Intervention Study Overview

Our overall intervention goal is to help participants make healthier late-night eating and snacking choices without requiring them to eliminate late-night eating altogether.

This goal emerged from a baseline study that surfaced several key insights about late-night eating behaviors:

- Late-night eating isn’t simply a “bad habit” — it often serves real functional and social needs.

Students frequently eat late to sustain energy during studying, work, rehearsals, or social activities, and late-night eating can also be part of bonding and the broader college experience. Because the behavior fulfills legitimate needs, interventions that frame it as something to eliminate entirely are unlikely to be realistic or effective.

Thus, the core friction isn’t whether students eat late — it’s what they eat once they do. This insight prompted us to shift from attempting to stop late-night eating toward improving how students engage with it. - The late-night food environment structurally nudges unhealthy choices.

Healthier options are often scarce late at night: dining halls close earlier, while fast food, highly processed event snacks, vending machines, and shelf-stable dorm foods dominate. Even students who want healthier options frequently default to less nutritious choices due to availability, convenience, and time pressure.

Overall, food choice is shaped not only by motivation but also by environment and accessibility. This suggests that reducing friction and increasing availability of healthier options — through choice architecture and access — would be a critical part of our intervention.

Based on these insights, rather than discouraging late-night eating itself, our intervention focuses on supporting healthier choices within this existing behavior. The goal is to preserve the functional and social benefits of late-night eating while nudging participants toward more nutritious, satisfying options by lowering barriers and improving the surrounding food environment.

Building on these insights, we developed three intervention ideas, outlined below.

Top 3 Intervention Ideas

Idea #1: “What’s on the Menu?”

Description:

This intervention involves partnering with existing on-campus late-night food providers (e.g., Lakeside Late Night, TAP) to present a modified menu that includes both healthier and less healthy options. Currently, many late-night offerings skew heavily toward highly processed foods, with very limited nutritious choices (for example, TAP currently offers only a Caesar salad as a healthier option, buried among thickshakes and burgers and fries). Expanding the availability of appealing, nutritious late-night foods addresses a key structural barrier to healthier eating.

Beyond simply introducing healthier options conceptually, the menu would be designed using behavioral nudges to increase their salience and appeal. Healthier items would feature appealing images, descriptive labeling, and prominent placement near the top of menus or under “featured” sections to increase visibility and perceived desirability.

However, due to logistical constraints and the short study timeline, it is not currently feasible for campus providers to actually introduce new healthy food items. As such, the healthier options would be simulated: if selected, they would appear as “out of stock.” This design allows us to examine how perceived scarcity or disappointment influences subsequent food decisions — for example, whether encountering unavailable healthier options increases awareness of limited nutritious late-night availability, shapes later choices, or shifts attitudes toward campus food environments.

Because this intervention does not directly increase access to healthier foods, its primary goal is exploratory: to better understand how choice architecture, perceived availability, and emotional responses to scarcity shape late-night eating behavior. Insights from this study could inform future interventions where healthier options are genuinely introduced and supported through improved menu design.

Pros/Cons:

Pros:

- By embedding the modified menu directly into existing campus late-night dining venues, the study captures how students actually respond to nudges under natural conditions — rather than in a hypothetical or lab-based scenario. This design can strengthen the ecological validity of the findings.

- The intervention does not require sourcing, preparing, or storing new food products, which keeps costs low. This makes it a practical and budget-friendly first step that can generate actionable insights for the future.

Cons:

- Repeatedly showing appealing healthy options only to reveal them as unavailable could leave participants feeling misled or annoyed. That frustration itself may become a confounding variable. Students might shift their choices out of irritation rather than because of the intended scarcity or awareness effect.

- Since participants never actually consume any healthier food, the intervention cannot produce direct improvements in diet quality or well-being within the study timeframe. Its value is purely exploratory, which may be a limitation if stakeholders expect immediate positive outcomes.

- Deliberately presenting food items that do not exist raises mild concerns about deception. Although the risk is low, this design demands careful handling during informed consent and debriefing to ensure participants do not feel manipulated, which could otherwise undermine trust and continued engagement.

Idea #2: “Future Me Ordered This”

Description:

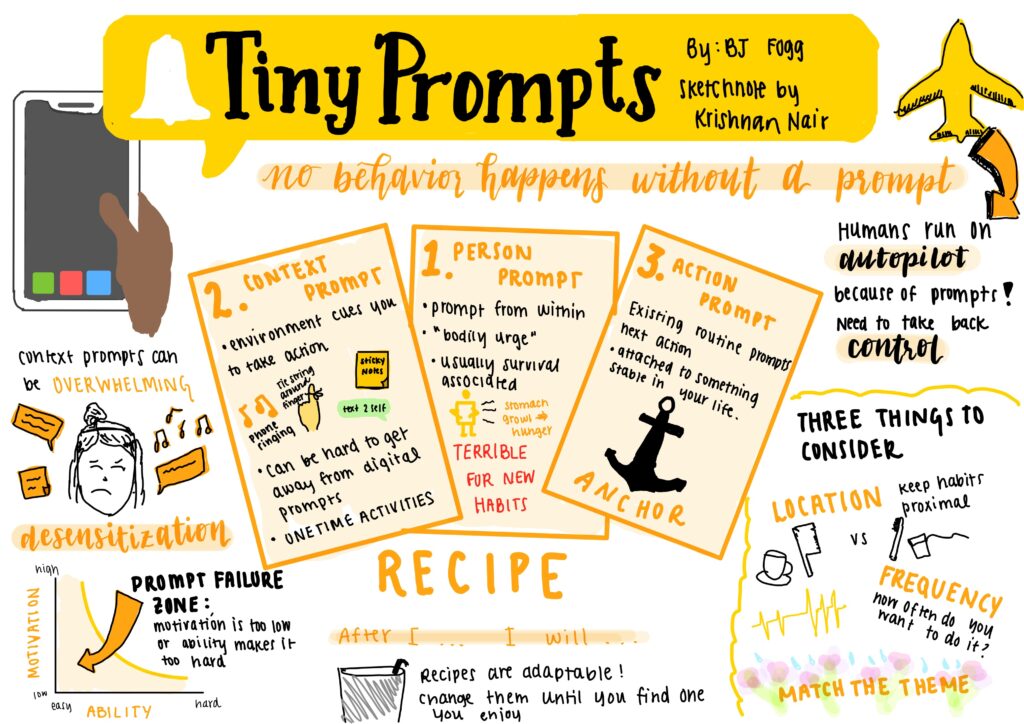

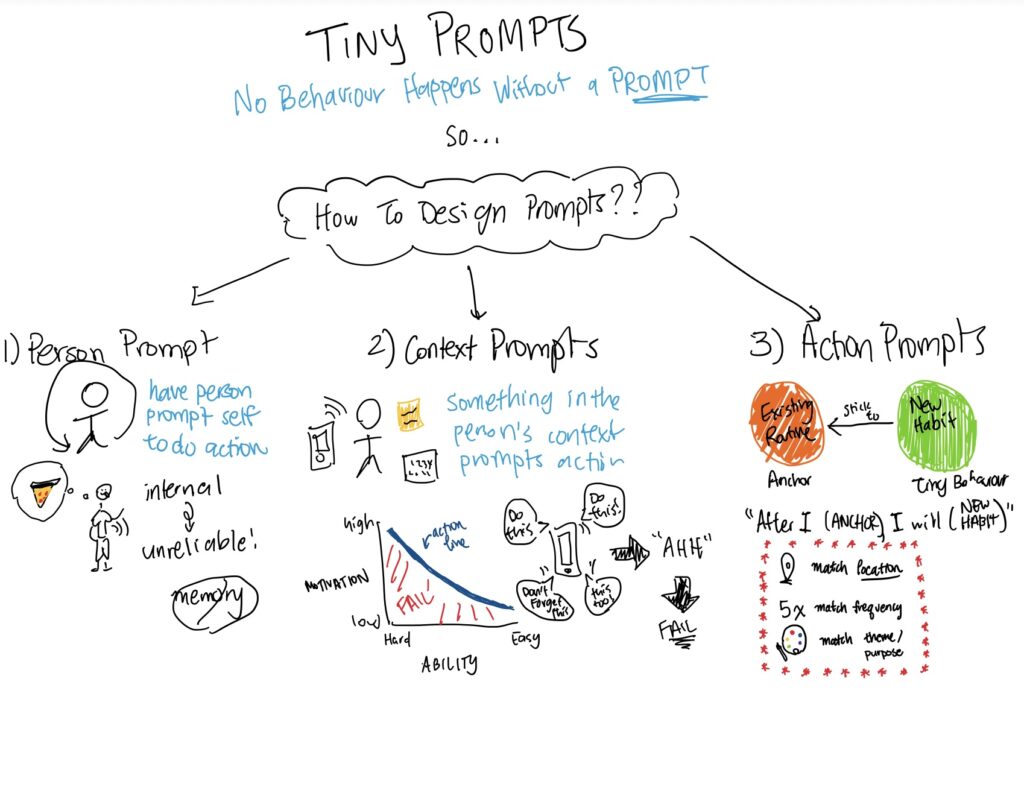

This intervention leverages pre-commitment and advance planning to help students make healthier late-night food choices before fatigue, stress, or convenience pressures influence decisions. Each morning, participants would receive a notification from an app prompting them to consider whether they anticipate staying up late that night. If so, they would be guided through pre-ordering a late-night snack or meal.

The app would walk participants through several steps: selecting a healthier food option, scheduling a delivery or pickup time, pre-paying to reduce last-minute friction, and confirming their intention through a simple commitment prompt (e.g., “I plan to follow through with this plan tonight”). Food options would consist primarily of nutritious late-night choices — such as nut bars, heart-healthy oatmeal, or other balanced snacks — provided through a partnership with Step One Foods, a healthy food company sponsoring the study.

To strengthen engagement and adherence, the intervention would include additional behavioral supports. First, light gamification and reflection features would reinforce consistency: the app would check in later that night or the following day to see whether participants followed through, prompting brief reflection on how their food choice affected energy, mood, or productivity. Consistency could be rewarded through small incentives (e.g., keeping a plant, pet, or village alive), rewarding commitment follow-through and supporting habit formation over time. Second, because social norms often influence late-night eating — students frequently eat simply because peers around them are eating — the app could incorporate optional social features. Participants could invite friends to join, make commitments together, and view shared progress or leaderboards, leveraging accountability and positive peer influence to support healthier choices.

Overall, this intervention targets multiple behavioral drivers. Pre-ordering healthy options increases ability by improving access and convenience, as the pre-order menu consists exclusively of healthy food choice, while pre-commitment reduces decision fatigue at night. Gamification, reflection, and social accountability enhance motivation, and the morning prompt functions as a trigger that encourages proactive planning before high-risk late-night moments arise. Together, these elements aim to reduce friction, support follow-through, and promote more consistent healthier late-night eating behaviors without restricting choice.

Pros/Cons:

Pros:

- Late-night food choices are often made when students are tired, stressed, and running low on self-control. By shifting the decision point to the morning, when cognitive resources are more plentiful, the pre-commitment mechanism locks in a healthier intention before high-risk moments even arise.

- This design has the potential to help students build lasting habits. The combination of gamification elements (e.g., keeping a virtual plant or pet alive), nightly reflection prompts, and consistency rewards goes beyond nudging a single choice. These features reinforce repeated engagement over time, increasing the likelihood that healthier late-night eating becomes a sustained habit rather than a short-lived experiment.

- Since late-night eating is often a social activity among college students, the optional social features (e.g., shared commitments, friend invitations, leaderboards) tap into peer accountability and positive social norms. This turns a common trigger for unhealthy eating into a support mechanism for healthier choices.

Cons:

- Building a polished app with pre-ordering, payment processing, push notifications, gamification, and social features requires significant development time and resources.

- Depends on consistent daily engagement. The intervention only works if participants remember to open the app each morning and plan ahead. Students with hectic or unpredictable schedules may skip the morning prompt frequently.

- Morning plans may not survive the reality of the night. Late-night schedules are inherently spontaneous: social plans change, appetite fluctuates, and on some nights students simply do not stay up late. A pre-ordered meal that no longer fits the evening’s reality may go to waste or be ignored.

Idea 3: “Pause Before the Pizza”

Description:

Description:

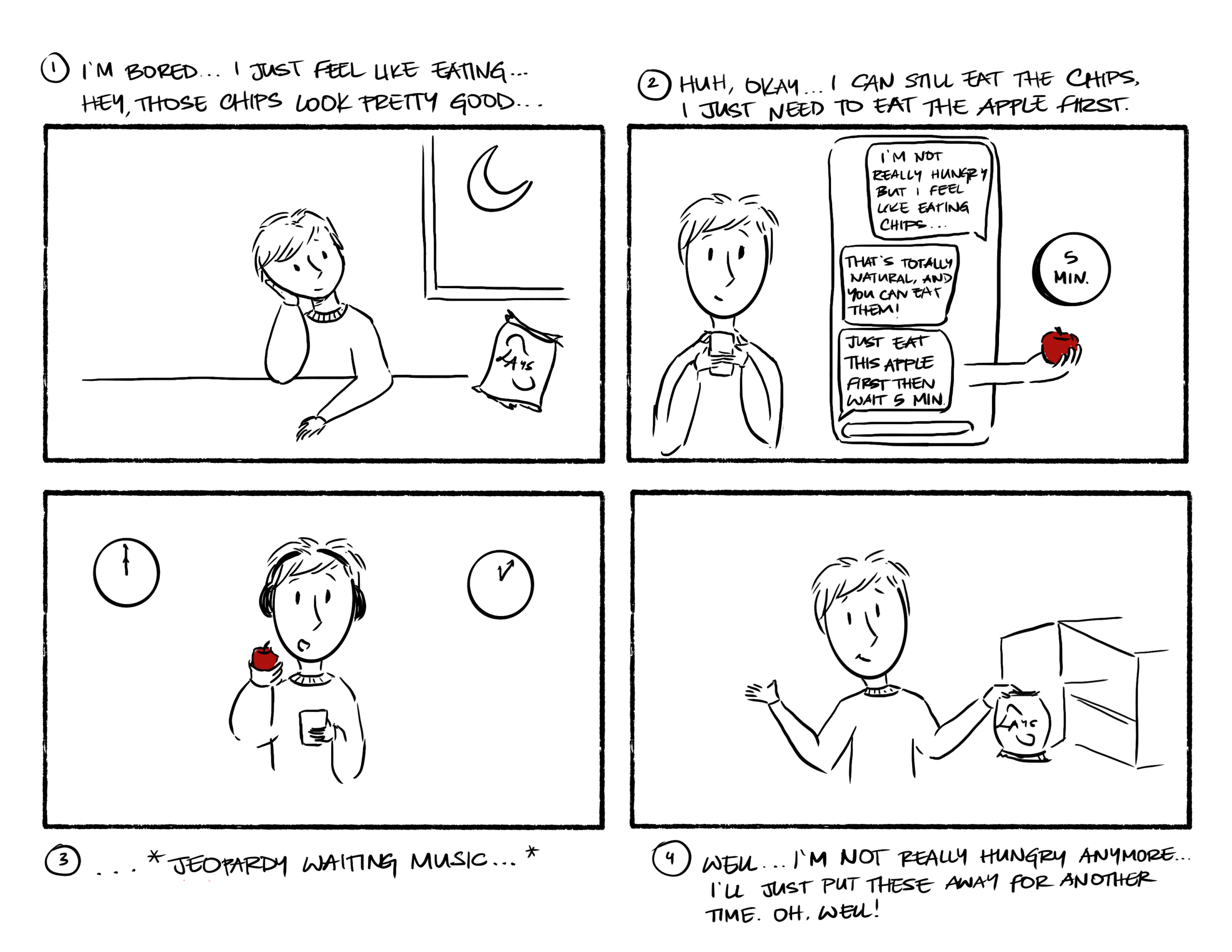

This intervention focuses on shaping participants’ immediate responses to late-night hunger by introducing a simple “healthy first” default. Participants would be provided with a selection of convenient healthy snack options to keep in their dorms (e.g., fresh fruit alongside nutritious packaged items from Step One Foods). They would be encouraged to consume one of these options whenever late-night hunger arises before deciding whether to eat anything else.

Importantly, the intervention does not restrict participants from eating other foods afterward. Instead, participants are asked to eat one pre-listed healthy option first and wait approximately 15 minutes before deciding whether they still want additional food. The goal is to reduce impulsive late-night eating while preserving autonomy and flexibility.

To support adherence, an accompanying app would provide moment-of-decision prompts. When participants feel hungry, they would tap an “I’m hungry” button in the app, which would prompt them to choose a healthy snack and initiate a 15-minute reflection timer before accessing food delivery apps such as DoorDash or Uber Eats. This creates a brief pause that encourages mindful decision-making.

This intervention leverages several behavioral mechanisms to encourage healthier late-night eating without restricting choice. Providing participants with convenient healthy snack options to keep in their dorms increases ability by reducing practical barriers to healthier eating. Making a nutritious snack the default first step when hunger arises introduces a timely trigger and draws on default effects, reducing the effort required to choose a healthier option. Importantly, participants retain full autonomy to eat other foods afterward, which helps sustain motivation and minimize resistance while gently nudging behavior toward more intentional and balanced late-night eating.

Pros/Cons:

Pros:

- The core mechanism (i.e., eat a healthy snack first, then wait 15 minutes) is intuitive and requires no complex technology or extensive vendor coordination. This simplicity keeps implementation costs low and makes the intervention easy to replicate across different campus settings.

- This intervention respects participant autonomy. Rather than restricting what students can eat, the intervention simply introduces a “healthy first” default while leaving all other options on the table. This non-restrictive framing minimizes psychological reactance and increases participants’ likelihood of accepting and adhering to the approach over time.

- Uses natural satiety signals to curb impulsive eating. Consuming a nutritious snack before deciding on additional food gives the body time to register fullness cues during the 15-minute pause. This physiological buffer can organically reduce cravings for high-calorie options and lower overall late-night calorie intake.

Cons:

- May lead to “double eating” rather than substitution. For students with strong late-night cravings or large appetites, the healthy snack might simply be consumed on top of the usual unhealthy food. In that scenario, the intervention could inadvertently increase total caloric intake instead of improving diet quality.

- Does not address broader environmental triggers. The intervention focuses on the individual moment of hunger but leaves untouched the larger contextual factors (e.g., peer pressure, stress eating, the pervasive marketing of fast food delivery apps) that drive late-night eating in the first place.

Narrowing Down: “Future Me Ordered This”

After conversations with the teaching team and internally within our group, we decided to move forward with Idea #2, “Future Me Ordered This.” We subsequently refined this concept in greater detail and developed an intervention study to test its core mechanism without requiring a fully built app. The study design is outlined below.

Goal:

To test out the concept of our solution, we are conducting a mini intervention study / pilot study to see whether pre-commitment and advance planning can help students make healthier late-night eating choices. Specifically, the study asks:

“Does prompting students to pre-plan and pre-commit to healthier late-night food choices earlier in the day increase follow-through on healthier eating behaviors compared to baseline patterns?”

Participants:

10 participants (Stanford undergraduates)

- 5 from our baseline diary study (to compare behavior before vs during intervention)

- 5 new participants (to test how the intervention works with fresh users)

Procedure:

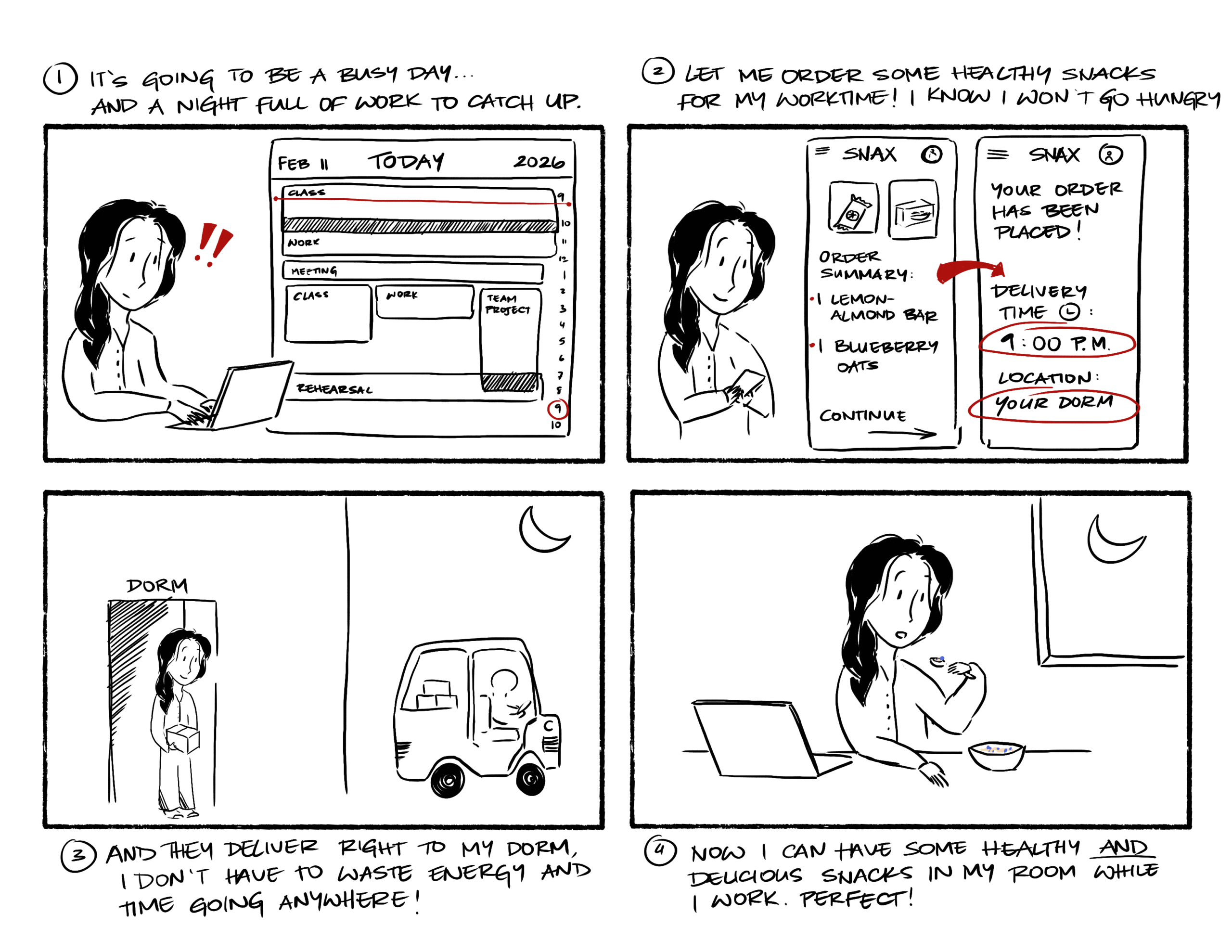

Over the course of ~1 week (5–7 days), participants will receive a Google Form every morning where they fill out:

- Whether they plan on staying up late that night

- If so, they are invited to outline the details of that night:

- When they plan on having food

- Where they plan on having the food

- What they plan on having (from a list of healthier choices provided by Step One Foods, with the option to choose their own alternative if needed — this serves as the pre-ordering/pre-planning component)

- At the end of the survey, they have the option to check a commitment box:

“I am committed to this plan tonight.”

If participants opt in to ordering food, the food they selected will be delivered before the time they specified and to the location they requested. This helps reduce logistical barriers and makes it easier to follow through with their pre-commitment.

The next morning, participants will complete another Google Form reflecting on the previous night, including:

- Whether they followed through with their commitment

- If not, why not (contextual factors, cravings, social environment, stress, etc.)

- What they might change next time

- How they felt after following through or not following through

- Their mood, energy level, and physical condition the following morning

Data collected:

We will collect both qualitative and quantitative data, including:

Behavioral/logistical data:

- How often participants planned ahead

- How often they followed through with their commitment

- Types of food consumed

- Timing and location of late-night eating

Experiential/reflection data:

- Participants’ feelings about planning ahead

- Emotional responses to following or not following through

- Perceived barriers to healthier late-night eating

- Self-reported mood, energy, and physical wellbeing

Materials Required:

We have also prepared the necessary materials to support implementation of the study:

-

A website displaying the late-night food options participants can choose from: https://latenightmenu-2a9uxtse.manus.space/

-

A Google Form to track participants’ pre-commitments and follow-through: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1das3KW-mxzY93XrQ4xzLwuI6AK8qB7c22e_2clZ6nMg/edit?usp=drive_web&ouid=114154165761662479019

-

Introductory and closing email templates: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hVF6tOGAvecOISOtAHk-8ZFqVPCCk5IaxIeeCxaPsZA/edit?tab=t.0

-

Pre- and post-study interview guides: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1VrV7OAZHmd2LguEU32oPbftQsVP9DUu8eT0-jA8vuXs/edit?tab=t.0#heading=h.ca00uwf07d7c