OneTrack explores user data, competitor analysis, and scientific literature to determine a paradigm for successful distraction intervention.

Read time: 30 minutes.

Introduction

Two weeks ago, our team set out to explore user behavior around multitasking and productivity. After one week of observing the problem space, we looked to the data for problems, insights, and solutions. Drilling down into the data confirmed some assumptions, but also brought many unexpected learnings.

Synthesis

First, we synthesized data from the Baseline Study and Market/Literature Analysis. For each field, we aggregated raw data and looked for trends, from which we were able to generalize out proto-personas and their corresponding journey maps. Patterns began to emerge.

Comparative Analysis and Literature Review

Methods

We began with our market analysis and literature review. Reviewing a total of 20 relevant research papers and competitors (10 each), we surveyed existing solutions and their potential/proven efficacy. We recorded individual insights on sticky notes and grouped ideas by category. Our most revealing grouping was the 2×2 grid. This plotted competitors and research on two axes:

- Multitasking as causal or non-causal, i.e. having effects on other abilities

- Multitasking’s effects as good or bad, measured by productivity, but with impact in other areas (like cognitive abilities)

Learnings

- Multitasking is mostly causal, and

- its effects are mostly negative.

First we noticed that both peer-reviewed research and the driving assumption of business models support the claim that multitasking does have a significant impact on other desirable behaviors, such as productivity and ability to focus. In the literature, this was explicit, with many studies controlling for other factors and finding that users performed differently when multitasking vs. not multitasking. The literature went on to suggest mostly that this had negative effects in many domains, such as student GPA, productivity, and recall ability.

In competitors, perhaps predictably, we found that many companies’ value propositions relied on selling the idea that multitasking both 1) has a significant effect on users’ abilities and 2) this effect is detrimental, not additive. Rarely today do we see products selling us on the idea that we should increase our multitasking abilities, so the literature in this case aligned with the framework in which businesses operate.

Interviews and Baseline Study

.jpg?id=da31bcdf-8e9f-4ed9-9144-0570adb69ed7&table=block&spaceId=e2756608-4053-43c8-8ec1-3bcf8ffc4ccf&width=2000&userId=&cache=v2)

We documented insights, quotes, emotions, user behaviors, from the pre-interview, baseline study raw data, and post-interview on sticky notes in Miro.

Data Mapping

.jpg?id=950127d2-ca34-4ab9-a7f2-9e7471c03f66&table=block&spaceId=e2756608-4053-43c8-8ec1-3bcf8ffc4ccf&width=2000&userId=&cache=v2)

.jpg?id=a34c122f-3561-4578-ae4b-0b4ff2b63c56&table=block&spaceId=e2756608-4053-43c8-8ec1-3bcf8ffc4ccf&width=2000&userId=&cache=v2)

Data Modeling

From the affinity map, frequency chucking, and data modeling we had three main conclusions

- Solutions to preventing distractions fall into two categories: technological silencing tools and study/planning methods

- When going from an extended period (hour+) of unproductivity to an extended period of productivity, a transition time is needed

- The standard for measuring productivity is inaccurate and detrimental to optimizing productivity

From the affinity map, frequency chunking, and connectivity model, we had a lot of data on solutions individuals have attempted to prevent distractions. Most solutions people implement are either technology-silencing tools or study/planning methods that make them more productive and naturally reduce distractions. Technology silencing tools include enabling a “do not disturb” feature, blocking websites, closing tabs, silencing notifications, and putting your phone in another room. Study or planning techniques that reduce distractions include doing similar tasks in the same work sessions, making to-do lists, and planning work sessions on a calendar. Technological silencing techniques only seem impactful if they are difficult to override. Study/planning methods, when implemented consistently, seemed highly effective.

We also noticed behaviorally that once individuals are off-task, they continue to be off-task and need a transition period before beginning an extended productivity session. Many of our participants mentioned, and the data reflected, an element of inertia. If they start the day off unproductive, they often will continue being unproductive later on and struggle to transition to being productive.

Finally, we noticed that the standard for productivity many individuals use doesn’t accurately reflect the range of difficulty and effort for each task, and this is detrimental to their ability to optimize their productivity. Productivity is defined as “effectiveness” or the “rate of output per unit of input”. Many individuals use time as their input metric and tasks completed as their output metric. For example, if someone spends ten hours on a challenging writing assignment vs. 10 hours completing four easier assignments, they would feel more productive completing the four assignments. However, only counting the number of tasks completed per time doesn’t reflect the difficulty of those tasks or the effort required for those tasks. Completing one challenging assignment should quantify as the same amount of productivity and feel as fulfilling as completing four easy tasks. The current standard of counting the number of tasks completed to measure productivity is harmful because then students belittle themselves and struggle to rest when they feel they’ve been “unproductive”.

Proto-Personas [updated]

As we continued to analyze our data, two clear profiles began to emerge from our pool of Stanford student participants. Ultimately, both types of students are hard workers who want to get the most out of their college experience. However, they differ in some of their underlying goals and motivations, which impacts the conflicts experienced by both.

There are definitely other types of students not captured by these personas. For example, some students may feel little to no motivation at all to complete work at all. This, however, is not what we observed in the Stanford students who participated in our study and is likely not reflected of a large subpopulation of students at least here. It is hard to generalize what the prevalence of this and other personas might be in other settings as we were limited in our participant sampling.

Ultimately, these two proto-personas represent a healthy average of all those we spoke to, and help to compile an image of the main multitasking paradigms.

Self-Destruct Seb [updated]

Their main goal could, in many cases, be described as to “work hard, play hard” in that they want to be successful, but they also have a higher focus on developing their social experience and connecting with those around them. This type of person enjoys working in groups and is definitely a hard worker, but they consistently find themselves distracted by social forms of communication like texting, social media scrolling, and conversations and events that come up in their life.

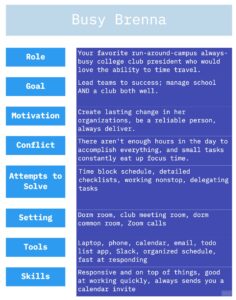

Busy Brenna [updated]

Unlike Self-Destruct Seb, they are equally motivated by extracurriculars and a million things in their schedule besides just academics. This is in many ways the classic “club president” student who ALWAYS seems to be running around doing things and just needs more hours in the day. This notion of constantly having more work than there is time for leads to the need to prioritize and cut out some work because it literally may not all be able to get done. They find themselves distracted sometimes by social communication and activities, but more often simply by other work; small tasks, emails here and there, and etc., which makes it hard for them to hone in and focus on their priorities.

Journey Mapping [updated]

From each of the proto-personas, we generated journey maps to highlight the cycles and sequences of events our personas might experience in a typical day or work session. These journey maps represent a micro-cycle in each multitasking paradigm, and capture what each proto-persona experiences at key time points.

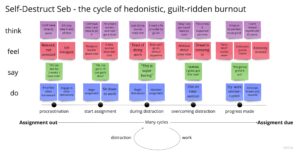

Self-Destruct Seb [updated]

Our first journey map we labeled the “cycle of hedonistic guilt-ridden burnout.” Often, people who fall into this category start tasks optimistically in hopes of getting work done quickly to go do something else. However, they can be easily distracted by social media scrolling or other social engagements like texts which quickly derail their work. Suddenly, they realize they are off task but then find themselves with little progress made. They begin working, often adapting a temporary “grind set” but are easily distracted again. These frequent distractions become frustrating and quickly burn the person out. They can, at times, lead to missed deadlines or work conflicting with social priorities.

The key insight we discovered was the cycle of how frequent repeat distractions are a critical part of this persona and that their repeating nature makes them likely to make the person tire and become frustrated with their work. This guided our ideation as it was clear from this persona that eliminating distractions from occurring in the first place would be key to assisting them, and that’d need to focus specifically on social distractions.

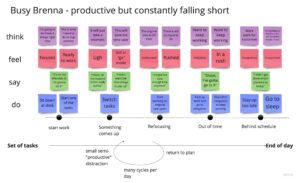

Busy Brenna [updated]

Our second journey map is labeled “productive but constantly falling short.” People who tend to follow this journey are often focused, hard workers but simply have too much on their plate. They’re motivated by a desire to lead and help others. Often, they’ll sit down to work on tasks but are distracted by emails and other work-related mini-tasks that come in and require their attention. They feel they need to do these small tasks immediately to ensure they’re not “blocking” anyone else from getting their work done and being a good team player, even if that means carrying the team. As a result of this, they may end up spending time on things they didn’t anticipate spending time on, and they may feel like they’re constantly working productively but getting nothing done. This can lead to feeling like they’re never getting enough work done, leading them to try to do even more work which can be stressful and disappointing.

The key insight here was that these individuals need help following their plan, effectively anticipating the time various things will take to complete, and executing their plan. They are less likely to become distracted by social media or social cues, though email and texts can play a major role in their distraction still. Fundamentally, both their motivations and frustrations also differ from people who embody the first persona.

Big insights

Trends, tensions, and contradictions

1. Problems trends: Categories of distractions

We observed many distraction types, which can be categorized into unproductive/productive and easy to get back on track / difficult, as illustrated in our 2×2 Baseline Study Synthesis. Going further one abstraction up, we can reasonably say that there are “derailing” and “non-derailing” distractions, whether they’re “in the name of productivity” or not.

As illustrated in our system map, “The void of distractions” topics brought up by study participants and literature outnumbers the recoverable variety, so we later discuss the great potential for category transfer.

2. Solutions tension: Problems identified vs. solutions attempted

Although specific types differ, nearly all our participants viewed distractions as “bad.” Everyone was able to identify when, where, and why they have issues staying on-track. However, despite having such explicit and detailed knowledge about their problems, most could not identify effective solutions from the plethora of options.

The majority of literature, competitors, and users suggest their own suite of solutions, for which there’s extremely varied success. The variation occurs between individuals, and throughout each day, so there’s no one solution that has provenly or anecdotally helped a large number of people on a consistent basis. The literature identified approaches that patently do not work, but is split on efficient solutions. Our participants reported needing to try different solutions on different days and wasting much of their time with unsuccessful interventions. Our participants seemed to use two types of solutions: technological silencing solutions and study/planning techniques. Although technological silencing solutions (ie turning off notifications) were useful they weren’t as impactful if they could be easily be reversed. Study and planning techniques seem to be most effective when used consistently. As much as we’d hope for one solution, individuals seem to use a combination of different types of distraction prevention techniques and there is no one-size-fits-all answer to this wicked problem.

3. Contradiction on goals: “I dislike multitasking because I want to be more productive, but measuring productivity is difficult or unpredictable.”

From our baseline studies, and reflected in our proto-personas, we found that everyone “wants to be productive.” However, no one is really sure of what this means.

There are two ends of the spectrum: Some of our participants languish their unproductive days, lost to scrolling and snacking. But on the other end of the spectrum, some of our participants report having worked all day and “gotten nothing done.”

Not only does this mean that “productivity” is no more than a feeling, but even when our participants tried to measure it, they often failed. Some report measuring by the “task completed,” and some give up because they can’t predict how long things will take. Others report variability between days as determining “whether or not today will be productive.”

Few individuals know how to break down tasks by relatively equal sized milestones, so they spearhead projects without having expected timeframes or progress indicators. Without a clear goal or stepping stones, this often leads to disappointment and only a vague sense of what they’ve succeeded or failed to accomplish.

This is further complicated by the literature, which include multiple sources that suggest that multitasking may not be possible, and data visualization of productivity is provenly ineffective. Although many popular competitors attempt to sell us on data viz reports and giving us “the control” over our time, literature suggests that universally, higher-order thinking such as “informed” decision making does not translate to action.

Possible areas for intervention

1. Problems trends: Categories of distractions

Our intervention could address the “derailing distractions” category by shifting in two ways: 1. eliminate distractions altogether or 2. prevent the user from letting distractions go on too long. Here, three insights from our findings become relevant:

- Anecdotally, users are unsuccessful at preventing distractions altogether.

- User study: Users report that not all distractions are unproductive and/or unaligned with their work goals.

- Literature review: Lit suggests that taking breaks can increase productivity and mental focus in the long term.

For these reasons, we believe that the more fruitful area of intervention would be distraction recovery. Thus, our intervention could attempt a leftward shift from “The Void” to “The Recoverable.”

tldr; OneTrack’s intervention will focus on distraction recovery > distraction prevention.

2. Solutions tension: Problems identified vs. solutions attempted

Available solutions does not seem to be the issue. Variability on what works at the individual and daily levels seem to be more problematic, and applying solutions with consistency seems even more pervasive. Our intervention could provide scaffolding for rotating different types of solutions in and out, instead of rigidly forcing users to stick to one “proven method.”

One things is clear: Users can’t be infinitely productive. Especially since this is supported by literature, our intervention could offer users time-based scaffolding to add reward or friction in intentional, pre-selected intervals.

Since there’s no universal solution, further helping users to setup this system with personalization may increase benefit. Our intervention could guide users through reflection on their anecdotally successful/unsuccessful approaches and integrate this self-knowledge into the system.

tldr; OneTrack’s intervention will incorporate time-based and flexible/personalized structure.

3. Contradiction on goals: “I dislike multitasking because I want to be more productive, but measuring productivity is difficult or unpredictable.”

Since literature and user data suggest that awareness may be impossible to cultivate, and that feelings of satisfaction range so widely regardless of outcome, our approach should leverage alternative approaches. Our intervention could help to center mindfulness instead of concrete measurement, as well as champion sustainable work habits instead of task completion.

However, since task completion is an uncompromisable feature for many, we must acknowledge some limitations of this approach. Our intervention might consider focusing on the early stages of deadline periods. We might position our intervention as a slow, sustainable alternative to a hazy and unsatisfying all-nighter. For this reason, our intervention will concretely benefit Persona 1 more than Persona 2, but may offer benefits to the second in units of satisfaction and more regular progress.

tldr; One Track’s intervention acknoweldges some concrete limitations, so positions itself as a sustainable and slow behavior change that improves productivity satisfaction.

Newly informed assumptions

- Assumption 1: We know that distractions come in many shapes and forms. However, good or bad, we now assume its recoverability is more important. We assume that we can measure this quasi-scientifically based on how long a distraction takes away from the task at hand.

- Assumption 2: We will first test if distraction recovery is an appropriate and sustainable solution. We assume that this is the basis of a strong intervention. We further assume that adding personalization will make our approach more effective at a later stage.

Intervention Study

Ideation Round 1

We conducted the ideation phase in two separate rounds. The first round was based on our findings from the literature review and the comparative analysis. There were three key study result goals that we based our ideation process on.

Insight 1: the importance of focusing on a single task, or multiple related tasks in order to boost productivity and efficiency. Insight 2: the importance of taking breaks in between work sessions in order to avoid burnout, and boost focus and satisfaction. Insight 3: identifying the triggers of am undesirable behavior, and having interceptions to redirect the habit once it has started.

In the first round, each team member contributed 5 ideas, and we voted to determine the top ideas. The image below depicts the ideas we developed on Miro as well as the results of the first round of voting.

Ideation Round 2

For the second phase of the ideation, we took the top voted solutions and re-evaluated them based on baseline study and synthesis. We took more nuanced view that multitasking can be necessary, and what we seek to optimize is the user’s ability to bounce back to the main task after shifting tasks.

We voted on the 3 intervention themes informed by synthesis, personas, journey maps and secondary research ideation:

Off-task check ins

The user catches themselves engaging in a distraction, and engage in a check-in habit instead, such as meditation. This is primarily based of research around identifying the triggers behind undesirable habits and reprogramming them through intervention.

Buddy study

We link up users who want to work together, have them set goals and intentions for the session, work together, and check in at the end of the session. This is informed primarily by research on parallel play for kids with ADHD (parallel play: where children play side by side but do not attempt to impact or interfere with each other’s session), and having an accountability partner.

Interval timer

A user enters how long they want to work for and our system incorporates breaks into their work sessions. This is heavily informed by studies around the effectiveness of breaks, the limited attention span of humans, and how our attention and productivity begin to have dwindling returns beyond a certain amount of time.

For the final phase of the voting, we selected our top three solutions by having one from each overall theme that we discussed. Below are the results of that voting process.

For each of our top three ideas, we drafted the pros and cons of each, both based off of the research we did, its potential effectiveness within our target audience as well as of how feasible the implementation would be in the remaining weeks of this class. Below is the general analysis of each of the ideas:

1. Meditate each time you feel a distraction coming on

Pros

Meditation may intercept the distraction, allowing for the recovery we’d like to investigate. Since its success relies on habit formation, combination with a time-based scaffolding system could help to overcome the initial cold start problem, and work to build sustainable behavior change.

Cons

Meditation may be slightly distracting, as it requires the user to focus on meditating, and detracts from their original task. Additionally, it’s very easy to ignore prompts and begin a derailing distraction during the wait time.

2. Accountability through virtual buddy study sessions

Pros

Communal study provides positive reinforcement and motivation — a source of “body doubling” that aids many people with ADHD to complete their tasks. This could also further help the pedagogical process because collaboration and peer-to-peer learning reinforces material. Finally, it’s easy to implement using Zoom.

Cons

Getting an accountability partner depends on the availability of others. (You may not get a work partner at each specific time interval you want to work for). Additionally, it relies on the accountability of others not to distract you.

3. BeReal for productivity

Pros

The random timing of BeReal allows users to get an accurate insight of whether they’re productive or not. Much like the popular app, it’s quick and easy to complete and can be used socially as a way to foster accountability. This app leverages the time-based insights that we discovered in our synthesis.

Cons

The app itself could be a distraction. Alternatively, the prompts could be ignored in favor of a derailing distraction. Finally, check-in photos might disrupt people in a flow state.

Final Decision

Our final decision was the BeReal for productivity, where the user sets up a work session and the app sends random check-ins where the user would have to either take a picture of them working, or log what they were doing when the timer goes off. We also combined this with the off-task check-in idea where when the user catches themselves being distracted, they can engage in a short meditation exercise to refocus and recharge before diving back into their work.

Intervention Study Plan

The intervention study aims to take a nuanced view of multitasking, recognizing that it can be necessary and/or productive, and seeks to optimize the recoverability of task switching.

Participants

Participants can be either self-identified procrastinators or students in situations where they face challenging tasks. Challenging could describe tasks that are large, difficult, or that they’re usually “unproductive” at. Participants would ideally have tried interventions before and now aim to see sustainable and incremental change in their satisfaction with productivity.

Study Protocol

Participants will be asked to complete work session check-ins using a combination of photo documentation, re-centering survey questions, and mindfulness meditation.

Mindfulness Meditation

Participants will be asked to practice mindfulness meditation when they feel distracted during their work. The meditation will involve focusing on their breath, body sensations, and the present moment.

Refocus

After the mindfulness meditation, participants will be asked to refocus on their task and continue working. They will also be encouraged to use mindfulness techniques whenever they feel the urge to procrastinate.

Follow-up

Participants will be followed up after 1 week to assess the long-term impact of the intervention on their procrastination habits.

Data collection and analysis

The data collected from the photo documentation, survey, and mindfulness meditation will be analyzed to assess the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing procrastination and increasing productivity.

Photo documentation

Participants will take regular prompted photos throughout their work session to stay accountable. This will serve as an interval timer.

Survey

As a part of the study (not the intervention), participants will be asked to fill out a survey after each check-in to evaluate their feelings of productivity for that day.

Key questions

Our intervention changes the ordinary paradigm of multitasking, recognizing that it can be necessary and/or productive in some instances, and seeking to optimize the user’s ability to bounce back to the main task after shifting tasks.

In this study, we seek to answer questions around this new approach:

Can we collect evidence that the recovery method is personalized as less important to sense of “productivity”? And that scaffolding for consistency is more effective?

Comments

Comments are closed.