Team 9: Carolina Borbon, Tomy Di Felice, Caroline Gao, Andrea Liao, Annie Ma

Problem Domain:

This quarter, we’re interested in tackling vegetable intake: that is, we’re interested in the successful behavior interventions that lead towards increased / better vegetable intake and attitudes. We’re motivated to study vegetable intake to increase students’ overall physical and mental healths (something our Measuring Me’s revealed we weren’t too good about).

Baseline Study:

Audience: The target audience of our baseline study were students and recent graduates who want to eat more vegetables in their day-to-day lives in order to improve their physical and mental healths. Some obstacles that stood in their way were (1) not having enough time to think about eating healthy, (2) having an aversion to vegetables, and (3) not being able to procure good vegetable dishes due to inconvenience or price. The main way we screened participants (screener linked here) prior to study enrollments were people who have tried to eat healthier in the past, people “kind of” or “not satisfied” with their mental and physical health, and people whose typical meals were 40% or less vegetables. Prior to the baseline study, we interviewed participants to get a better understanding of their current relationship with vegetables (interview questions linked here).

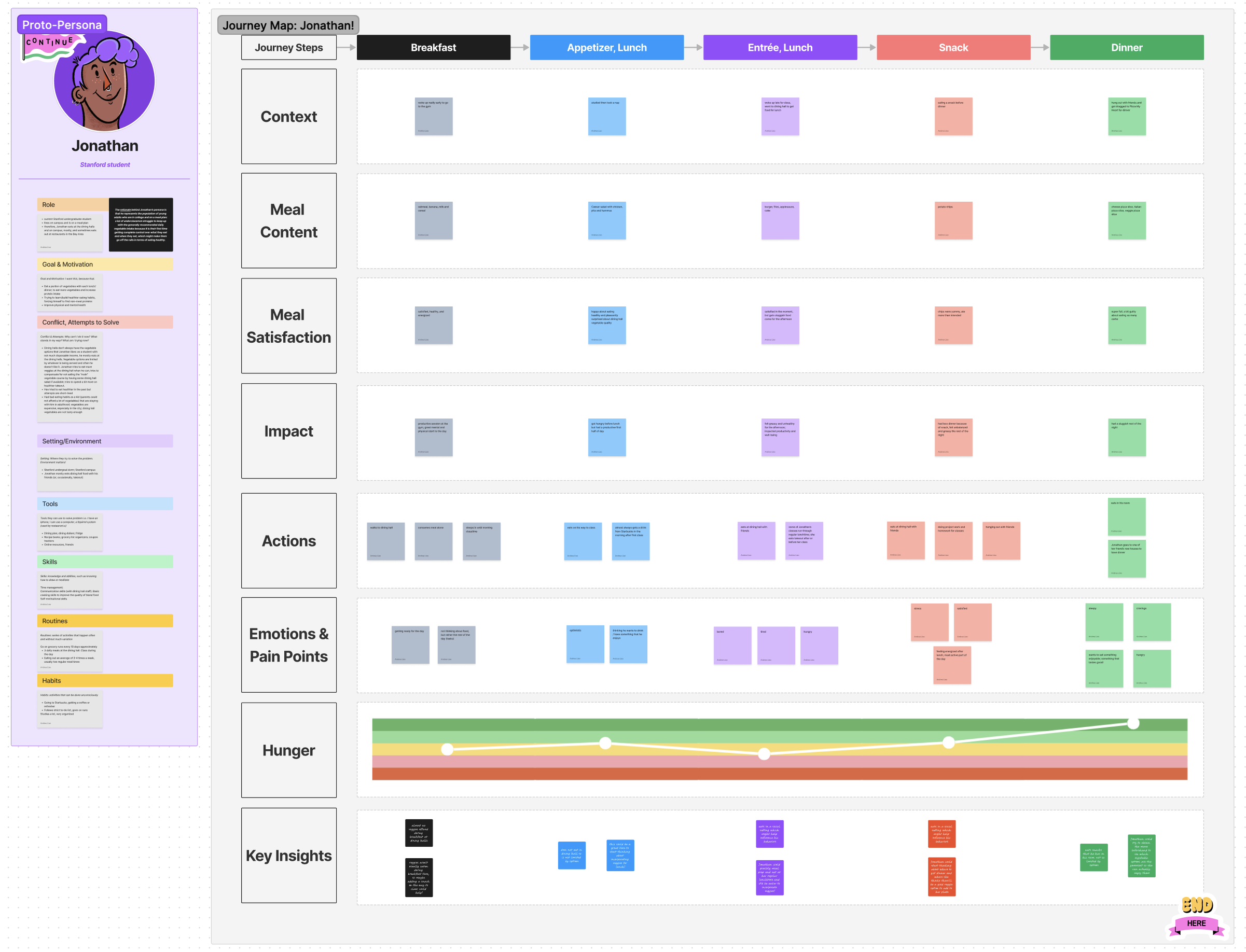

Protocol: For the baseline study, we intended to study how many vegetables participants consume (as a % of the total amount of food consumed) and the various factors that may affect how many vegetables are consumed. Our protocol was to to collect both logistical data (time, location, # people), and content data (hunger level, meal satisfaction, visuals of the actual meal): each participant was sent an empty diary template at the beginning of each day during the week-long diary study and was required to fill out one row / meal or snack. Participants sent over the completed table at the end of each day.

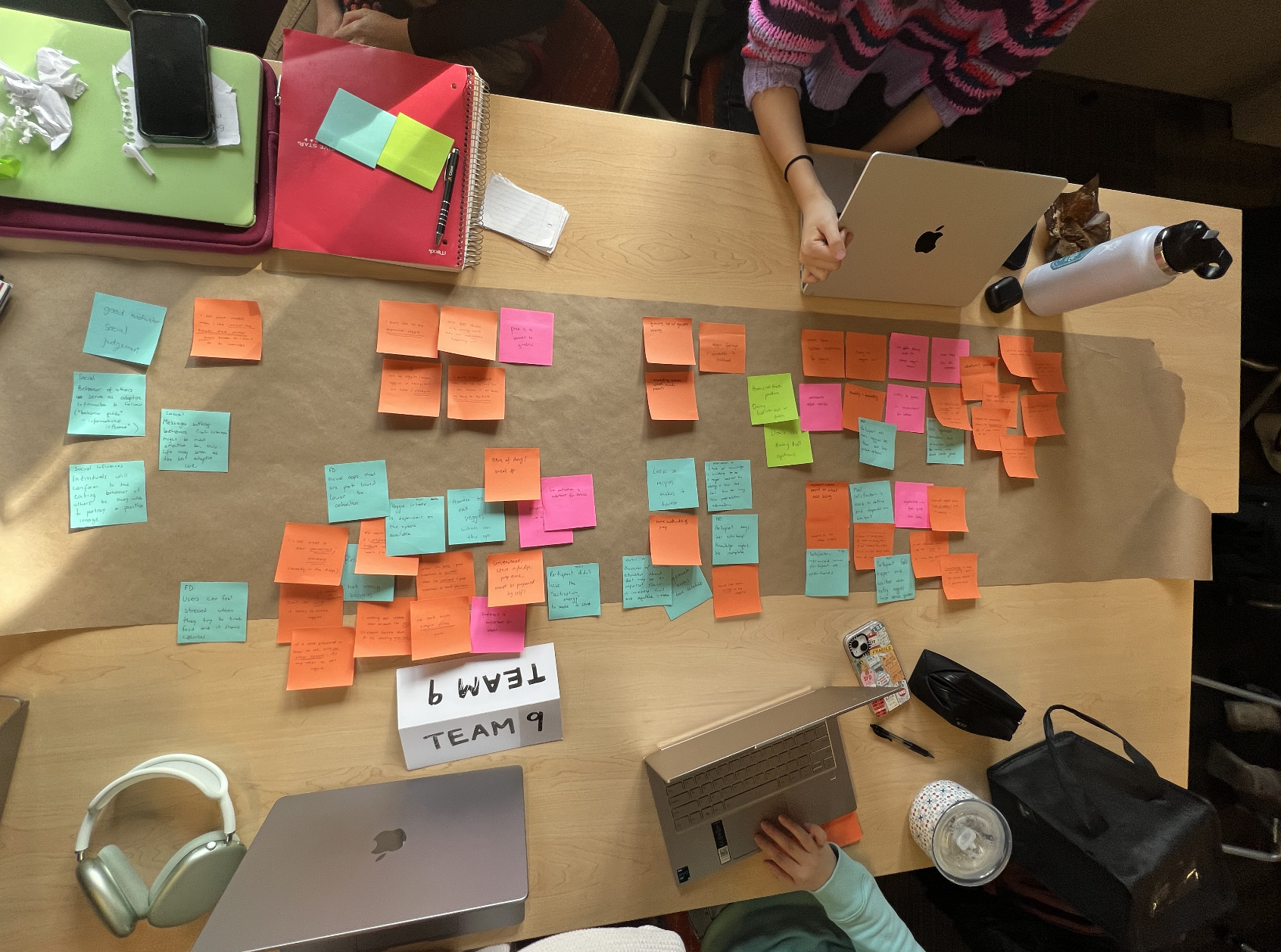

Synthesis: Synthesizing our secondary research and baseline study data (raw data linked here) gave our team a stronger understanding of our various users, what their needs are, what’s working / what’s not, and a plan for intervention. We used a variety of techniques to synthesize our data:

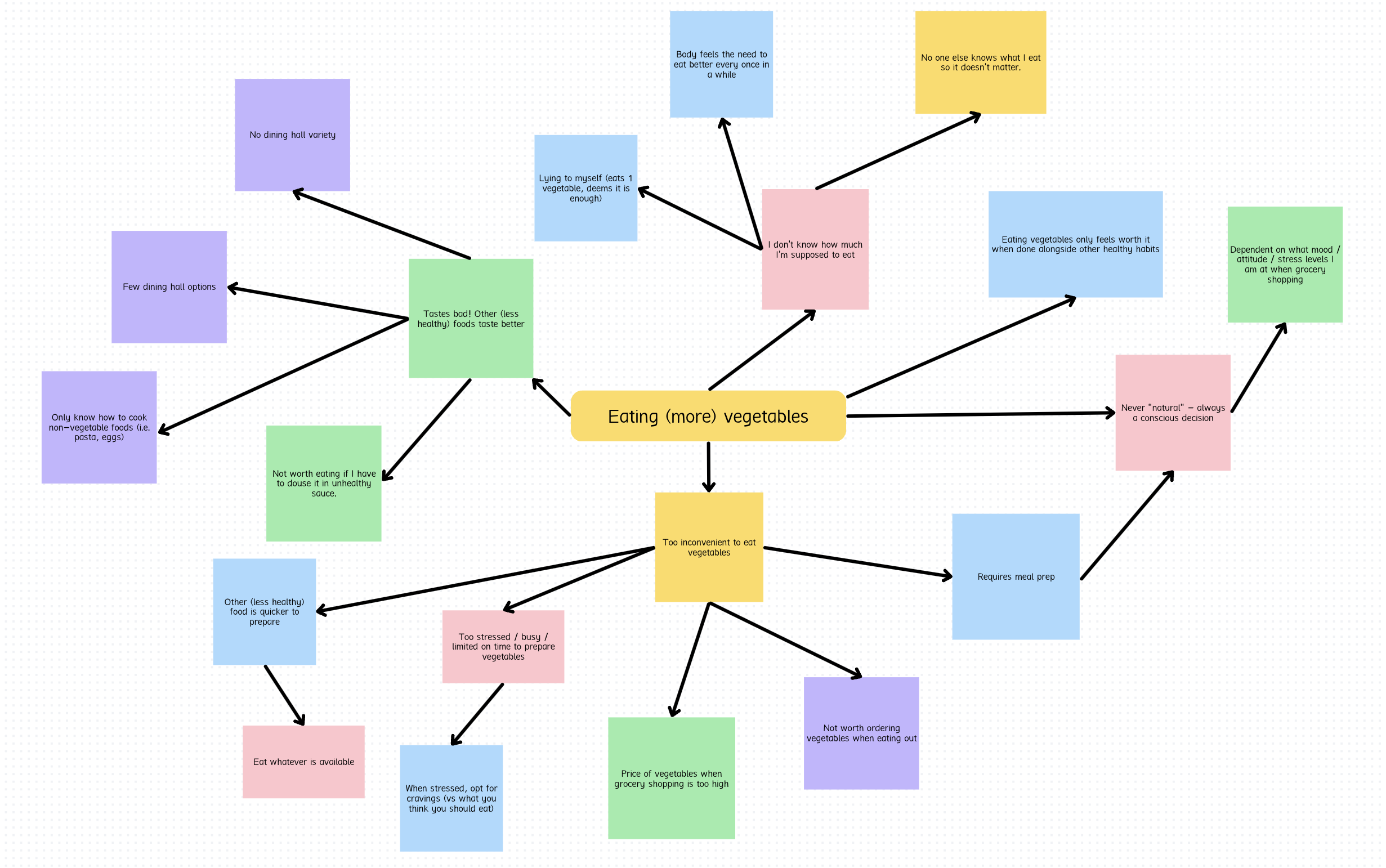

(1) Mind-mapping

(2) Affinity Grouping (Frequency, Timeline)

(3) Connection Circle

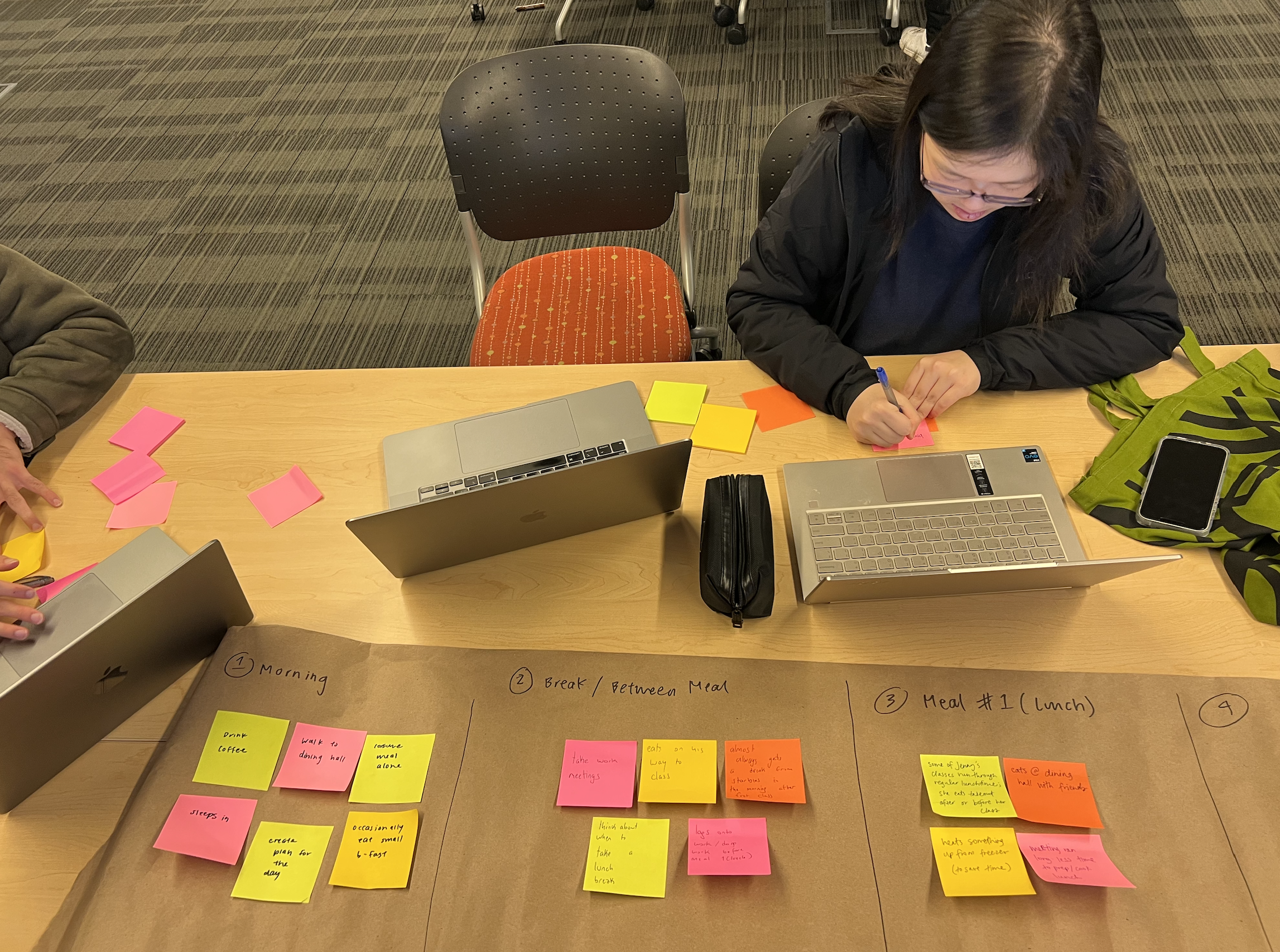

(4) Story Mapping

(5) Fishtail Diagram

Key Insights: Please refer to our 5A blog post (here) for detailed insights from each specific technique / model. Key insights across all 6 mapping techniques / models include:

- Participants receive feedback in various ways – by direct knowledge (knowing they should be eating 2-3 cups of vegetables each day) and by observing others (noticing that friends are consuming more vegetables than they are)

- The six main categories that affect vegetable intake are: convenience, preference, social influence, price, lack of nutritional knowledge, and well-being

- Participants feel there are certain contexts where it isn’t the “right” place or time to consume vegetables – for example, it’s a super busy day so there’s no time to cook vegetables; the only option is to heat available, quick frozen food. Or, after 1-2 meals without eating vegetables, participants felt the need to compensate and eat extra amounts of vegetables. The biggest attitudes / feelings preventing vegetable intake were stress / inconvenience.

Noticeably and consistently, the blockers that participants face when trying to eat more vegetables always feel out of their control(s).

How we moved forward: From the above insights, we decided to get creative to combat convenience (because participants’ day-to-day schedules and situations are, as mentioned, not in designers’ control(s) – if only we had the power to cancel meetings and add 2 hours to everyone’s day to meal prep / cook)! We plan to leverage increasing knowledge about health benefits of consuming vegetables and feedback (via close friends) to convince participants eating vegetables is worth the inconvenience (their bodies already tell them so when they subconsciously or consciously try to compensate).

Comparative Research / Analysis:

Continuing our synthesis, we looked to compare a few different existing solutions in this space (as well as a few solutions outside of this space that we think can inform our approach to vegetable intake). Some of them were picked because of their clear similarity to our project (increasing vegetable intake), while others diverged from this idea but were picked because we thought they had creative, holistic approaches to health that involved food.

We analyzed the strengths and weaknesses of ten different competitors, as well as their target audiences, and what made them unique. Please refer to our 4A blog post (here) for details on each competitor.

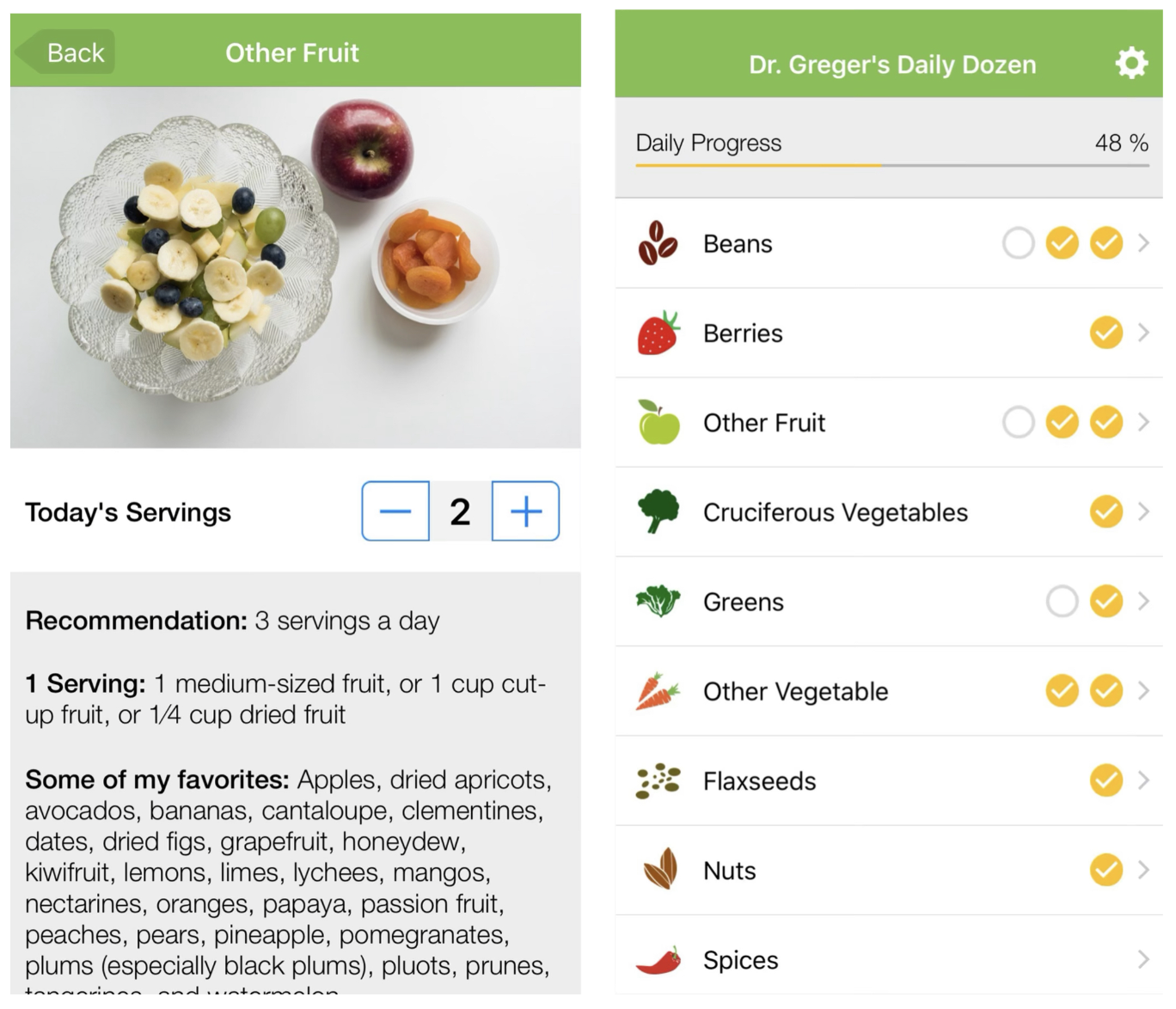

In terms of strengths, some apps were great at creating non-toxic environments to encourage a healthy relationship with vegetables, thus decreasing the activation needed from the user. For example, Dr. Greger’s Daily Dozen did this by suggesting 11 different food groups instead of tracking or limiting calories. This is something we want to keep taking into account given the potential mental health repercussions of tracking.

Some of the greatest weaknesses demonstrated by these apps were the low level of the feedback given. Except for MyFitnessPal, which instantly provides the user with knowledge of the food they are eating, most apps were simply food diaries and lacked a feedback system that would help the user change their habits. We saw this with the Food Diary app which just allowed the user to upload photos of their meals to keep a diary.

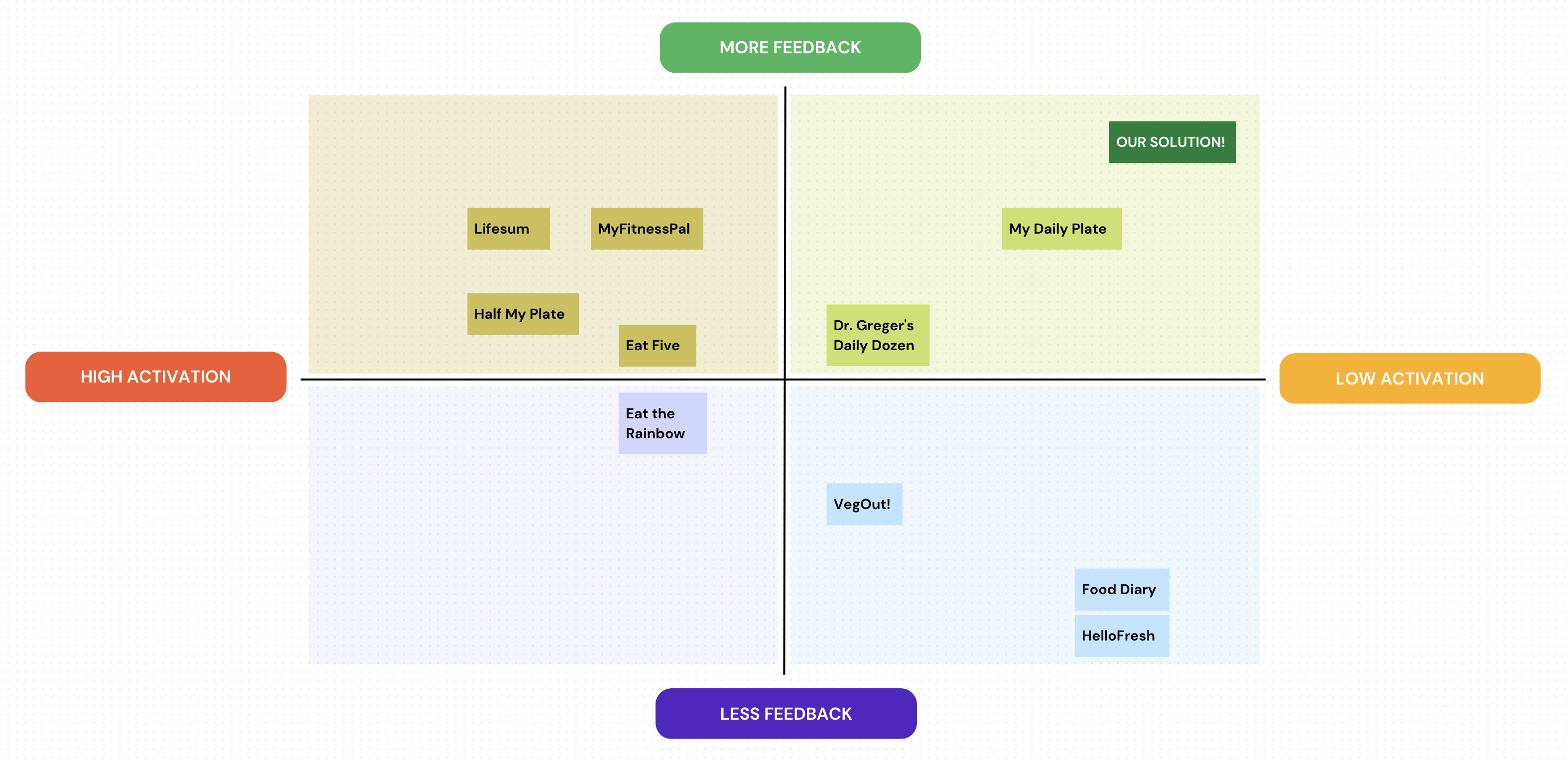

After looking at these various solutions, we mapped them on a comparative matrix where we measured activation (the level of effort users must put into tracking and / or changing their vegetable intake) and feedback (the amount of feedback given by the solution).

Key Insights: We found that solutions that required high activation provided more feedback, and to no surprise, solutions that were low activation provided less feedback.

From this matrix, we’ve found ourselves interested in tackling the open market: developing a solution in the low activation and more feedback space, a solution that makes vegetable intake explicit and natural, and encourages users, via feedback, to build a healthy relationship with eating vegetables. As mentioned above, our product would be distinct by including a socialization aspect to make it more fun, too.

Literature Review:

At this point, we dove deeper into the vegetable intake world with a literature review (for the full review, click here). Our literature review started by looking at how higher nutrition knowledge was associated with healthy eating. To further explore the different factors that influence eating choices, we looked at how finances, childhood experiences, personal motivation, vegetable size and preparation, and social influences all play a role in vegetable intake.

When it comes to financial barriers, we found that the budgetary cost of increasing fruit and vegetable consumption may be a barrier to healthy eating. While there is a need to educate consumers about the importance of increasing their vegetable intake, these nutrition education programs must consider the trade-offs required for families to purchase more fruits and vegetables.

As for childhood vegetable intake, research suggests that repeated exposure can help with an increased vegetable intake for 2 to 5 year-olds. However, it is important to distinguish between repeated exposure and forced eating. A study of young adults found that vegetable intake was shown to be significantly lower when participants had experienced forced eating during childhood. This study of preschool children found that eating vegetables first at a meal was associated with higher vegetable intake. We also took a look at how self-affirmations can have a positive effect on people’s motivation to eat more vegetables.

In regards to vegetable size and preparation, this study shows that the shape and size of carrots, as well as the addition of condiments, can affect eating behavior. Carrots presented in one large cube required the lowest mastication effort and had higher eating rates.

This review found that social context influences eating through identity signaling and self-presentation concerns. It proposes that social factors are influential on nutrition because we see the behavior of others as a ‘behavioral guide.’ Individuals will conform to the eating behavior of others because they wish to portray a positive image of themselves.

Lastly, we looked at this review that examines which subgroups of university students are associated with highest vs. lowest vegetable intake. Being female was the most frequent predictor of higher intake. Other factors identified as influential included living at home, perceived importance of healthy eating, socioeconomic status, breakfast consumption, sleep patterns, nutrition knowledge, activity level, alcohol usage, and energy intake.

Personas & Journey Maps:

Intervention / Product Ideation:

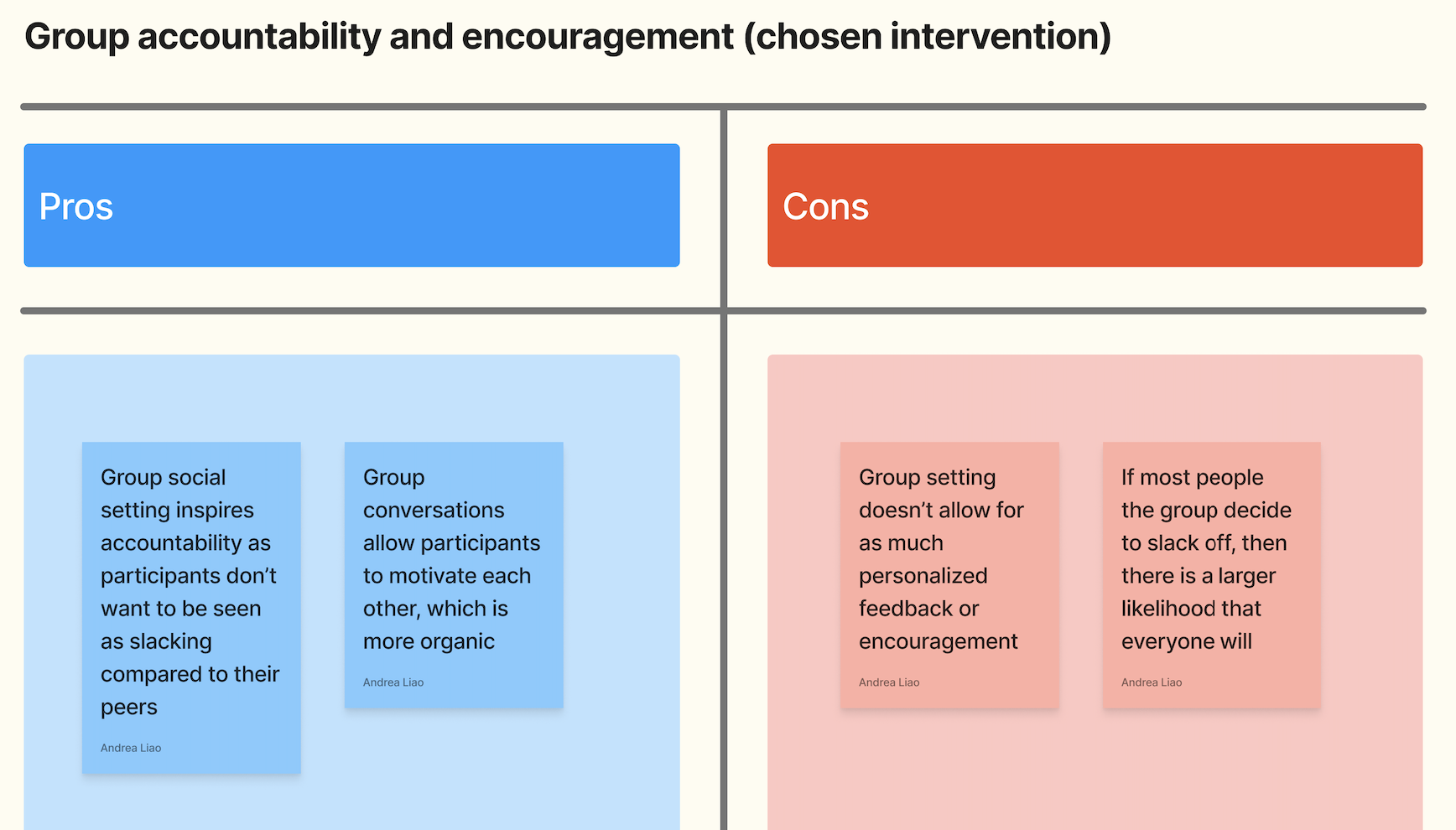

For a detailed description of our three intervention ideas and each of the idea’s pros and cons, click here.

Group accountability and encouragement (chosen intervention): Our chosen intervention idea was to create group chats of two to three participants in each group. We then instructed them to send a photo to the group for every meal. We came to this decision based on observations of our dairy study: participants who felt a sense of comradery with other people on the same journey were more likely to stick to the goal. Additionally, participants noted that just by virtue of having to take a picture of every meal, they were more conscientious about their eating and more likely to want to put vegetables on their plate. Social accountability was a recurring theme during our synthesis process, which is why we included it into our intervention.

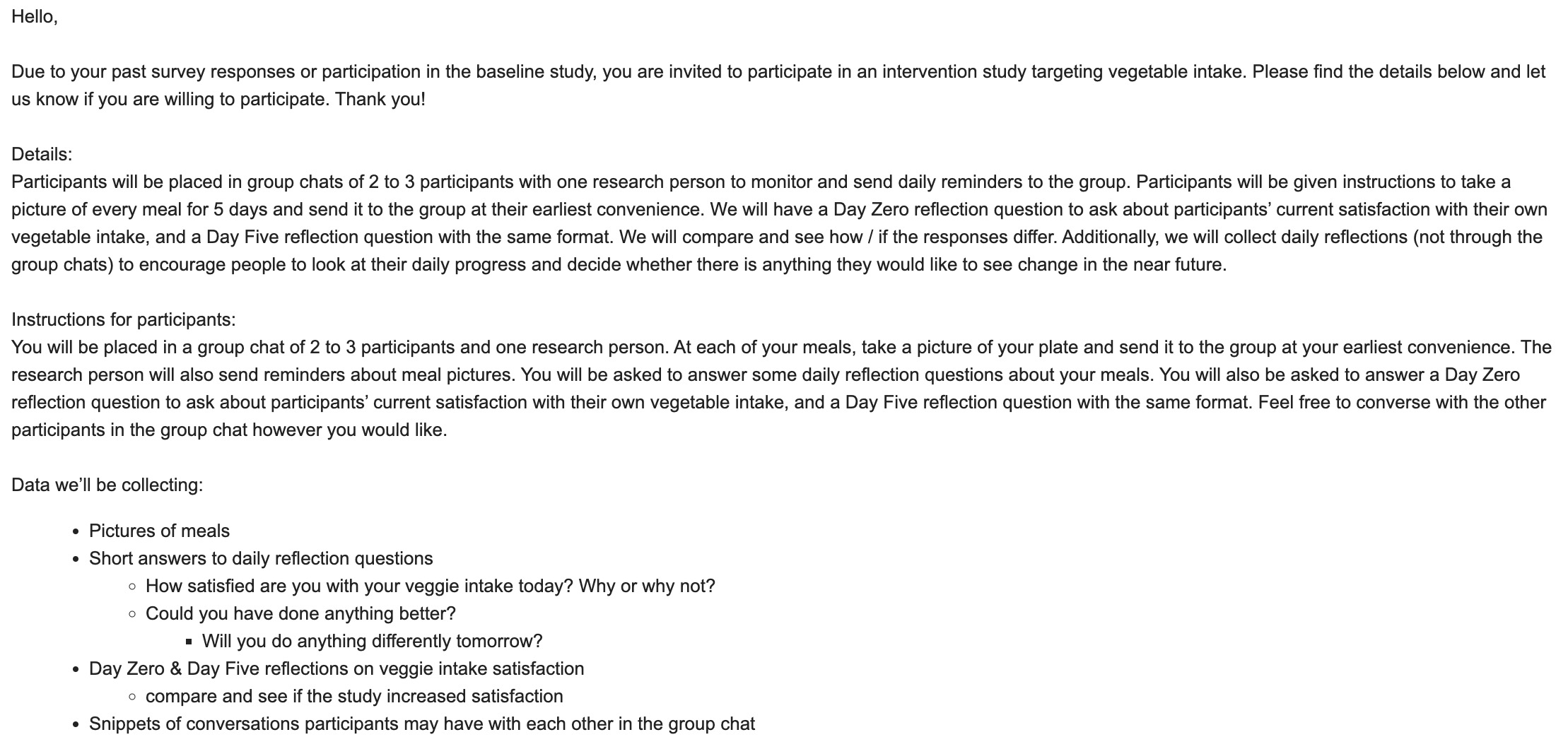

Intervention Study:

Goals:

- Test (and hopefully confirm) hypothesis

- FInd a method that can successfully help target audience increase vegetable intake

Hypothesis: People eat more vegetables if they’re placed in a small group that will encourage them, but also hold them accountable.

Methodology: Number of participants (2-3 per research person)

Target audience: Participants are a mix between old participants (from the baseline study) and new participants who filled out the pre-screener survey but did not take part in the baseline study. General characteristics of our target audience are college students / new graduates who are not satisfied with their current vegetable intake and want to increase it. Participants should have some diversity in demographics, access to vegetables, and lifestyle (how busy they are, how they obtain food, etc.).

Synthesis:

What this means for our project: The insights and trends gathered from the study highlight the potential of group accountability, daily self-reflection, and visual cues to increase vegetable intake and satisfaction with one’s diet. These findings support the implementation of these strategies in the project aimed at increasing people’s vegetable intake. Additionally, the role of group chat conversations in increasing vegetable intake can provide valuable social support and motivation for participants to eat healthier.

However, the tensions and contradictions identified in the study also need to be considered when implementing these strategies. Food waste, comparing one’s own meal with others, and false meal pictures can be potential challenges that need to be addressed. For example, the issue of food waste can be addressed by encouraging participants to plan their meals and take only what they need. The issue of comparing one’s own meal with others can be addressed by emphasizing the importance of individual progress and not comparing oneself to others.

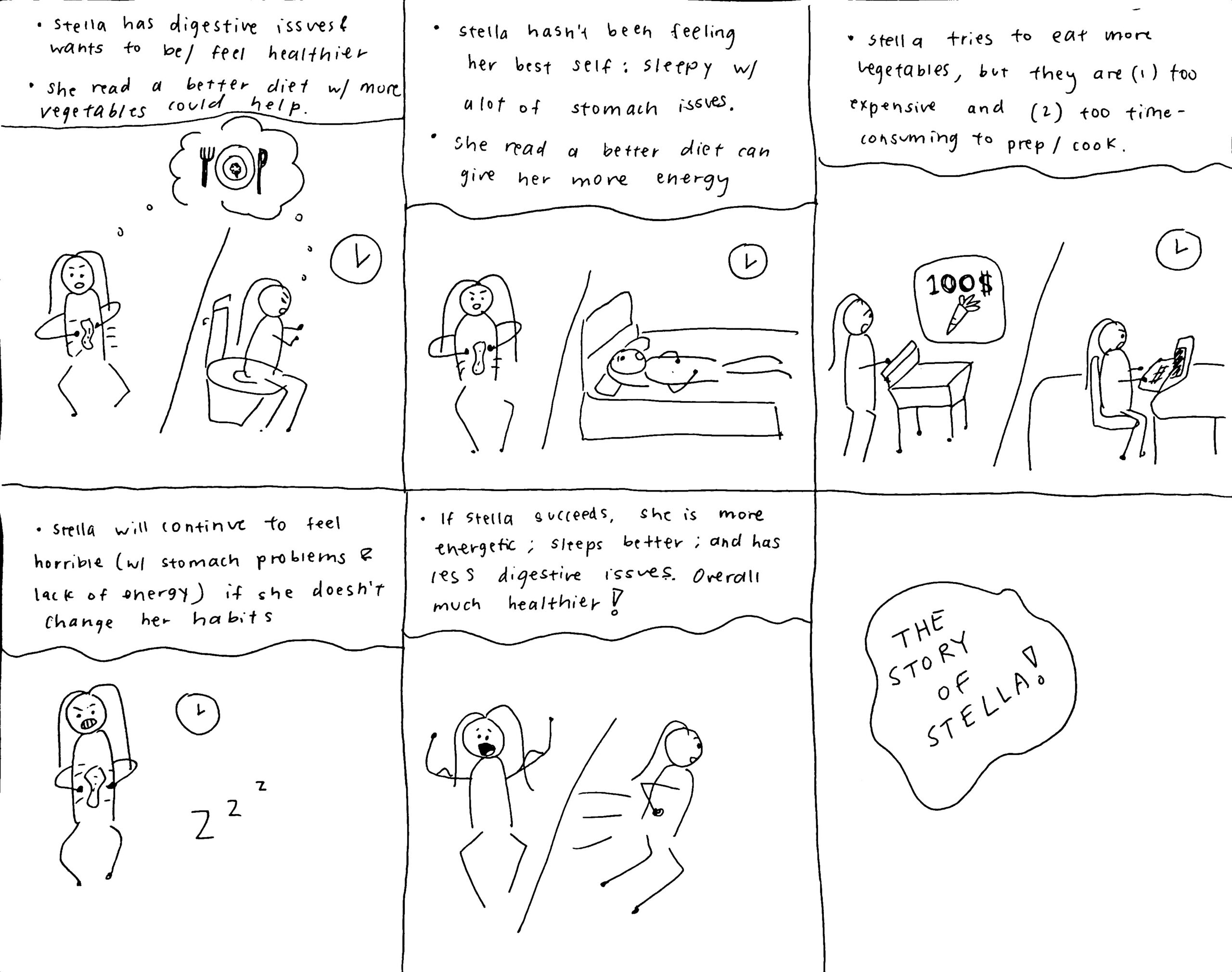

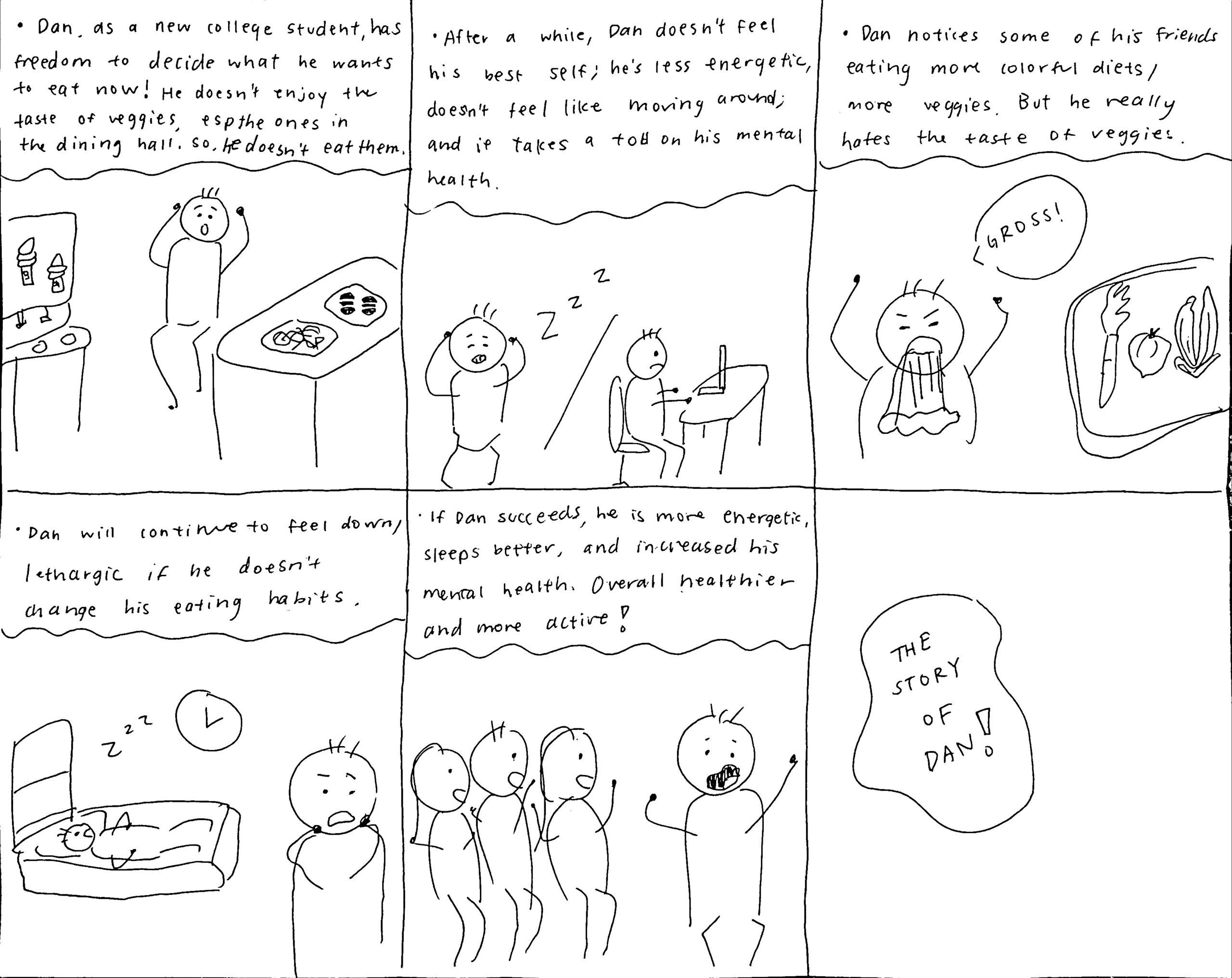

Storyboards:

Our team’s storyboards zooms in on two types of participants: ones who grocery shop / cook for themselves, Stella, and ones who have food provided for them (i.e. eat at a dining hall), Dan. In both storyboards, Stella and Dan want to eat more vegetables to be / feel healthier, either to resolve digestive issues or for better mental health.

Key Insights: From storyboarding, however, we learned that both face inconveniences almost always out of their controls (expensive groceries, demanding work schedules, or bad dining hall options). Instead of fixating on those inconveniences, since they are out of users’ controls, our app tries to convince participants those inconveniences are worth it (via socialization and knowledge). The knowledge aspect will provide users a more direct path to their goal (ex. show users how to make vegetables taste better, or highlight more accessible ways to obtain vegetables).

Future Direction:

The future direction we are taking is a BeReal-inspired intimate group chat with a few close friends that notifies you when it’s time to eat (and snap a picture of what you put on your plate). Backed by key insights from our intervention study, which worked really well, we hope that our app will encourage our users to enjoy eating vegetables by embarking on this shared journey with their best friends! In terms of viability, it is a great way to stay in touch with your friends through a shared love language of food! There are no costs associated with snapping a picture, and it won’t even take up space in the user’s camera roll, as the photos are stored inside the app, similar to BeReal. It requires very little user effort, as it will take a couple of seconds a day, and the only technology required is a smartphone.

Questions / Requested Feedback:

- What are ways to include socialization without impacting mental health / creating toxicity?

- Relatedly, how do we ensure healthy competition?

Word Count: 1993