Baseline Study

We are Team Monkey, a group of undergraduate students who are motivated to help improve posture habits around campus! Our five members include Akanshya Bhat, Mena Hassan, CJ Indart, Christelle Millos-Lopez, and Abena Ofosu. We created Postura, an application and wearable device that can help you and your friends improve your posture together, earning rewards and prizes for group and individual success! To get started on our project, we conducted a baseline study, which is outlined below.

Baseline Study

Understanding the daily posture habits of university students was the first step in designing an effective intervention. This section provides an overview of the baseline study we conducted to explore how students engage with their posture in various environments. The insights gathered from this study informed the development of our intervention strategies aimed at promoting better posture.

Study Overview:

This baseline study aimed to examine how university students engage with and maintain their posture throughout the day. It took the form of an observational approach to identify the factors contributing to poor posture, as well as participants’ awareness and habits related to posture. The key objectives were:

- Measure the frequency and context in which participants engage in poor posture

- Assess participants’ awareness of their posture and the effectiveness of reminders in improving it

- Identify common situations, behaviors, and environmental factors that contribute to poor posture

Study Methodology:

This study was conducted over five days, during which participants received three daily text reminders prompting them to reflect on their posture. Additionally, they completed an end-of-day diary entry through Google Forms. Together, the text reminders and EOD form documented:

- Their posture at different times of the day

- The duration they remained in certain positions

- Any discomfort or pain they were experiencing

Post-study interviews were conducted to gain deeper insights, allowing participants to share their thoughts and personal experiences regarding their posture habits, challenges, and the impact of the reminders. The study collected quantitative data (posture frequency, duration, pain levels) as well as qualitative data (reflections on posture habits and awareness).

Participant Recruitment:

Participants were recruited from the Stanford University undergraduate student population because they represent a demographic that is both accessible and engages in academic and social environments where posture-related habits potentially impact well-being. We specifically considered whether they experienced posture-related pain or discomfort, as well as their ability to participate in a five-day study requiring frequent self-reflection. The accessibility of undergraduate students along with their vast personal networks allowed for efficient data collection and engagement. Additionally, undergraduates often have to balance long hours of studying, screen time, and various physical activities, providing us with an accessible group to examine posture-related behaviors and their effects. By focusing on this population, we aimed to gather meaningful insights that could point us toward potential interventions or behavioral adjustments applicable to similar student groups and young adults in professional settings.

Key Research Questions:

- How often do participants engage in poor posture throughout the day?

- In what specific contexts (e.g., studying, socializing, exercising) does poor posture most commonly occur?

- Do regular reminders effectively increase awareness and encourage self-correction?

- What factors – both environmental and behavioral – contribute to maintaining or failing to maintain good posture?

- How do participants perceive their own posture, and does their participation align with their actual habits?

Below, we dive into insights and key findings from the completed baseline study.

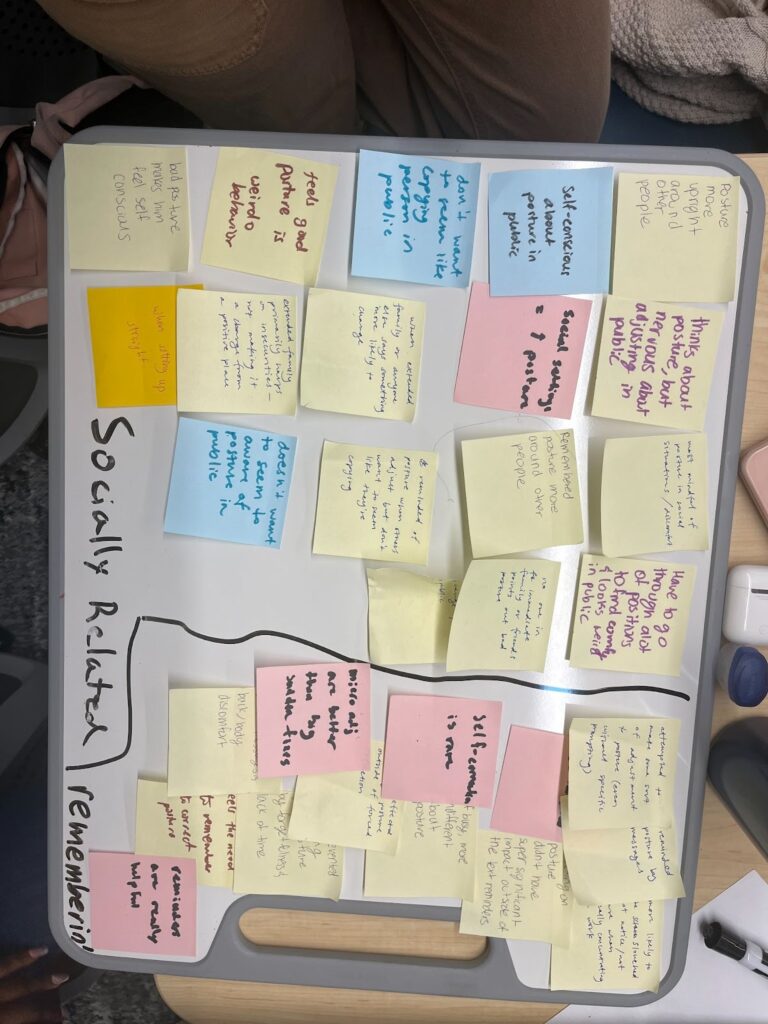

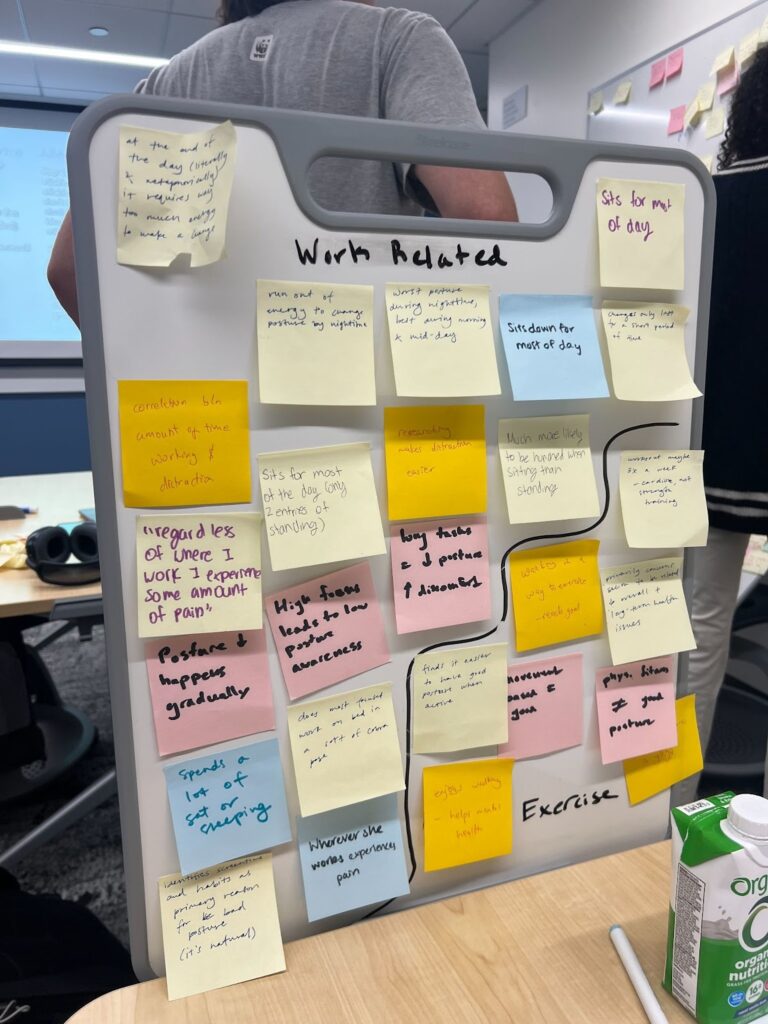

Raw Data → Grounded Theory

Once we gathered the data from our baseline study, we used grounded theory to identify recurring themes and patterns. Through pre-study interviews, daily study logs, and post-study reflections, we extracted key insights that formed the foundation of our theoretical framework. We identified seven major grounded theories, each highlighting distinct behavioral trends and underlying causes in posture-related habits.

Grounded Theory 1: People tend to be indifferent about their posture, especially when they are concentrating on other tasks, such as schoolwork.

- Subtheory 1.1: People prioritize task completion over physical comfort, leading to prolonged poor posture

- Subtheory 1.2: Individuals only become aware of poor posture when they experience discomfort or pain.

- Subtheory 1.3: Digital distractions (phones, laptops) exacerbate posture neglect by increasing screen time and reducing movement.

- Evidence:

- Contradiction/Tensions: Even when experiencing discomfort and becoming aware of bad posture, individuals continued to prioritize task completion

Grounded Theory 2: Most of our customers, undergraduate students, don’t seem to have a proper ergonomic set-up where they can do work.

- Subtheory 2.1: College dorms and libraries prioritize space efficiency over ergonomic design.

- Subtheory 2.2: Students often work in multiple locations (cafés, libraries, beds) rather than a designated workspace.

- Evidence:

- Contradiction/Tension: A lot of university students have no control over the ergonomics of university-provided furniture.

Grounded Theory 3: People are self conscious about bad posture, but also self conscious about fixing their posture in public.

- Subtheory 3.1: Fixing posture in public (e.g., stretching, adjusting chair position) can draw unwanted attention. People fear being perceived as “overly concerned” with appearance when correcting posture.

- Subtheory 3.2: Social norms reinforce a “natural” sitting or standing posture, making exaggerated corrections seem awkward and weird.

- Subtheory 3.3: Peer influence can determine posture habits. If others slouch, individuals feel less pressure to sit upright.

- Evidence:

- Contradiction/Tension: Although good posture is desired, nobody wants to be seen “fixing” it in public

Grounded Theory 4: Movement helps with improving posture but just because you workout doesn’t mean you have good posture.

- Subtheory 4.1: Some workouts strengthen muscles but do not address posture habits.

- Subtheory 4.2: Weightlifting without proper form can reinforce poor posture instead of correcting it.

- Subtheory 4.3: Activities like yoga and pilates focus on posture awareness more than strength training does.

- Evidence:

- Contradiction/Tension: People are conflicted on whether or not working out helps with posture, but research shows that you need muscular strength to maintain good posture.

Grounded Theory 5: People are generally more likely in the morning to fix their schedule and run out of motivation and willpower in the evenings or the end of the day.

- Subtheory 5.1: Decision fatigue reduces people’s ability to maintain good habits throughout the day.

- Subtheory 5.2: Morning routines create a sense of structure, whereas evening routines are more relaxed and prone to slouching.

- Evidence:

- Contradiction/Tension: People have different routines and some people don’t even have the willpower to change their postures in the mornings.

Grounded Theory 6: People spend most of their day either sitting or sleeping, and tend to have worse posture in these positions than when standing.

- Subtheory 6.1: The convenience of soft furniture (beds, couches) promotes slouching and poor posture.

- Subtheory 6.2: People prioritize comfort over ergonomics, leading to poor sitting habits.

- Evidence:

- Contradiction/Tension: N/A (Everyone we interviewed came to a consensus on these points)

Grounded Theory 7: Reminders seem to help with fixing posture, but are most effective early in the day and only remind them for a moment.

- Subtheory 7.1: Frequent reminders lose their effectiveness over time due to desensitization (because people start ignoring notifications).

- Subtheory 7.2: Reminders that incorporate feedback (like tracking progress over time) may be more motivating than random one-time alerts.

- Evidence:

- Contradiction/Tension: Different people have different effects from reminders – some people never react to a reminder while others always do. Most are in the middle, as described above.

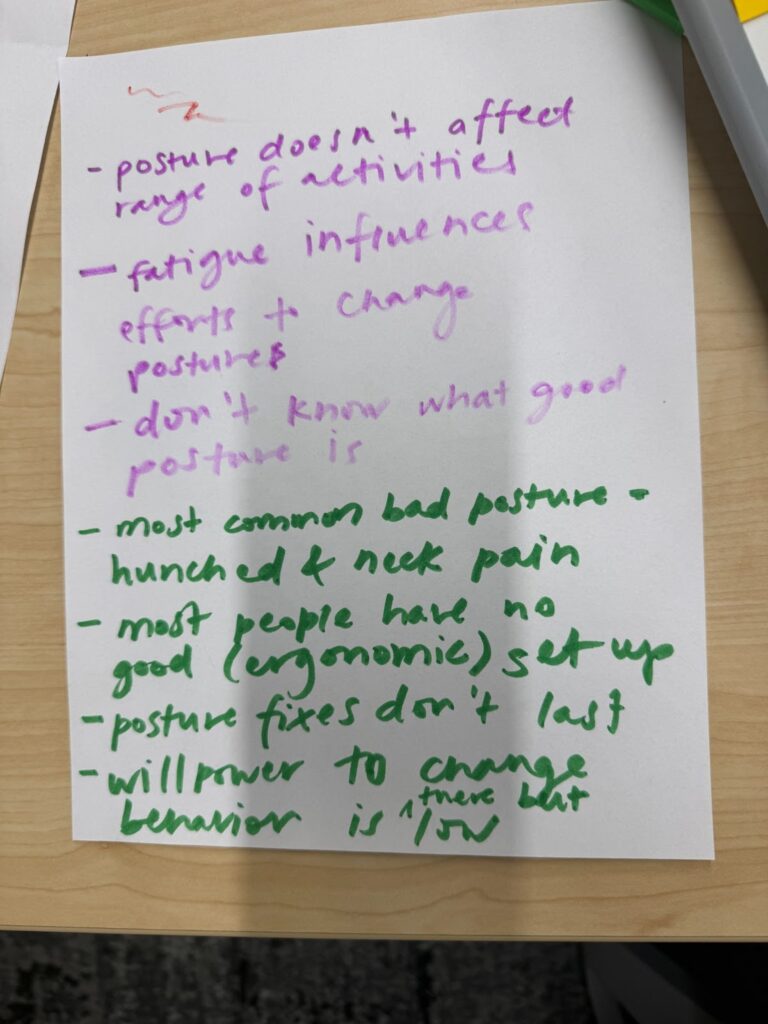

Photos:

Transcript:

- Posture doesn’t affect range of activities

- Fatigue influences efforts to change posture

- Don’t know what good posture is

- Most common bad posture – hunched & neck pain

- Most people have no good (ergonomic) set up

- Posture fixes don’t last

- The willpower to change behavior is there but low

Transcript:

- Easy to forget about posture when busy/concentrating on other things

- Sometimes indifferent even when people do notice

- Easier to make small adjustments that take less effort

- Fixed posture when reminded, but behavior usually doesn’t persist

- People are self-conscious about bad posture but also self-conscious/think it looks weird to fix posture in public

- Sits up straight whenever people tell them to but sometimes family members do it in a way that harps on insecurities

- People want to have good posture but also seem nonchalant in public

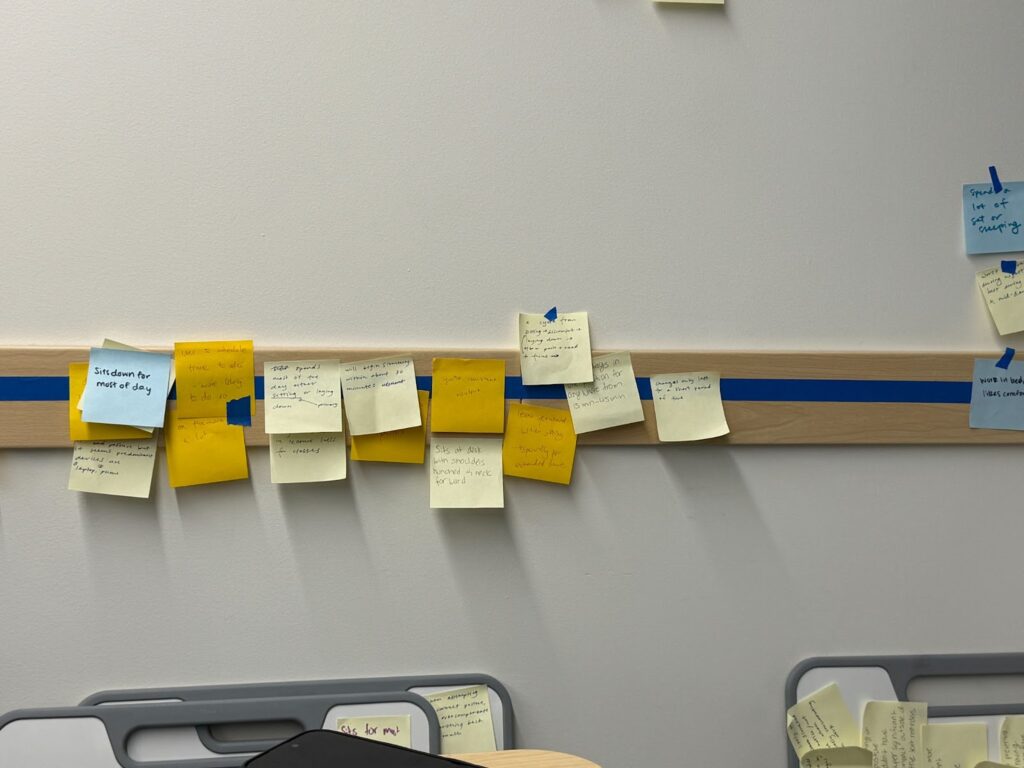

TIMELINE:

Start of day:

Middle of day:

End of day:

Once we had all of these grounded theories after our baseline study, we wanted to illustrate and model our insights to better understand how they all interact with one another.

System Models

Model Description: This model maps how different daily activities influence posture, categorizing them into morning, early afternoon, late afternoon, and evening. Green arrows indicate activities that increase slouching, while red arrows indicate activities that help decrease it. Notably, checking the phone, working on homework, and lying on the couch contribute most to slouching, whereas getting ready, meeting with people, and walking to class improve posture. This model highlights key moments where interventions could be most effective.

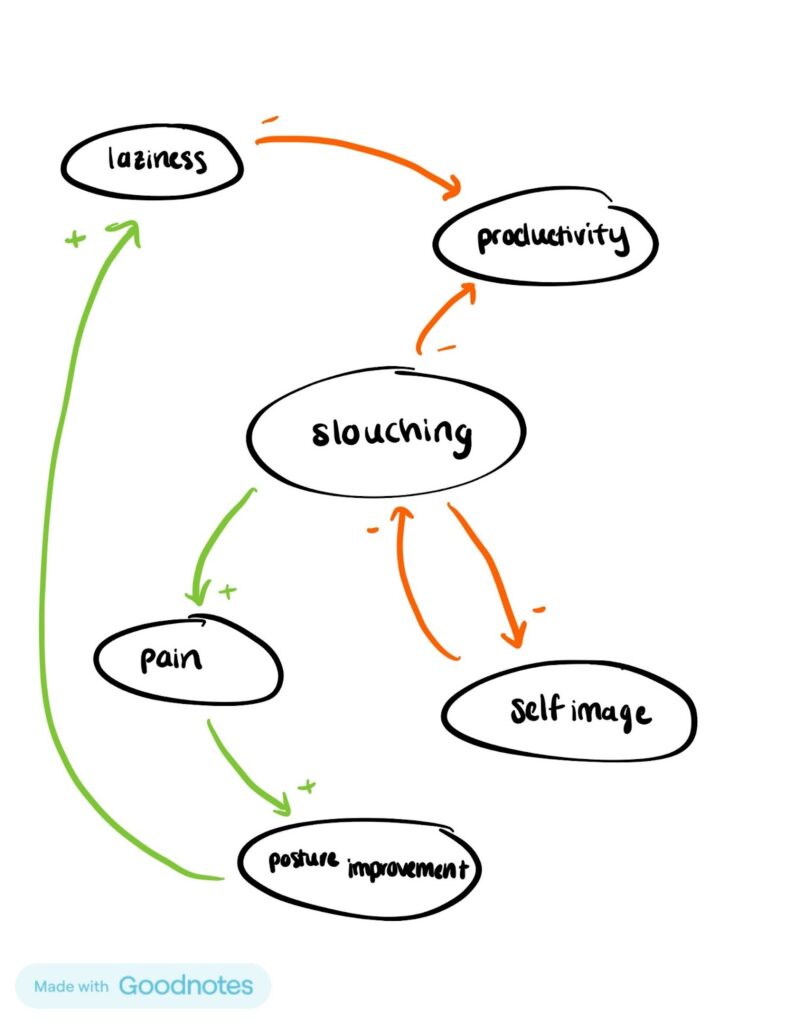

Model Description: This causal loop diagram illustrates the relationships between slouching, productivity, pain, laziness, posture improvement, and self-image. Slouching negatively impacts productivity and self-image, while pain from slouching can eventually lead to posture improvement. Interestingly, laziness contributes to slouching, but increased pain from poor posture can push individuals toward corrective actions. This model emphasizes how multiple psychological and physical factors interact to influence posture habits.

From our Grounded Theory analysis, we identified several behavioral patterns related to posture, including indifference towards posture, the influence of social perception, and the impact of daily routines. These insights helped us construct system models that visualize the deeper structures underlying posture-related behaviors.

Our system models encompass the main themes we saw across the different needfinding interviews we conducted (pre-study and post-study interviews). We saw how people tended to slouch due to common habits: checking their phones, relaxing on their couches/rooms, and working on homework. A main perpetrator of bad posture was the use of electronic devices. However something that kept coming up was how dressing up affected their self-image which in turn affected their posture. People felt like they had to live up to their outfit, therefore they would improve their posture. This helped us realize that people cared about their appearance, especially in the presence of others. As people go through the day, they tend to do more activities that will cause them to slouch–a lot of them which they cannot avoid because it is part of their life as a student. This raises the question of how we can help them improve their posture without disrupting their daily routines.

Secondary Research (Literature Review + Comparative Analysis)

Literature Review

In this blog post, we listed 11 pieces of literature that have aided our study design and summarized the key findings from each of them. From our research, one key insight is that poor posture is not only pervasive across different age groups and contexts but also leads to a variety of health challenges, including neck pain, back pain, and musculoskeletal discomfort. Sedentary lifestyles—from prolonged computer use among engineering students to children sitting in school settings—exacerbate posture-related problems. Across all these articles, there is a consistent theme: without conscious efforts or interventions, prolonged poor posture can result in chronic pain and diminished quality of life especially in our target audience.

Another major finding is the diverse range of interventions that have been tested to address or correct posture issues. Exercise programs, for example, were effective at reducing pain by emphasizing posture awareness while feedback devices, such as posture correction belts, and forward head posture gadgets, helped users recognize and correct posture in real-time. All in all, the most benefit may be had in combining both physical and behavioral strategies for optimal posture correction.

Comparative Research

Through our comparative research (in detail here), in mapping out the various posture-focused solutions—from wearable devices like UpRight GO and Lumo Lift to service-oriented offerings such as chiropractors and massage centers—we discovered each competitor addresses a unique market gap. For instance, posture-correction wearables tackle the immediate feedback gap that workout apps fail to address, while chiropractic care caters to individuals who need in-depth, professional realignment that neither a device nor an app alone can effectively provide.

While each option addresses specific aspects of posture correction, none of them provide a fully comprehensive solution that simultaneously delivers real-time feedback, long-term muscular reinforcement, and personalized holistic care to completely resolve the user’s posture challenges. For example, UpRight GO delivers real-time posture alerts that the Perfect Posture & Healthy Back App lacks, ensuring immediate correction when users slouch. However, the device alone doesn’t strengthen core muscles over time, while the App’s workout approach relies heavily on user discipline and offers no instant feedback.

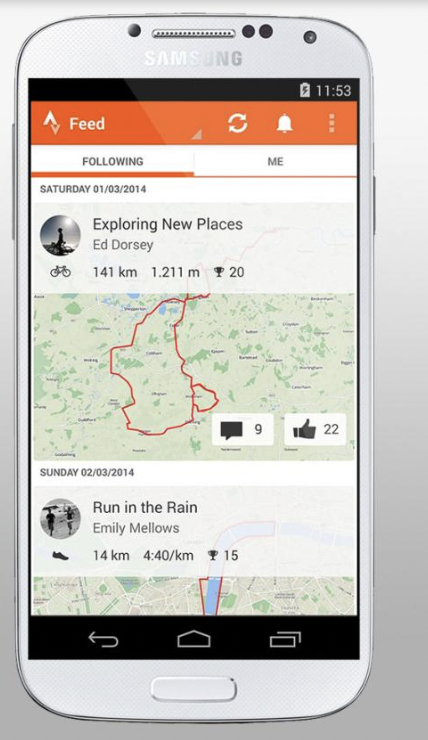

On the other hand, chiropractors offer targeted, professional musculoskeletal adjustments that Strava doesn’t, directly addressing structural issues behind poor posture. Yet depending solely on in-person care can be costly and sporadic, whereas Strava’s active lifestyle approach is beneficial but lacks individualized posture correction.

[pages from Strava]

Our 2×2 map also highlights convenience factors: digital apps reduce barriers for busy individuals, yet they often lack the hands-on monitoring provided by professional care or physical braces.

By plotting these solutions on our 2×2 matrix, we recognized a trend toward increasingly automated or AI-powered feedback mechanisms. However, cost and user-friendliness still pose significant hurdles—especially for products requiring repeated in-person appointments or premium subscriptions.

We decided that the axes should be inaccessible to accessible and physical to digital because there are significant differences in how posture solutions are delivered, their ease of access for users, and their reliance on either physical intervention or digital automation. These axes help illustrate the trade-offs between convenience, cost, and effectiveness, allowing us to better understand market gaps and position our solution accordingly.

Strengths of Competitors

- Real-Time Posture Feedback

- UpRight GO, Lumo Lift, AI Posture Reminder App

These competitors provide continuous, immediate alerts (vibrations or onscreen notifications) to help users correct slouching in the moment.

- UpRight GO, Lumo Lift, AI Posture Reminder App

- Holistic Professional Approach

- Chiropractors (e.g., Stanford Chiropractic Center)

Offers in-person evaluations and spinal alignments that address posture at its root causes, providing more comprehensive, medically informed solutions.

- Chiropractors (e.g., Stanford Chiropractic Center)

- Low Barrier to Entry

- PostureZone

Does not require additional hardware beyond a smartphone and is relatively affordable, making posture checks more accessible to a broad audience.

- PostureZone

- Aesthetic or Lifestyle Appeal

- Posture Pal Stuffed Animals, Copper Compression Brace

Provides a more “friendly” or discreet approach; users can incorporate posture support into everyday routines without feeling they’re wearing medical gear.

- Posture Pal Stuffed Animals, Copper Compression Brace

Weaknesses of Competitors

- Limited Accessibility & High Cost

- Chiropractors, Massage Centers

Require in-person visits or ongoing fees, making them less accessible to users who lack the time or resources to attend regular sessions.

- Chiropractors, Massage Centers

- No Real-Time Monitoring

- Perfect Posture & Healthy Back App, Strava

These rely on user self-discipline rather than giving continuous alerts; users may lose motivation or practice poor form between scheduled workouts or activity tracking.

- Perfect Posture & Healthy Back App, Strava

- Physical Intrusiveness or Discontinuation

- Copper Compression Brace, Lumo Lift

Braces can be uncomfortable or socially noticeable, while discontinued products like Lumo Lift offer limited support or updates.

- Copper Compression Brace, Lumo Lift

- Battery and Privacy Concerns

- AI Posture Reminder App, Strava

Continuous tracking can drain battery life; reliance on camera/GPS monitoring raises user privacy fears, potentially deterring consistent use.

- AI Posture Reminder App, Strava

Proto-Personas & Journey Maps

To humanize our data and design a user-centered intervention, we created proto-personas and journey maps that represent typical student experiences with posture. We selected two personas—Jacob, a student-athlete, and Valeria, a highly self-aware undergraduate—to highlight different challenges and motivations related to posture correction. The full list of personas are listed and linked here: Jacob, Valeria, Laith, Samantha, and Gibby.

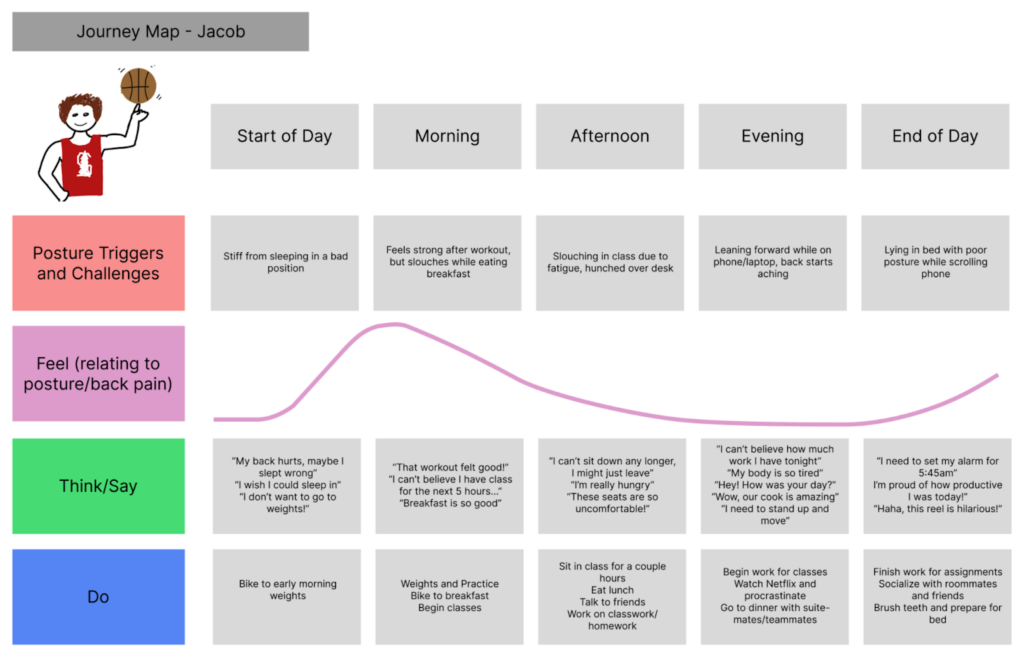

Jacob (blog post linked here, journey map figma linked here)

| Drawing | Name | Jacob Rueman (J.R.) |

|

Activated Role | College undergraduate student-athlete, basketball player |

| Goal | I want to fix my daily posture… | |

| Motivation | … because my bad posture becoming painful throughout the day, affecting my mood and physical abilities when in long classes, working, or exercising/lifting for my sport. | |

| Conflict | I am such a busy person, balancing college athletics along with school and having a social life that I find it hard to remember to fix my posture. It is also hard to stay in a good posture position when it is so unnatural to me, and I’m already tired a lot of the time. | |

| Attempts to Solve | I have tried to fix my posture when I remember or when I am having discomfort due to an unnatural sitting or standing position.

I have also worn a back brace during the school day, during practice, and during weights but it’s so uncomfortable and annoying. I have watched a few YouTube videos on posture correction but haven’t implemented any long-term strategies. I tried setting reminders on my phone, but I usually ignore them because I’m focused on other tasks. |

|

| Setting/ Environment | I notice my posture the most:

|

|

| Tools/Skills |

|

|

| Routines |

|

|

| Habits |

|

One of the personas that we chose was Jacob (aka JR). JR is a student-athlete who works out every day but still experiences bad posture and has problems with posture related to long work hours or extended phone and laptop usage for classes. He has a demanding schedule and finds it hard to remember to implement posture fixes throughout the day, losing awareness of the importance of sitting and standing in the correct position. Sometimes people assume that athletes and people who consistently work out automatically have good posture but this is not always the case, and JR is a representation of this.

It seems that JR’s posture is closely associated with his daily routines and habits, particularly the long hours spent sitting in class, studying, and carrying a heavy backpack while walking around campus. His demanding schedule leaves little room for conscious posture adjustments, and even when he tries to correct it, he often reverts back to slouching or leaning forward due to fatigue. While he has attempted solutions like using a back brace and setting personal reminders, these efforts have not led to lasting improvements. It is clear that JR’s posture struggle isn’t due to a lack of awareness but rather the difficulty of maintaining good posture amidst physical fatigue and a packed schedule. His experience highlights that traditional solutions like reminders and external supports may not be effective unless seamlessly integrated into daily life and routines.

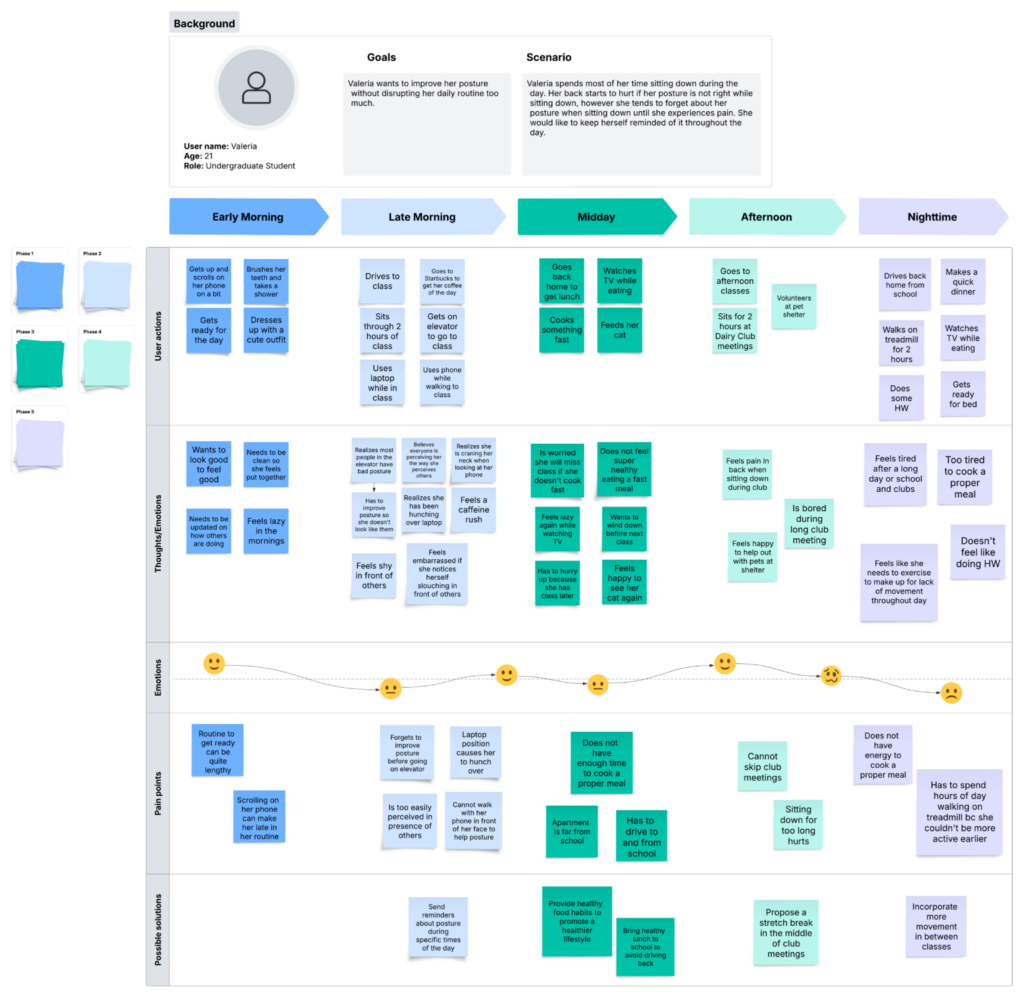

Valeria (blog post linked here, journey map file linked here)

| Drawing | Name | Valeria |

|

Activated Role | Undergraduate Student |

| Goal | I want to improve my posture | |

| Motivation | I don’t want to look ugly and feel unhealthy right now and later in my life | |

| Conflict | Wants to improve her posture but gets really lazy throughout the day and doesn’t do much to change her posture. | |

| Attempts to Solve | Attempts to remember to keep a good posture by being conscious of other people’s posture. She is constantly looking at others around her to help her remember that she has to correct her posture so she does not look like people who are slouching. | |

| Setting/ Environment | She mainly tries to solve her posture problem when she is around other people. Popular places in which she is most aware of others are in class, in the elevator, and during her club meetings. | |

| Tools | Does not currently own or use any inanimate tools to help her improve her posture. Closest to a tool that will help her improve her posture is her piano teacher that tells her to sit up straight when she is playing. | |

| Skills | Has a good memory that reminds her to improve her posture because she hears her grandmother’s voice in her head telling her to sit up straight. | |

| More | Routines: She has a pretty simple routine of driving to school from her apartment, going to class, going to her clubs, and then driving back to her apartment. She spends most of her time sitting down except for when she walks on the treadmill for 2 hours when gets back home. She tries to compensate for her lack of physical activity throughout the day by walking on the treadmill for hours on end.

Habits: She tends to lay around in her apartment a lot. She enjoys watching TV when she is back from school and does not have to do any work. She usually watches at least an hour of TV per day. During these moments she tends to relax and disregard her posture. She also observes people a lot and is wary about herself in the presence of others. She is always making sure she looks her best because she does not want to look bad in front of others. |

One persona we chose is an undergraduate student in West Virginia called Valeria. She is your typical undergraduate student that goes to class, does some homework, and goes to her weekly club meetings. However, she is also hyper aware of those around her, which provides some interesting insight into how she moves along throughout her day. Little things do matter to her, which makes her an interesting persona to study when it comes to posture. Her awareness of others serves her as a reminder to keep up her good posture, but what about when she is alone?

In her journey map, we see hints or subtle mentions of wanting to be healthier and feeling poorly about their posture. Both of these relate back to being perceived by others. Valeria is a relatively healthy individual except when it comes to some of her eating habits where she has to eat on the fly. However, this seems to affect her image as she wants to be seen as perfect as possible. This includes her dressing well and having good posture to live up to the outfit she is wearing. There seems to be a conflict at hand: Valeria wants to be as physically healthy as possible, but at the same time has trouble keeping up a healthy lifestyle. Can improving her lifestyle toward a healthier one be a solution to improving her bad posture habits? This is something we can figure out now thanks to this journey map that follows her throughout the day and tracks her thoughts and pain points.

Jacob and Valeria were chosen to represent key subsets of our target audience, each embodying unique challenges and motivations regarding posture correction. Jacob, a student-athlete, highlights the misunderstanding that physically active individuals and athletes naturally have good posture. His packed schedule and physical demands make it hard for him to maintain good posture throughout the day, regardless of his access to fitness resources like a trainer. On the other hand, Valeria represents a self-conscious undergraduate student whose posture concerns are closely tied to social perception. Her awareness of others serves as a motivator for maintaining good posture, but when alone, she struggles to sustain healthy habits. By selecting these two personas, we aimed to explore both the physical and psychological barriers to posture improvement.

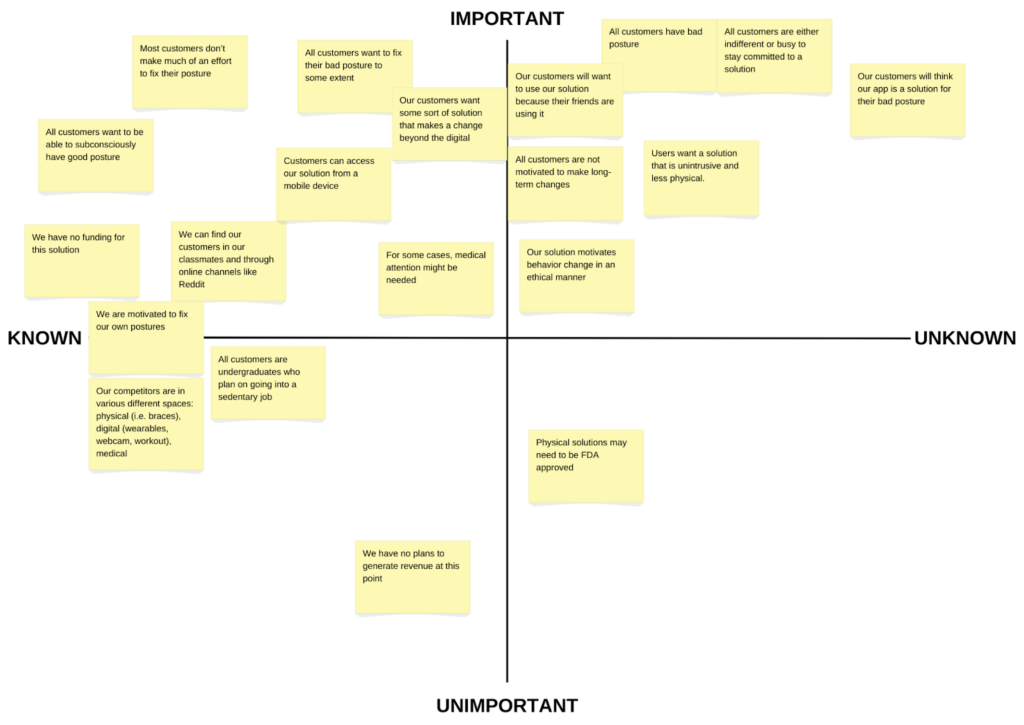

Intervention Design

In this section, we took our insights from our baseline study and started testing our theories and assumptions as well as the basic principles of our app. We began with some assumption maps to understand what were our general conceptions of posture habits for our audience and then tested our most important ones, which we discuss in-depth in this next section.

Assumption Maps & Test

From our assumption map (linked here), we gained insights into how people perceive their posture habits and how they might want to adjust them. We observed various assumptions about motivations, and technical logistics—factors that shape whether or not a posture‐improvement solution will integrate into users’ daily routines.

As we refined these assumptions, some were moved into the “important and unknown” quadrant, giving us a more concrete basis for testing.

Here are some key insights drawn from working on our assumption map:

- One of the most clear takeaways from our analysis is that people may not want to wear bulky or invasive devices which may communicate a low tolerance for physical inconvenience.

- It is also important that we keep at the forefront, solutions they can integrate into existing routines without adding too much friction(and risking user motivation dropping off at record speed).

- For posture, which is an inherently personal behavior, peer and social influence could be a potentially strong ally if it’s framed in the right way.

- Even when people say they want better posture, they may often lack the persistence to do what will create change.

- We may need to leverage some habit formation strategies to keep the staying power of our future intervention.

Below are the three assumptions we chose to test (using the test card as guidance), presented below:

Assumptions We Chose To Test and Experiment On

Assumption Test #1:

Hypothesis: We believe that the users want a solution that is unintrusive and less physical.

Test: To verify that, we will show them the four solutions that are physical and intrusive, digital and intrusive, physical and unintrusive, and digital and unintrusive.

Metric: And measure whether or not, on average, digital consistently ranks above physical and whether or not, on average, unintrusive constantly ranks above intrusive. We will specifically be using the average.

Criteria: We are right if digital and unintrusive solutions have a higher mean than physical and intrusive solutions.

Assumption Test #2:

Hypothesis: We believe that customers will want to use our solution because their friends are using it.

Test: To verify that, we will share two fake equally effective products, where we tell them that it was referred by 5 of their friends or that they found it themselves. Have them rank how willing they are on a scale of 1-5 to sign up for the app.

Metric: And measure which one has a higher average ranking.

Criteria: We are right if the one with information on friends gets a higher ranking.

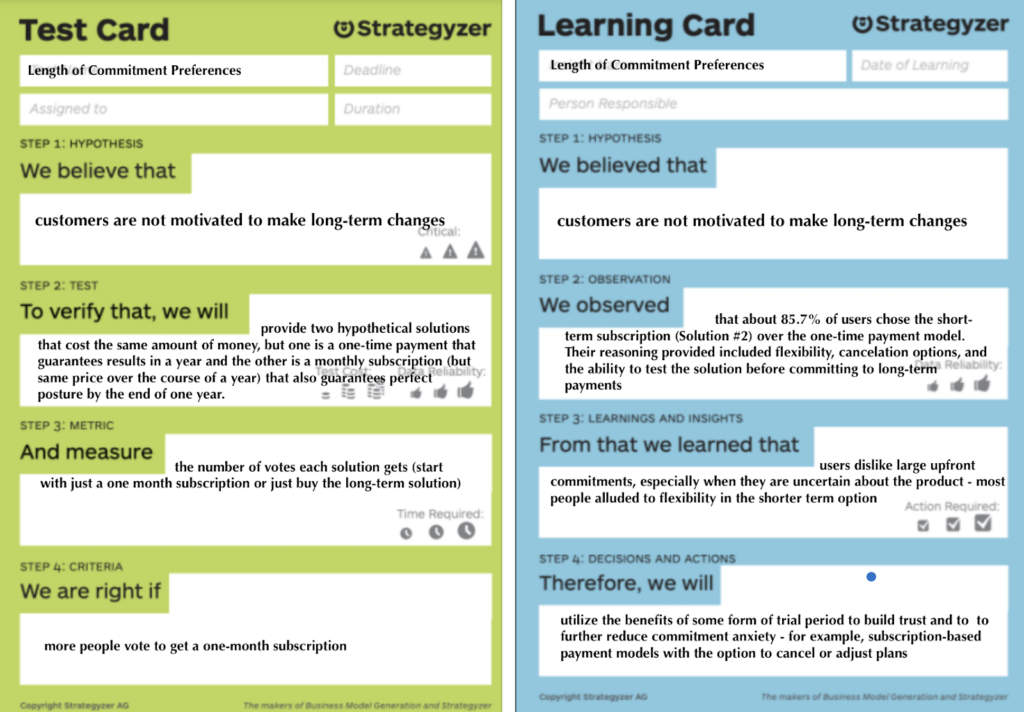

Assumption Test #3:

Hypothesis: We believe that customers are not motivated to make long-term changes.

Test: To verify that, we will provide two hypothetical solutions that cost the same amount of money, but one is a one-time payment that guarantees results in a year and the other is a monthly subscription (but same price over the course of a year) that also guarantees perfect posture by the end of one year.

Metric: And measure the number of votes each solution gets (start with just a one month subscription or just buy the long-term solution).

Criteria: We are right if more people vote to get a one-month subscription.

Detailed Experiment Design

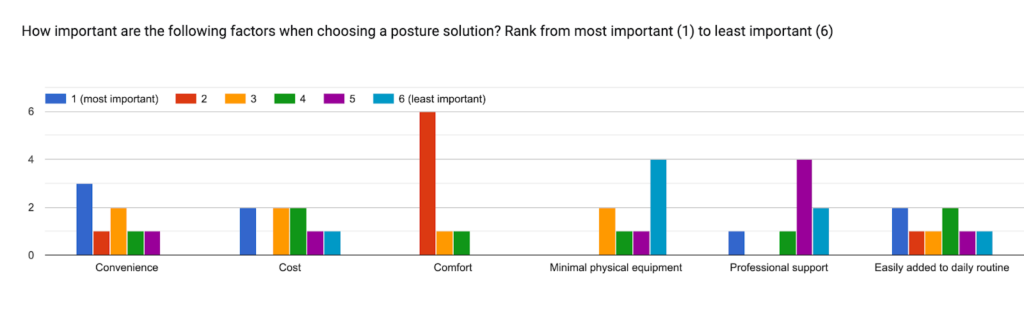

Assumption Test #1:

Present interviewee with a Google Form of the following to-be-ranked products:

- Tracking app

- Wearable reminder that buzzes every minute

- Ultra thin back brace

- Chiropractic visits (in person)

Statements should be ranked on a scale from 1-4 based on posture improvement solutions that they would most prefer, with 1 being most likely, and 4 being least likely.

Interviewee proceeds to describe, in words, why they picked their top option.

Finally, interviewee ranks 6 factors of what matters most to them for a solution from the following:

- Convenience

- Cost

- Comfort

- Minimal physical equipment

- Professional support

- Easily added to daily routine

Interviewee ranks them from 1 (being the most important factor) to 6 (being the least important factor).

Based on our research, there are four domains of solutions: physical and intrusive, physical and unintrusive, digital and intrusive, and digital and unintrusive. We chose a solution for each category with the following matches:

- Tracking app – digital and unintrusive

- Wearable reminder that buzzes every minute – digital and intrusive

- Ultra thin back brace – physical and unintrusive

- Chiropractic visits (in person) – physical and intrusive

As a result, the first question aims to investigate which category of solution is most preferred by customers. If the average ranking of the digital and unintrusive solution is higher (and preferably the highest) compared to a physical and intrusive solution, we will know our assumption is correct.

Additionally, the questions asking about why an option is their favorite pick will help us glean further insights as to why they picked a particular solution. This was specifically done in order to determine if they mention the digital/physical or intrusive/unintrusive scales. If they do, we can weigh these answers more heavily and be confident in our assessment of which type of product is most preferred.

Finally, the questions asking the participant for a ranking of important factors for a solution, allows us to understand what is most important in a solution for the participant. By analyzing which factors are most highly rated on average, we are able to determine which factors matter most to participants. If they highlight a factor like “convenience” or “minimal physical equipment”, it will help us better understand where the solutions fall along the axes.

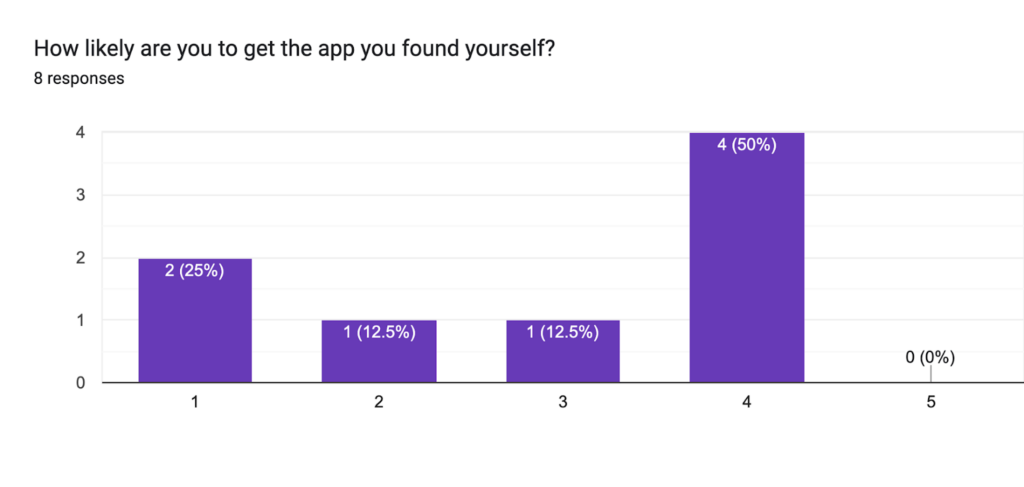

Assumption Test #2:

Present interviewee with a Google Form with the following proposed scenario:

Let’s say you have found two apps to fix your posture! The first one is an app that was recommended to you by 5 of your friends who are using it and the other app was one that you found on your own, but seems like it would be effective from the research you did.

Have the interviewee rank each solution based on how likely they are to get the app, with 1 being very unlikely and 5 being very likely.

Pose the interviewee with a follow up question asking them whether they prefer an app they found themselves or recommended by friends for a health and wellness app, or if they have no particular preference.

Third, ask the interviewee the following question:

Imagine you’re deciding between two posture improvement products that are equally effective. Which of the following would most likely influence your choice (choose up to 2)?

The options they can select from should be as follows:

- Personal research and reviews

- Friends or family using the product

- Expert/professional advice

- Brand reputation

- Price difference

- I’d choose randomly if all other factors are equal

The first question was chosen to understand what type of posture related app our audience would prefer and if they would be more likely to use an app that their friends are using to test our assumption. If there is a higher average rating for the app recommended by friends, we will know our assumption was right. The second question, similarly, asks people if they have a direct preference in case our last question didn’t make it clear enough. If more people have a clear preference for an app recommended by friends, we will know our assumption is correct.

The final question aims to understand what factors most influence an individual’s decision to choose a particular product. This question was chosen because our underlying assumption was made to best understand how to drive customers to use a product. As a result, if we understand other similar factors, we can incorporate those into our solution. The factors with the most votes are indicative of the factors that users most care about in their solution and we want to make note of and make sure to implement them in our final product.

Assumption Test #3:

Present the interviewee with a Google Form of the following proposed scenario:

Let’s say you have found two products that are both equally effective and can fix your posture permanently in one year. The first one costs $144 up-front for the whole solution. The second one is based on a monthly subscription, and costs $12 per month (meaning by the end of the year, you will have paid $144 for that product as well).

Have the interviewee select the solution that they would prefer and briefly explain what led them to that preference.

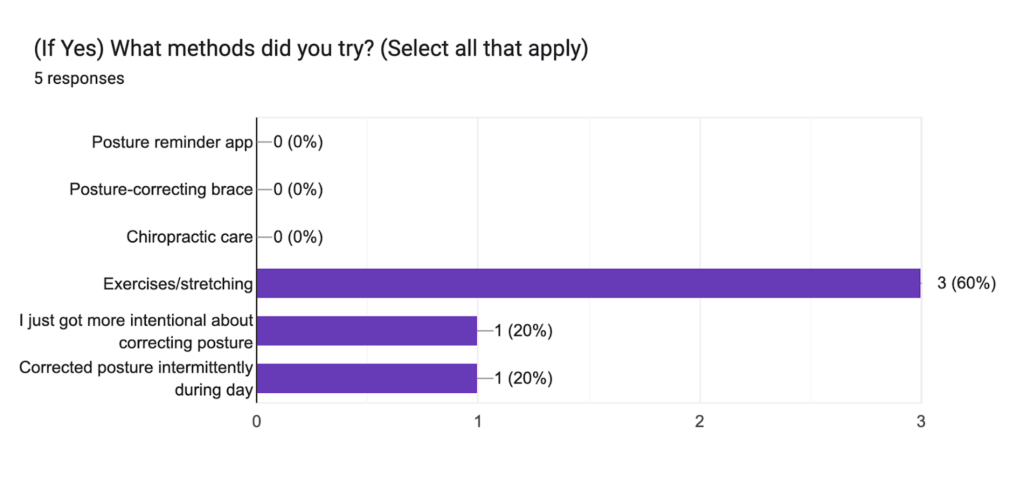

Follow up by asking the interviewee if they have ever tried to improve their posture, and if yes, have them select which methods they have tried.

Lastly, ask the interviewee how long they consistently maintained the habit, with the options less than 1 month, 1-3 months, 3-6 months, 6 months-1 year, and over 1 year.

The first question was chosen to understand whether the interviewee would prefer a solution that requires a year-long commitment (due to the up-front cost of $144), or a solution that allows them to pay monthly and the ability to walk away ($12 each month, adds to the same $144 yearly). Additionally, it tries to understand better why the interviewee preferred the solution they selected. If more people prefer the monthly subscription solution because they want the option to save money and cancel the subscription, we know our assumption is correct. The second and third questions were asked to see if people have tried to fix their posture before and how long they were able to maintain that commitment. If the majority of people who tried to fix their posture only sustained the habit for a few months or less, we know our assumption is correct. Looking at the responses to the methods that people have tried in the past, we can better design our solution to address problems with past tried solutions.

Recruitment Process

Our project focuses on the bad habit of bad posture. From our needfinding interviews, we realized that most undergraduate students spend a lot of time sitting down and in front of their devices. In addition, these students are busy and are constantly in the presence of other people. Based on our assumptions, it made sense for us to recruit people who know a lot of people/are pretty social, and have packed schedules (i.e. do research, go to the gym, go to club meetings, etc. in addition to class). Busy students should have a harder time keeping themselves in check with their posture, therefore being unable to commit to any long-term solutions and social students might be more easily influenced by their friends’ opinions. In addition, both student groups should want a solution for their bad posture that would not arouse any sort of attention, yet help them mindlessly.

Experiment

Experiment Link: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSclr0Vtys21RCHEIlHeEcP2wXhgCxgMpOkafi8xerkBGkc5XA/viewform

Experiment Data Link:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ROFhIu-v17c6f7BvAXJ2KrrNFZzi00YzW9EOGHMmP04/edit?usp=sharing

How These Results Build on Our Previous Work

In earlier stages, we identified recurring themes around user convenience, social influence, and difficulty with sustaining posture improvement efforts. Our assumption map helped us focus on these key points. The following learning cards show how each experiment’s outcome either confirmed or refuted these assumptions.

Synthesis

Learning Card #1:

Hypothesis: We believe that the users want a solution that is unintrusive and less physical.

Observation: We observed that the ranking data from the responses shows that the digital solution (e.g., tracking app) and unintrusive solutions (minimal disruptions to daily routine) consistently scored high. The tracking app was the most preferred option (on average) for 3 out of 7 respondents. Several users emphasized non-invasiveness and seamless integration into daily life as key reasons for their preference.

Learning and Insights: From that, we learned that users are highly influenced by solutions that do not disrupt their day and are easy to implement (unintrusive). However, some physical options like the back brace still had reasonable support due to perceived effectiveness.

Opportunities for Intervention: Since users prioritize minimal disruptions, any future product design should be built around seamless integration. For example, a smartphone app that works passively in the background could reinforce posture checks without adding an extra physical device. This aligns with our goal of remaining as unobtrusive as possible.

Decisions and Actions: Therefore, we will prioritize designing a digital product with minimal user intervention while also exploring lightweight physical options.

Learning Card #2:

Hypothesis: We believe that customers will want to use our solution because their friends are using it.

Observation: We observed the average likelihood rating for adopting a friend-recommended app was 3.43, while for the self-discovered app, it was 3.0. In addition, the majority of participants (4/7) stated that they prefer products that many people they know are already using (compared to products that they found themselves or having no preference). In terms of selecting which factors would be most likely to influence their product choices, Personal research and reviews, Friends or family using the product, and Expert/professional advice were all ranked equally high (4 votes each).

Learning and Insights: From that we learned that while friend recommendations received a higher rating compared to self discovery, personal research and expert opinions were equally influential, which suggests that users do not rely solely on their social circles for decision-making. Our results show that the popularity of a product among user’s social groups does matter a moderate amount (14.3% higher likelihood), but there might be other factors that are equally as powerful in terms of influencing a user to adopt a product.

Opportunities for Intervention: By embedding social features—such as group challenges, friend leaderboards, or easy ways to share posture progress—we can leverage peer influence while still respecting that users also value professional/expert endorsements. Incorporating reliable research or expert validation alongside social sharing could further encourage adoption

Decisions and Actions: Therefore, we will still create a product that encourages social sharing since peer recommendations are still very influential. However, we will also make sure that our product can appeal to users who do their own research and try to get professional/expert endorsements.

Learning Card #3:

Hypothesis: We believe that customers are not motivated to make long-term changes.

Observation: We observed that 6 of 7 participants preferred the monthly subscription-based solution over the up-front yearly subscription, and gave reasons such as having the option to cancel and spending less money monthly. Additionally, 5 of 7 respondents mentioned that they had tried to fix their posture in the past and selected methods such as stretching and being more intentional about their posture. Lastly, of those 5 participants, only 1 of them recorded that they had maintained their habit for longer than a year, with 3 of the others failing to maintain the habit for more than 6 months.

Learning and Insights: From that, we learned that users prefer a solution that will give them the option to easily walk away and not make a long-term commitment to solving their posture problem. We also learned that 5 of the 7 individuals have tried to fix their posture in the past, meaning that despite their reluctance to engage in long-term solutions, most participants (5 out of 7) express a desire to improve their posture.

Opportunities for Intervention: A flexible subscription model or “freemium” approach could help users try the solution without committing for a full year upfront. This lowers barriers for long-term adoption, acknowledging that many users have tried posture fixes but did not maintain them beyond a few months. Gradually building trust and demonstrating effectiveness may help transition them to a more sustained plan.

Through our assumption testing, we validated that intrusiveness, social influence, and long-term commitment are pivotal factors shaping the adoption of posture-improvement solutions. By focusing on a minimally invasive, socially supported, and flexible model, we plan to prototype a digital intervention that addresses these needs. In the next phase of our study, we used these assumptions to implement an intervention.

Decisions and Actions: Therefore, we will create a product that may use a subscription-based model with flexible cancelation options and also offer a trial period to build trust before longer commitments.

Storyboards

Storyboard #1

Description

This intervention design introduces a social component to helping you fix your posture! Essentially, the idea is that you and your group of friends will all sign up for an app and use a currently available tracker which essentially sits on either your back or neck. It keeps track of your posture by vibrating whenever you slouch, reminding you to fix your posture, and it also keeps track of the percentage of the day that you spent slouching as opposed to the amount of time that you had good posture. Our app is a companion for this device by allowing you to set benchmarks and use group accountability to improve your posture. There are periods of time (which vary to introduce reward unpredictability) in which your group must hit a certain benchmark of improvement. If you do, then you’re provided with coupons or discounts to visit a restaurant and dine with your friends (which in an ideal world would be a partnership with restaurants in exchange for sending customers their way). If even just one person in the group doesn’t meet their goals, the entire group is ineligible for the reward in this period. This way we hope to introduce social accountability to improve their posture (and the social component seems to matter a lot for posture), reward their personal improvement with individual goals, and track their progress with an impartial device that can’t be rigged to always give them the reward.

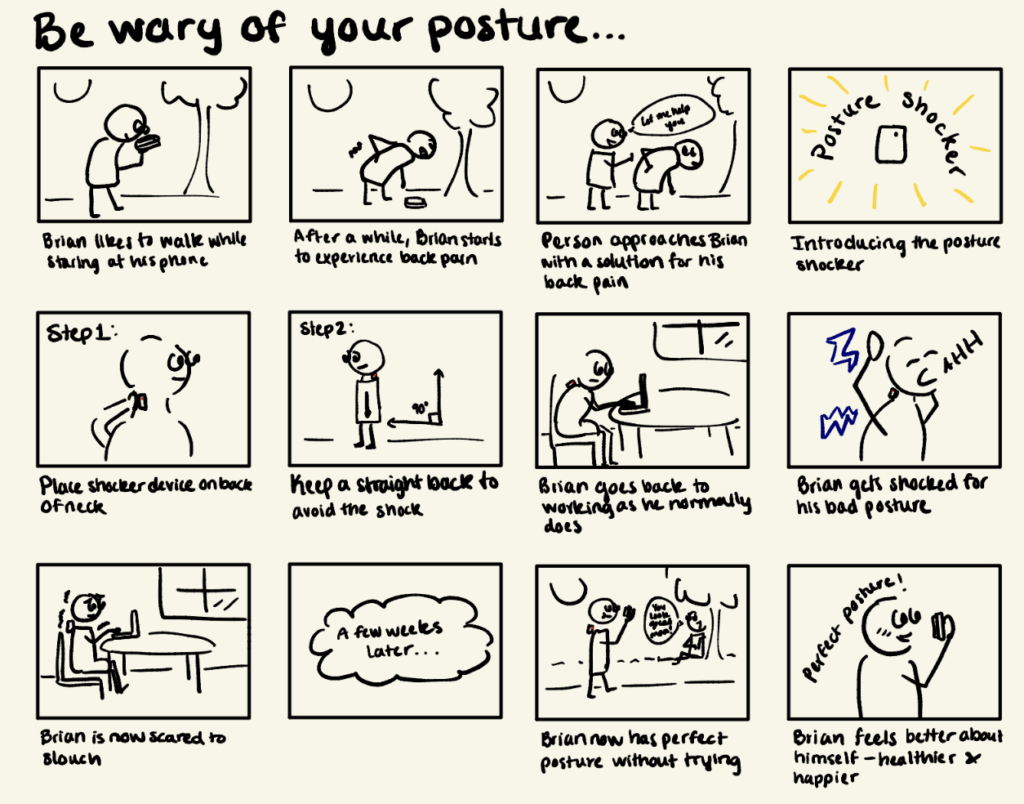

Storyboard #2

Description

This is an extreme version of the solution before this, but with no social component. Essentially, this is for individuals who are very motivated to improve their posture but don’t want to spend too much time thinking about it or wasting energy on it. As a result, the device functions on its own without much of a tracking component (it exists passively, only if the individual wants to check it but it’s by no means required). Any time that the tracker realizes that the individual is slouching, it will shock the person (not painfully, just strongly enough that they can’t ignore it). The vibration also persists until the posture is corrected. Although they will struggle with the muscle pain at first, we believe that with consistent repeated practice, they will be able to build their muscles more than if they were to just straighten their backs once a day for a few minutes. This is a more passive form with external reminders forcing you to correct your posture, since we found with our interviewees that people will not actually care about gentle reminders as the day goes on with no other reinforcement and they will be too busy to spend additional time thinking about the solution.

Storyboard #3

Description

This is another social solution, where a group of friends can sign up together to keep each other accountable. It takes more of a gamified approach, where the idea is that if you see your friend slouching in public, you take a photo of them and can upload it to the app. The app has a leaderboard that will add points based on the photos that you’ve taken of your friends as well as subtract points for when you’re caught slouching. Our interviewees primarily mentioned that they’re most likely to care about their posture in social situations and we also noticed that people are most likely to fix their postures when they see photos of themselves slouching. This intervention takes components of both of these insights to make a more fun, gamified approach. Our hope is that when participants see these photos of themselves, they will be motivated to fix their posture long-term and not get caught in these photos, as well as will want to catch their friends with these poor postures (social component) to increase their points.

Best Storyboard: Storyboard #1

Overall, we thought that the best idea amongst our storyboards came from storyboard #1. The reason for this is that we thought the second two ideas were a bit too focused on being punitive or critical. For the second storyboard, shocking an individual can be quite startling and harmful and is likely not the best approach to help them improve their habits. Similarly, for the third storyboard, as a team, we thought this wouldn’t lead friends to support each other on their journey of posture improvement and would also create a negative association for them with posture since if they get caught slouching, their friends make fun of them. We don’t want fear to be our motivating factor, as this might just lead people to not use the app. As a result, we chose storyboard #1 as it allows there to be social influence, but in a positive manner, since everyone doing good benefits the whole team (as opposed to teammates waiting for each other to fail). Specifically for our users, they already have a negative connotation towards posture and have low motivation to fix it. We don’t want to make this worse by providing an app that only punishes them more for bad posture. We need to instead support, motivate, and reward the users, which is what the first storyboard reinforces.

Intervention Study

Our intervention study was moderately successful as it provided valuable insights into how group observation and accountability influence posture awareness and improvement. The participants of the study actively engaged in monitoring other peers’ posture, and the process encouraged self-awareness. Many participants expressed they were more mindful of their own posture when they were actively observing someone else’s, suggesting that social accountability might not only raise awareness but also trigger self-regulation.

However, while this study demonstrated that social factors influence posture habits, we noticed that challenges arose in tracking consistency and effectiveness. Some participants found it hard to track in 15-minute increments, and a lack of real time feedback made change difficult to consistently incorporate.

What we learned

Below are some of the key insights that we learned through this intervention study:

- Social Influence Matters – Participants seemed to adjust their own posture when reminded to check someone else’s, showing that the act of observing someone else actually serves as a posture intervention.

- Consistently Tracking is Difficult – Some participants/observers noted that tracking an individual in 15-minute intervals or 15 minute periods throughout the day was difficult and that a more automated or structured approach is needed.

- Real-time Feedback is Needed – Posture ratings were logged some time after the observations occurred, which proved to be less effective than a wearable device that buzzes, prompting good posture immediately.

- Awareness of Being Tracked Changes Behavior – After participants were told that their posture was being tracked and compared to their friends, many of them adjusted their posture more frequently, especially when they were around their fellow posture group members. This suggests that social competition and awareness of comparison can be effective motivators for improving posture.

Our Process

Study Setup: Participants were recruited in groups of 2-3 and assigned to observe a peer in their group’s posture for a total of one hour a day, logging posture ratings at 15-minute intervals throughout the day. Specifically, we had one group of two and one group of 3 for a total of 5 participants. The study was conducted over four consecutive days. Participants were asked to rate their friends’ posture from the following options: Strongly Upright, Moderately Upright, Neutral, Moderately Slouched, or Strongly Slouched. Each participant was also aware that their posture was being tracked and compared to their friends about halfway through the study.

Recruitment: The study included university students who engaged in daily activities involving varied postures, such as studying, socializing, exercising, eating, etc. We specifically chose groups of friends that would consistently see each other at least 4 times during a 4 day period. All of our participants had not previously participated in any of our studies, so they had no prior knowledge about our project.

Key Research Questions:

- Does social accountability improve posture habits?

- Do participants become more aware of their posture while observing others?

- Will participants change their posture behavior after being aware that they are being tracked and compared to their friends?

Key insights from the intervention study

- Peer observation alone does not greatly influence habit change – The format of peer observation raised awareness of individual posture, but without real-time feedback, many participants did not adjust their posture.

- Social Accountability is Powerful – Many participants noted that their posture was improved just by knowing that they were being observed at some point. Additionally, many noted that checking a friend’s posture helped them be more aware of their own posture.

- Comparison and Awareness Drives Action – After participants were explicitly told that their posture was being tracked and compared to their friends’ postures, they were more likely to adjust their posture when in group settings. This indicates that awareness of social comparison can be a strong motivator for behavior change.

Opportunities for Intervention

Based on our intervention study, our solution – an application that utilizes social accountability through a wearable posture tracker and group scores – needs to emphasize the following:

- Real-Time Posture Feedback – Instead of manual logging, the wearable needs to provide instant feedback through notifications or buzz alerts when poor posture is detected

- Gamification with Progressive Goals – Instead of just penalizing bad posture, our application should include rewards and incentives to make the experience more engaging, desirable, and sustainable.

- Enhanced Group Interaction – Since social accountability proved to be so effective, the app should allow users to nudge and encourage their friends, provide positive reinforcement, and show metrics that track group performance toward goals and rewards.

- Comparison Features to Encourage Better Posture – Since awareness of tracking and peer comparison increased posture improvements, the app could incorporate elements such as leaderboards, shared progress updates (including being able to see other group members doing well), and recognition of users that achieve a goal to further encourage better posture habits.

Our intervention study highlights key factors that influence posture awareness and behavior change, emphasizing the importance of real-time feedback, social accountability, and structured tracking. These insights will shape the way we refine our solution and ensure that it aligns with the behavioral patterns we observed in participants.

To translate these findings into a user experience, we can explore system paths. Our system paths will outline how different personas interact with the app, particularly how individuals like Valeria, a proactive user, would discover, onboard, and integrate her friends into the experience. In the following section, we detail the main user flows that define our solution based on insights from our intervention study, showing how our app facilitates posture improvement through social dynamics and gamification.

System Paths

Process

We began by considering our different personas and the exact steps of how they might be introduced to the app. We decided that one persona, Valeria, would be the one who is most likely to discover the app and get her friends to join her. From here, we went through all the stages that she would be involved in, including onboarding, creating a group and inviting friends, and using the app with rewards. From there, we considered where the other group members would join in (particularly at what stage) and what parts of the process they would skip (such as inviting other friends). This led us to create an overall pipeline for all the personas and we were able to highlight the main cycle in the app that doesn’t include the onboarding.

Persona Path Divergence

Valeria is the first to discover the app and sets the process in motion by researching its features before inviting others. She is detail-oriented and wants to be fully informed about posture tracking and rewards, so she does not skip any initial onboarding steps. However, once she has created her group and shared the app with friends, she may bypass further screens that no longer feel relevant.

Jacob relies primarily on social proof and his friends’ enthusiasm to adopt new apps, so he will join after Valeria convinces him it’s worthwhile. Because he’s more competitive than inquisitive, he may skip certain explanatory screens in the onboarding if the group is already actively challenging one another. Jacob’s path deviates from Valeria’s because his main focus is social engagement and competition, leading him to prioritize jumping straight into challenges rather than reading detailed instructions. This behavior highlights how personality traits—like his competitive drive—translate into different user flows.

Cheban, on the other hand, is somewhat indifferent until there’s a compelling social or monetary incentive. He joins the app only after hearing from friends—like Jacob—about potential rewards, which leads him to bypass any deeper educational materials about posture benefits. His path diverges because his motivation is tied to immediate payoff and inclusivity; if he doesn’t sense an immediate reward or sees others gaining benefits, he’s less likely to engage or retain steps in the flow.

Why a System Path

The system path helped us spot gaps in our understanding (e.g., where social accountability or professional recommendations come into play) and served as a foundation for designing our intervention study.

Insights from the System Path

We paid special attention to potential social interactions, points of friction (e.g., cost or inconvenience), and triggers for re-engagement.

- Social Influence: Jacob relies heavily on friends’ recommendations, while Valeria is more research-driven. Cheban cares about social proof(does not care otherwise, until he feels left out) but also needs convenience due to his busy schedule.

- Reusability of Features: Many steps, such as “download an app” or “get real-time posture reminders,” appear across all personas, suggesting we can design features that benefit everyone but still allow for personalization.

- Motivation: All our personas show a tendency to drop off if the solution is too intrusive or if they don’t see quick benefits.

- Opportunities for Social Accountability: Our path highlighted that social or group-based strategies might keep certain users (like Jacob and Cheban) engaged longer even without enough intrinsic motivation.

Opportunities for Intervention

Different personas respond to different motivators (social pressure, professional advice, convenience). Given these insights from our system path, we designed an Intervention Study to test whether group accountability and social rewards can motivate users to improve their posture over a short period. We focused on group dynamics because the system path revealed that social influence was a recurring theme for multiple personas. We also integrated the idea of quick feedback (e.g., observation scoring) because our system path showed that users need immediate reinforcement to stay engaged.

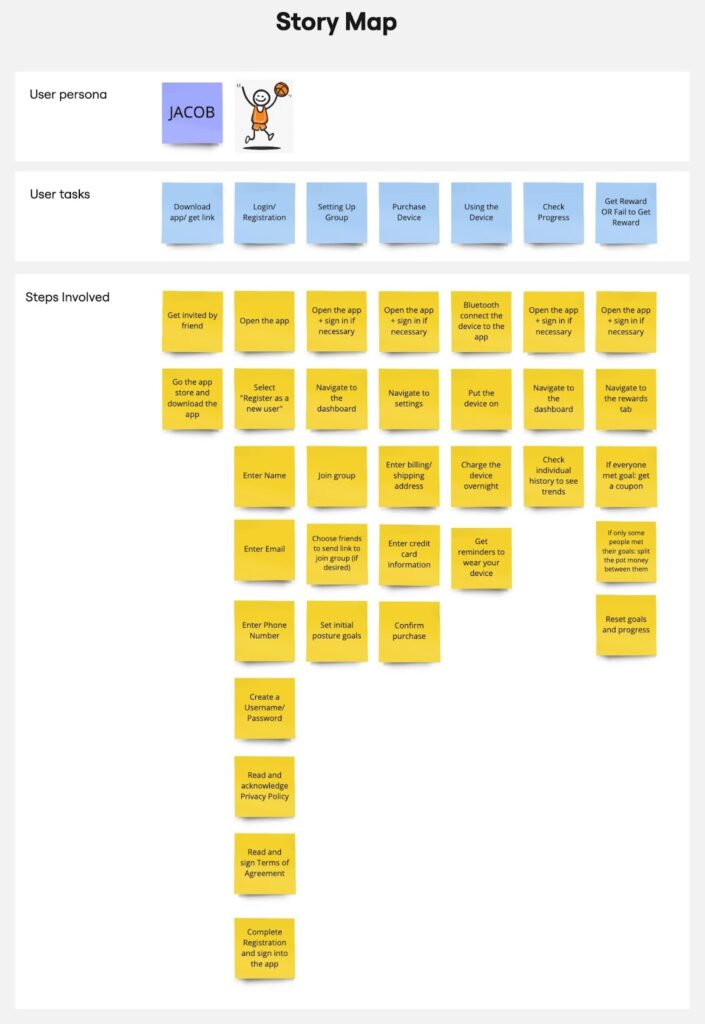

From the system path, we’re able to see a general flow of how our app works and how different personas are involved. However, we want to really zoom in on an individual persona and break down these tasks as much as we can to understand the process in depth. Let’s take a look at a story map for our persona for Jacob.

Story Map

Here is our story map for our user persona, Jacob (for more information on Jacob, you can see our baseline study above)! We thought Jacob’s use case and story map for our app was pretty similar to what other users would experience, so we only have one story map.

Process

In order to create this story map, we wanted to first identify the user persona that we wanted to walk through this app with. We chose Jacob, who is our student-athlete persona that gets invited to join the app/group and also invites his friends (for a refresher on the persona, you can check here). Next, we wanted to identify the user tasks, which were essentially all the ways that our user might want to interact with our app in their journey to improving their posture. We started from how they might encounter the app or what led them to download it, and included all following tasks, such as signing up for the app, obtaining and using the device, and checking their progress and getting rewards. Once we had identified the key things that a user would be doing on our app, we wanted to identify the steps for each one in detail to best understand exactly what each task entails. As a result, the third section of our story map describes the exact steps, primarily in order, that each task would consist of (subtasks that are as small as possible but still stand on their own).

Why a Story Map

When thinking about a solution, sometimes we can get really caught up in how we think it will work. It’s really important to consider how the app functions from the perspective of a user to see if anything is burdensome, unclear, or poorly planned. In this situation, using a story map helps us see exactly how and in all ways we currently expect users to engage with our solution. This has made it clear exactly how a user might approach our app, including their pain points, any points of friction, and potential gaps between our perception of the app and their perception of the app.

Key Insights

From our story map, we were able to see that many of the tasks are related to onboarding and it is a rather involved process. Considering it is hardest to get a user to stay on an app when they first download it, this may become an issue for user retention. Even within the onboarding process, the specific step of purchasing and using a device, which makes up its own individual tasks, shows another potential point of friction for the users. Considering that they have to invest in it before even really trying out the app and that they have to constantly remember to do things like connect, charge, and wear it might end up being an issue for users.

Additionally, this story map shows how important the social component of our app really is. So many different tasks tie into a friend group using it – from getting invited by your friends to getting rewards based on how the entire group performs.

From this story map, it also becomes apparent that some of our tasks need further clarification. For example, in order to split up the pot between individuals who did well, we need to keep track of individual progress as well. The reward system is set up in a way to overall prioritize group winnings, but we need to further flesh out the scenarios in which no one does well or only some group members do well.

Finally, we also noticed how in the “check progress” task, people may not always know exactly how the point system works to understand their progress, so it’s important that we clarify and have a really straightforward point system to support the users.

Opportunities for Intervention

The story map brings up key points that we need to consider in our intervention. For one, as mentioned above, our onboarding process seems rather burdensome, so it would likely be a good idea to discuss how we can reduce the amount of work and time involved in just setting up the app so we make sure users don’t fall off the app mid-onboarding. Second of all, we also want to consider reducing the burden of the device on the user. We chose a third-party device after a lot of discussion as it made the most sense for our users and was the best tracker we could find. However, this may lead to other issues that cause concern for the user. In our intervention, we need to better consider challenges that the device might introduce and how to deal with these (especially since a lot of these will likely be part of the onboarding process, making it even more difficult).

Third, we seem to have a gap in terms of understanding and tracking individual progress. In our intervention, instead of making it a small point that doesn’t seem as involved with the team progress updates, we need to create a bigger emphasis and focus on this with a clear-cut points system so users can intuitively understand how they are doing. One potential solution is to only track individual progress and use team progress to instead give random rewards (as we’ve seen in readings that the only good variety in habit-development is variety in rewards).

How this lead to MVP features:

For our story map, we had made a list of all the steps and features that would be involved for each task. For the MVP, we then chose the most essential features for each task (since they’re all necessary) that would make the app functional for our basic goals. We reduced the amount of information necessary for onboarding, made it extra straightforward to check progress, and simplified how the goals work by standardizing them and resetting them automatically. These core set of features remove some personalization and extraneous features that would have helped us make a more in-depth app, but met our needs to establish the core functionality for the app to work.

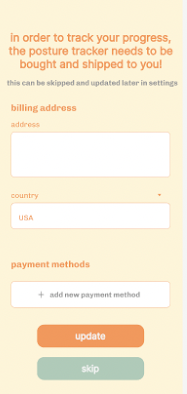

MVP Features

- Login/Registration

- Username/Password

- Invite Friends

- Create a group

- Be able to send a link to friends

- Join a group

- Purchase Device

- Billing/shipping address

- Credit card information

- Putting Device On

- Bluetooth connect the device to the app

- Charge overnight

- Check Progress

- Open the app and get to dashboard, which displays point counts

- Reward

- If everyone wins: coupon to get a meal!

- Else: people who met their goals get the pot money

For our product to be functioning, a user must have their own profile and data, which requires them to login and register for the app (the bare minimum of details to sign up is just a username and password). In order for the social component of the app to function, they must be able to make a group, invite others to a group and join a group. We chose to remove features that involve managing or modifying a group because they are not integral to the app. Another crucial part of this product is having the tracker, since that is the only thing capable of informing us about changes or improvements in the posture. For this tracker, we need specific information on how to charge them and where to send it once they have bought it and they also need to be able to connect to and use the tracker (plus charging it so they can keep using it). For the app to have any purpose, they need to be able to check their progress to see how they’re doing over time to see if they are improving at all and there needs to be the reward feature that makes the social component valuable. We aren’t incorporating the pot here at all, where people “buy-in” to compete, but there is still the social incentive that forces everyone to feel pressured to meet their goals to not hinder their friends.

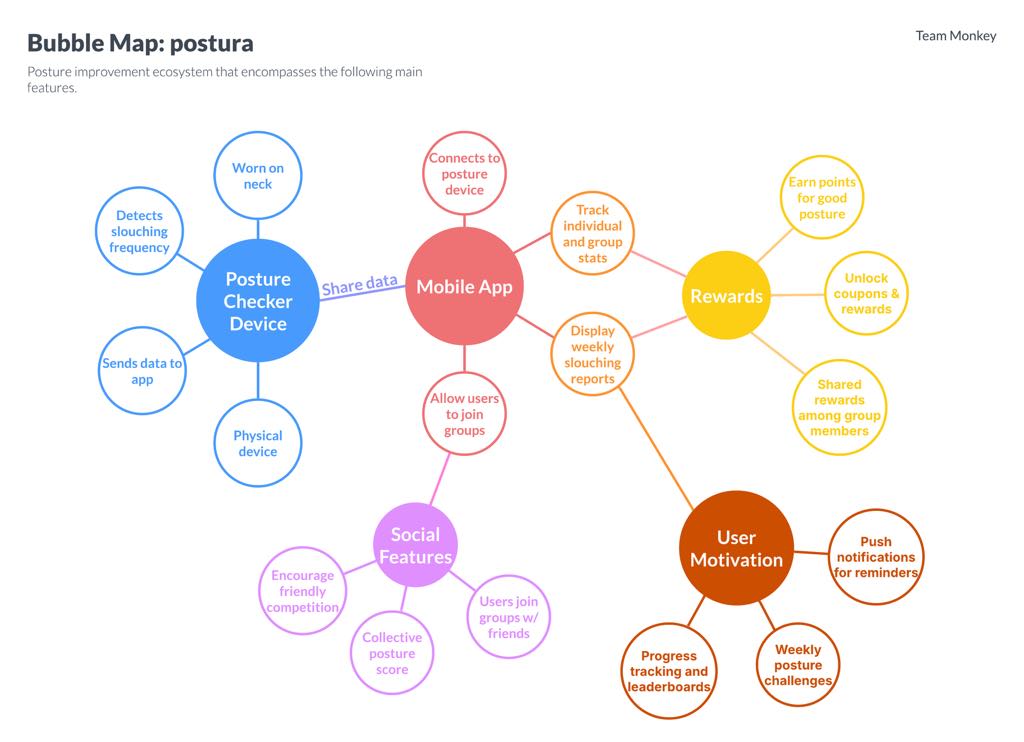

Our story maps and sketching out the features of the MVP helped us gain a key understanding of the system of our solution and what we hope to accomplish. We then wanted to understand the different pieces of our solution and how they all interact with one another to better understand the structure as opposed to just the individual needs of our solution. To address this, we created a bubble map.

Bubble Map

Model Choice and Why

After our study, we realized that we could not rely solely on a physical device to remind others or an application that relies solely on self-motivation to keep up good posture. This behavior would not be sustainable and we would not be able to make good posture a habit. We also could not avoid the application. As a result, our solution encompasses the two main components explained previously: a mobile application and a physical posture checker device.

The posture checker device on its own has some very simple functionality and purpose: have the user put it on the back of their neck throughout the day and report posture data back to the app. The device does not shock the user or indicate to them to improve their posture in order to not disrupt or disturb their everyday life. Nevertheless, this is a critical component because the application would not be able to work without this data.

On the other hand, the mobile application is what carries the majority of the functionality of this service. Using the posture checker device’s data, we can calculate a score of the week for the user. However, to make sure that the person actually cares about these statistics, we have them join with a group so they all work toward a group weekly goal – this encompasses the social feature of the app. In order for this to be even more effective in changing behavior, we introduce the concept of rewards where groups can earn certain rewards – whether it be coupons or such – that they can share and use as collective reward. In order to motivate our users, we make sure that their posture statistics are readily available and we send reminders for them to realize that they might be slouching or that they need to work harder to reach their weekly goal.

Doing this bubble map helped us realize what our service really stands for and what we can offer to our users. Our main app will rely on social components, rewards, and user motivation. Those are our core values, as was shown from the list of MVPs. In terms of how we actually made this bubble map, the solid bubbles show different components of our products, ranging from sets of features of the mobile app to the two actual manifestations (mobile app and physical device). We knew what those 5 bubbles were, and from there we brainstormed what were subsections of each as well as pieces that connected different subsections. The size is related to the importance of a bubble.. For example, the posture checker device and the mobile app are in the biggest circles because they are the two main components. User motivation is the biggest circle amongst the other factors of a mobile app because we deemed it to be the most important.

Opportunities for This Intervention

Integrating this system into workplace wellness programs can help companies encourage better posture and reduce health risks associated with prolonged sitting. Additionally, partnerships with health and fitness brands, such as ergonomic furniture companies and fitness apps, can enhance user engagement by offering complementary solutions. Expanding the social aspect through gamification, including leaderboards and team challenges, can further increase user motivation and retention.

Interaction Design

The section sums up the final stretch of our work with our project. Using everything we learned in the prior two sections, we planned out the design of our product and built a full Figma prototype! Let’s go through each step, starting with our wireflows that sum up the main user interactions that we wanted our app to have.

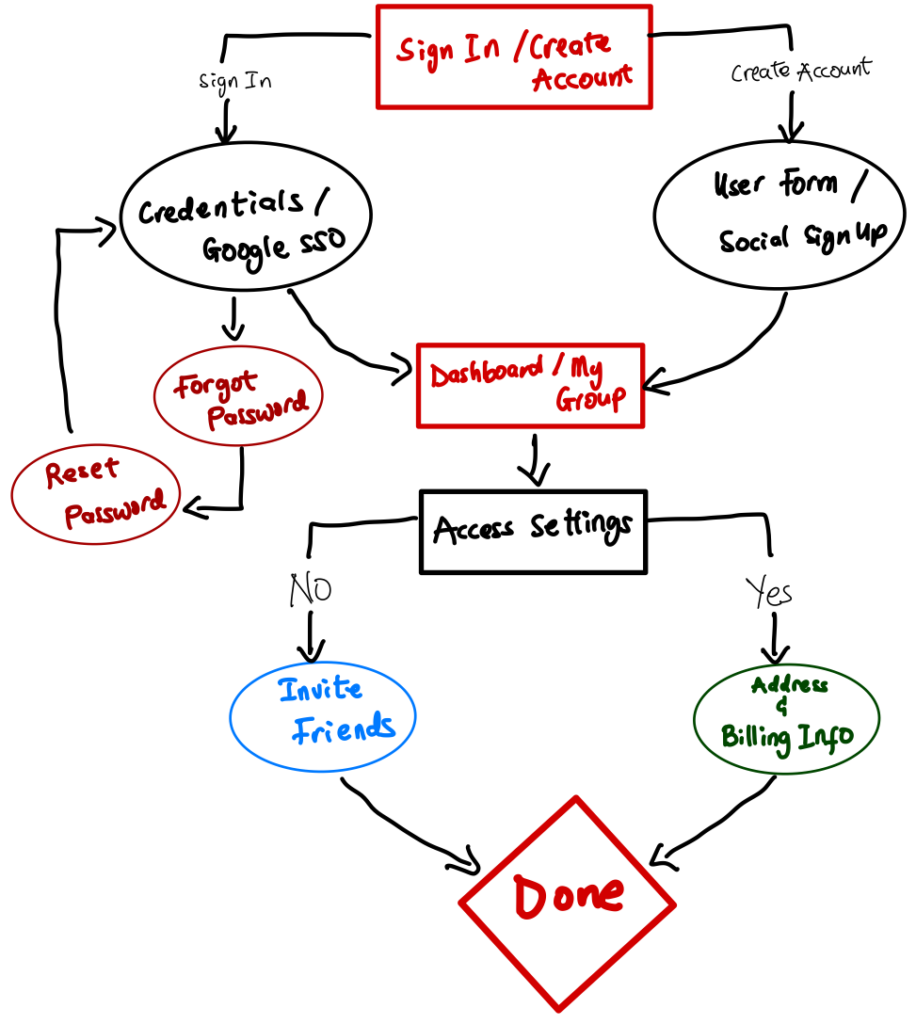

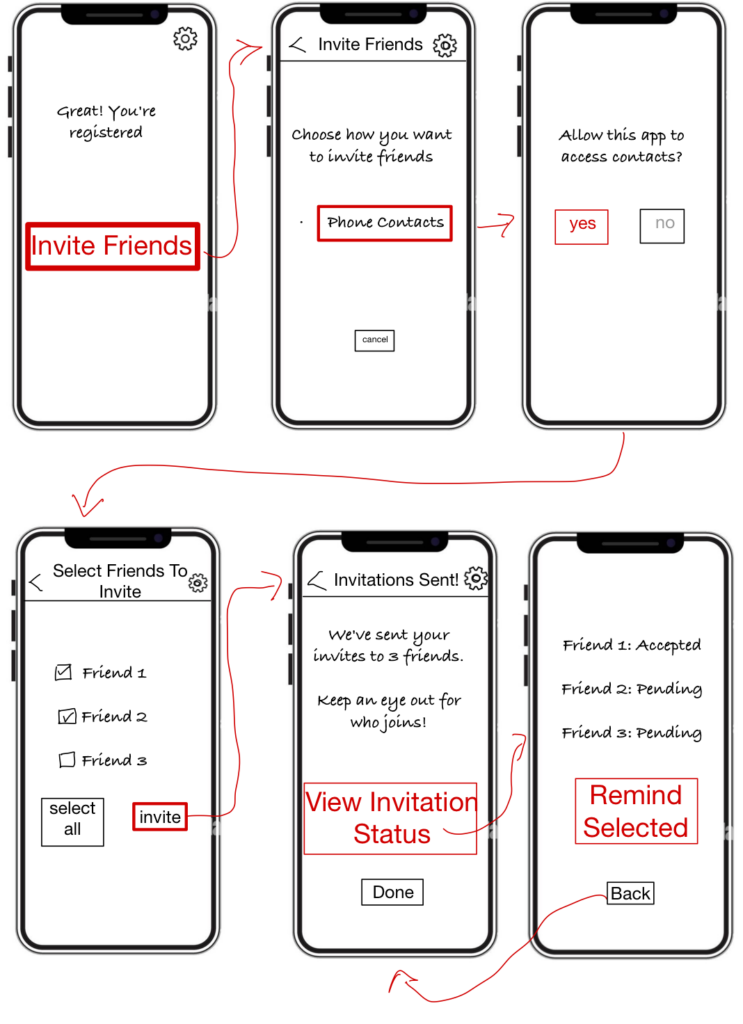

Wireflows

For our wireflows, we mapped out three primary interactions: the onboarding and sign up, inviting friends, and the overall reward system (which also involves tracking your progress over time). These three general flows encompass all of the interactions we wanted our app to have. Let’s begin by exploring the onboarding and signing up flow.

Onboarding and Sign Up

Our persona needs quick solutions that fit into their busy schedule. That’s why our onboarding process starts with the option to sign in with Google or Apple, making it easier and faster than creating a new account from scratch. We still offer the traditional username/password option, but the focus is on getting them into the app as quickly as possible.

If our persona had to go through too many introductory steps, they might give up early or delay using the app. Instead, they can start seeing relevant actions right away without distractions. This is partly why we put the address and billing info in the settings screen instead of requiring it during sign-up.

After setting up, the onboarding process encourages them to invite teammates or friends using a simple invite link, rather than manually entering contacts. This increases the chances that they’ll use the app with their friends instead of ignoring it due to hassle.

From here, let’s take a look at the invite friends flow, which, as the name suggests, allows users to invite their friends on to the app.

Invite Friends

In the original sketchy screens, users had to navigate multiple options for inviting friends (selecting contacts, adding personal messages, etc.), which created unnecessary friction.

By condensing these steps into a single “Copy Link” screen, we ensure our persona can instantly share the invite however they prefer, rather than being forced to choose from multiple pathways. Once the user returns to the My Group screen, they can decide to check the status of their invitations or move on. This ensures the interface isn’t cluttered with status screens unless the user actually wants to see them. It also gives users the right information at the right time rather than overwhelming them.

By adding a dedicated Invitation Status screen with a Remind Friends option, we reinforce social accountability—especially important for a user who wants to build momentum with friends. The simpler flow means more people are likely to complete the invite step in the first place, and the status screen encourages them to follow up.

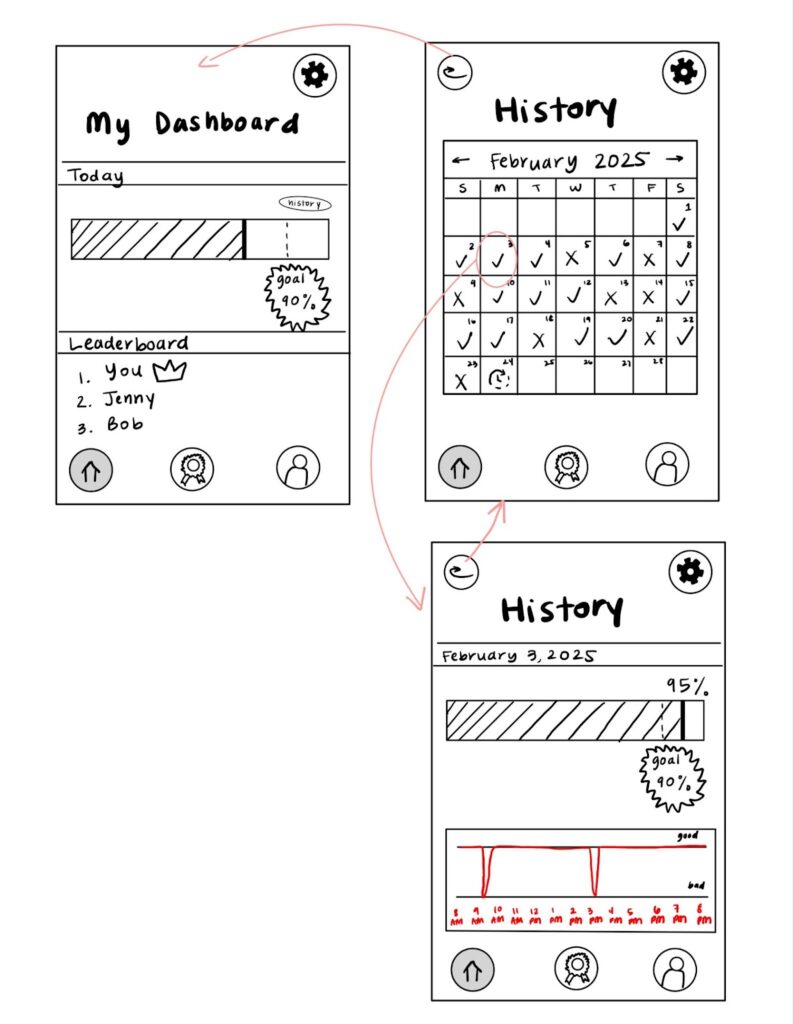

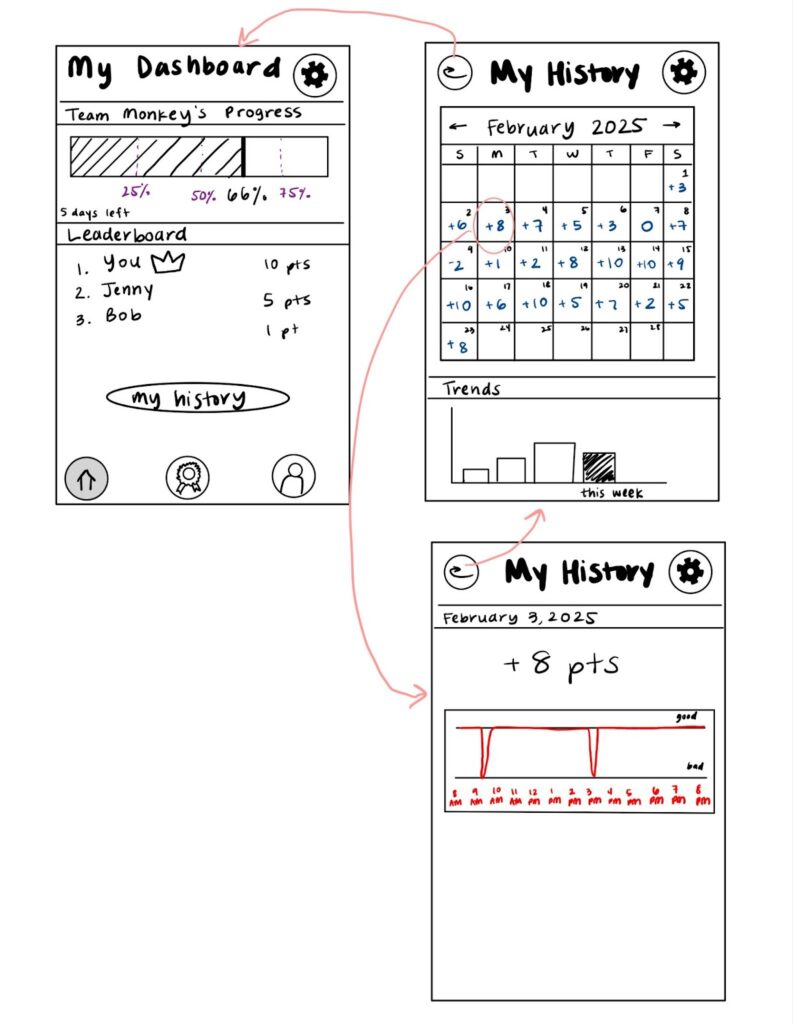

Finally, let’s explore the flow that contains the bulk of the interactions in our app: the rewards flow.

Rewards

The rewards system in our solution is designed to drive engagement and reinforce positive behavior while maintaining a streamlined and intuitive user experience. We structured the flow around key decision points and reduced unnecessary complexity to ensure users can seamlessly track their progress, view rewards, and stay motivated. We allow users to see their weekly progress, which does not cognitively overload them and gives them only the most relevant information. Additionally, the UI allows users to easily check teammates’ scores by viewing a list of their teammates and optionally clicking on them to see further details. Users can also optionally nudge teammates to remind them to keep good posture, incorporating a social accountability factor. Upon completion of a week, the system assesses whether or not the team has achieved a goal and will distribute awards if they have, or send a failure message if not.

The system automatically will reset progress after each week, making sure app maintenance is not on the users. Through this approach, our product achieves a reward system that effectively balances team motivation, engagement, and ease of use. Users are in control of their experience but are gently guided toward rewarding behaviors.

These three flows sum up how we want to guide users through all the interactions on our app. Our next step was to then make sketchy screens to illustrate how we would want to implement these flows.

Sketchy Screens

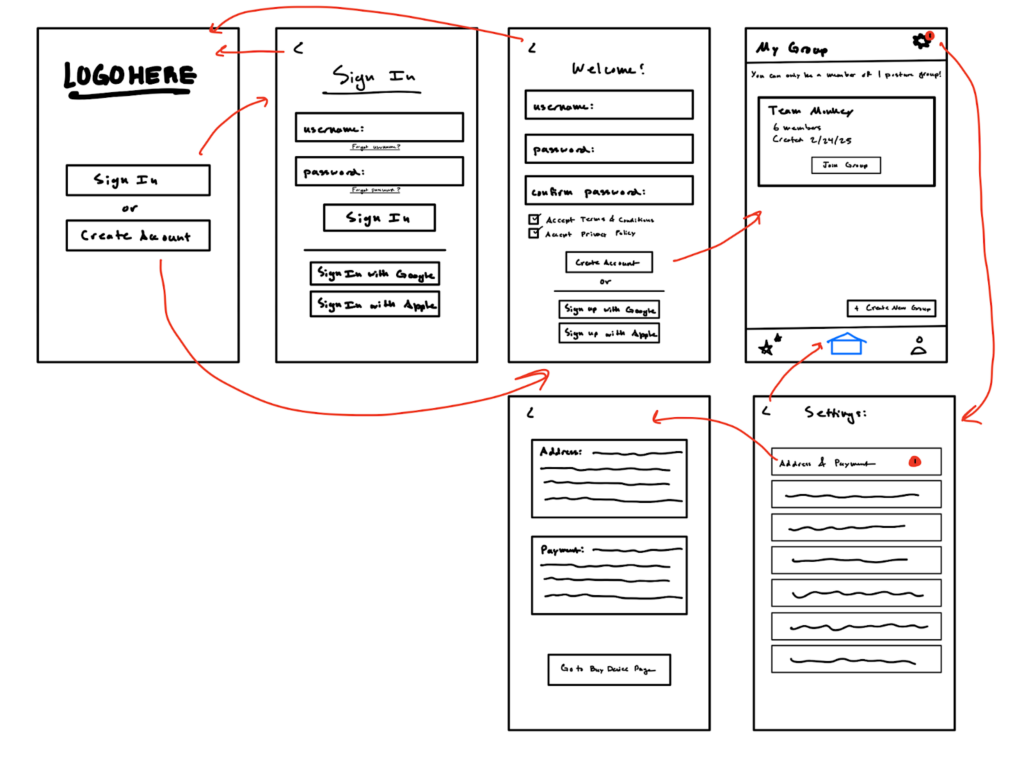

For our sketchy screens, each member of our group took on a specific screen or set of screens, so we broke apart the screens and interactions into our app into 5 parts: signing up, creating a group, inviting friends, checking progress, and rewards. Let’s begin by looking at the signing up and onboarding screens.

Signing Up

Initial

Feedback

Here is a quick summary of what the team thought:

- The UI is simple and effective, but the welcome page could be streamlined by condensing buttons

- Adding “Forgot My Password” and “Forgot My Username” options on the login screen would enhance usability

- “Sign In with Google/Apple” is a great addition for faster access

- For consistency, the home screen after first login could mirror the pre-group welcome screen

- Notifications may be clearer as a red exclamation mark in settings instead of a speech bubble

- The address and payment update section feels sparse and could be enlarged or moved to the home page

- A purchase button in onboarding or payment updates may be helpful

- Checkboxes for “Terms & Conditions” and “Privacy Policy” on the welcome screen would be useful for tracking or sharing data

Taking this feedback, these screens were revised as follows:

Final

Our next set of screens focuses on how to create a group.

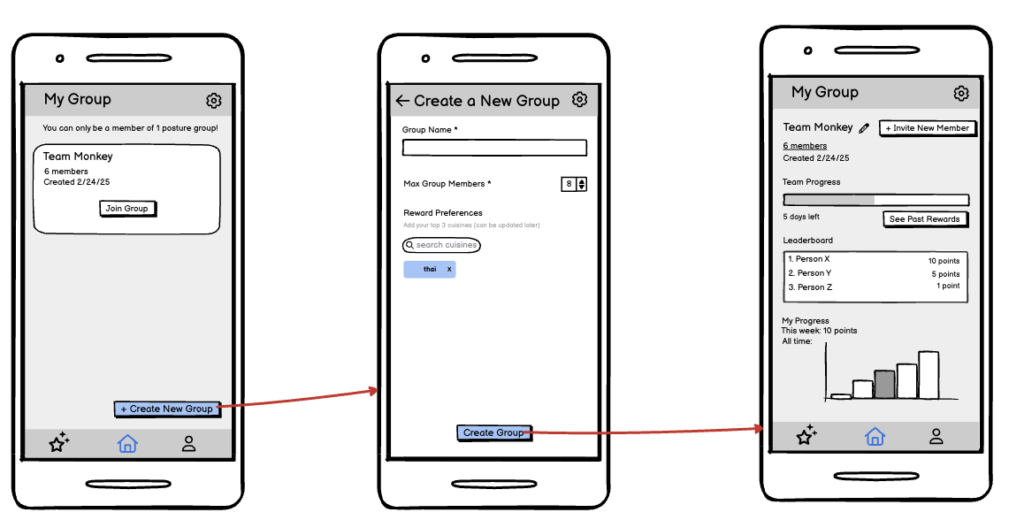

Creating a Group

Initial

Feedback

Here is a quick summary of what the team thought:

- The group creation flow is a bit confusing when already in a group. Having the initial screen blank before creating a group or renaming it could clarify the process.

- An invitations tab in the group page could help separate creating and joining a group, making it easier for users to navigate.

- Adding a history button on the home page could allow users to track their progress over time.

- The home icon placement could be reconsidered—placing it on the left might feel more standard, but centering it draws attention.

- The font size is small and could be increased along with button sizes to improve readability and usability.

Taking this feedback, these screens were revised as follows:

Final

Our next set of screens focuses on how to invite your friends.

Inviting Friends

Initial

Feedback

Here is a quick summary of what the team thought:

- The invitation flow has multiple screens and decision points, which may slow engagement. Reducing extra steps, such as selecting contacts, adding personal messages, and confirming invite statuses, could simplify the process.

- It might be helpful to see the invite before it’s accepted to better understand the recipient’s experience.

- Another option to invite friends beyond just selecting contacts could improve flexibility, such as a copyable invite link.

- The invitations sent page or the group page could allow users to invite more friends later, making the process more flexible.

- Users should have a way to check invitation statuses at any time, not just immediately after sending an invite.

Taking this feedback, these screens were revised as follows:

Final

Our next set of screens focuses on how you can check your progress.

Checking Progress

Initial

Feedback

Here is a quick summary of what the team thought:

- The bottom navigation bar should be removed on deeper pages to avoid confusion and unintended navigation.

- The history button should be larger or repositioned to improve discoverability.

- Clarification is needed on what 100% progress means if the goal is set at 90%.