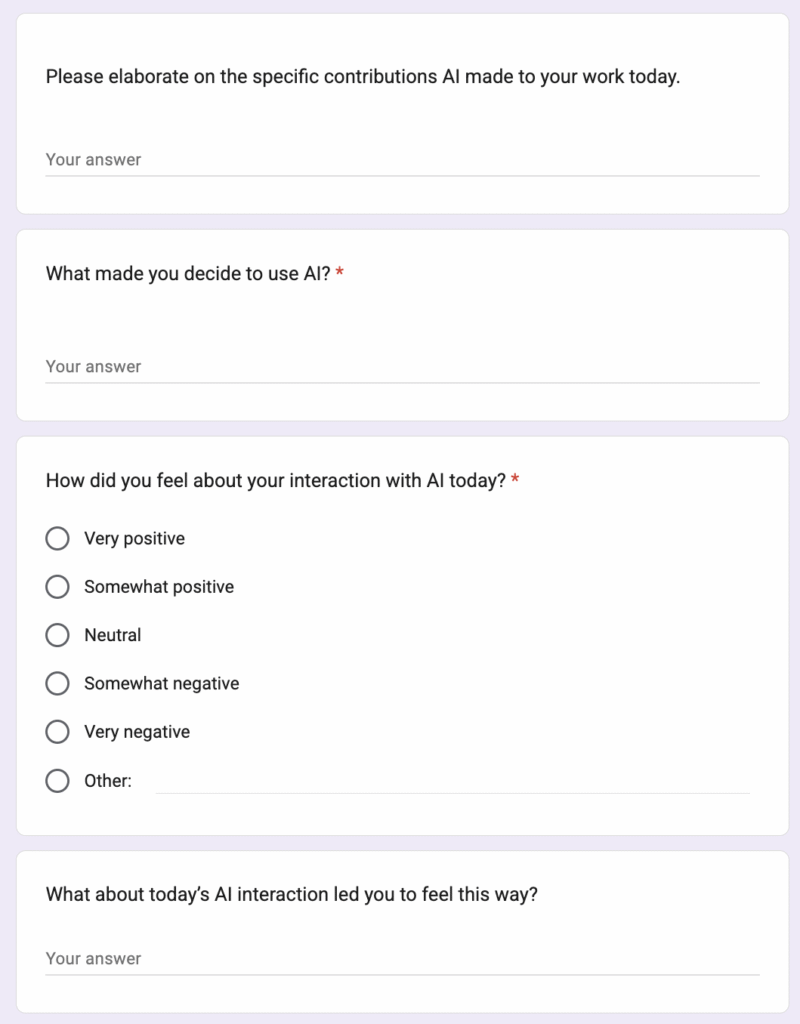

Our diary had a mix of open-ended questions and multiple choice questions. This is because we wanted to ensure that the form felt easy to fill out, while allowing participants some more flexibility and freedom for qualitative insights. For example, how long they used AI for was a multiple-choice question, while follow-up questions about participants’ feelings were open-ended. For some, we used multi-select multiple choice answers so that participants would not feel restricted to one answer only: for example, “For what academic tasks did you use AI today? (Select all that apply)”.

The most important question on our questionnaire was evaluating their feelings about their interaction with AI. Initially, we were thinking about using multi-select with options like “happy,” “neutral,” or “sad”; however, this felt too leading. Meanwhile, the open-ended question felt like it was too vague: what does it mean to “feel” a certain way about AI? Therefore, we chose to use a scale that ranked their interactions from ‘very positive’ to ‘very negative’ to ‘other.’ This allowed users to freely choose, without suggesting a particular answer.

Figure 3. Screenshot of a part of the daily questionnaire.

The responses can be found here in this Google Sheet: Diary Study: AI Usage for Students

Synthesis

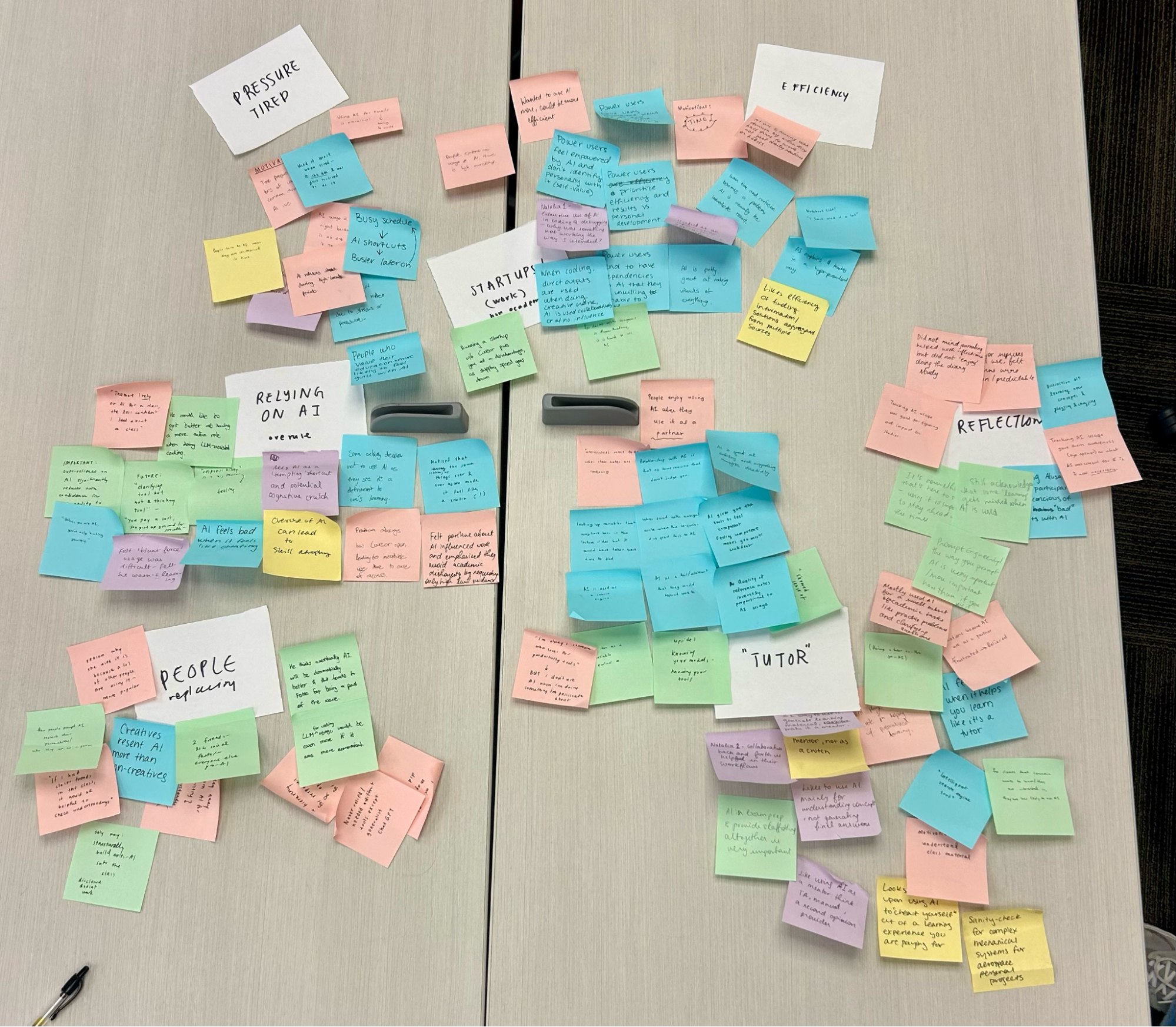

To synthesize the baseline interviews, diary entries, and post study interviews, each team member created sticky notes capturing key quotes, observations, insights, and emotional signals from the participants they personally studied. We intentionally mapped participants we interviewed ourselves so we could incorporate non-verbal signals such as hesitation, confidence, stress, and guilt when interpreting their responses, rather than relying only on written answers.

Upon synthesis, we noticed a large number of notes and conducted an affinity mapping exercise to cluster related observations. We grouped notes based on shared patterns in motivation, intentions behind AI use, decision triggers, emotional responses and AI use behaviors. Our clusters focus especially on moments where students’ described intentions did not match their actual behavior, as well as repeated triggers that led them to rely on AI.

Our affinity groups are:

- Time Pressure and Low Energy

- Efficiency

- Startup Pace and Workload Strain

- AI Overreliance

- Need for AI as a Guided Tutor

- Self Reflection

- AI Replacing Human Effort

Figure 4. Sticky-notes from our affinity mapping process.

From the affinity clusters, we observed that AI use is most often triggered by pressure, time constraints, and lack of mental energy rather than laziness or lack of effort alone. Students repeatedly described turning to AI when deadlines were stacked, when they felt “burnt out,” or when they were switching between school and other commitments such as startup work, TA duties, or side projects. AI was framed less as a novelty tool and more as a pressure response or stress mitigation tool. A strong pattern that emerged was a split mental model of AI as both a tutor and a shortcut. Many participants described AI as a learning support system that helps explain concepts and unblock confusion, yet in practice they often ended up using the tool as a shortcut when efficiency became the priority. This created a recurring tension between scaffolding forward use and efficiency maximizing use, indicating a key discrepancy between intended use and actual use.

Looking closer at this discrepancy between intended use and actual use, several students described personal rules for themselves, such as using AI only for clarification or only after attempting problems independently, but diary logs and interviews showed that these rules were often bypassed under stress. Many participants were aware of this mismatch and reported guilt, discomfort, or concern about overreliance after the fact. Trust and convenience appeared closely linked across clusters, with students describing AI as always available, non judgmental, and faster than office hours or peer help. This low friction access often made AI the default first step rather than a supplemental resource.

At the same time, reflection related clusters showed that when students paused to evaluate the nature of their AI use and whether it actually supported their learning, their behavior became more intentional and selective. This insight directly informed our intervention direction around intention setting, reflection, and providing usage indications as a means to promote self awareness in students.

Grounded Theory

We developed several grounded theories that dive into the behavioural patterns of students that use AI for their school work. These theories are relevant to our top four interventions: Brain Rot indicator, Tutor your prompts, custom GPT scaffolding, and a self reflection quiz, which are all illustrated in our storyboards.

The core of our grounded theory is that students rely on AI for two main reasons: competitive necessity and crisis management. We observed that students with outside commitments, for example startup founders who were still in school, relied heavily on AI assisted coding to maintain competitive development speeds while also balancing their school loads. This behavior is not about cutting corners, but it shows the impossibility of pursuing two things at once without AI assistance.

Moreover, we saw that AI serves as a ‘quick fix’ for students experiencing cognitive overload. Because of back-to-back academic demands, the ease and non-judgemental nature of AI makes it the default option. In both situations, there is confidence when using AI which quickly turns to guilt when the student becomes overdependent on it, and the students consciously avoid using AI in courses they care about. This everyday use that leads to over-reliance is the reason we chose the brain rot indicator as one of the interventions, because we want students to be aware of how much AI usage everyday is contributing to their mental state. The brain rot indicator, coupled with our self reflection quiz at the beginning and the end of the day, will create awareness on how much AI is being used, and whether their intentions were achieved or not while using it.

Our grounded theory document provides a well detailed analysis of subtheories that explore the relationship between the students, AI models, their coursework, and course policies, as well as their motivations and the situations that influence their decision making process with regards to using AI. It is through this framework that we came up with our interventions, with the hope of making students use AI more responsibly, so that they achieve their academic intentions and meet their goals.

System models

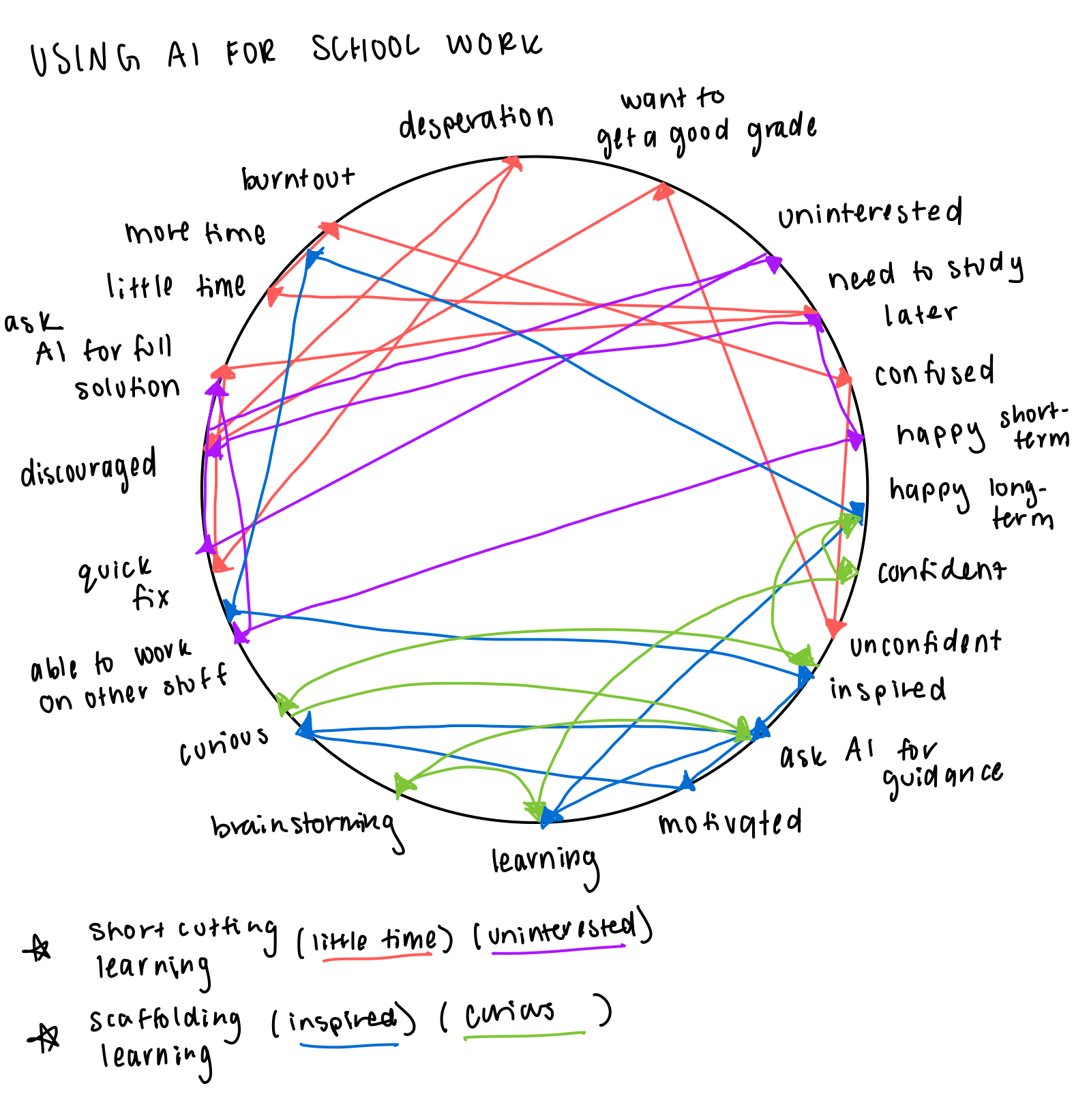

FEEDBACK LOOP

Figure 5. Feedback loop model

The feedback loop model shows how the motivation behind AI usage can lead to actions that reinforce the habit in a loop. There are two groups of loops: shortcutting learning and scaffolding learning. These groups are to distinguish the healthy AI usage loops from the unhealthy AI usage loops. A student using AI in a way that shortcuts their learning is seen as unhealthy behavior as it can yield short-term benefits but burden the user in the long-term. A student using AI in a way that scaffolds their learning is seen as healthy behavior as it can yield long-term benefits despite the short-term time sacrifice and friction of learning.

Within shortcutting learning, there are two loops: “little time” and “uninterested.” “Little time” represents the student that perceives the value of efficient completion of an assignment as higher than the value of learning it deeply in that moment. In this loop, the student is busy and burnt out which leads them to struggle to finish the assignment, they lose confidence in their ability to do it on their own and get a good grade so they ask AI for the complete answer and copy it. This results in them needing to study those concepts later which steals away time from their future self, who is even more pressed for time and resorts to AI again. “Uninterested” represents the user that doesn’t want to learn the content of the assignment, so they use AI to solve their problems so they can work on something they are more inclined to do. They find themselves in a loop where they start apathetic, learn nothing from copying off of AI, become even less interested and more discouraged, they need to study more in the future with no motivation, so they rely on AI even more and become increasingly uninterested. As for the scaffolding learning group, we have “inspired” and “curious.” “Inspired” is a student who loves the content of their assignment and really wants to internalize it. Their inspiration motivates them to be curious and ask AI for guiding questions to their problems, this causes them to learn, making them happier long-term and affording their future self more time to work on other passions which in turn inspired them to learn. “Curious” is a student who uses AI to explore their ideas, when they brainstorm with AI through guiding questions, they learn and become more confident in their imagination and projects, this supports their project building and inspires them to be curious more often. This model shows how different behaviors with AI can enforce different learning instincts and results in students long-term given how the habit proves itself.

STOCK AND FLOW MODEL

Figure 6. Stock and flow model

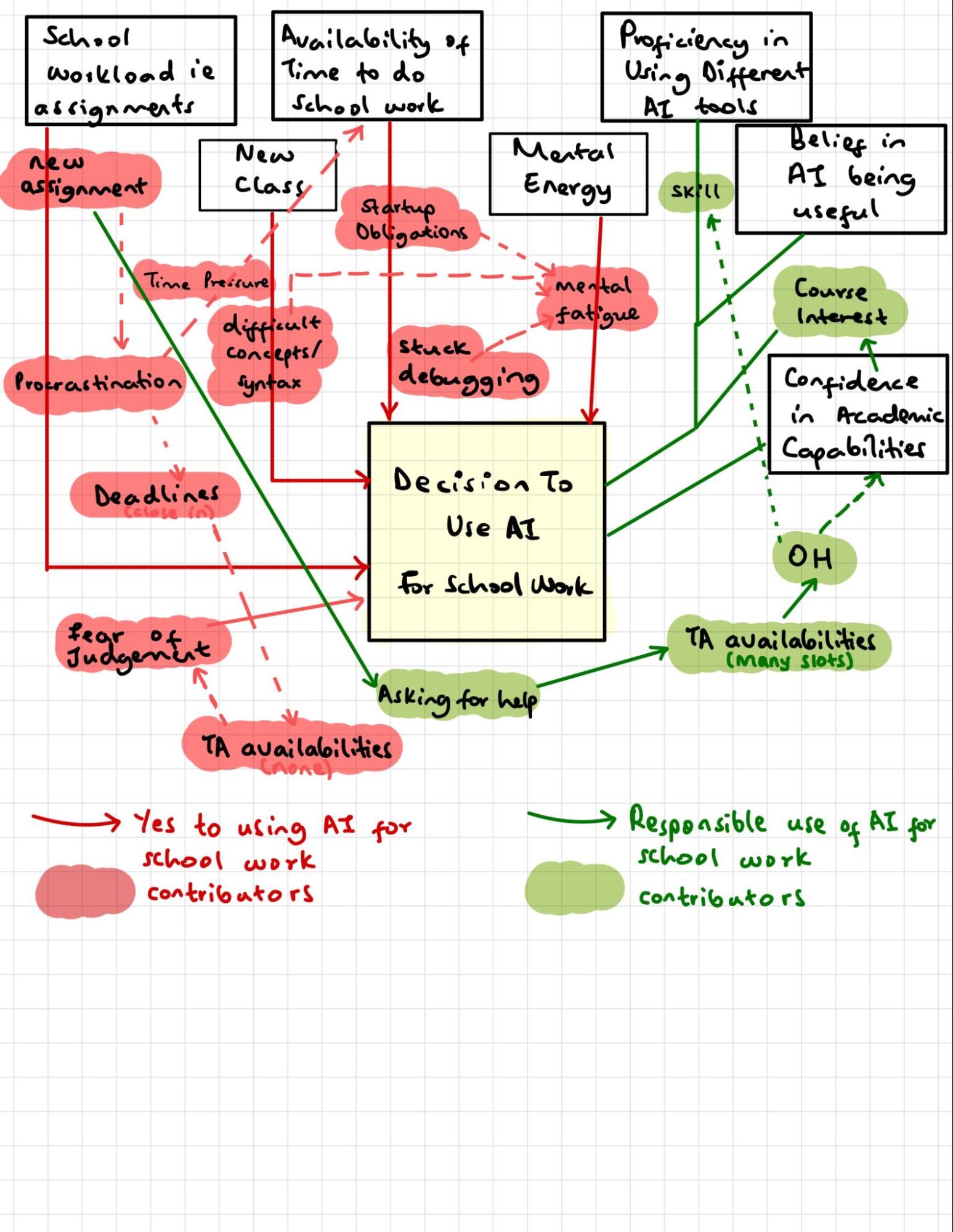

This system model shows the decision-making process of students when they want to use AI for school work. The model has seven stocks: School workload, Availability of time to do school work, Taking a new class, Mental energy, Proficiency in using AI tools, Belief in AI being useful, and the student’s confidence in their capabilities. From the model, we see that students decide to use AI when the pressure from accumulated workload, time pressure, difficulties in taking new classes, deadlines, and mental fatigue exceeds a threshold. We also see that when the perceived value of AI is coupled with the student’s interest in the course material, this boosts their academic confidence and motivates them to study independently of AI.

The model shows two loops: the competency decline loop and the efficiency reinforcement loop. In the former, AI usage leads to reduced school work practice, which leads to decreased mastery of the subjects and coursework, and consequently fuels the student’s dependency on AI. The latter loop shows how successful AI usage looks like, where knowledge on how to use AI responsibly leads to students using AI moderately while still primarily relying on their TAs and course staff for academic help, since they are fuelled by course interest and want to deepen their learning.

This model shows the paradox of students wanting to use AI to save time, but instead of the AI helping them understand and learn, it perpetuates the cycle of overworking, which ultimately traps the students in a cycle of continuous reliance without any time saved.

FISHBONE MODEL

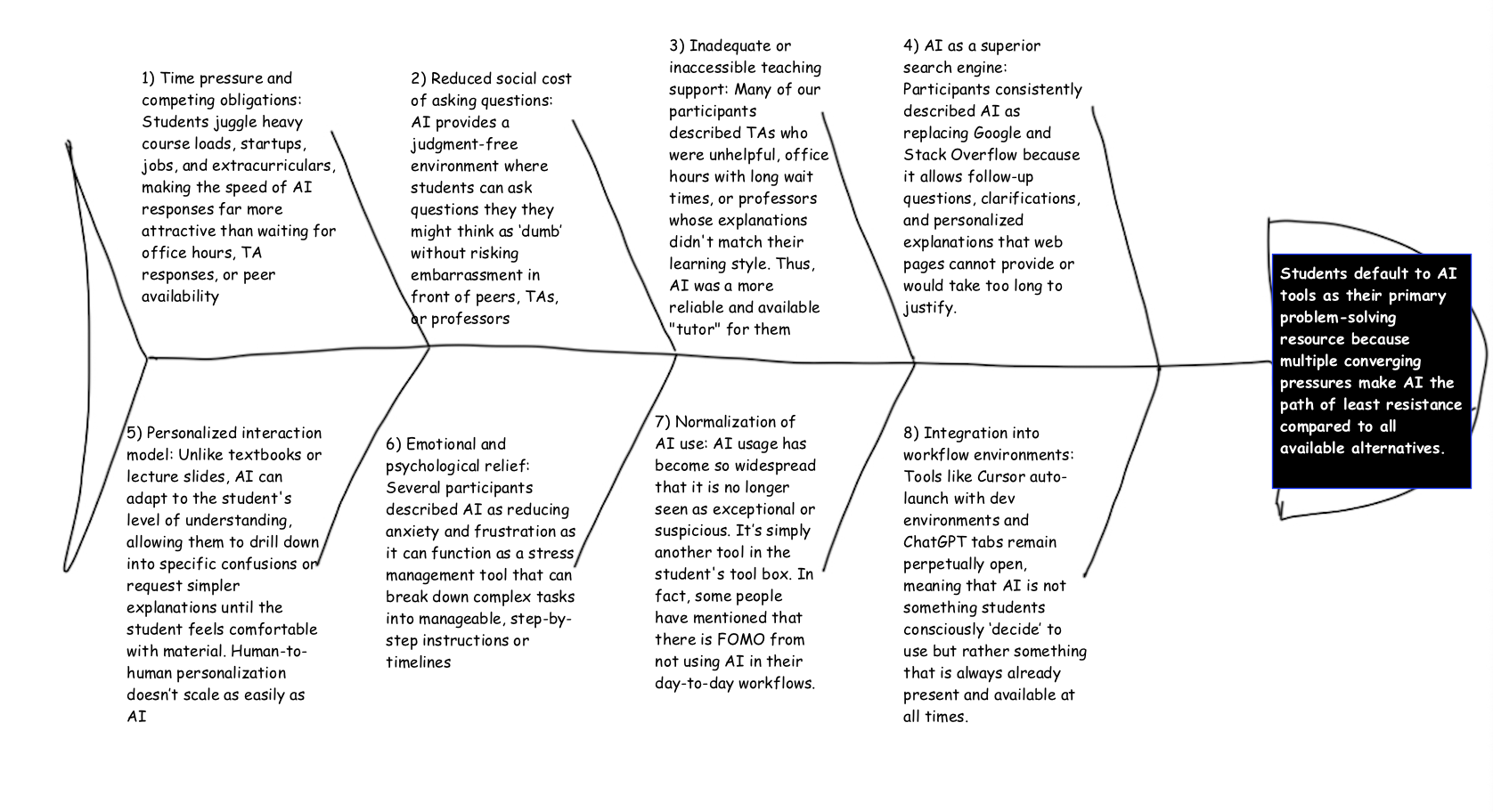

Figure 7. Fishbone model

This fishbone model shows the high-level forces that lead students (over)rely on AI as the default resource rather than as a supplement. Our interviews and diary data repeatedly surfaced a pattern: students did not start using AI on the presumption that they’d rely on it heavily, but rather a mix of different pressures, like time scarcity, social anxiety around asking questions, inconsistent quality of human support, and the sheer convenience of an always-on helper. One participant described his startup work as “near-impossible without Cursor,” while another noted that before AI, solving bugs “could take days” and involve office hours and tutoring sessions. The friction of accessing human help versus the completely frictionless process of accessing AI help creates a powerful attraction.

Our fishbone model reveals the problem of AI reliance is not due to individual willpower or laziness, which is a misconception that several participants explicitly pushed back against. One participant emphasized that “students are not lazy, they are stressed about a lot of things,” while another participant pointed out that “if you’re not using it, there are some ways that you’re at a disadvantage.” This tells us that an effective intervention must address the system that makes AI the default, not simply try to restrict access or shame usage. In our early discussions, we quickly realized that focusing on the latter would result in ineffective solutions; therefore, understanding the pressures identified in the model helps us identify where introducing friction or reflection could redirect behavior without creating resentment or impracticality.

ICEBERG MODEL

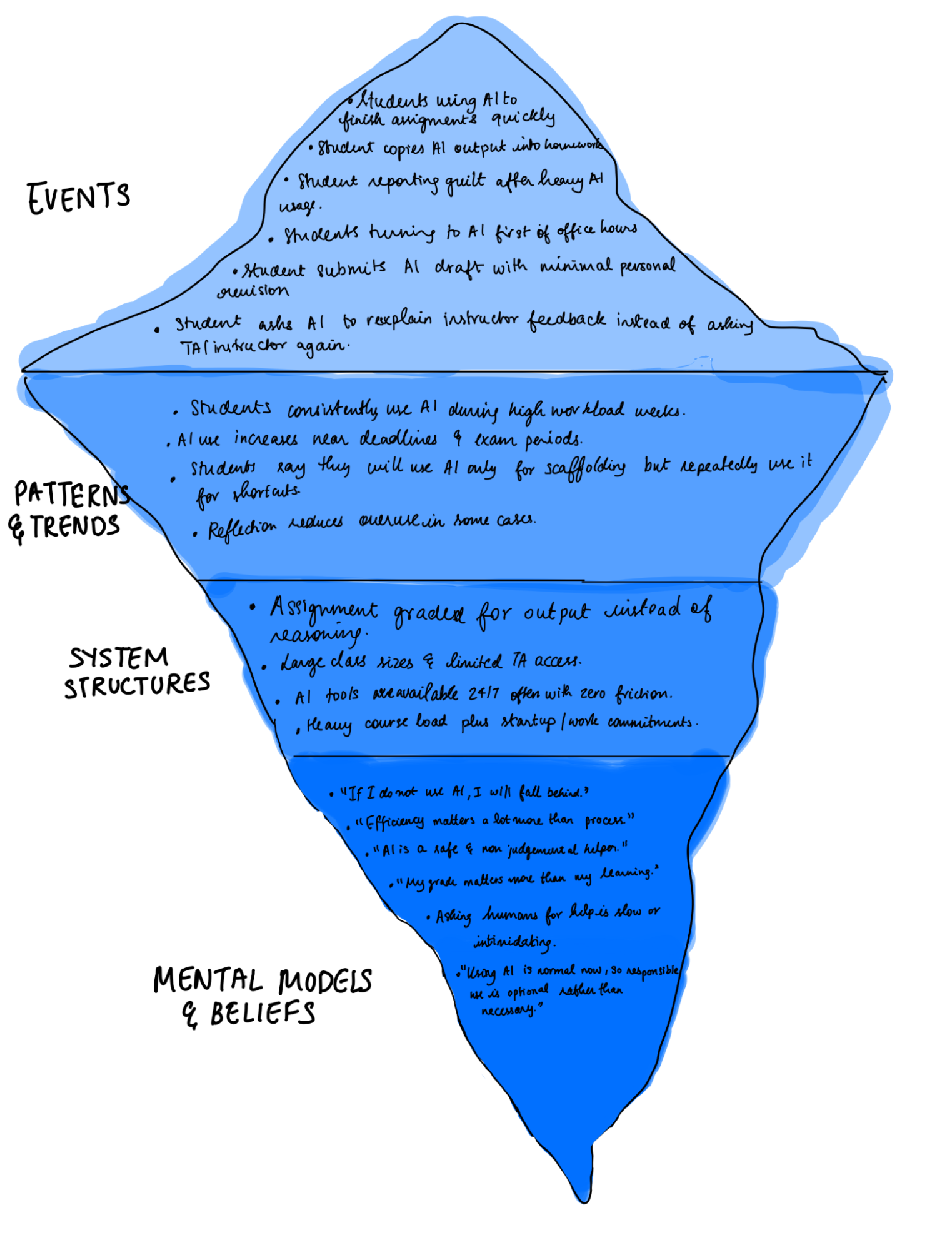

Figure 8. Iceberg model

The iceberg model shows student AI use in academic work across multiple depth levels, moving from visible behaviors or ‘events’ to underlying mental models and beliefs. Rather than focusing only on observable AI use events, the models help explain recurring patterns and trends, system structures, and mental models that drive student reliance on AI tools.

At the surface level, the model captures observable events such as students using AI to finish assignments, copying AI generated output into homework, submitting AI assisted drafts with minimal revision, and turning to AI before office hours. WHile these are the most visible signals of AI reliance, they do not fully explain why the behavior appears so consistently across students and contexts. Looking a layer deeper, patterns indicating repeated behaviors over time emerge. Students use AI more during high workload weeks and near deadlines, often introduce AI earlier in the workflow, and often say they use AI for scaffolding but end up using it for shortcuts. Moments of reflection sometimes reduces overuse, suggesting that awareness can interrupt default reliance and that AI use is often a result of repeated high pressure situations rather than one off choices.

At deeper levels, the model highlights the system structures and mental models that propagate these patterns. Structural factors include assignments graded mainly for output instead of reasoning, large class sizes with limited TA access, restriction-free AI tool availability, and heavy course loads combined with outside commitments. These conditions make AI the lowest cost help channel compared to human support. At the deepest level, student beliefs further reinforce the behavior, including fears of falling behind without AI, prioritizing efficiency over process, viewing AI as a safe alternative to human help. There is also a growing sense that since AI use is normalized, responsible use is optional rather than necessary. Taken together, the iceberg model shows that AI overreliance is not just an individual behavior issue but a system level effect shaped by pressure patterns and beliefs that are shaped over time.

SYSTEM INPUT/OUTPUT MODEL

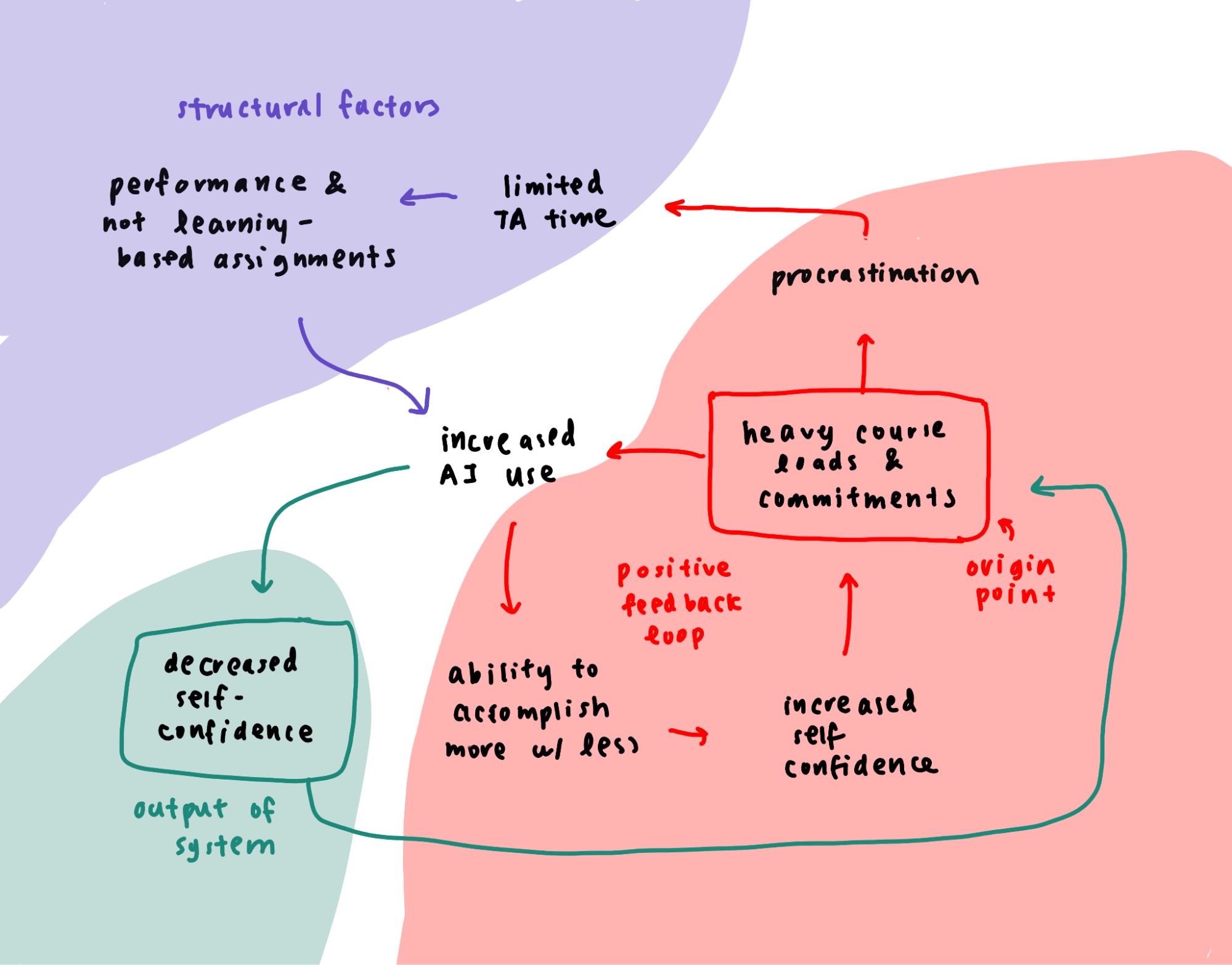

Figure 9. System input/output model

This system input/output model focuses on the interaction between structural factors and individual factors for increased reliance on AI. The model highlights one important feedback loop, which originates from heavy course loads and commitments. This leads to increased AI use, which leads to accomplishing more with less, which means that the person is self-confident enough to continually tackle more course loads and commitments. When this interacts with procrastination, however, the structural factors become more evident. As TAs have limited time and assignments are graded on performance, students are encouraged to use AI more frequently – there is just less friction. Overall, the system outputs an overall decrease in self-confidence in the students’ ability to do work.

This points out a significant contradiction: how can the student have increased self confidence and decreased self-confidence? What the model implies, however, is that this increase in self-confidence is short-lived. In the short term, students might feel like they are accomplishing more with less, and feel confident that they are excelling in their classes, exacerbated by assignments that allow AI use – most likely because they are problem set based classes. In the long-term, however, students feel a decrease in self confidence because they are relying on AI too much – which then pushes students to tackle heavier course loads to increase their self-confidence once again.

This brings us to our conclusion, which is that in order to intervene at any point in the system, it is important to rethink the performance-based assignments (which push students to produce better, faster, more efficiently, without learning). It is even more important to target students’ heavier course loads and commitments, which is the input to the model, from which everything originates.

User personas and journey maps

To improve our understanding of our users, we then made user personas and journey maps.

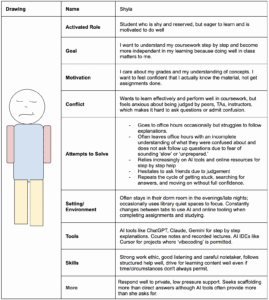

PERSONA 1: Shyla, the Shy Student

Figure 10. Behavioral persona “Shyla”

The above behavioral persona ‘Shyla’ represents a shy but highly motivated student who cares a lot about her academic performance. She wants to understand concepts in a step by step manner and build independence in problem solving, not just complete assignments for the sake of submission. However, fear of judgement from peers, TAs, and instructors makes it difficult for her to ask clarifying questions or admit confusion. As a result, she finds herself turning to AI tools and online resources that are low pressure channels to get help before reaching out to people. She has a strong work ethic and follows structured guidance well, but often leaves office hours without full clarity, often from fear of asking too many clarification questions. She benefits most from having private, supportive scaffolding help that reduces social pressure while still guiding her to develop an understanding of concepts.

Figure 11. Shyla’s emotional journey

Shyla’s emotional journey begins with focused determination mixed with pressure as she starts her work and tries to solve problems by herself. However, when she gets stuck, her confidence drops quickly and she is quickly flooded by frustration and self doubt. Given her shy nature, she hesitates to ask questions publicly and instead turns to AI to give her step by step help. This gives her relief and a sense of safety because she can ask freely without being judged. However, this relief is rather temporary, since the support sometimes gives her answers faster than she can fully process them. By the time she submits her work, her emotions dip again into uncertainty and mild guilt because she knows her understanding is incomplete and is left feeling like an imposter. The journey ends with worry about future exams and concepts even though the immediate task is finished.

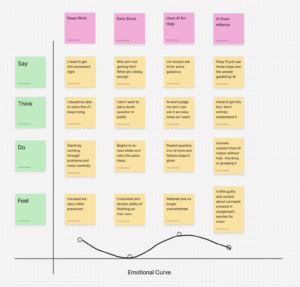

PERSONA 2: Greg, the Tired Student

This is Greg – the tired student. Greg is the most typical Stanford student you’d see around — we’re all Greg, in our hearts — but Greg has it real bad. Unfortunately for Greg, he is at his core a very high achieving, successful CS student, but life circumstances has got him down! He needs AI because he has yet again planned his quarter for his best version of himself: going to the gym every day, sleeping early, finishing work early. 22 units? I got into Stanford — I can do it! But he can barely make it through each day without falling asleep. AI makes sure that even though he’s so tired, he can still succeed. But because AI exists, he’s even more inclined to procrastinate, believing that he can get every Pset done in “just a couple hours.” This isn’t the college experience he was promised. But maybe, at the end of the day, that’s what Greg wanted a little bit: he wanted to prove to himself that he can do it. He still can. He still can.

| Drawing | Name | Greg |

|

Activated Role | Tired student |

| Goal | I want to GET MY STUFF DONE! (at all costs) | |

| Motivation | Because I want to just go to sleep… I’m so tired all the time. | |

| Conflict | I have way too much work to get done in a reasonable amount of time… I’ve enrolled in 22 units again, thinking that, maybe, this time it would be different… I take too much on, and this is the price I have to pay | |

| Attempts to Solve | I’ve tried using AI — of course — I’ve tried too many paid productivity tools, like planners (which never end up working), I’ve tried staying up more to finish things, but it never ends up panning out, and just makes things work. | |

| Setting/ Environment | My dreary, sad, bare dorm room. I don’t decorate — who do you think I am? You think I have time for that?

Also, occasionally, CODA. |

|

| Tools | ChatGPT is my best friend. Back in the day I used Chegg… I tried using blockers (for Instagram, etc.) but I just end up uninstalling them. My Google calendar is a nightmare. | |

| Skills | I’m good at the last-minute P-Set: it’s my specialty. I know everything about the various AI tools and what they’re good for. | |

| More | This is how it goes: I sleep late, which means I wake up late. I’m groggy — chug coffee (doesn’t work) — and then I get to working. I work all day, but because I’m so sleepy and exhausted, I can’t finish my work early; I get so distracted by things like Reddit or Instagram. This means I stay up late for that 11:59 pm deadline — which cascades the problem. |

Figure 12. Greg’s behavioral persona.

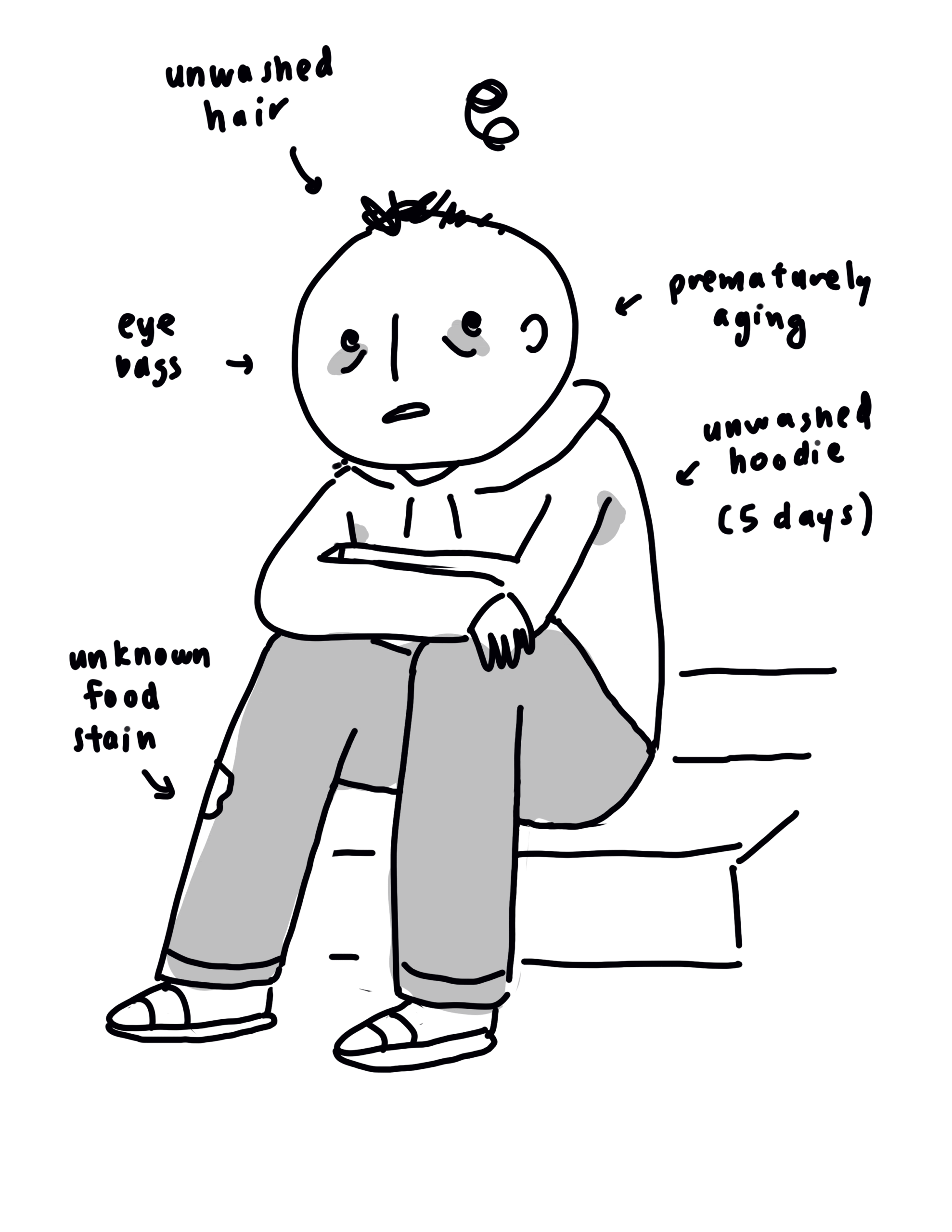

This journey map documents a study session: an optimistically too-late study session.

Figure 13. Greg’s journey map.

Here’s a link to the FigJam.

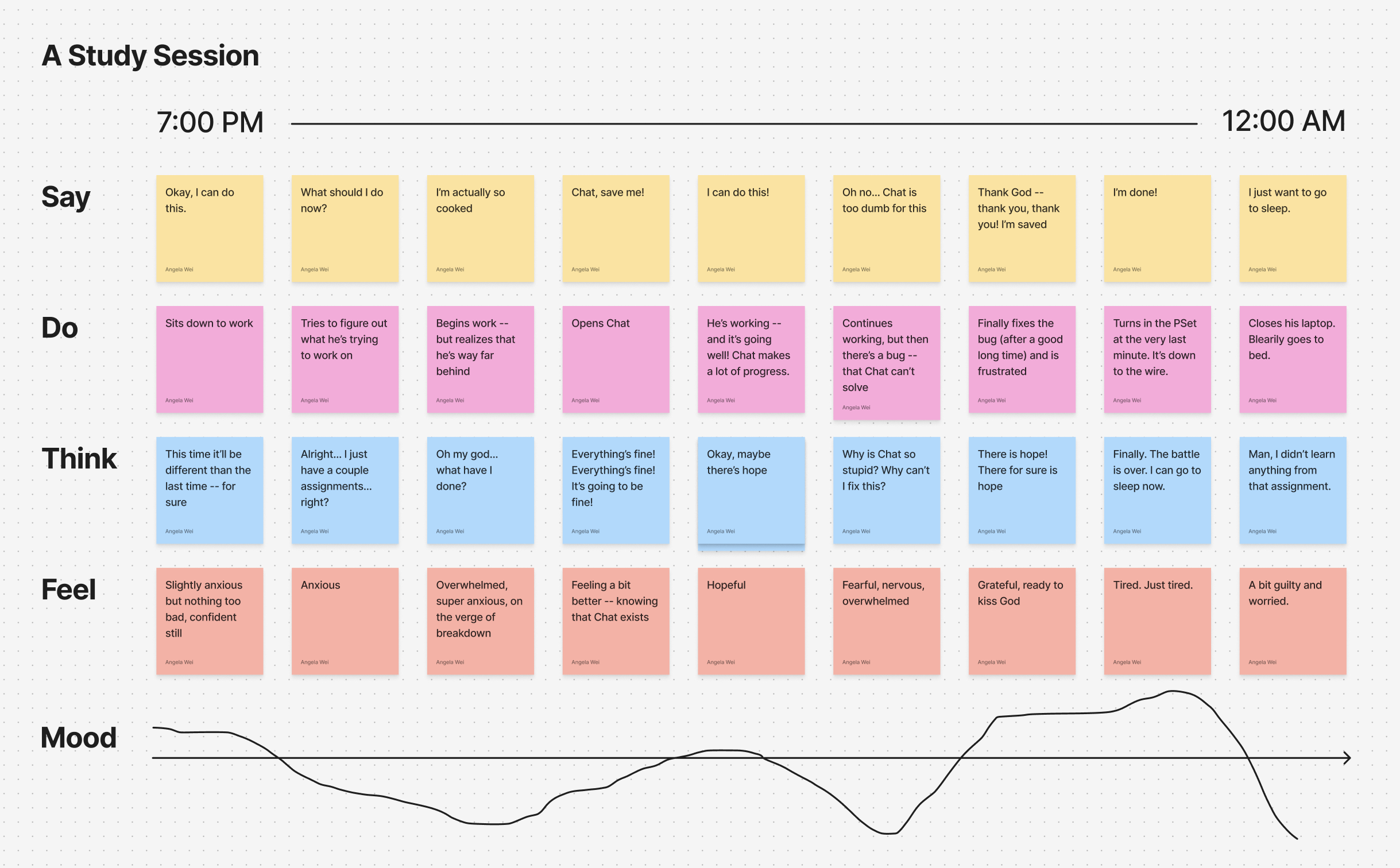

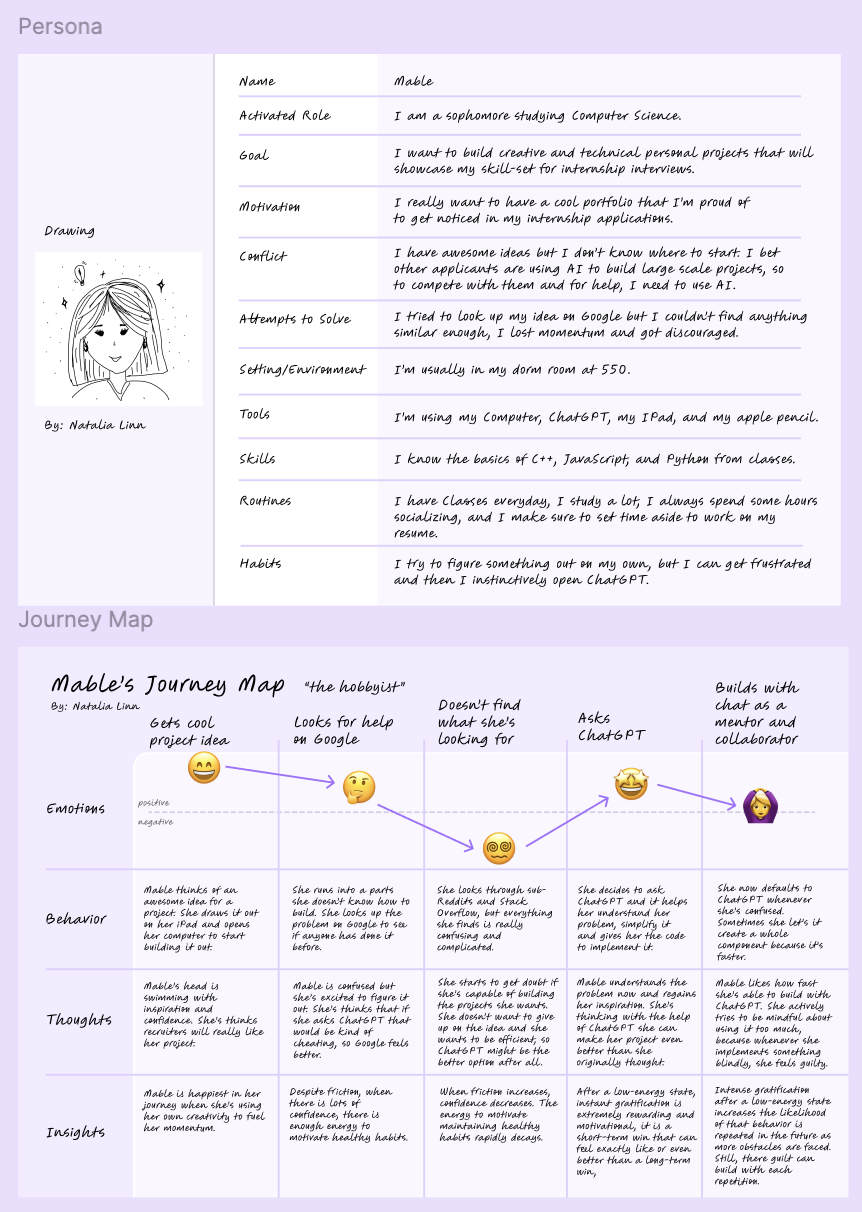

PERSONA 3: Mable, the Creative Student

Mable represents the type of student who uses AI to help build personal projects. She’s motivated by wanting to build out her big ideas and put them on her resume for job recruitment, but she doesn’t always know where to start. She likes using AI as a mentor to help her through roadblocks. It’s helpful to her when it creates step-by-step instructions on how to build a certain part. However, whenever she uses AI directly in her project, she feels guilty, especially if she doesn’t understand the implementation and she just decides to move on in the interest of time.

The journey map below represents the timeline of Mable’s reactions when she starts a project she’s excited about. She starts out inspired and excited to use her current skillset and build upon it as she explores the challenge. When she faces the first challenge, she has motivation to figure it out on Google, and implement the solution herself. When she has a difficult time finding an answer she understands, she loses motivation and asks ChatGPT, which gives her an approachable and encouraging answer. She is re-inspired and now uses ChatGPT in for all her questions. Though, the more she uses it, the more comfortable she is with using the direct code output without fully understanding what it does. This makes her feel guilty, but the urgency of finishing the project is the priority.

Figure 14. Mable’s persona and journey map.

We chose these three personas because these personas focus most on the “typical” student — we have all been the shy or tired student at some point in our lives. These emotional journeys reflect throughout each persona, and these three personas capture the focus of our project.