Problem Domain and Motivation

Our problem domain is productivity. Our team sought originally to tackle multitasking because of its frequent disruptions to productivity and the public consensus that it’s a desirable behavior to change.

We initially operated on these assumptions, seeking to reduce multitasking; however, informed by literature, market research, and our study, we later drilled-down into distraction recovery as a better intervention, preserving some key learnings from early stages. Specifically, we discovered that increasing productivity requires recovering from individual, derailing distractions consistently, and measuring success may prove more difficult than we’d thought.

Baseline Study

Target Audience and Initial Info

We targeted students, focusing research on study/work habits, particularly related to technological distractions. The screener survey was used to filter for participants interested in learning more about their work habits and who use devices in their work. Additionally, participants were asked if they were comfortable recording themselves, as screen recording is one of the data collection options.

In pre-study interviews, participants were asked about their experience with behavior change, general productivity habits, and common distractions they engage in.

Protocol

To gain basic information on students work and distraction habits we gave study participants the option to keep either a diary or collect diary and screen recording data, which they would send to the us daily. Each time the participants sat down to work using a screen device, they were instructed to:

- Record the time, intended screen time, and intended activity.

- Begin screen recording, including any screen used. If they intentionally retired from the activity for more than 20 minutes, they were instructed to stop the recordings.

- Update a notepad whenever they went off-task, indicating what the activity and time spent.

Synthesis

Data Mapping

Data Modeling

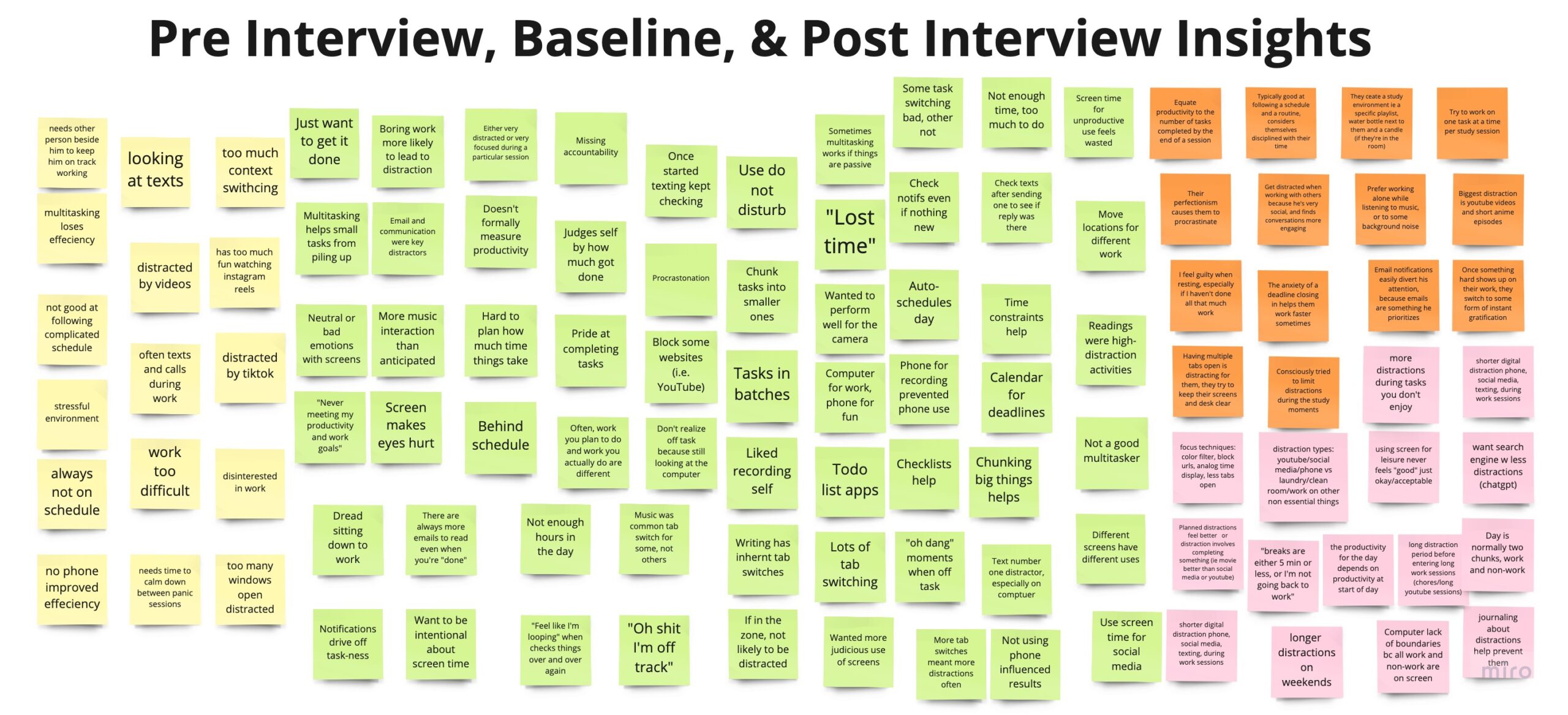

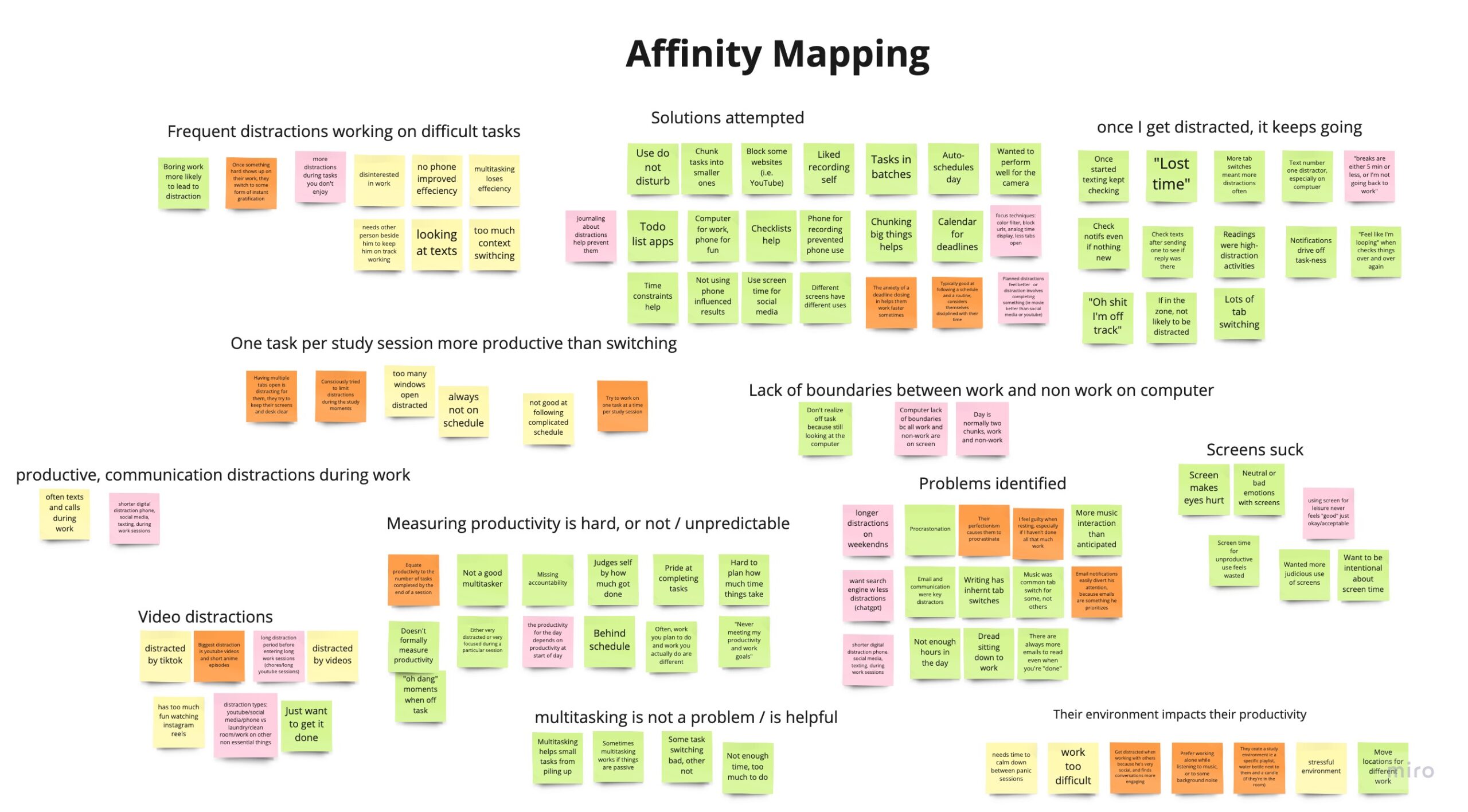

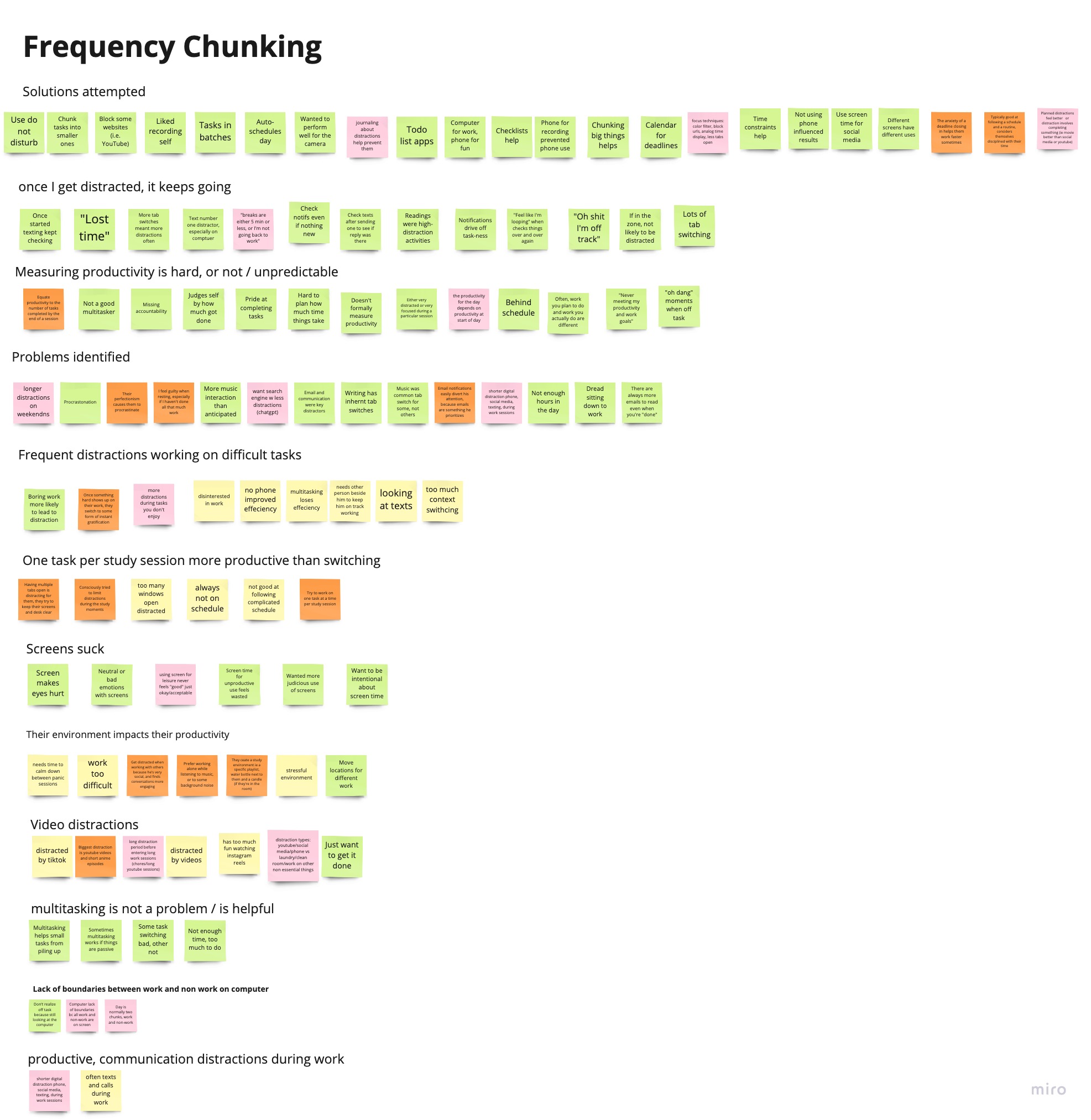

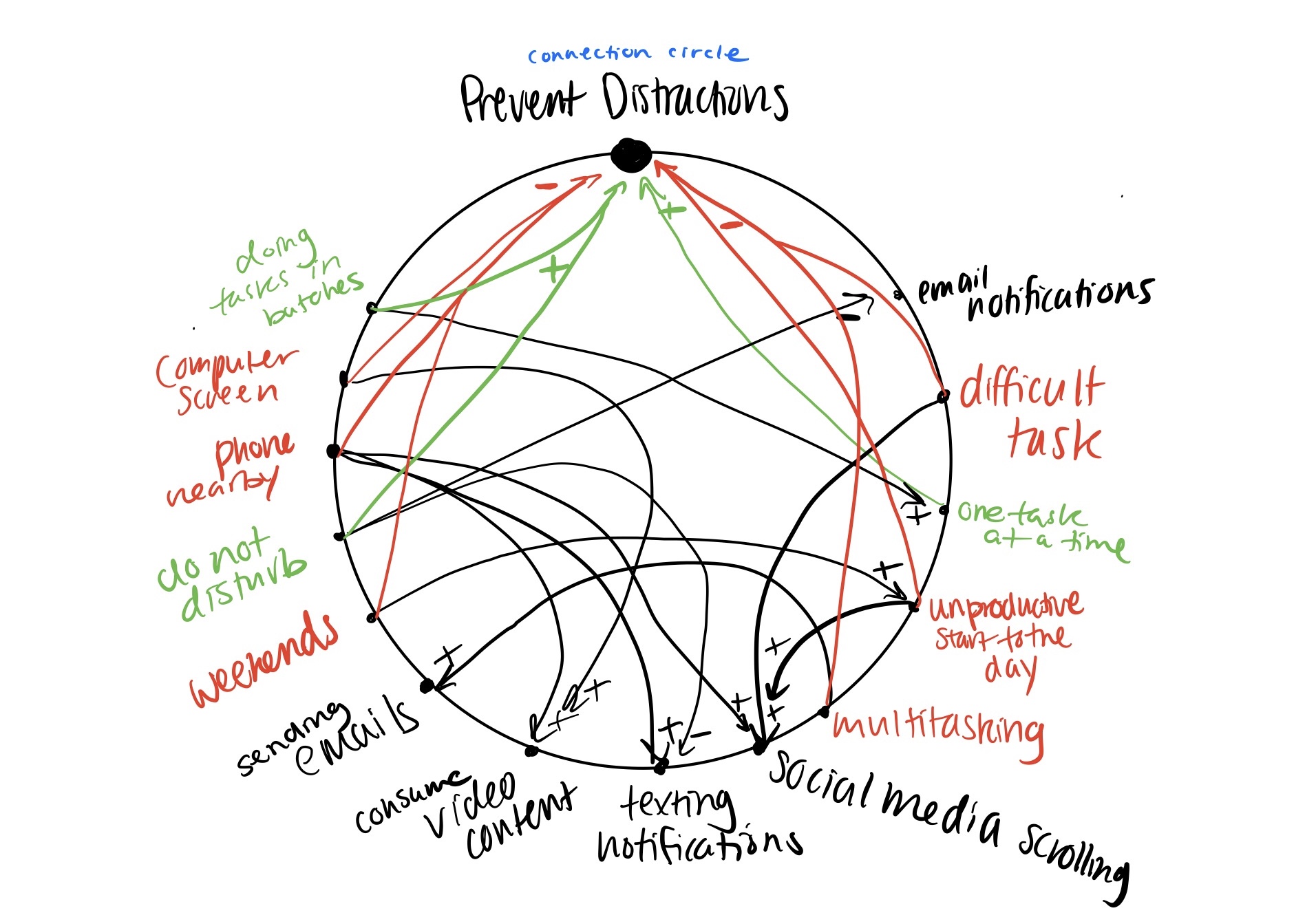

We documented insights, quotes, emotions, user behaviors, from the pre-interview, baseline study raw data, and post-interview on sticky notes. From the affinity mapping, frequency chunking, and data modeling we gained three main insights:

Distraction prevention solutions fall into two categories: technological silencing tools and study/planning methods

In the connectivity model, there are two categories of distractions: “pure distractions”(ie social media) and “off-task productive distractions”( answering emails). Additionally, from the affinity map, frequency chunking, and the green labeled nodes of the connectivity model, we identified two types of distraction reduction solutions: technology-silencing tools (ie “do not disturb”, website blocking) and study/planning methods (todo lists, time blocking). The study found that technological silencing techniques are only effective if they are difficult to override, while study/planning methods that help people inherently improve their focus and consequently reduce their distractions are highly effective when implemented consistently.

Going from an extended period (hour+) of un-productivity to an extended period of productivity requires transition time

We noticed behaviorally that once individuals are off-task, they continue to be off-task and need a transition period before beginning an extended productivity session. Our participants mentioned, and the mapping data reflected, an element of inertia. Starting the day unproductively, means you’re likely to stay unproductive, and require transition time before being productive.

Standard for measuring productivity is inaccurate and detrimental to optimizing productivity

Our data showed that most people measure daily productivity based on the number of tasks completed. Consequently, for example, individuals feel accomplished after a day of errands and feel frustrated after spending a day on one activity (ie writing an essay). Alternative productivity measurements, such as measuring the number of challenging tasks completed, would help individuals optimize their productivity with challenging tasks and help them feel accomplished.

Moving forward

- Prioritize designing an intervention that is a study/planning-based tool since those are more effective at reducing distractions.

- Although many individuals experience transition times before beginning a work session, this is a separate issue from maintaining focus. Since our primary objective is how to maintain focus during a work session, our intervention must be centered on the problem of maintaining focus, not initiating focus.

- We will create a solution that encourages and acknowledges incremental progress rather than only rewarding the number of tasks completed

Literature Review

As our first stop in the problem domain, we reviewed existing literature on multitasking, productivity, task switching, and attention.

Since the literature were empirically backed, our discoveries here were straightforward. At first we found that the scientific paradigm around multitasking initially confirmed the things in the public consensus: Multitasking has negative effects on performance and feelings of productivity. Literature’s deep dive into distraction prevention revealed the efficacy and inefficacy of certain tools, which proved greatly useful in our analysis of competitors.

Finally, more recent literature in both productivity and attention demonstrated that multitasking may not be all that problematic, and furthermore may not be possible: New framing of task switching helped to explain how “multitasking,” as a theory of split attention, is infeasible, and that task switching instead makes up the majority our modern digital lives. This framework did not cast negative light on task switching, but suggested that it can and must be designed around as a part of any modern productivity tool. While we were not able to immediately contextualize this information, as you’ll read later, it significantly bolsters our decision to switch from multitasking to distraction recovery behavior change, as well as why our new suggested paradigm might prove more useful.

For more information, skim our primary literature review.

Comparative Research / Analysis

Categories

For this reason, we explored businesses that offered some kind of anti-multitasking solution, ranging from small-scale one-habit to multi-feature cross-platform solutions.

(For more on company profiles, skim our competitor blog post.)

Synthesis and Sense-Making

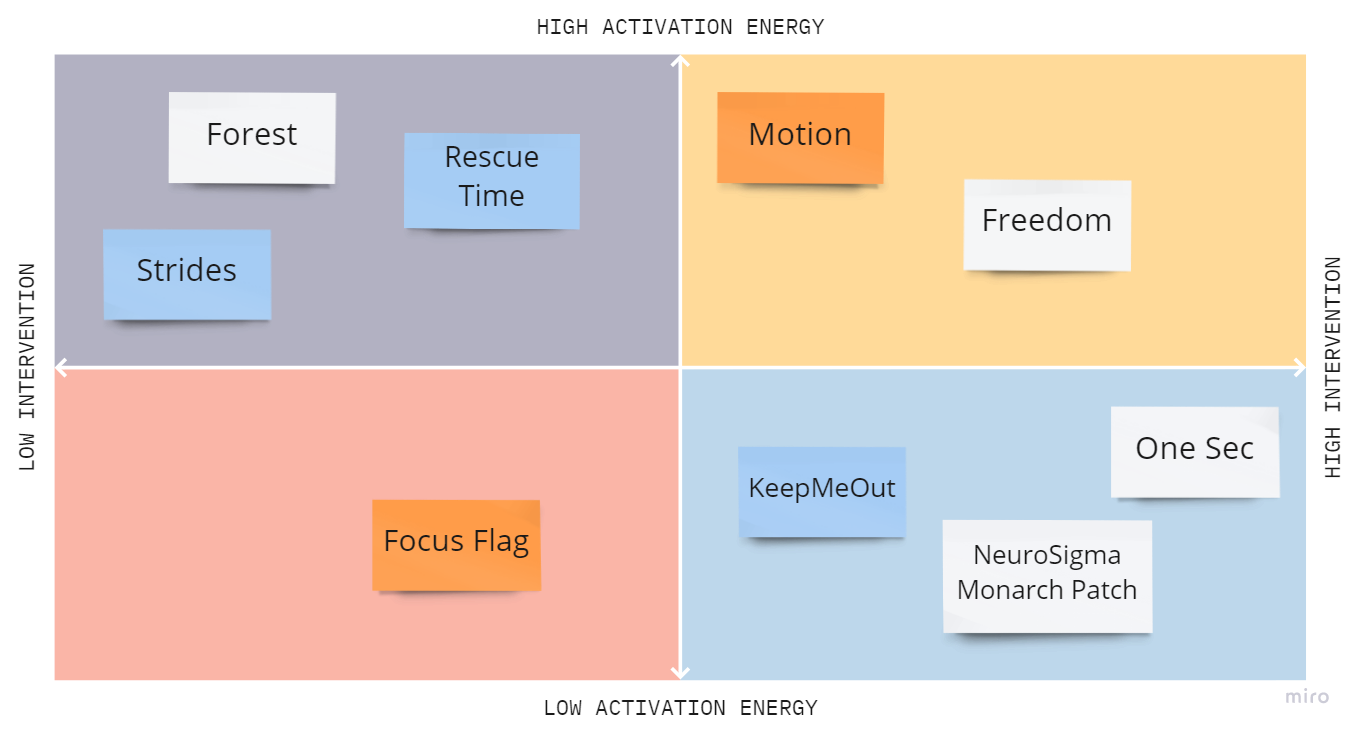

Our initial analysis found one useful way to map competitors over two axes, user activation energy and intervention strength.

Although we challenged the conventional paradigms around multitasking and distractions later in the project, we did continue to assume that a low-activation and high-intervention (or efficacy) solution would be most effective.

Aggregating over companies, we found several helpful trends. In general, our competitors targeted sustainable habit formation and automation tools t create personalized approaches. Weaknesses included solutions that have been disproven, assuming distraction prevention as the most causal to increased productivity, and the use of narrow/external motivators to spur behavior change. For details, read our competitor blog post.

Open Market and Distinguished Product

Each of these strengths and weaknesses made perfect sense in the original paradigm, but we found them generally to rely on outdated information and common myths around productivity.

From insights in competitor research, literature review, and our Baseline Study, we refocused our energies towards distraction recovery as a universal solution for individual problems. Instead of eliminating specific distractions, we saw an opportunity to change the paradigm. Ours recognizes that multitasking can be productive, necessary, and unavoidable, and task switches and distractions can be hard to predict. Furthermore, productivity is difficult to measure objectively by “distractions blocked” or even “tasks completed” and difficult to measure subjectively by “felt productive” and “felt unproductive.”

Personas and Journey Maps

Proto-Personas

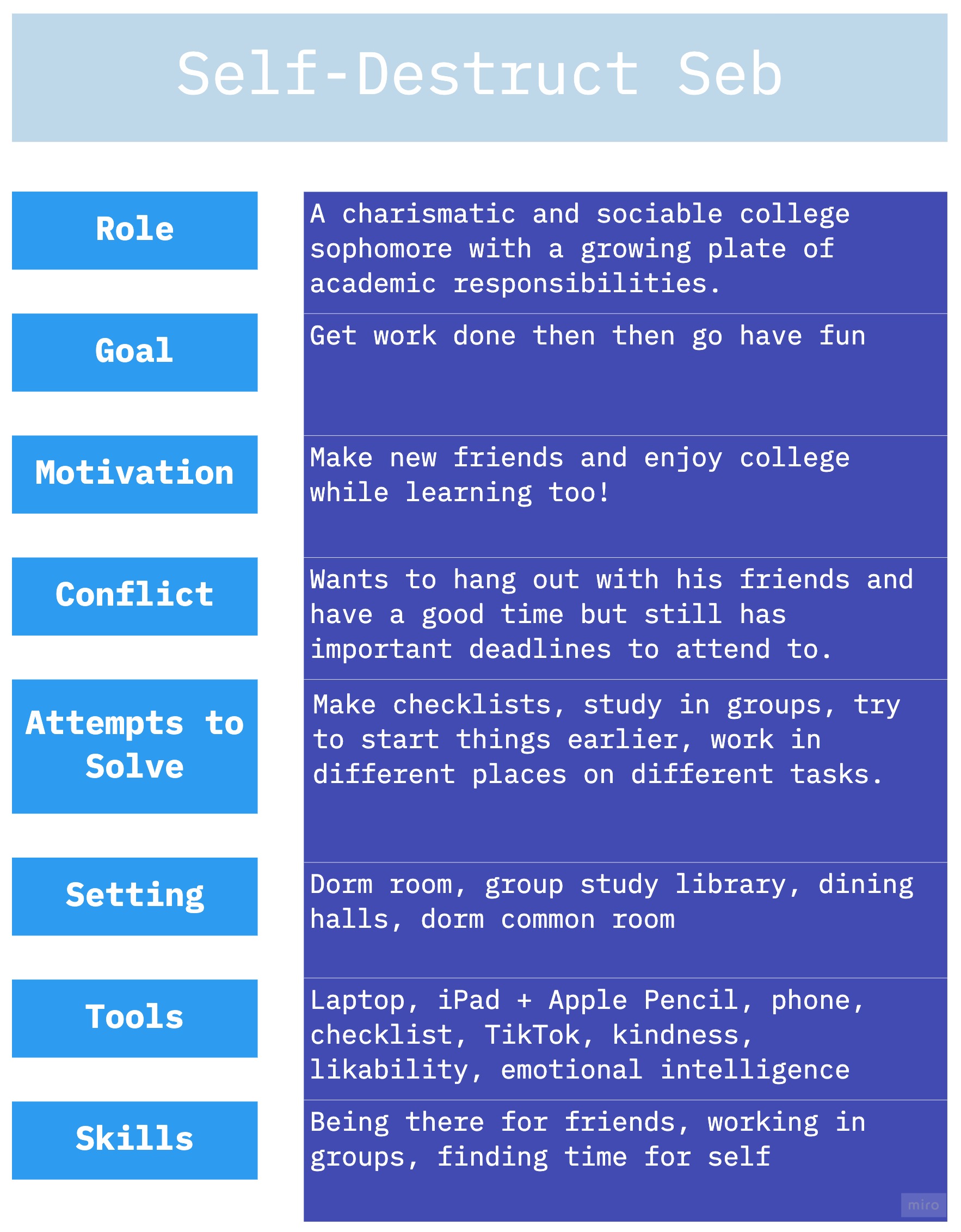

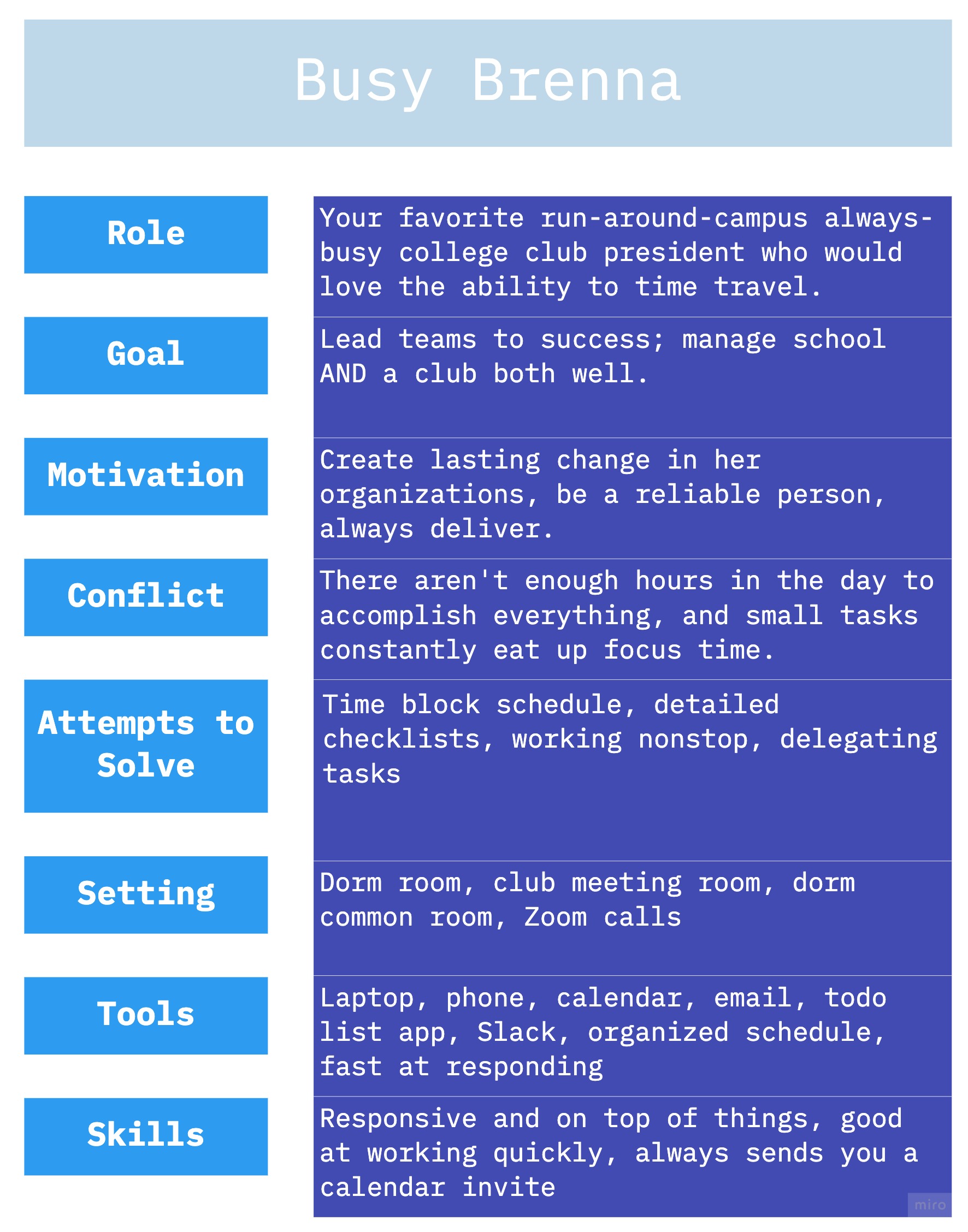

As we continued to analyze our data, two clear profiles began to emerge. Ultimately, both types of students are hard workers who want to get the most out of their college experience. However, they differ in some of their underlying goals and motivations, which impacts the conflicts experienced by both.

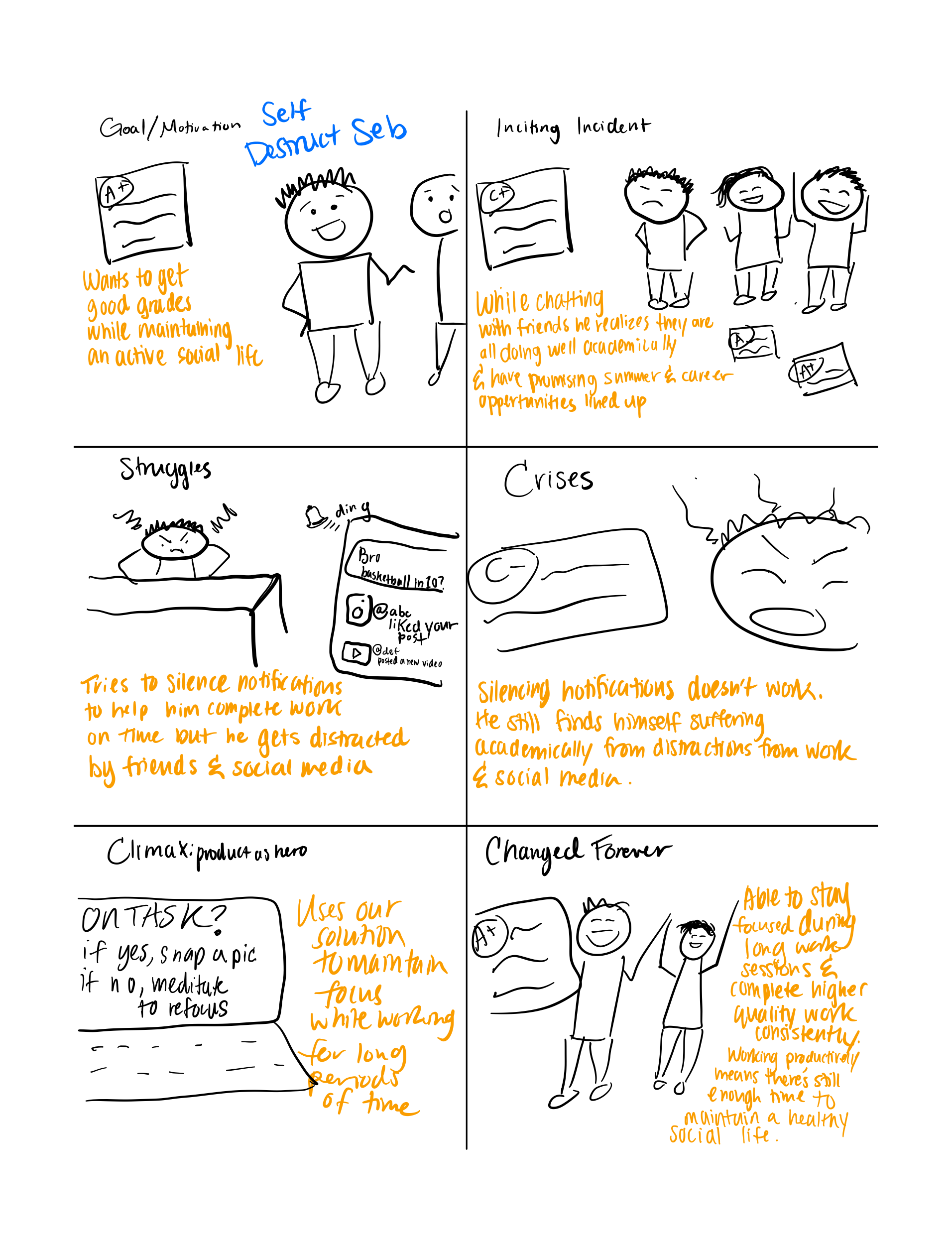

Self-Destruct Seb

Their main goal could, in many cases, be described as to “work hard, play hard” in that they want to be successful, but they also have a higher focus on developing their social experience and connecting with those around them. This type of person enjoys working in groups and is definitely a hard worker, but they consistently find themselves distracted by social forms of communication like texting, social media scrolling, and conversations and events that come up in their life.

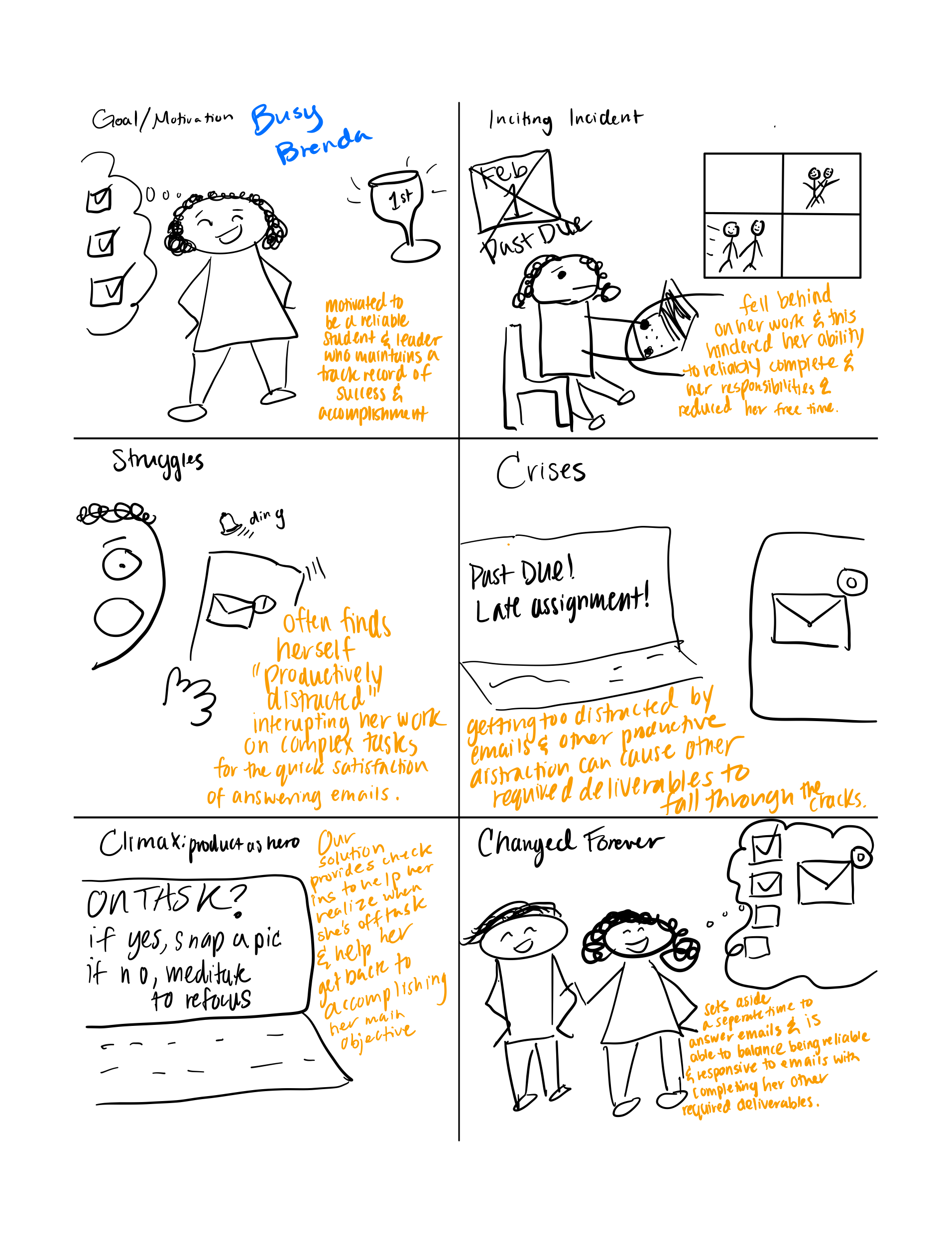

Busy Brenna

Unlike Self-Destruct Seb, they are equally motivated by extracurriculars and a million things in their schedule besides just academics. This is in many ways the classic “club president” student who ALWAYS seems to be running around doing things and just needs more hours in the day. They find themselves distracted sometimes by social communication and activities, but more often simply by other work; small tasks, emails here and there, and etc., which makes it hard for them to hone in and focus on their priorities.

Journey Mapping

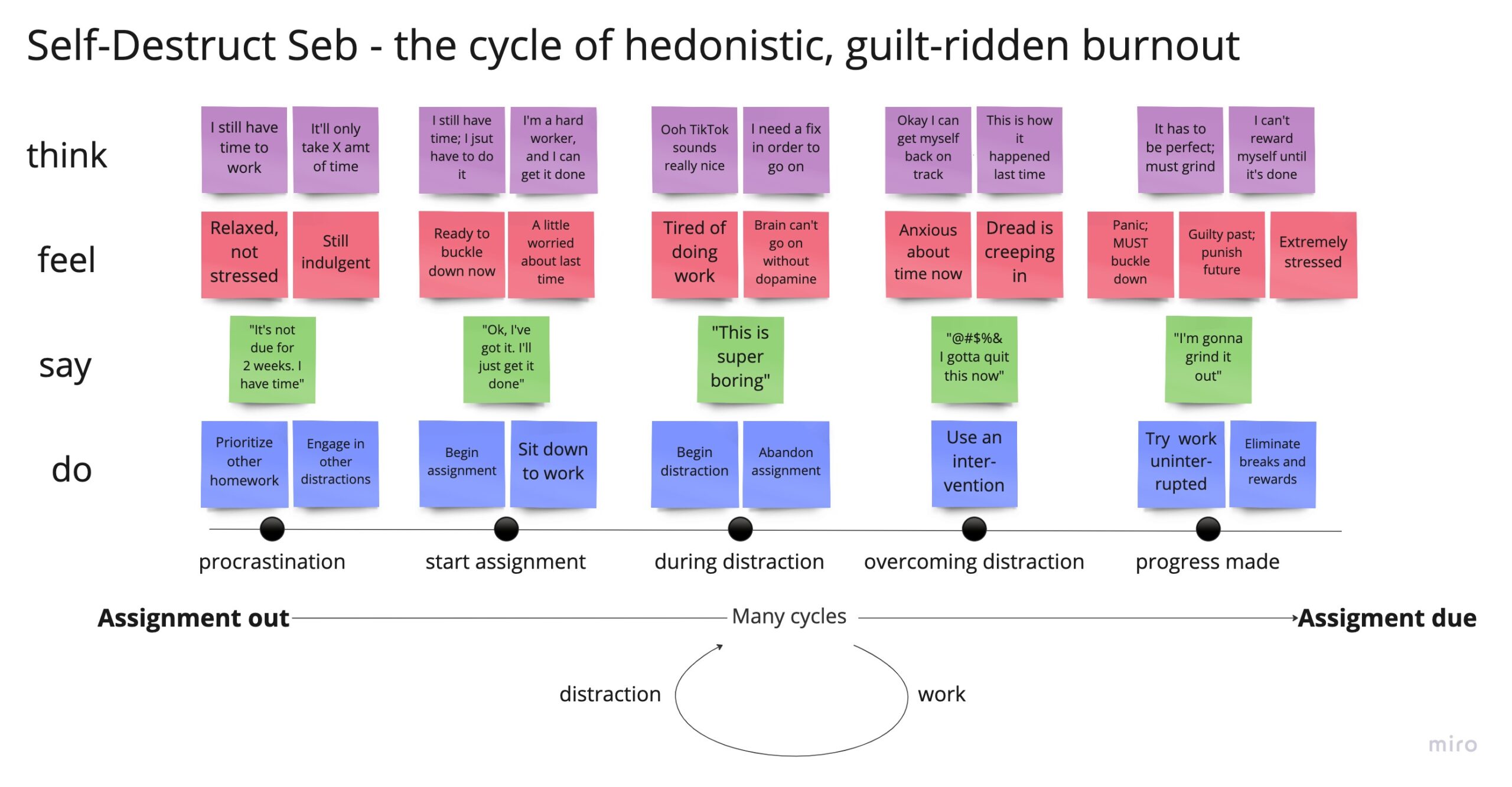

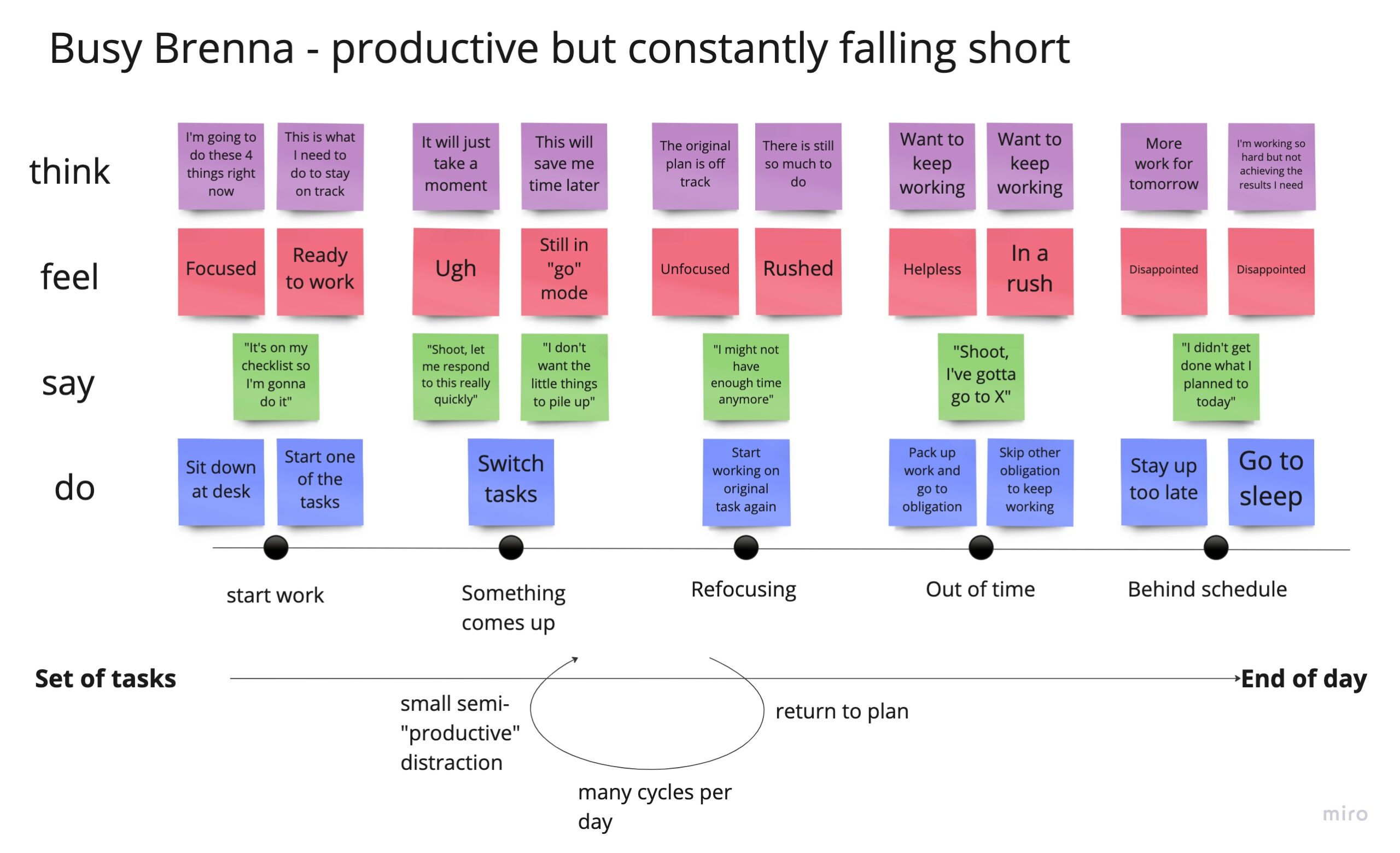

From each of the proto-personas, we generated journey maps to represent a micro-cycle in each multitasking paradigm, and capture what each proto-persona experiences at key time points.

Self-Destruct Seb

People who fall into this category start tasks optimistically, but can be easily distracted by social media or other derailing social engagements. Suddenly, they are off task and find themselves with little progress made. They begin working, often adapting a temporary “grind set” but are easily distracted again. These frequent distractions become frustrating and quickly burn the person out. They can, at times, lead to missed deadlines or work conflicting with social priorities.

Busy Brenna

Our second journey map is labeled “productive but constantly falling short.” They’re motivated by a desire to lead and help others. Often, they’ll sit down to work on tasks but are distracted by emails and other work-related mini-tasks that come in and require their attention. They feel they need to do these small tasks immediately to ensure they’re not “blocking” anyone else from getting their work done and being a good team player, even if that means carrying the team. They may feel like they’re never getting enough work done, leading them to try to do even more work which can be stressful and disappointing.

For more information, read our blog post.

Intervention/Product Ideation

With synthesis, our new paradigm revealed gaps in the market’s assumptions about what users need that preyed on users’ desires for narrow quick-fix solutions, as compared to anecdotal and empirical evidence.

We conducted ideation in three rounds:

- 21 free-listed solutions based on the literature and competitors.

- Selected 7 based on themes identified in the baseline study.

- Top 3 ideas selected based on their pros and cons, and their utility to users.

Idea 1: Meditate during every distraction onset.

The pros included the potential to reduce distractions and promote recovery, and combining it with a time-based scaffolding system could promote sustainable behavior change. The cons included the possibility that meditation could detract from the original task, and the user might ignore the prompts and start a derailing distraction during the wait time.

Idea 2: Accountability virtual buddy-study sessions.

The second solution was to use virtual buddy study sessions for accountability. The pros included positive reinforcement, motivation, collaboration, and peer-to-peer learning. The solution was easy to implement using video conferencing software. The cons included the difficulty of finding a partner, and the possibility that the partner could also be a source of distraction.

Idea 3: BeReal productivity.

The pros included the random timing of the check-ins, which allowed users to get accurate insights into their productivity. The app was quick and easy to use and could be used socially as a way to foster accountability. The cons included the possibility that the app prompts and check-in photos might disrupt people in a flow state, and the prompts could be ignored in favor of a derailing distraction.

The final decision combined the BeReal app with meditation into a simple interface to test both experiences. We selected this method of distraction recovery as both a) an additive mindfulness habit and b) a distraction intervention.

Intervention Study

Study Goals and Hypotheses

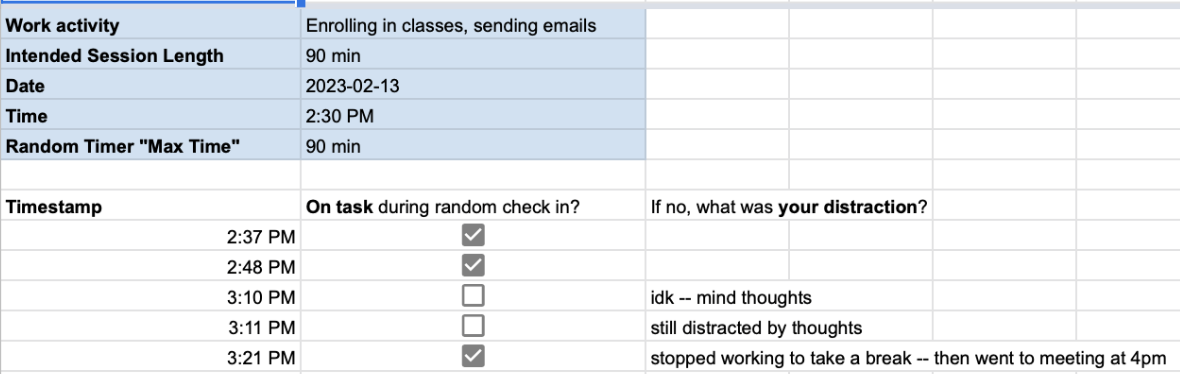

The main aim of our study was to test key assumptions before our final solution: 1. Random check-ins give clear and honest insight into how the users spend their study time, and the system-initiated check-ins could interrupt distractions. 2. Meditation could be a quick and easy way to recover from these distractions.

Methodology

We recruited 8 participants, with 4 new participants and 4 old. Each participant in our study was a current college student who typically works/studies in time blocks. We collected both qualitative (timestamped) and quantitative (daily, pre, and post interviews) data.

Study Procedure

- Set a timer to alert at random intervals.

- When the timer goes off, fill out the above spreadsheet. If on-task, take a “BeReal” photo, and if off-task, meditate for 60 seconds and continue working.

In the spreadsheet, users compiled work activity, intended work session length, date, and time on the spreadsheet.

Learnings and Key Insights

Trend: Meditation is helpful due to a novelty effect, but not universal

Not all our participants enjoyed meditation, but the few who did thought it felt “fresh.” Others skipped it.

Trend: Photos and journalling are cumbersome

Many participants did not take the check-in photos because they were already juggling their tasks. They reported having too much to do already, so a simplification of the check-in process could prove useful.

Tension: Distraction types are highly individual, so solutions must also be

Since participants described being distracted by vastly different stimuli, we reserve skepticism for narrow approaches like app blockers and stand by our scaffolding approach as a way to accommodate for individual needs.

Tension: We targeted the wrong time-scaffolding

Our intervention tried to structure work sessions with system-timed check-ins, but the most common feedback was that the randomness of breaks broke flow states and felt forced. However, when users were caught off-task, the system-timed check-in intercepted derailing distractions. From this learning, we could consider a user-timed check-in, a flipped model of time-scaffolding.

Storyboard and Stories

We synthesized our storyboards for our two personas, Self-Destruct Seb and Busy Brenda. After synthesizing our drawings, we confirmed a previous insight that there are two types of distractions: “pure distractions” (ie Seb uses tik tok) and “off-task but productive distractions” (ie Brenda sends emails).

From the climax portion of the sketch, we learned that our goal is to create a solution that addresses both types of distractions by not only encouraging people to maintain focus but also increasing awareness of distractions and helping people recover from distractions. Our solution plays the role of a nagging mother (checking that you’re on task) and a supportive friend (who encourages you to take mindfulness breaks to refocus).

New Direction

While we’ll officially decide project architecture this week, we have direction. Our behavior change goals have changed since the beginning of the class, from decreasing multitasking by reducing distractions, to recovering from distractions and improving productivity.

Along with that, we expanded on scientific literature, user behavior, and competitor product concepts to create a new paradigm for correcting mistakes in productivity: distraction recovery.

Although a time-scaffolded and mindfulness-forward approach was promising, we then learned from our own intervention study mistakes and discovered that it is crucial to promote a flow state (limit interruptions) and only nudge people when they are actively distracted. Considering our unsuccessful intervention, pivot towards other tools, while standing by a holistic scaffolding approach.

Going into our final product ideation, we ask the following questions:

- Existing solutions can be too passive or too narrow. Ours should still have relatively low activation energy and relatively high intervention strength. (efficacy, viability, user effort) How can we still balance these aspects for users in a sustainable manner?

- Our synthesis and study demonstrated the effectiveness of nudges, provided that the user is genuinely distracted. This is a difficult task for humans to detect, much less AI, and may prove technically difficult. (viability, tech/tools, cost) How can our system provide safety bumpers for users only when they’re off-task?

- Users have different break preferences and distraction types, thus vastly different needs that change even throughout the hour. Personalization is non-negotiable for a successful intervention. (efficacy, viability) How can our system provide scaffolding for this customization? Is it possible across the many devices and tools that users employ during work?

10) Feedback Asks

- What are your thoughts on these final questions?

- Where is potential for gamification, social aspects, and other rewards that we could incorporate?

- Did you encounter missing reasoning between steps, or things we can explore in assumption mapping?