BASELINE STUDY SYNTHESIS

Study Overview

Our baseline study was designed to establish a clear starting point for how college students currently plan their days and why their plans often fall apart once the day begins. The goal was to understand daily planning as it’s actually lived: messy, flexible, emotional, and shaped by unpredictable interruptions, rather than treating inconsistency as a personal failure. Specifically, the baseline aimed to capture (1) participants’ existing planning systems and assumptions, (2) what “sticking to a plan” means to them, and (3) the gaps between intention and execution that we later observed during the diary study. This baseline context was essential so that we could interpret the diary entries not as isolated moments, but as part of each participant’s broader habits, constraints, and mindset around planning.

Study Methodology

We used a mixed-method baseline approach, combining a short screener + baseline survey with a baseline pre-study interview, before launching the 5-day diary study. The pre-study interview included open-ended responses about how participants plan, what typically disrupts their plans, what motivates follow-through, and how they emotionally respond to missed tasks.

This baseline then fed into the diary study structure, where participants completed three daily check-ins for five days (morning intention-setting, midday progress update, evening reflection). Data collection occurred digitally using texts and voice notes via iMessage. The diary prompts were intentionally designed to capture both logistical outcomes (such as what was completed) and reflective context (such as what helped, what got in the way, how it felt emotionally), allowing us to directly compare intentions vs. reality across time.

Participant Recruitment

We recruited current college students because students frequently plan but operate in highly variable environments: classes, deadlines, fatigue, social plans, and shifting priorities constantly reshape the day. Participants were eligible if they:

- Were enrolled in college

- Had access to a smartphone or laptop (to complete check-ins)

- Used any form of daily planning (calendar, notes app, paper, etc.)

- Could commit to brief check-ins 3x/day for 5 days

Recruitment was conducted through peer outreach, prioritizing students who self-identified as people who “plan often” but don’t always follow through (who experience the intention–action gap firsthand) and also people we are personally close with. This allowed us to study real planning breakdowns rather than only highly disciplined planners.

Key Research Questions

The baseline study aimed to answer a set of foundational questions that directly shaped the diary study and our later synthesis:

- How do students decide what to plan for the day?

(What gets written down vs. kept in their head; how they prioritize tasks.) - What helps or prevents students from following through on their plans?

(Barriers like fatigue, distraction, perfectionism, schedule changes, and competing demands.) - How do students respond when plans change during the day?

(Whether they adapt, abandon, re-plan, or spiral into guilt/avoidance.) - How do students emotionally experience “consistency” and “falling behind”?

(Motivation, stress, self-judgment, relief, and how emotions affect action.) - What moments or conditions increase follow-through?

(Positive drivers: productive times of day, supportive environments, momentum, visible progress – added intentionally to avoid studying failure only.)

Together, these baseline questions established the context needed to interpret diary entries as part of a broader behavioral system: how intentions form, how they collide with reality, and what patterns govern follow-through over time.

RAW DATA -> GROUNDED THEORY

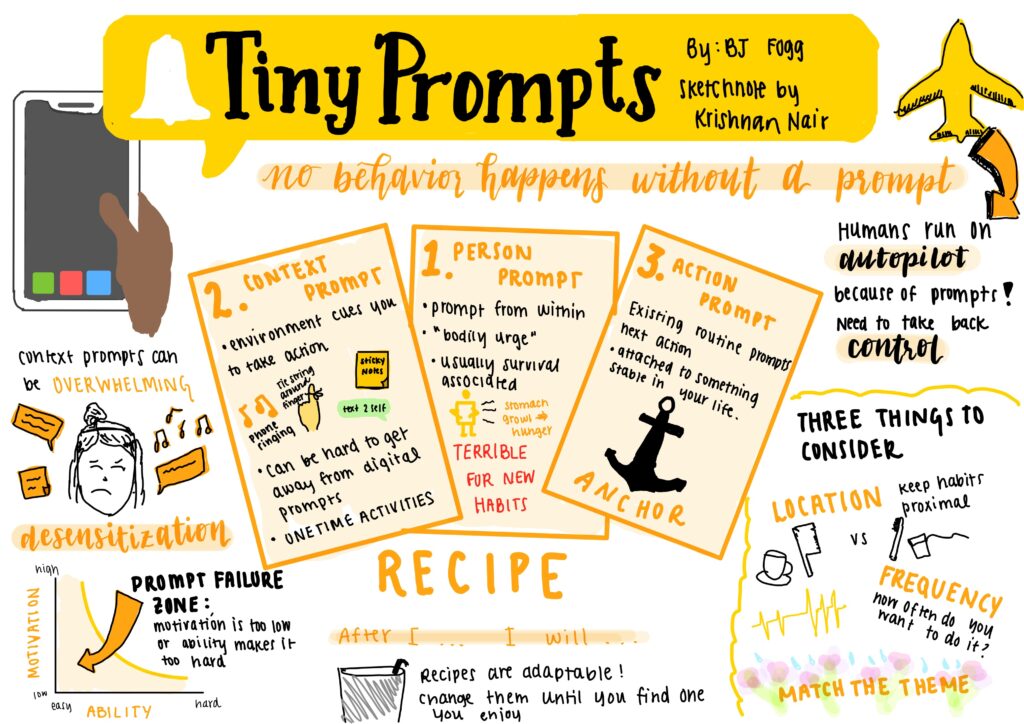

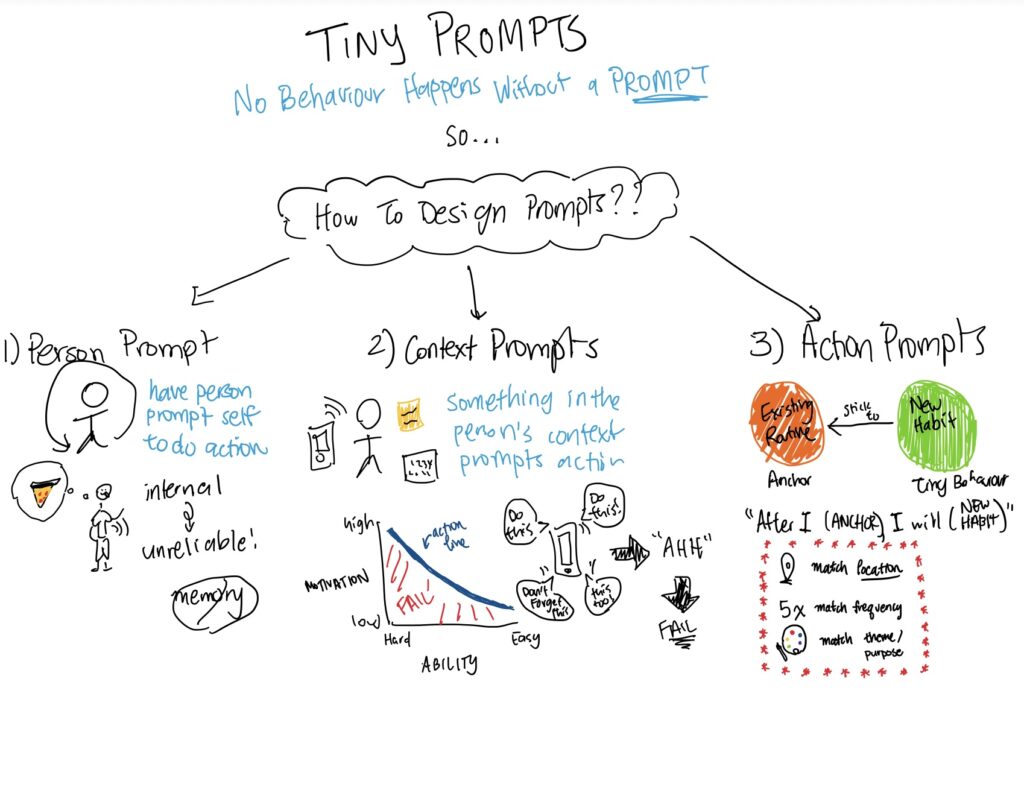

Fig 1: Affinity grouping to organize our findings

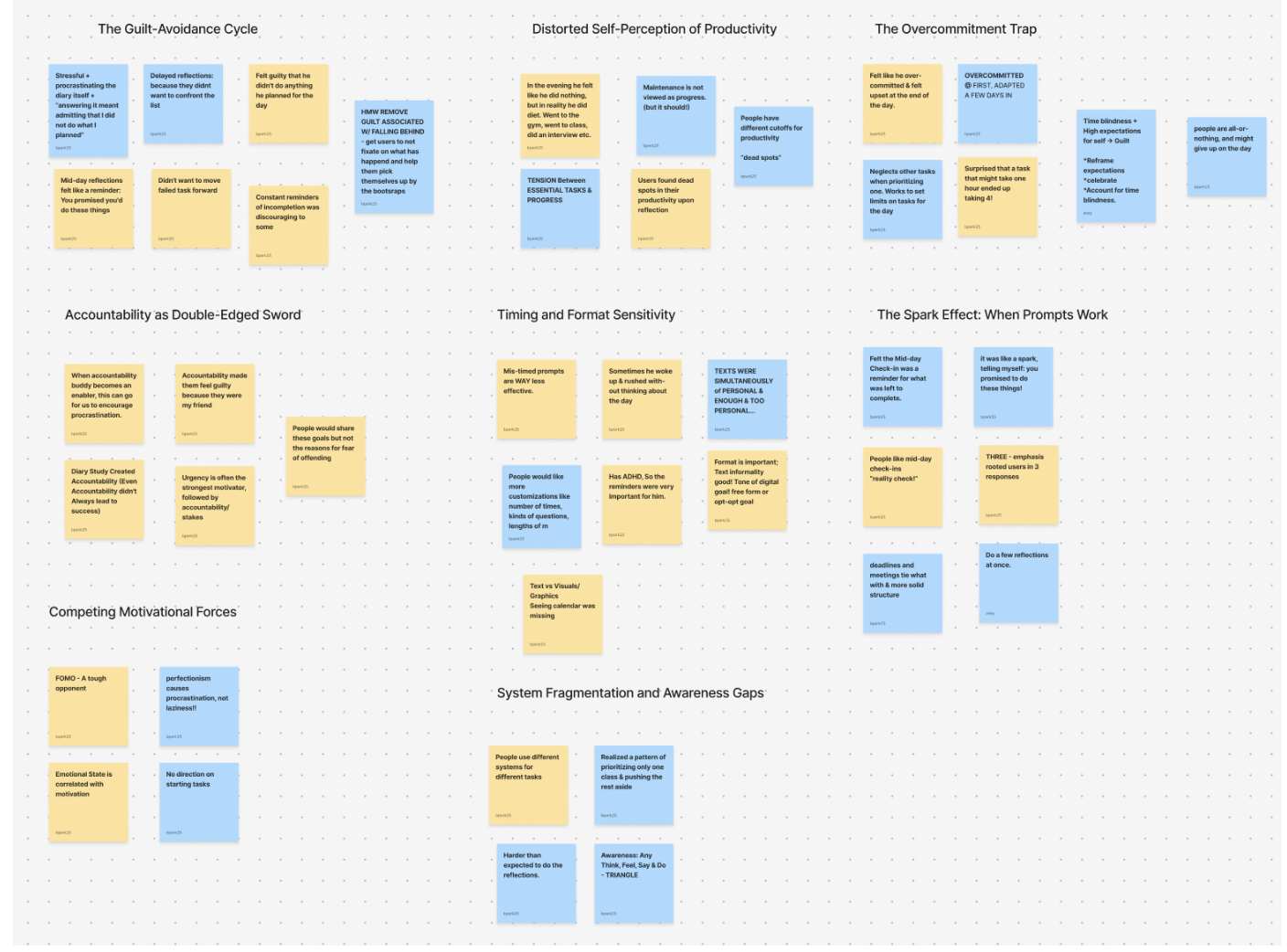

Grounded Theory #1: Overcommitment is a Trap

-

- Students can easily fall prey to time blindness and high expectations for themselves. They push themselves to do as much as they can, but can underestimate how much time each of their commitments will take.

- By the time they realize they’ve overcommitted, it’s already too late.

- Having to push back priorities or cancel commitments leaves students feeling upset and guilty.

- Perhaps we can combat overcommitment by reframing students’ self-expectations, helping them anticipate time blindness, and celebrating when students set themself up for success.

Grounded Theory #2: The Spark Effect (When Prompts Work)

- A reality check during the day can help reestablish priorities and realign plans with goals

- For several subjects, the mid-day check-in served as a reminder for what was left to complete and that the remaining tasks were things the student actually wanted to get done: “You promised to do these things!”

- Constraining reflections to short responses rooted in a few goals was received positively.

Grounded Theory #3: Distorted Self-Perception of Productivity

- Students don’t always have an accurate understanding how how productive they have been and when they are most productive.

- Tension between essential tasks and progress → Some productivity “doesn’t count” in some student’s eyes because it wasn’t one of their essential tasks. They feel they have been unproductive but really they were just doing things they didn’t count as productivity.

- Maintenance/Self-care are not viewed as progress

- Dead spots → Reflection helped students spot parts of their day when they weren’t productive.

- Tension between essential tasks and progress → Some productivity “doesn’t count” in some student’s eyes because it wasn’t one of their essential tasks. They feel they have been unproductive but really they were just doing things they didn’t count as productivity.

Grounded Theory #4: Timing and Format Sensitivity

- There were tradeoffs with the format of routine text we chose for our study

- Pros:

- Informality and brevity

- Responses could be freeform text or audio recording.

- Cons:

- No visuals; not related to or integrated with their calendar.

- Pros:

- The uncanny valley of accountability

- The texts were written to sound personal but they were templated and scheduled at reoccurring intervals. For one student, this felt both too personal and not personal enough.

- Timing is everything

- A mis-timed prompt is easily forgotten or ignored. The student should be in a position to respond at the time of the prompt.

Grounded Theory #5: System Fragmentation and Awareness Gaps

- Students often use more than one system to keep themselves organized

- For example:

- Calendar for classes and events

- To-Do lists for tasks and things to “check-off”

- Memory for social events and self-care

- For example:

- (Related to time blindness) students can miscalculate their ability to prioritize appropriately and gauge task difficulty

- One student identified a pattern of prioritizing only one class and pushing the rest aside

- Another found it harder to do the reflections for our study than they realized.

Grounded Theory #6: The Guilt-Avoidance Cycle

- Student fails to complete tasks → Student feels guilty for not doing anything they planned to do → Student feels avoidance about admitting that they didn’t complete their tasks → Student avoids diary study check-ins to avoid feeling bad about not completing their tasks → Student doesn’t reflect/recalibrate plans through diary study check-ins → Student continues to fall behind →

Repeat!

- If we can remove the guilt associated with falling behind, we could help students avoid fixating on what has happened and help them pick themselves up by their bootstraps

Grounded Theory #7: Accountability as a Double-Edged Sword

- Accountability garners an emotional response, but that doesn’t always translate to success

- Some students felt bad about missing diary check-ins, but that feeling didn’t lead to them changing their behavior in any way to ensure they didn’t miss future check-ins

- Having an accountability system can encourage offloading the responsibility of motivation to the system.

- If the system/buddy fails to keep the student accountable, then it’s easy to say that it was the system/buddy’s fault that the student didn’t get their tasks done.

- Friends as accountability buddies can lead to guilt if the student lets their friend down.

Grounded Theory #8: Competing Motivation Forces

- Desire to be productive clashes with FOMO, and FOMO is a tough opponent.

- Perfectionism causes procrastination, not laziness!

- The student’s current state has a big impact on their motivation/ability to get things done

- Lacking direction on starting tasks created friction

- Emotional state is correlated with motivation

SYSTEM MODELS

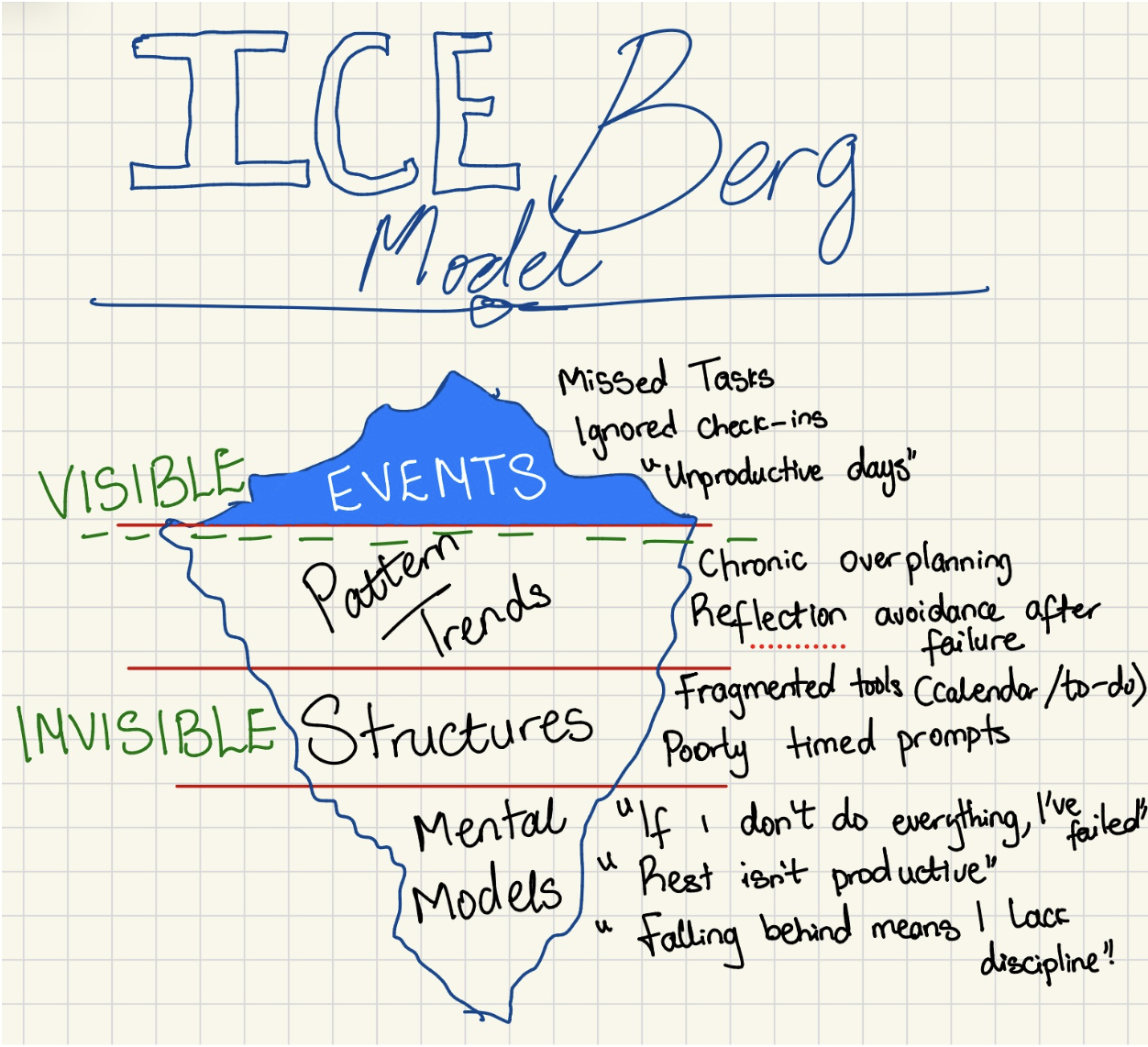

Fig 2: Iceberg System Model

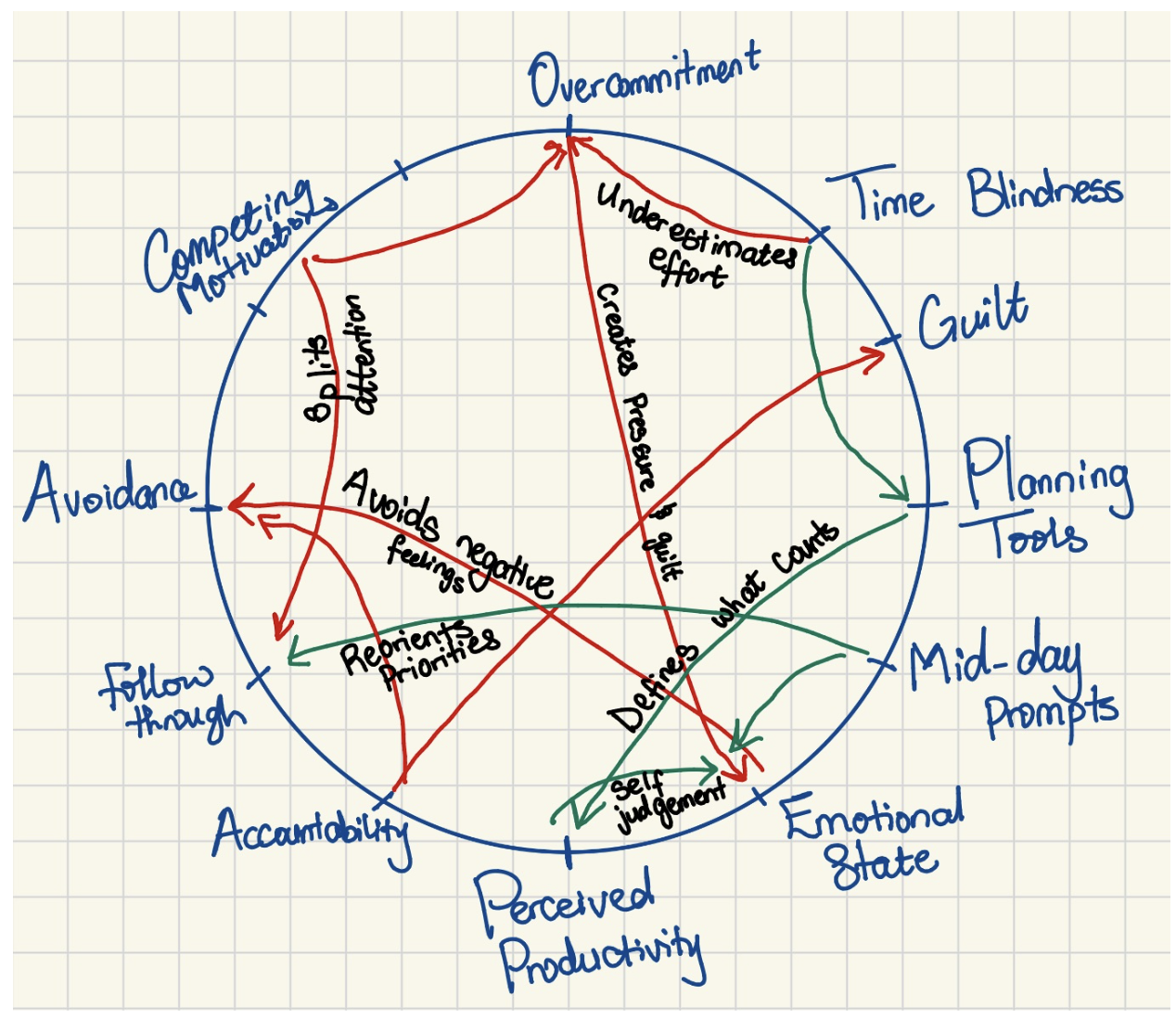

Fig 3: Connection Circle

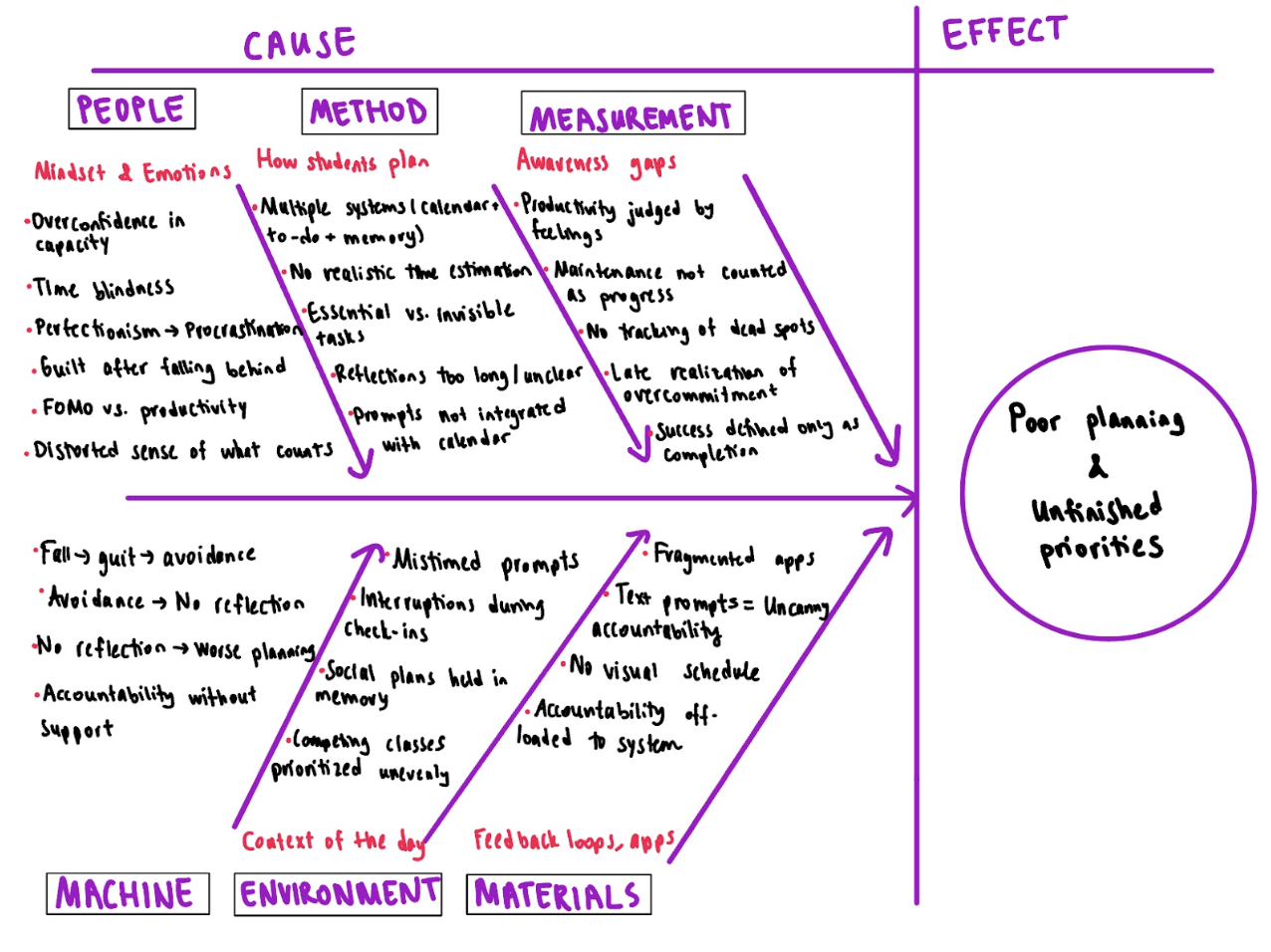

Fig 4: Fishbone Diagram

SECONDARY RESEARCH

Overall Trend in the Market Space

Across mainstream calendars (Google Calendar), flexible workspaces (Notion), and AI schedulers (Motion, Reclaim, Trevor, Lifestack), the dominant market pattern is clear: tools excel at capturing intentions and organizing time, but rarely help users follow through. Most competitors treat plan failure as a scheduling/optimization issue (“move tasks around,” “protect focus time,” “time-block better”) instead of a behavioral reality driven by avoidance, perfectionism, guilt spirals, distraction, and unpredictable contexts, especially for students.

This gap is reflected in our 2×2 map (Integration × Accountability). Tools cluster into:

- High integration, low accountability (Google Calendar, Notion, Todoist): great for logging and syncing, weak at creating behavioral pressure or learning loops.

- High integration, higher accountability (Motion, Reclaim, Sunsama, Lifestack): add automation/structure, but still don’t deeply explain why users miss commitments.

- Low integration, higher accountability/engagement (Finch, Forest): strong motivation mechanics, but not embedded into real scheduling infrastructure.

This leaves a key gap: high integration + meaningful accountability that is behavior-aware (not punitive or sterile).

Key Insights from Comparator Analysis

1) Integration is table stakes, but it doesn’t create follow-through

Google Calendar and Notion show that low-friction capture and cross-platform integration make planning effortless, yet users still flake because calendars don’t support the execution layer: reflection, “why it failed,” and recovery planning. Even when Notion adds context, its complexity creates friction that can increase avoidance rather than reduce it.

Implication: Our solution should sit on top of existing calendars (or plug into them) instead of asking users to migrate, but must add the missing “behavior layer.”

2) “Accountability” in most tools = reminders or rigid automation and not behavioral support

Motion/Reclaim/Lifestack/Trevor introduce scheduling intelligence, but their notion of accountability is mostly:

- warnings about overcommitment

- auto-rescheduling

- defended focus blocks

- productivity-style optimization

However, users’ actual failure modes are emotional resistance, perfectionism, and context shifts. Finch/Forest prove motivation design works, but they operate outside calendar reality.

Implication: We should design accountability as supportive + reflective (helps users start, recover, and learn), not just nagging.

3) Feedback loops are missing or passive across the entire space

Most tools show outcomes (“overdue,” “missed,” “rescheduled”) without asking:

- What got in the way?

- Was the plan unrealistic?

- Was this low-energy time?

- Did perfectionism/avoidance show up?

- Is this a repeating pattern?

Sunsama comes closest with reflections and analytics, but is priced and framed for high-intensity professionals, less aligned with college students and “soft commitments.”

Implication: Our differentiator should be a simple learning loop: micro-reflection + pattern detection → better future planning.

Key Insights from Literature Review

1) Plans work when they are implementation-ready, not just recorded

Behavior research on implementation intentions and MCII shows that follow-through improves when people convert goals into specific if–then plans and anticipate obstacles. Importantly, the MCII meta-analysis suggests that self-directed written plans can be low-quality without guidance, reducing effectiveness, meaning it’s not enough to “write it down.” Users need scaffolding to generate usable plans.

Design implication: Build prompts that help users produce high-quality, context-aware intentions, not generic tasks (such as “If it’s 3 pm in the library and I feel stuck, then I will do 10 minutes of [small starter step].”).

2) Consistency comes from routines and context, not motivation

Routine research emphasizes that long-term adherence depends less on willpower and more on embedding behaviors into repeatable structures. Meanwhile, student daily-activity studies show that schedules are shaped heavily by institutional constraints, travel/time budgets, and spontaneous social activity, meaning consistency is often an environmental design problem.

Design implication: Support users in creating repeatable planning rituals (daily/weekly patterns) that fit real student rhythms, instead of relying on motivation or rigid plans.

3) Distraction and delay are context-dependent

Smartphone studies show that distraction and task delay vary within-person depending on context, and that different use patterns (fragmented vs sticky) can lead to different types of self-regulation failure. This supports our diary-study approach, that it’s situational.

Design implication: Trigger interventions based on moments of vulnerability (energy dips, avoidance cues, sticky phone loops), not generic reminders.

4) Productivity tools can increase guilt and anxiety if they only measure “failure.”

Work on busyness and productivity tools shows that these systems can reinforce identity-based pressure (“I’m behind,” “I’m not disciplined”) and reduce perceived autonomy. Our own participant data echoes this: reflection can be helpful, but too many questions can become stressful and avoided.

Design implication: Feedback should be non-judgmental and autonomy-supporting (learning-oriented, not guilt-oriented), and extremely light.

How This Influences Our Ideation Phase

Based on these trends and findings, our ideation will focus on building a behavioral layer that sits on top of existing planning systems, targeting the intention-action gap directly. Specifically, we may explore concepts that:

- Add “soft commitment” support: differentiate between “aspirational” vs “must-do” commitments and design different follow-through mechanisms accordingly.

- Scaffold high-quality planning (implementation intentions / MCII): help users turn vague plans into executable next steps + obstacle plans, without increasing cognitive load.

- Create light reflection + recovery loops: micro check-ins that capture why something failed and convert it into a better future plan (without shame).

- Balance accountability with autonomy: supportive nudges, celebration, and pattern feedback rather than punishment or inflexible automation.

- Use context-aware timing: interventions tied to routines, energy patterns, and moments of vulnerability (distraction, avoidance, low-energy blocks).

PROTO – PERSONAS

https://highercommonsense.com/cs247b/behavioral-personas-journey-maps-raggiana-2/

BEHAVIORAL PERSONA

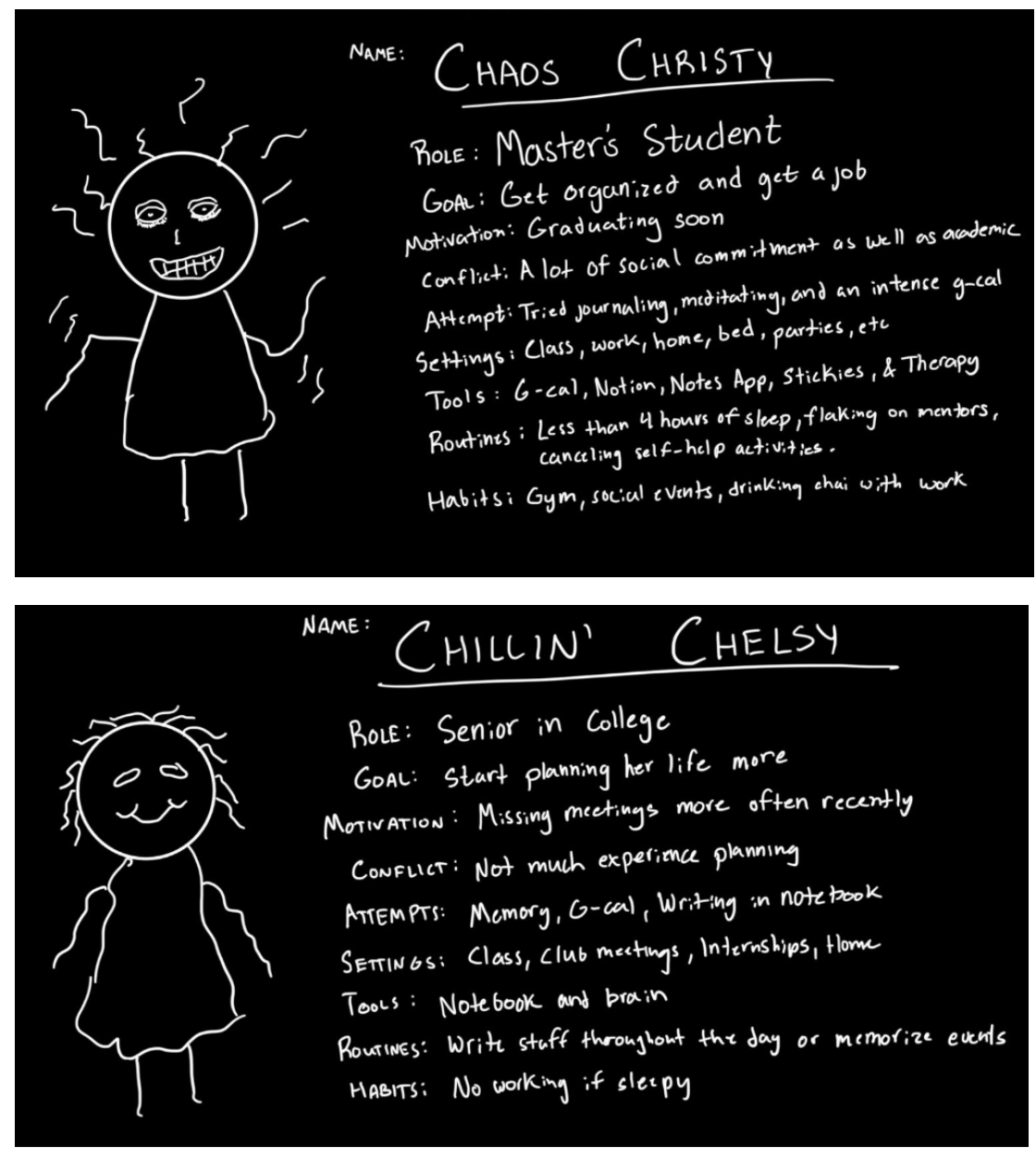

1) Chaos Christy

Overcommitted graduate student juggling academics, job search, and heavy social life. Uses many digital tools (G-cal, Notion, notes) yet lacks routines and sleep, causing cancellations and dropped commitments. Motivation exists, but structure is weak – accountability is externalized to tools that don’t truly guide behavior.

2) Chillin’ Chelsy

Low-structure, low-stress planner who relies mainly on memory and a notebook. Wants to plan more but lacks experience and urgency. Works only when energy feels right (“no working if sleepy”), so progress is inconsistent. Few systems, minimal conflict, but limited forward momentum.

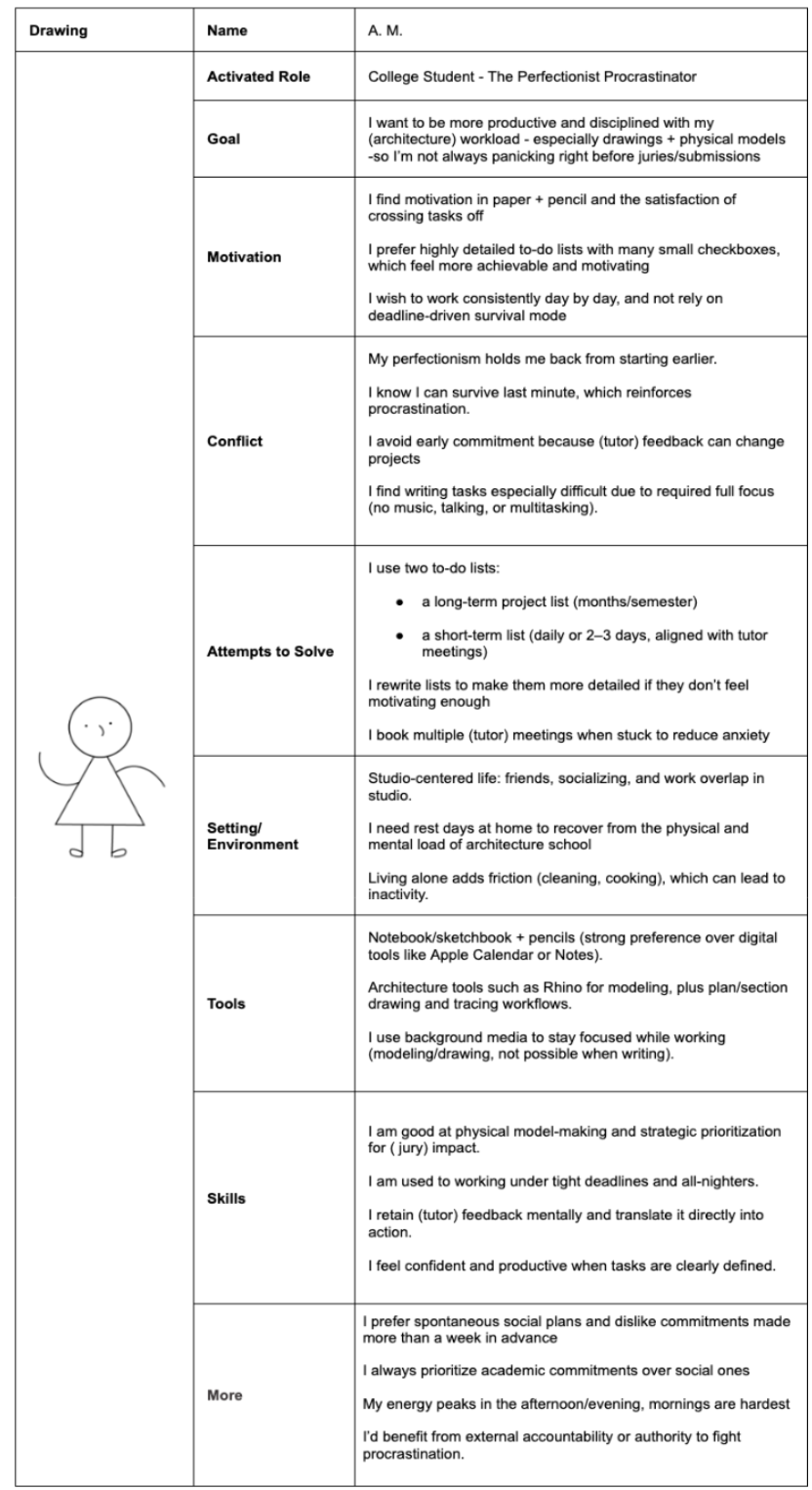

3) The Perfectionist Procrastinator (A.M.)

A student driven by high standards and craft pride, especially in hands-on creative work. They are motivated by detailed, paper-based to-do lists and the satisfaction of crossing items off, but perfectionism delays starting early. Feedback dependency and fear of rework lead to last-minute “survival mode.” Studio life blurs social and academic boundaries, and fragmented systems (calendar + lists + memory) create friction despite strong skills and discipline under deadlines.

Shared Themes Across Archetypes

- Fragmented planning systems → misjudged time & priorities

- Motivation ≠ execution; environment and routines dominate

- Emotional factors (perfectionism, guilt, energy) shape behavior more than tools

- Need for simple, integrated, low-friction structure

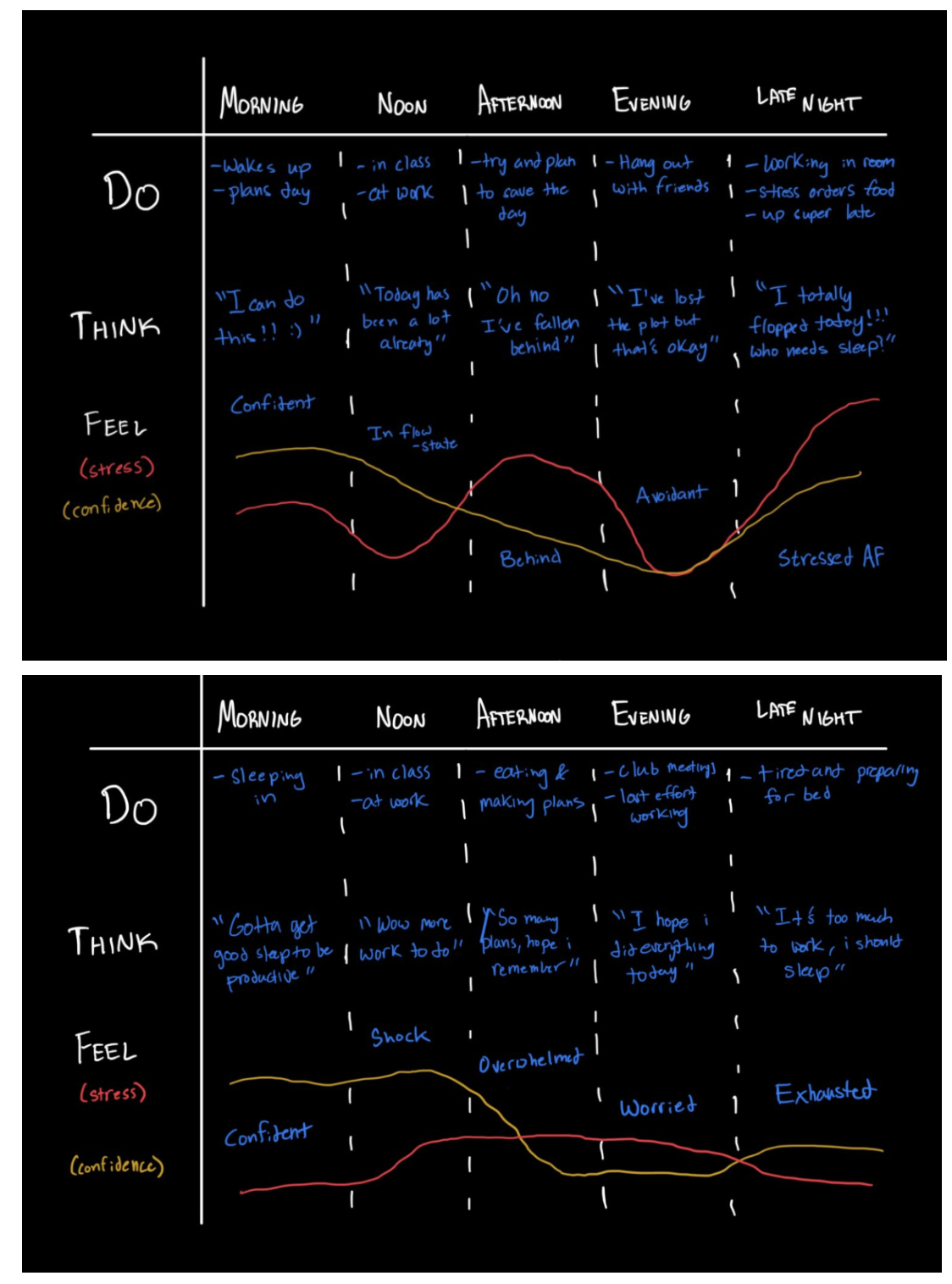

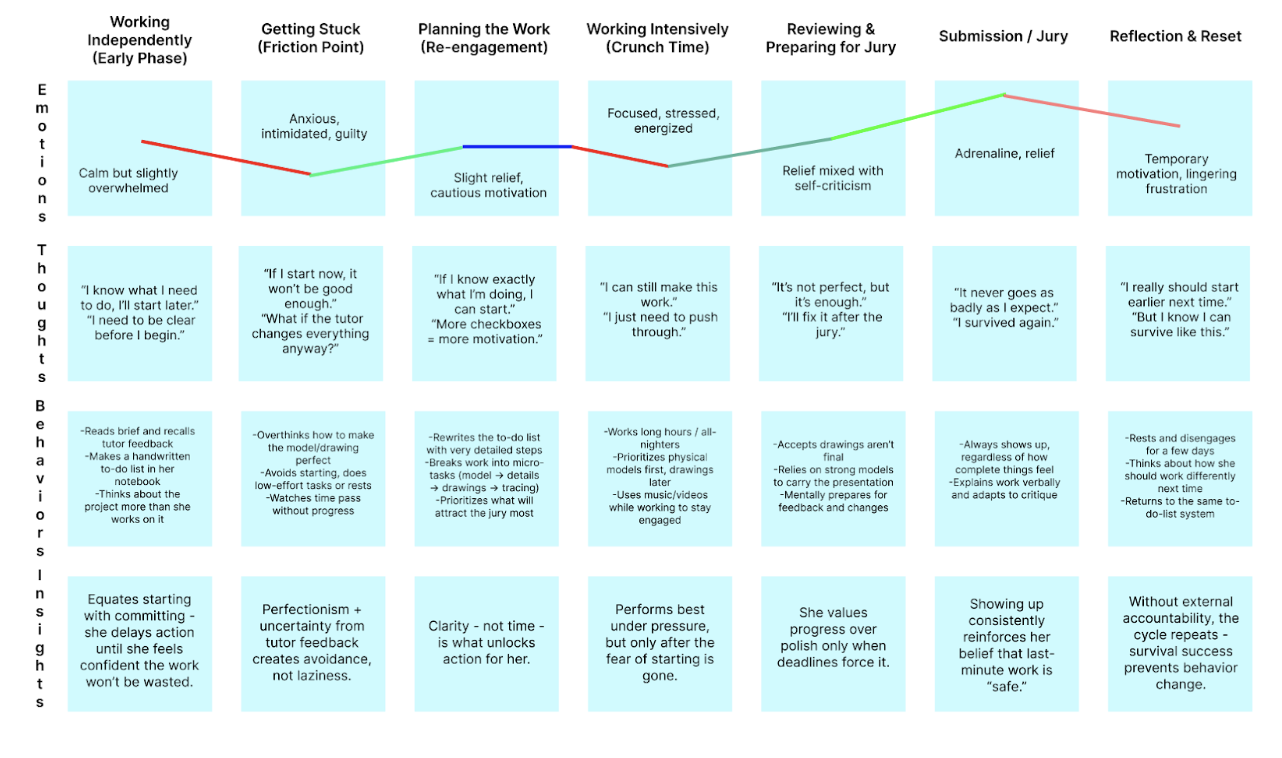

JOURNEY MAPS

Our journey maps illustrate how students’ productivity fluctuates across the day and across longer project cycles, showing that behavior is driven more by emotions and context than by intention. The daily maps reveal a repeated pattern: mornings begin with optimism and planning, confidence declines as tasks accumulate, and evenings often shift into avoidance or last-minute “rescue mode,” where stress rises while confidence drops. The longer project timeline map shows a similar arc – early phases are marked by calm overthinking, the middle by anxiety and re-engagement, and the end by intense crunch followed by relief and self-criticism. Across both views, we see that perfectionism, unclear starting points, and fragmented systems delay action, while deadlines temporarily override fear without changing the underlying cycle. In conclusion, the maps highlight that productivity is less about motivation and more about how thoughts, feelings, and environments interact over time.