CS 247B: Design for Behavior Change

Team 15: Mindful Movements

Amantina Rossi, Uma Phatak, Nadia Wan Rosli, Melody Fuentes, Rui Ying

Solution Ideation

We started the ideation process by brainstorming all ideas that may be related to the mindful movement topic onto small sticky notes, based on our synthesis from the baseline study and the intervention study.

Then we affinity grouped similar ones together, synthesizing common themes. An app with smart features such as reminders and snoozing were mentioned a lot; customization also was brought up; last but not least, incorporating progress such as milestones and streaks.

Afterwards, we took some of the key ideas to the bigger paper, stretching preliminary interfaces to fill in more detail. The ideas that were fleshed out include adding timer to encourage completion, showing affirmation languages for progress, etc.

After evaluating ideas together as a team, we made even bigger drawings to showcase the ideal experience/flow of certain concepts for our product. We drew the onboarding (personalization) process, the main screen and how it navigates to and back from other auxiliary screens (such as settings) and even the push notification behaviors.

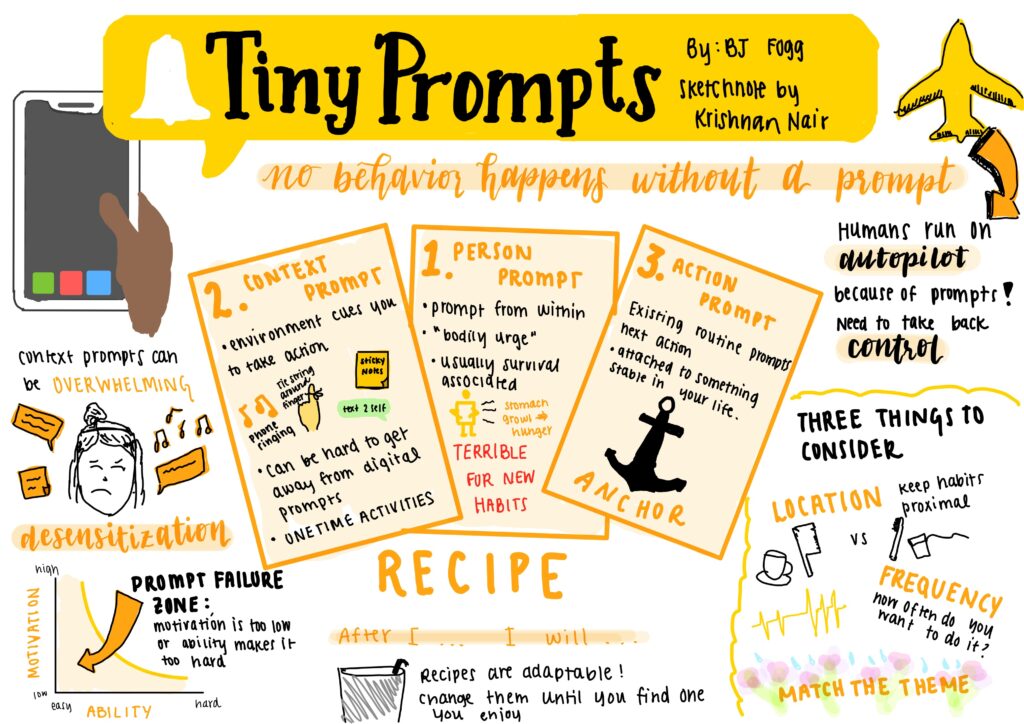

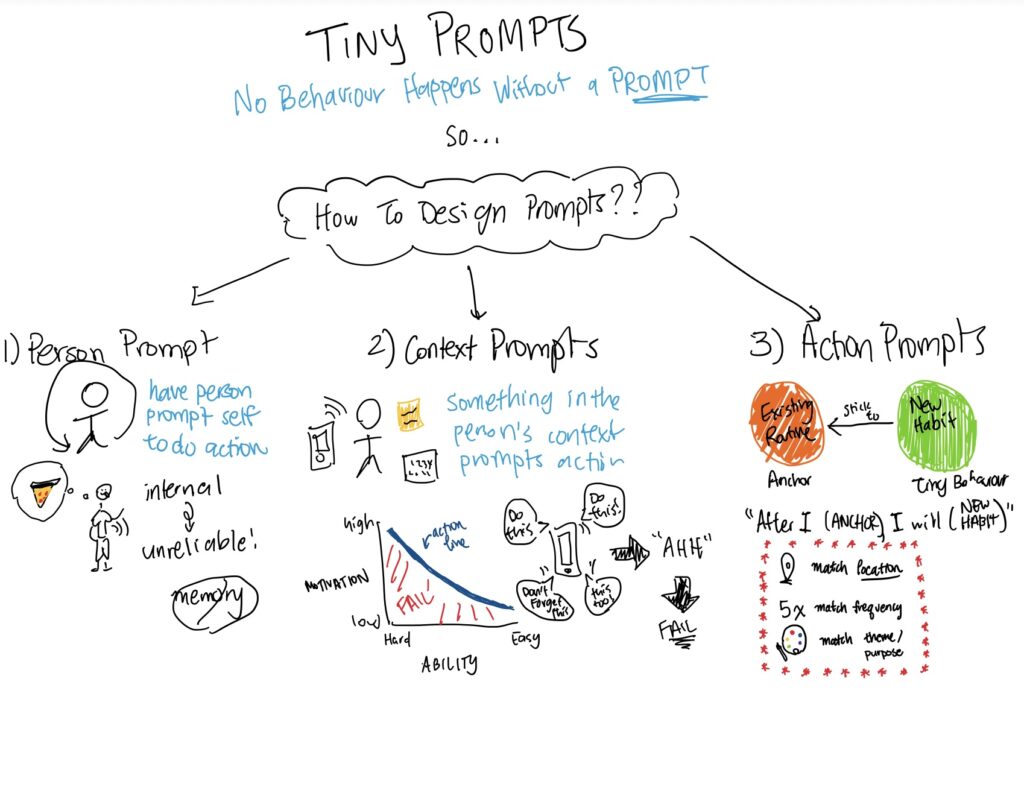

During the solution ideation process, we knew we always wanted to make a reminder-based app to encourage mindful movements, so all the ideas collectively contribute to this solution. The final solution we want to implement is an intelligent app that reminds users of mindful movements at the right time with extra features such as a completion timer and reminder snoozing to better incorporate users’ individual preferences.

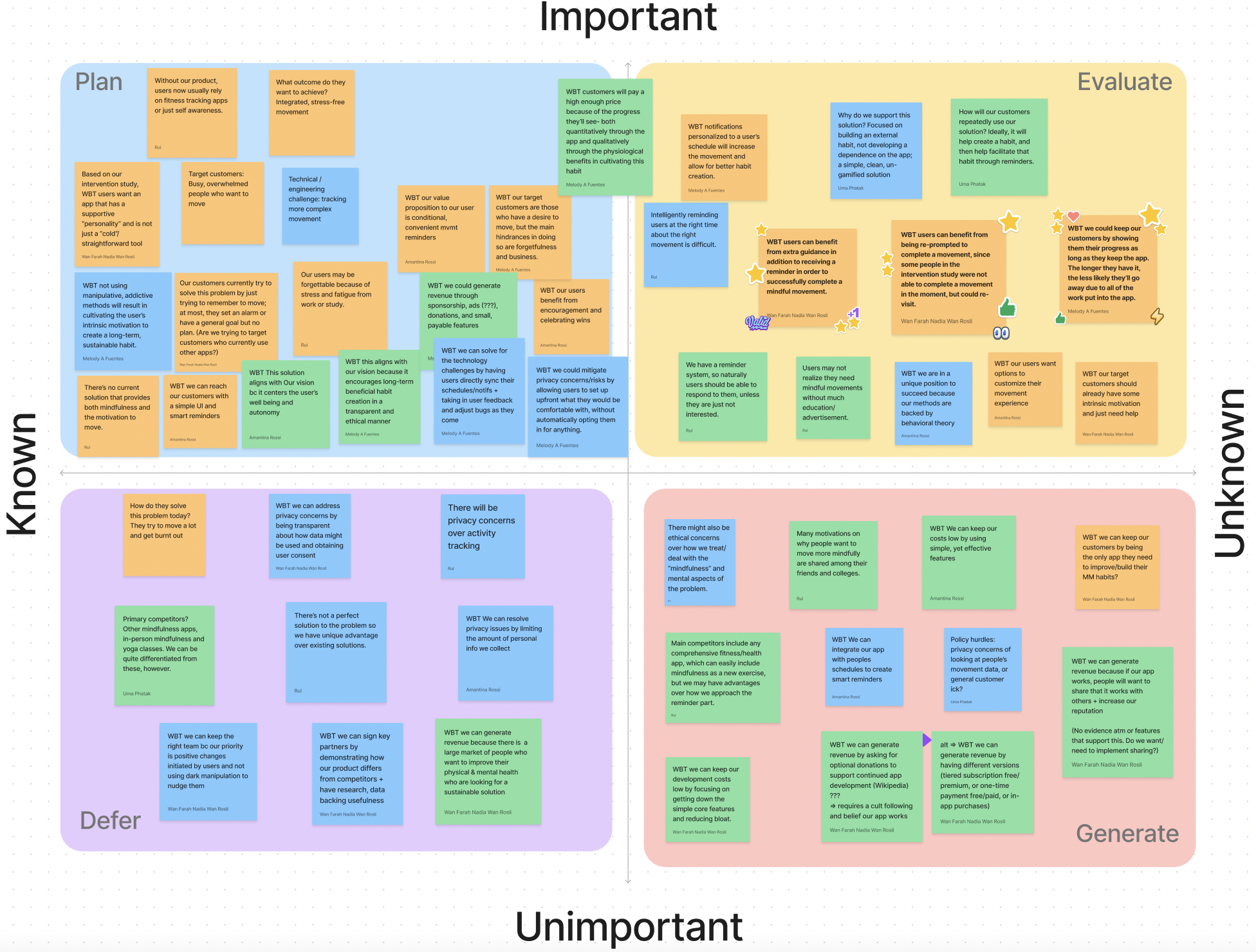

Assumption Mapping

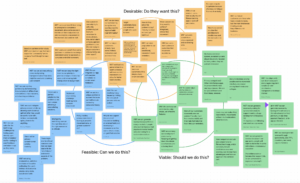

We looked through our solutions and mapped assumptions about the solution related to what is feasible, desirable, and viable and placed those assumptions within three intersected circles.

Then we placed them on a 2×2 matrix with the y-axis being important to unimportant and the x-axis being known to unknown.

The bottom left quadrant of known and unimportant included assumptions that we can defer to later and are not important to test.

The top left quadrant of know and important are assumptions we can use to plan the details of our solution.

The bottom right quadrant with assumptions unimportant and unknown represents the ideas we should generate more ideas around.

The top right quadrant of important and unknown assumptions are those that we should evaluate and find evidence for. You can see that the most important ideas in this quadrant are surrounded by stickers.

We believe the three highlighted assumptions are the most important to our final solution, therefore we plan to test them. We outline the test ideas below.

Assumptions and Experience Prototypes

Here are the most significant assumptions taken from the “important” and “unknown” quadrant from the mapping above. We designed a simple test (experience prototype) for each one of them.

Assumption #1 Progress

Experience Prototype

We believe that: we could keep our users by showing them their progress as long as they keep the app. The longer they have it, the less likely they’ll go away due to all of the work put into the app (sunk cost fallacy).

To verify that, we will: ask people to complete a progressive, easy activity routine that continues for a few minutes. It will get progressively harder, but we will show one group of participants their progress via a visual, and not show the other group.

And measure: people’s desire to complete the activity routine again, in relation to which group they are in.

We are right if: The people who were visually shown their progress are more likely to do the routine again than those who were not.

Assumption #2 Snooze

Experience Prototype

We believe that: users can benefit from being re-prompted to complete a movement if they are not able to complete it immediately the first time they receive a reminder.

To verify that, we will: have two groups of participants – one that receives follow-up reminders and another that does not. We will send all participants an initial reminder to do a mindful movement multiple times at regular intervals in one day regardless of convenience to their schedule; this is so that we can catch them when they are busy as well and cannot immediately complete a mindful movement. We will ask participants to respond if they did the movement after receiving their reminder. For the group of participants receiving follow-up reminders, if they do not respond within 15 minutes, we will send them another reminder every 15 minutes until they respond, up to 3 additional times (4 reminders in one hour).

And measure: the rate of completion of the mindful movement as well as how long it took them after receiving the reminder to do the movement.

We are right if: the group of participants who receive follow-up reminders have a higher rate of completion of mindful movements.

Assumption #3 Timer

Experience Prototype

We believe that: Users can benefit from extra guidance in addition to receiving a reminder in order to successfully complete a mindful movement via a timer.

To verify that, we will: Send participants a 15-30 second timer with a reminder that they would use to guide them through the time it takes to complete a short, mindful movement. If they want to continue after, they are more than welcome to.

And measure: Whether the participants are more likely to act on a mindful movement as a result, along with the amount of time they do the movement for.

We are right if: The proportion of reminders sent versus actions completed goes up, showing that this little push of guidance makes participants more likely to follow through on their habit creation.