Last time we analyzed company profiles. Now we draw re-contextualized insights.

Categories

For this reason, we explored businesses that offered some kind of anti-multitasking solution, ranging from small-scale one-habit to multi-feature cross-platform solutions. They clustered in four general categories:

- site, app, and distraction blockers

- automating time-management and schedule automation

- awareness increasers (data visualization reports)

- and mindfulness habit-makers

(For more on each company, skim our competitor blog post.)

Synthesis and Sense-Making

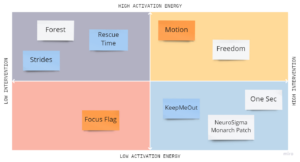

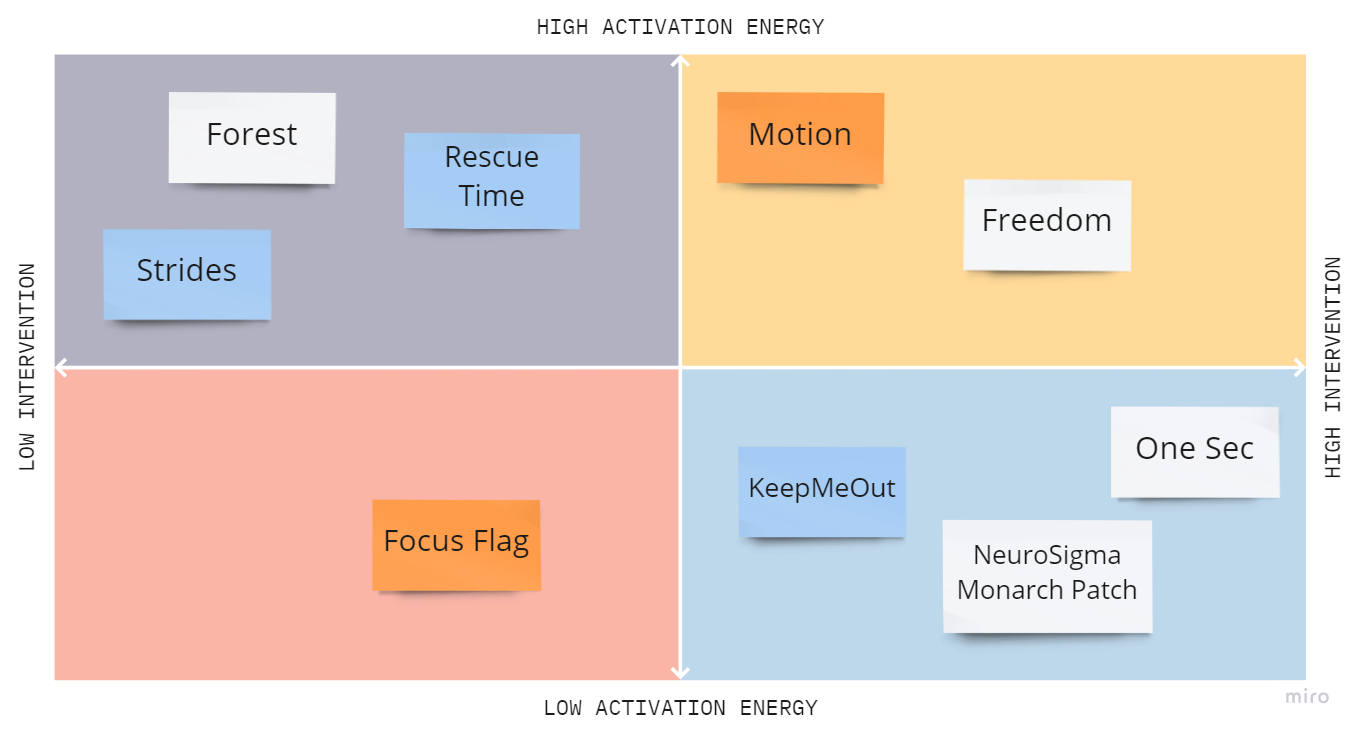

Our initial analysis found one useful way to map competitors over two axes, activation and intervention. Activation refers to the amount of energy required from the user to utilize the product whereas intervention is how effective the product is in terms of enhancing attention and productivity, either in the background or disruptively.

Although we challenged the conventional paradigms around multitasking and distractions later in the project, we did continue to assume that a low-activation and high-intervention (or efficacy) solution would be most effective.

As further analysis, we turned to strengths and weaknesses. Aggregating over companies, we found several helpful trends:

Strengths

In general, our competitors targeted sustainable habit formation. Some techniques were gamification streaks and scheduling: Apps like Forest, Motion, and WatchMinder directly addressed habit formation; while apps like Muse and OneSec indirectly targeted mindfulness, hoping that this would lead to habit formation.

Several competitors also leveraged tools like AI and automation to create a personalized approach. While almost all competitors attempted to create personalized UI through customization (whether it be creating a schedule, selecting specific distractions, or tracking your activity and preferences), some apps like Motion took a “smart” approach to automate some of this personalization.

Weaknesses

Since we conducted our literature review in tandem, we were able to identify very early on that some products would not work, and continued to sell people on myths around productivity. Experimental design proved many times over that techniques like data visualization and goal setting have little to no effect on reducing distractions (RescueTime, Freedom, Strides). Since goal setting’s flaw is based on the idea that people cannot apply cognitive effort to simply override bad habits, by extension, this problematized some of the gamification and social-pressure strategies (FocusFlag, Forest) that relied on consistent motivation to spur user behavior change.

As we would later contextualize with our Baseline Study, nearly all competitors’ central design concept was distraction prevention. Our observed user behavior revealed that distractions happen. Users override app-blockers and abandon formerly set goals because their environment, motivations, and mental state change constantly. Sometimes friends enter the room, or fatigue sets in, or an important off-task activity arises. As seen later in our process, this motivated us to shift behavior change topics to distraction recovery.

Relatedly, and building on the ineffectiveness of cognitive brute-force, they used external motivators to incite behavior change. Whether by positive or negative reinforcement, every app’s intervention was limited by its assumption that external motivation is sufficient.

Furthermore, few apps accounted for diverse distraction types. As we found in our Baseline Study, people are rarely distracted by the same things, even on an individual level within the same day. Thus app-blockers and social indicators addressed some of the common issues, but were too narrow to work for most users. They personalized distractions in the wrong way, operationalizing personalization with custom blockers for websites, as opposed to individual distraction types.

Open Market and Distinguished Product

Each of these strengths and weaknesses made perfect sense in the original paradigm, but we found them generally to rely on outdated information and common myths around productivity.

From insights in competitor research, literature review, and our Baseline Study, we refocused our energies towards distraction recovery as a universal solution for individual problems. Instead of eliminating specific distractions, we saw an opportunity to change the paradigm. Ours recognizes that multitasking can be productive, necessary, and unavoidable, and task switches and distractions can be hard to predict. Furthermore, productivity is difficult to measure objectively by “distractions blocked” or even “tasks completed” and difficult to measure subjectively by “felt productive” and “felt unproductive.”

Comments

Comments are closed.