Baseline Study

The baseline study was designed to understand students’ bedtime habits, particularly focusing on Revenge Bedtime Procrastination, which is the intentional delay of sleep to reclaim personal time after a busy day.

Target Participants

The target group was Gen Z students aged 18–29 who were interested in improving their bedtime schedule and routine. Participants were selected based on reported late-night device use and bedtime challenges.

Methodology

The study used interviews (pre and post) and a structured 5-day diary study to capture both behavioral data and reflective insights. It aimed to observe real nighttime behaviors and inspect the potential reasons behind. We had a total of 6 participants who completed the study from beginning to end.

Data Collection

- Screening Survey: Participants completed a short form assessing sleep habits, late-night device use, and availability. From this pool, approximately eight participants were selected.

- Pre-Study Interview (30 minutes): Conducted via Zoom to understand each participants’ typical nighttime routines, motivations, emotional triggers, and awareness of bedtime procrastination. This gives an understanding of the overall persona of the participants.

- 5-Day Diary Study (Tuesday–Saturday, Jan 20–24, 2026)

- Night Logging (10:00PM onward): Participants recorded their activities every 30 minutes until they fell asleep.

- Google Sheets was used for data collection.

- Post-Study Interview (30 minutes): Explored trends noticed during logging, emotional drivers, environmental influences, decision-making processes, and potential Hawthorne effects.

Key Questions Addressed

- What actually happens between 10PM and sleep?

- What emotions, triggers, or motivations drive bedtime procrastination?

- How do daytime stress, busyness, or lack of free time influence nighttime behavior?

- What role do devices, social interactions, and the environment play?

- Are late bedtimes intentional, automatic, emotional, or compensatory?

- Does tracking behavior change sleep patterns?

Study Excerpts

We also sent out text message blasts to participants twice a day (at noon and at 10pm) to remind them to fill out their diaries.

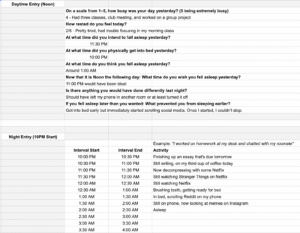

An example of one of our participants’ entries are below:

Some lines of the diary are empty because participants were told to stop logging activity after falling asleep.

Synthesis

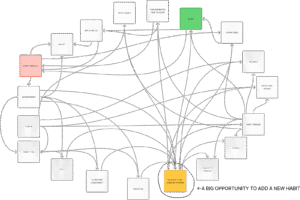

Mapping

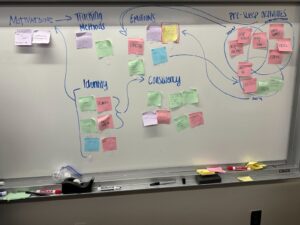

To begin our synthesis, each team member created sticky notes for 1-2 study participants, and we decided to group the sticky notes based on naturally-emerging affinity groups. Each sticky note contained critical information gleaned from each participant in our study.

The categories that emerged were:

- Tracking Methods

- Emotions

- Identity

- Consistency

- Pre-Sleep Activities

- Social

- Entertainment

- Work

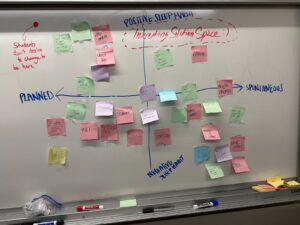

We also decided to make a 2×2 mapping of our sticky notes to identify our participants current behaviors against our two axes (Positive Sleep Habit vs Negative Sleep Habit and Planned Behavior vs Spontaneous Behavior). For example, scrolling on one’s phone late into the night would be a spontaneous behavior that is also a negative sleep habit. We identified a possible solution space for behavior change, circled in red in the image below.

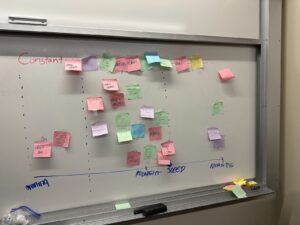

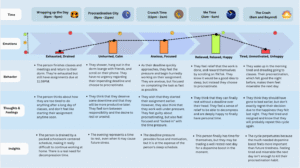

Additionally, we created a timeline of behaviors, from evening to midnight to morning, to identify and understand the progression of nighttime activities that contribute to a late night of sleep. This timeline was incredibly helpful in making concrete journey maps for our personas, which are detailed further below in this document.

Finally, we created an empathy map to identify the feelings, actions, thoughts and words of our participants, which also served to aid us in our construction of personas and in deepening our understanding of our participants.

Grounded Theory

In our study, we developed several grounded theories that explore the behavioral patterns contributing to student bedtime procrastination. These theories analyze the complex relationship between personal time, device use, and academic pressures that consistently delay sleep.

One of our grounded theories explores the idea that late-night hours represent sacred personal time for students, a time without school or work related obligations. We observed that students use night time hours to reclaim free time. This behavior serves deep-rooted needs for emotional decompression and freedom after days filled with academic demands.

Another one of our theories unpacks how students work backward from deadlines and treat urgency as the primary decision-making factor. This created procrastination of deadline-sensitive tasks that results in inconsistent sleep schedules and many late nights.

Lastly, one of our theories delves into the cycles of behavior that contribute to device-fueled delayed sleep, where device use delays sleep, causing fatigue that further depletes self-regulatory capacity the following evening.

Our grounded theory document goes more in depth on our findings and analysis and is located here.

System Models

We also created various system models to represent the behaviors of our participants and their motivations:

System Model #1: Interconnected Circle Model

System Model #2:

Secondary Research

The literature makes one thing very clear. Bedtime procrastination is not about people being unaware or careless. It is a self-regulation problem that shows up when people are tired, overstimulated, and finally alone with their time. Across studies, bedtime procrastination is defined as voluntarily delaying sleep despite knowing it will make tomorrow worse and having no real reason to stay up. People usually know exactly what they should be doing. The issue is that late at night, short-term comfort like scrolling or watching one more episode feels way more compelling than abstract future benefits like feeling rested.

Research also shows that bedtime procrastination is not a single, uniform behavior. Some people delay getting into bed at all, while others get into bed and then lose an hour on their phone. These patterns often show up in different people and suggest different intervention points. Biology plays a role too. Evening chronotypes naturally feel more alert at night and struggle to conform to schedules built for early risers. When you combine biological alertness, end-of-day exhaustion, and the desire for personal time after packed schedules, bedtime procrastination starts to look less like a bad habit and more like an understandable response to modern life.

The good news is that bedtime procrastination is changeable. Studies show that when interventions focus directly on bedtime behavior rather than general sleep education, people actually go to bed earlier and sleep better. Structured routines, small environmental nudges, and motivational support have all been shown to reduce bedtime delays and improve sleep quality. Programs like BED-PRO demonstrate that addressing the moment when people decide to stay up has ripple effects on energy, mood, and daily functioning. This reinforces the idea that solutions need to meet people where they are, especially when willpower is lowest.

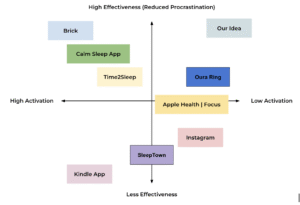

Our comparator analysis lines up closely with these findings. Many existing products either demand a lot of effort upfront or stay so passive that they are easy to ignore. Tools that are effective often rely on friction or enforcement, which can feel heavy or unsustainable. Meanwhile, low-effort tools tend to track or remind rather than intervene when it actually matters. Even everyday nighttime activities like social media or reading apps compete in this space by meeting emotional needs while quietly pushing bedtime later. Together, the research and market landscape point to a clear opportunity. The most promising solutions help people follow through at night without asking them to fight themselves.

We have charted the following companies using two axes of analysis: activation cost (how much energy the service takes to use initially) and effectiveness in reducing bedtime procrastination. We believe the ideal solution space is a service that is effective in reducing bedtime procrastination, but does not require much activation energy/initial effort on the part of the user.

Proto-personas & Journey Maps.

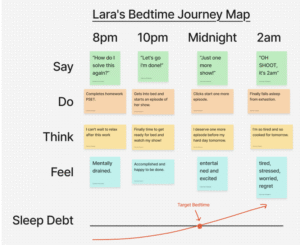

Proto-persona #1: The “Just One More” Before Bedtime

Meet Lara, she represents the student who always is doing “just one more” before bedtime. Just read one more chapter on her phone. One more game on her computer. One more episode on the show she is watching. Pretty soon it’s 2 or 3am and her sleep schedule is wrecked. This cuts into next day productivity and ultimately future entertainment time. While she tries reminders, timers, and screen time apps, she needs something that helps her avoid clicking “next episode” or “next chapter” before she unconsciously clicks and regrets it!

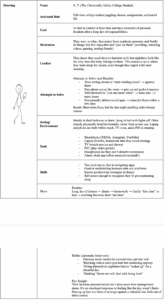

Proto-Persona #2: The Chronically Online Student

Meet A.Y., the Chronically Online College Student. A full-time student who somehow feels busy all day and free… only when it’s way too late. A.Y. isn’t bad at time management, lazy, or unaware of the importance of sleep. In fact, they know they should sleep earlier. The problem is emotional, not informational. After a long day of classes, assignments, and social obligations, nighttime feels like the only moment that actually belongs to them.

This persona captures the tension between knowing what’s healthy and choosing what feels rewarding in the moment. Scrolling, watching videos, and gaming aren’t just distractions. They’re A.Y.’s way of reclaiming personal time. Sleep gets sacrificed not because they forget the clock exists, but because staying up late feels like taking back control from a day that never really felt like theirs.

This journey map follows A.Y. through a typical day and shows how bedtime procrastination isn’t a random nighttime decision. It’s the grand finale of an emotional build-up. The morning starts with regret and exhaustion. The afternoon is powered by caffeine and survival mode. By evening, responsibilities blur together, and A.Y. starts feeling like the entire day was spent doing things for other people. That emotional “debt” builds quietly.

By the time night arrives, scrolling doesn’t feel like procrastination. It feels like earned freedom. The later it gets, the harder it is to stop, because going to sleep means officially giving the day up without ever really enjoying it. The journey map shows the real story: revenge bedtime procrastination is less about poor discipline and more about a cycle of deprivation, small escapes, and emotional trade-offs that repeat every single day.

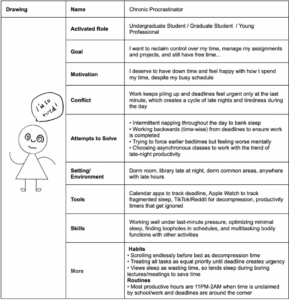

Proto-Persona #3: The Chronic Procrastinator

During the day, the Chronic Procrastinator is exhausted from obligations like classes or meetings, so they delay starting assignments until the pressure of a midnight deadline becomes urgent. Late nights are rationalized as personal time. This persona might take intermittent naps during the day and view sleep as “wasting time” or a chore to be optimized rather than rest. Overall, they keep getting stuck in this cycle because late nights lead to daytime tiredness, which leads to lower productivity, which leads to later nights. My team saw this procrastinator behavior in our interviews. This persona is helpful for understanding how students balance productivity, rest, and personal time. The journey map follows an example evening-to-morning experience my proto-persona could have.

Narrowing Down Personas:

We narrowed down our personas based on the personas we felt had desire to change their behaviors. Other personas were content with disordered sleep; however, the persona we chose is hoping for an intervention.