In “Can One Business Unit Have Two Revenue Models?” Peter Noll faces a dilemma: whether structure or flexibility should guide a company’s revenue model. As head of the Diagnostics division at Scherr Pharmaceuticals, he must merge two business units, Siiquent and Teomik, that sell similar genetic diagnostic equipment but operate on entirely different logics. The tension between them reveals how revenue models are less about pricing and more about how a company understands its customers.

Isolde, who leads Siiquent, sells to hospitals and diagnostic labs that work under strict regulations and tight budgets. Her team follows a razor and blade model, selling machines at cost and earning profits through consumables like reagents and test kits. Her approach reflects her customers’ needs for predictability, compliance, and minimal downtime. Emanuel, in contrast, heads Teomik, which caters to research institutions and universities. His customers are driven by innovation and reputation, not reimbursement codes or budget caps. He sells high margin machines and treats consumables and services as secondary. Each business model fits its market perfectly: Siiquent’s recurring revenue aligns with clinical reliability, while Teomik’s one time sales reward scientific ambition.

Peter’s instinct to impose one unified model would simplify operations, reduce internal competition, and present a clear brand identity. But forcing a single model risks flattening the creativity and adaptability that allowed both units to succeed in different ecosystems. A flexible model, as Isolde and Emanuel argue, keeps the company responsive to diverse customer needs but can also lead to inconsistency, inefficiency, and moral hazards such as Siiquent’s pay per test system that unintentionally encouraged waste. The debate is not really about pricing structures; it is about whether stability or adaptability creates more long term value.

If I were the product manager mediating this merger, I would not begin by asking which model should prevail. Instead, I would ask what shared value Scherr wants to deliver across both markets. To make the process fair, I would structure the discussion around empathy and experimentation. First, I would have both teams map their customers’ needs and frustrations side by side to surface overlap. Next, I would translate each model into a visual revenue framework so everyone can see where they align or conflict, what is complementary and what is redundant. Finally, I would facilitate small pilot scenarios where the merged team could test hybrid pricing or service models before deciding on a permanent structure. The aim would not be to find a single answer in a meeting, but to design a process that lets the best model emerge from evidence rather than ego.

About the author

Related Posts

January 17, 2022

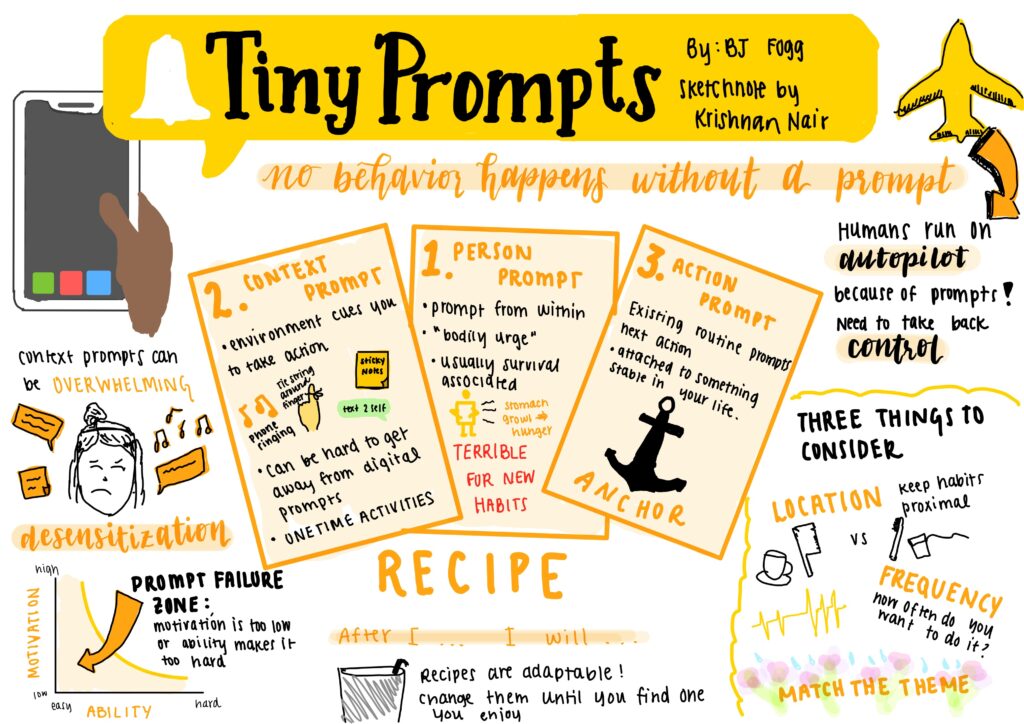

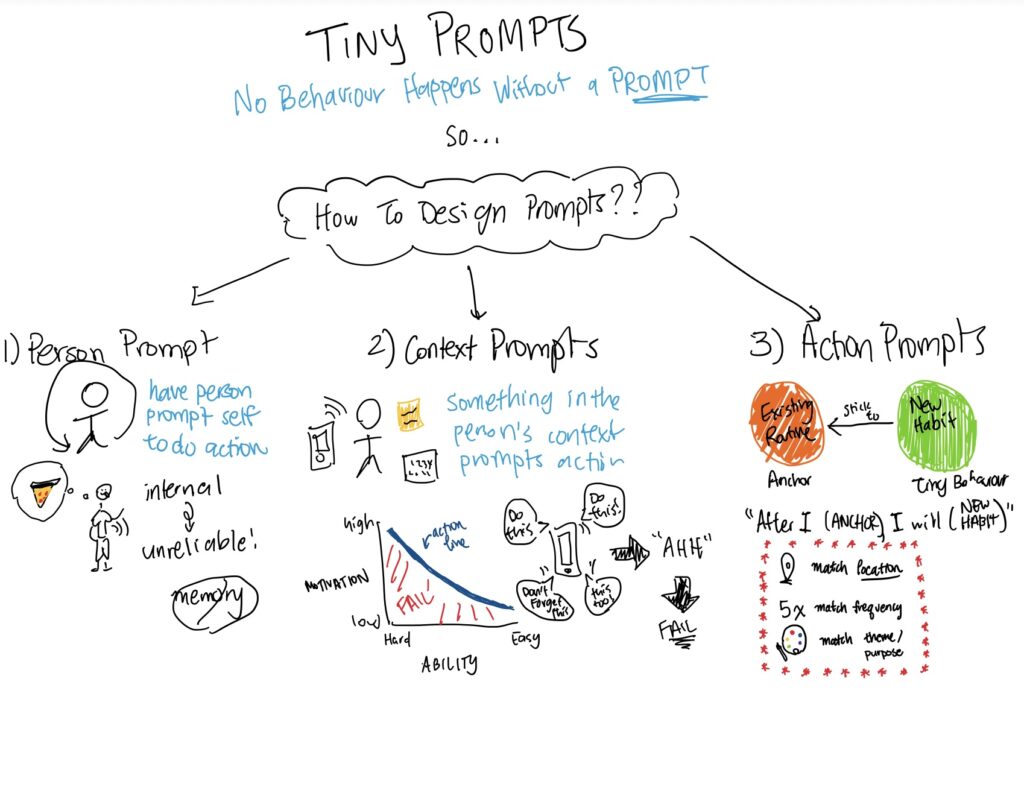

Sketchnote: Tiny Prompts

January 17, 2022

SketchNote: Tiny Prompts

January 17, 2022