by Greg Kalman, Austin Konig, Ananya Navale, Shuman Wang, Jasmine Xu

Baseline Study

Study Overview

Our baseline study initially aimed to examine the general attitudes towards late-night eating behaviors of undergraduate students on the Stanford campus. We hoped that our data collection through a diary study would reveal this to be an unwanted but unavoidable habit that developed from being in close proximity to late-night eating locations as well as from having demanding daytime schedules. The key questions we posed included:

- What is the frequency with which students consume food late at night? What foods do they generally consume?

- Why do students eat late at night so frequently? What are the student-reported causes of this behavior?

- Do they enjoy this or dislike this behavior?

- Are there aftereffects that make late-night eating less appealing in hindsight rather than in the moment?

- Have students attempted to curb this behavior, and what methods have they tried?

Upon examining the results of our pre- & post-study interviews as well as the self reports from our diary study participants, we realized that the behavior itself is not undesirable to students, but perhaps the food they consume might be the problem. Based on these findings, we shifted our focus and the perspective with which we analyzed our data towards the nutritional value of the food being consumed late at night.

Study Methodology

Conducted over the span of 5 consecutive days (Wednesday through Sunday), our diary study requested participants to complete a Google form documenting their late-night eating behavior for the corresponding night. The forms were submitted the following morning (e.g. Wednesday night food consumption → form submitted Thursday morning) to gather a holistic picture of any possible morning aftereffects of eating the night before.

These forms consisted of both objective and subjective questions surrounding the participants’ late-night and overall food consumption. Some points addressed included:

- Was food consumed at night past 9 PM; if so, what food was selected?

- When and where was the food consumed?

- How was the food acquired?

- Why was the food consumed?

- What other food was consumed during the daytime prior to the evening? Were any meals skipped?

- What were the participant’s emotions before, immediately after, and the morning after consuming the food?

Daily reminders were sent to participants to ensure completion of the forms and encourage the greatest accuracy for time-sensitive responses.

Participant Recruitment

The study focused on undergraduate students on campus, who were recruited through connections with members of the team as well as through a public paper flyer with a QR code to a screening form posted in dining halls and other public spaces on campus.

Once participants completed the screener, which assessed their eligibility to participate in the study based on the frequency of their late-night food consumption, we organized pre-study interviews to learn more about their regular eating habits and initial attitudes towards late-night eating.

Following these preliminary interviews, emails containing an instruction guide and link to the diary study form were sent to all approved participants. We had 7 students complete our diary study, with a range of ages, genders and intensities of habit.

After the completion of the study, we re-interviewed these 7 participants once more to debrief their observations and any impacts the observation period had on their attitudes towards the behavior.

Key Research Questions

Our baseline study attempted to collect data regarding the following key questions:

- How frequent is this behavior of late-night eating observed among undergraduate students?

- Is this a behavior that is seen negatively, neutrally, or positively? Why?

- Have students ever attempted to change this behavior?

- Is this a behavior that occurs due to family/home-based lifestyles that is carried over or something that begins in college?

- Are there Stanford-specific factors that contribute to the continuation of this behavior? If so, what are these factors?

Having retrieved and analyzed our results, we decided to pivot with regard to the angle we view our target behavior. Students didn’t express a desire to change the time at which they were consuming food, more so the types and quantities of food they found themselves consuming. Thus, our research questions going forward will center around:

- Why do students choose certain foods over others to consume at night?

- Why do students choose certain late-night locations or methods over others? (e.g. Late Night @ Lakeside vs. DoorDash)

- Are there trends in the types of food that are consumed from each place?

- How often is food a necessity and how often is it a social cue?

- Do the types of food consumed change based on the setting? (e.g. in dorm, dorm on-call, with friends, alone, while working, etc.)

- What do students value more: packaged healthy food or fresh junk food?

- Do students have the ability to proactively determine whether or not they will need food later at night during the day?

Our main question will be: If accessibility to healthy late-night food as a barrier is removed, will students truly choose these options over the junk options?

Grounded Theory Report

Grounded Theory 1: Late-night food consumption is a result of incompatibility between various separate aspects of an individual’s day-to-day life.

- Subtheory: Matching demanding daytime schedules with dining hall hours provides more limited accessibility than anticipated.

- In Peter’s interview, he mentioned that his friends were “all studying a particularly difficult major, which [had] them up very late. They get back at 12 after their p-set is over,” after which they would all choose to go to a location like TAP to get fries. This represents the conflict between academic demands and physical/bodily demands.

- In Tony’s interview, he noted that “sometimes I have, like, a schedule when I just don’t have time or I don’t want to go eat dinner.” This is a very common occurrence among students, especially in STEM fields, who find their classes or office hours conflicting or overlapping heavily with their eating hours, making it difficult to accommodate travel time back and forth to any dining hall or location where meal plans are accepted.

- Question: What is to blame here for “forcing” students to eat late at night? The timing of classes, the dining hall schedules, the dining hall placement?

- Subtheory: Academic responsibilities can require students to push their social commitments to later in the day when classes are almost guaranteed to be completed for the time being.

- Canyon shared that “We need a place to kind of like connect to other people. I asked a lot of my friends, they say [that] right now during winter, the light in the sky is getting dark around 5:00 PM. Around like 6:00 or so, it will get super dark. And think about the cases like, uh, after 6:00, if you look on campus, there’s like nobody on campus during winter quarter. There’s nobody.” Sometimes the timings of activities and timings of daylight create a barrier for people’s willingness to go out and be social, creating only “idealized” pockets of time—usually centered around food—to do this.

- Question: Does weather affect the types of food that students like to eat at night?

- Canyon shared that “We need a place to kind of like connect to other people. I asked a lot of my friends, they say [that] right now during winter, the light in the sky is getting dark around 5:00 PM. Around like 6:00 or so, it will get super dark. And think about the cases like, uh, after 6:00, if you look on campus, there’s like nobody on campus during winter quarter. There’s nobody.” Sometimes the timings of activities and timings of daylight create a barrier for people’s willingness to go out and be social, creating only “idealized” pockets of time—usually centered around food—to do this.

Grounded Theory 2: Food consumption is highly influenced by social norms and is in itself a highly social activity.

- Subtheory: Sometimes, individuals are pushed to eat late at night only by the suggestion of their friends, and might have chosen other activities if left to their own devices.

- Peter indicated in his interview that he goes to eat at night “Basically, whenever my friends want to… I bring it up on occasion, but usually it’s like, you know, my friends.” In this case, Peter’s own volition is not to eat at night, since he “[tries to] make sure that I have all the major food groups on my plate” and “usually try and get my two meals a day across the board.”

- Isabella also agreed that “if my friends are gonna go get a late night snack or something, I’ll get food.” Food becomes an activity that individuals are drawn into out of desire to continue being part of a group.

- Maya brought up an interesting experience that she recalled about getting McDonald’s with her friends and telling them that she was “actually not really hungry. And the friends that I was with kept being like, oh, like, are you trying to make us feel bad about, like, not eating? … And it just made me so, like, … but I also genuinely didn’t have an appetite.”

- Question: Would students eat late at night as often if they were required to do so by themselves?

- Subtheory: Getting food late at night is a social activity in itself, where the action is the bonding experience.

- Maya also noted that “if I imagine an ideal relationship with [food], I feel like it would only be when I’m in the company of friends.” Here, food becomes a built-in part of a friendship—getting food together is something associated with warmth, companionship and sharing.

- Lauren recalled “Sometimes, like, my friends will be like, Oh, do you want to go to Late Night? Um, and then we’ll end up getting, like, a cookie or something. Sometimes it’s me.” In this case, unlike in Peter’s case from the previous subtheory, the desire to get food turned into a conversation or a back-and-forth socializing opportunity.

- Canyon recounts that “A good experience might be chatting with friends, walking on the way to Arrillaga, and grabbing food right there. We’ll kind of chat until around, like, 10:00 or so.” The fun part here is not necessarily the food itself, but the time that is allotted to renewing a friendship while food becomes the means for this communication.

- Question: Is this friendship relationship with food something that built over time? Why did this relationship occur?

Grounded Theory 3: Late night food is intertwined with the continuation or completion of work as various forms of sustenance.

- Subtheory: Food, mostly sweet food, turns into a reward for a long day of work or an assignment completed.

- Canyon noted in his post-study interview that ‘You just need to treat yourself a little bit. And I think I will store, actually, more self-treating snacks.” The study made him realize this pattern in his personal late-night eating habits, and created a nudge for him to better prepare for this.

- Maya, quite profoundly, observed that “habits form as a result of constant pairing between like, a context and an action and rewarding that behavior. And I feel like that’s definitely what I was seeing, like, when I was late-night eating—was like being rewarded for doing that, you know, because I was with friends.” She very accurately identified the relationship between action and reward/celebration with respect to her specific late-night eating behavior.

- Question: What is the “rewarding” aspect of food?

- Question: Why does an effective reward, most of the time, have to be something that is unhealthy or goes against what developing a good habit/behavior would encourage?

- Subtheory: Food is a driving force that fuels work to persist for longer periods of time and keep the consumer awake.

- Lauren realized that “I think that the when I’m pulling all-nighters, I don’t think it’s possible to do that without eating”; as someone who mentioned needing to do so multiple times a quarter, this is a critical piece of information that leads back to the questions about workload and scheduling and personal timetables.

- Canyon mentioned in his interview that “The calories are very high, the sugar is pretty high. So it will keep your brain awake.” This was an interesting insight to hear directly from a participant, that there was logic towards selecting food specifically for staying awake and being able to focus.

- Food may be a necessity for some late-night activities, but does the type of food contribute as much to the level of productivity generated?

- Could the same results be achieved through healthier means?

Grounded Theory 4: Food is chosen based on its availability and convenience more often than nutritional value.

- Subtheory: Food consumed at “regular” anticipated hours of the day can lead to a reduced need to consume at night

- Lauren said that “having a normal sized dinner at like, a relatively good hour, like, kind of lowers my necessity, or, like, my interest in late night eating,” indicating that consuming late-night food is a compensatory behavior that can be eliminated.

- Question: When is the latest that an individual can consume dinner to avoid needing to eat at night while also constraining the activity within the typical dinnertime range?

- Lauren said that “having a normal sized dinner at like, a relatively good hour, like, kind of lowers my necessity, or, like, my interest in late night eating,” indicating that consuming late-night food is a compensatory behavior that can be eliminated.

- Subtheory: At this time in life, the effort to ensure a more healthy diet is outweighed by the need to perform and the desire to experience “college”.

- Peter acknowledged that “you know you’re only going to be up at 3am eating snacks, kind of during college, so while you’re here, live it up,” perfectly summarizing the general attitude towards late night snacking and eating on campus. Most students see it as a temporary measure to attend to what they deem more important (academics, deadlines, grades).

- Maya also said in her interview that “I don’t really think late night snacking is the best habit, and I feel like I let it go, because I’m in college and it’s fun and, like, it’s not that big of a deal.” This showed us the entertainment side of the story, where late-night eating became part of the college student’s identity.

- Lauren recounted her home eating habits, saying “My mom has always been … what you consider like an almond mom, yeah, so … I don’t think that the option of late-night eating was given in my home” so “in college, it was like, ‘I can do whatever I want,’” revealing that dichotomy of “adult” life and leaving behind the childhood restrictions of the home.

- Is late-night eating a sort of rebellion against the values at home, the values of adulthood?

- Will this habit persist despite students’ claim that it is a temporary behavior “just for college”?

- Subtheory: Consumers of late night food would choose healthier options if they were available.

- Canyon posed a few questions during his interview that aligned with the thoughts of “If I do have to eat late-night food, can I eat healthier? Can I eat less amount of food that I don’t feel quite full? I can’t really fall [asleep].” These were interesting observations that made us pivot our research angle towards the health of late-night food consumption.

(See our Miro board here and our full report here.)

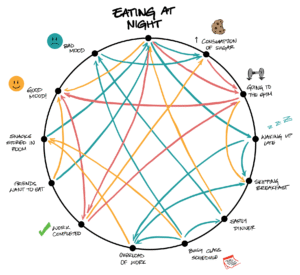

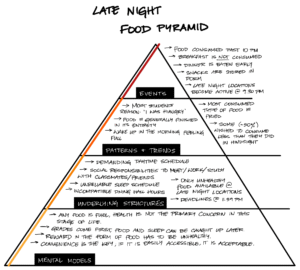

System Models

Secondary Research

Literature Synthesis

The literature on late-night eating characterizes the habit as a convergence of factors instead of a mere willpower failure. Principle among said factors are circadian and scheduling misalignments, emotional regulation and regulatory needs, and environments that promote convenience and cravings. Qualitative studies of Night Eating Syndrome (NES) describe a reinforcing cycle in which “emotional hunger” prompts eating for short-term relief, nighttime is a particularly vulnerable period, and subsequent guilt/shame exacerbates distress and future urges. Additional research on eating timing links the roles of social jetlag, overscheduled routines, emotional eating, and environmental availability to the habit, indicating that late-night eating is often a socially conditioned rational response, even when conflicting with health goals.

Multiple studies suggest that informational interventions are insufficient to match the complexities of late-night eating. In these contexts, behavioral nudges, such as repositioning healthier options, limit effectiveness and are often overpowered by immediate cravings and convenience; the additional dimension of high-temptation situations and social environments further raises the ineffectiveness of informational interventions. Evidence from related behavior-change fields indicates that interventions targeting deeper psychological mechanisms can be more effective than standard educational approaches. For example, values-alignment interventions that frame unhealthy choices as inconsistent with autonomy and social justice have led to lasting changes in attitudes and purchasing behaviors. Research also shows that making decisions as a group and publicly committing can be more effective than simply listening to expert lectures. This is because social norms, a sense of ownership, and public commitment play a powerful role in changing behavior. Another important finding is that when people limit their eating to daytime during periods of circadian disruption, they are less likely to experience increases in depression-like and anxiety-like moods. This suggests that what we eat is as important as when we eat, as timing can directly affect mental health.

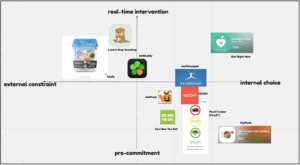

Comparative Analysis

The competitive landscape consists of three main approaches: quantification and tracking, mindset and awareness with coaching, and hard constraints or targeted retraining. Most tools excel in one area but often overlook the others.

Tracking and optimization tools like MyFitnessPal support behavior monitoring through quick logging and feedback on calories, macronutrient ratios, and progress. These features improve convenience and integration with broader health systems. However, a focus on numerical tracking can be counterproductive for those with sensitive relationships to food. As a result, some design teams avoid hard limits, deficit framing, and streak-based pressure, favoring approaches that encourage gentler self-regulation.

Coaching and mindset tools like Noom take a “psychology-first” approach, using CBT-inspired framing, daily micro-lessons, and support from coaches or group accountability. However, they often focus on weight loss as the main outcome, which may not meet the needs of users seeking to change late-night eating specifically. Photo-based and reflective journaling tools, such as visual diary products that emphasize rhythm, reminders, and non-judgmental awareness, make it easier to identify patterns but are more effective for documentation than prevention.

Constraint and retraining tools act at the moment of temptation. For example, kSafe uses pre-commitment by securing food, offering immediate results with minimal effort and a short learning curve. However, it mainly restricts access and does not address underlying causes such as stress, boredom, or circadian disruption; it can also be bypassed by obtaining new food. FoodTrainer uses go/no-go inhibition training to reduce automatic reaching for trigger foods through brief, scalable daily sessions, though its effectiveness in real-world late-night situations remains uncertain. Lighter tools like Loumi intervene at the point of temptation by offering a brief, manageable commitment and redirecting attention, making the intervention feel more tolerable and self-compassionate.es habits via reflection/education/coaching but often without moment-level prevention, or (c) enforces change through hard constraints or narrow retraining that may not address broader situational triggers.

(For more detailed reviews and research, see our blog posts on our formal Literature Review and Comparative Research.)

Behavioral Personas

These personas were created by studying a diverse pool of post secondary students during our baseline interviews, diary studies, and affinity mapping. We identified recurring behaviors and triggers related to late night eating, including academic pressure, irregular schedules, social influence, and environmental cues. By clustering these insights, we distilled complex, real world student experiences into distinct behavioral archetypes that capture both motivation and context.

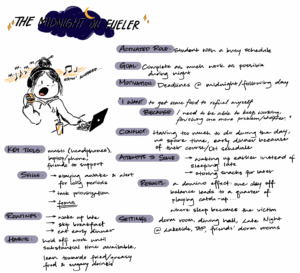

Persona 1: The Midnight Oil Fueler

“The Midnight Oil Fueler” represents a busy post secondary student whose most productive hours begin late at night, after a tightly packed day finally winds down. Characterized by her laptop open, snack or drink in hand, and half jokingly singing “Staying Alive” to keep herself awake as shown in the persona illustration, she embodies the reality of working through exhaustion.

Why This Persona Matters:

This persona matters because it encapsulates many students in post secondary schools whose academic lives are defined by dense schedules and limited flexibility. Across the timeline, moments of stress, relief, hunger, and short lived energy gains repeat in a cycle that feels familiar to a broad student population.

“The Midnight Oil Fueler” makes visible how structural demands normalize late night work, rushed eating, and sleep sacrifice as survival strategies rather than exceptions. Understanding this persona helps surface shared struggles and highlights opportunities to design support systems that align with how students actually experience their days.

Key Insight:

The Midnight Oil Fueler is driven by the pressure of dense daytime commitments and imminent deadlines, which push her to rely on late night productivity and food as functional fuel to keep going.

(See the full blog post here.)

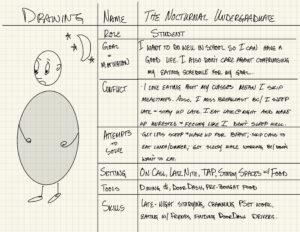

Persona 2: The Nocturnal Undergraduate

“The Nocturnal Undergraduate” is a student whose academic life is centered around late night studying and delayed routines. As shown in the persona, they regularly sleep and eat off cycle, skipping traditional meal times and relying on late night food runs or delivery to sustain long study sessions. Their days are structured around classes and work, while meaningful academic progress happens after dinner and often stretches past midnight.

Why This Persona Matters:

This persona matters because it reflects a large portion of students in post secondary schools who operate on non-traditional schedules shaped by academic pressure and limited daytime flexibility. “The Nocturnal Undergraduate” makes visible how late night productivity, irregular eating, and compromised sleep are normalized behaviors rather than exceptions. Understanding this persona helps reveal systemic gaps in campus services, food access, and study support for students whose peak working hours fall outside standard schedules.

Key Insight:

“The Nocturnal Undergraduate” is driven by the need to prioritize academic success within rigid daytime constraints, leading them to depend on late night work and irregular meals to keep up.

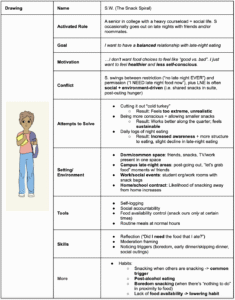

Persona 3: The Snack Spiral

“The Snack Spiral” is a senior in college whose late nights blur the line between socializing, studying, and eating. As shown in the persona, they often begin the evening feeling finished with food, only to get pulled back in by shared spaces, friends, and convenience. What starts as light snacking becomes a series of “just one more” decisions that gradually escalate into late night overeating.

Why This Persona Matters:

This persona matters because it reflects many students in post secondary schools who navigate food choices in highly social, environment driven settings. “The Snack Spiral” highlights how late night eating is rarely a single choice and more often a chain of small, context based decisions shaped by peers, availability, and fatigue. Understanding this persona helps shift focus away from individual willpower and toward the environments and social dynamics influencing student behavior.

Key Insight:

“The Snack Spiral” is driven by social proximity and late night settings that steadily erode boundaries and turn “just one more” into a self-reinforcing cycle.

Rationale for Persona Selection:

We selected these three personas because they represent distinct but overlapping late night eating patterns that are common across post secondary student life, shaped by time pressure, social environments, and academic demands.

- “The Midnight Oil Fueler”: Represents students who eat late at night primarily to sustain productivity and meet academic deadlines.

- “The Nocturnal Undergraduate”: Captures students whose entire daily rhythm shifts later, normalizing late night work and off cycle meals.

- “The Snack Spiral”: Highlights how social settings and shared spaces turn late night snacking into a gradual, unintentional cycle.

Journey Maps

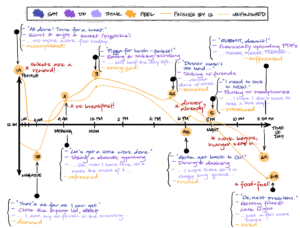

Journey Map: The Midnight Oil Fueler

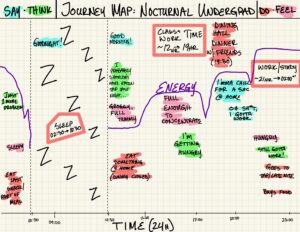

Journey Map: The Nocturnal Undergraduate

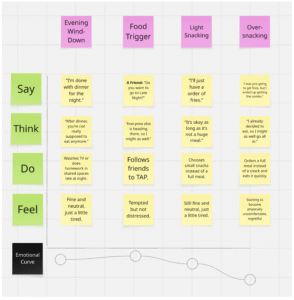

Journey Map: The Snack Spiral