https://docs.google.com/document/d/1glRCxnYGKNqD_SxZ3NEJYYcN8VaprQCo5pvADMVHLKo/edit

Part I Synthesis

Section 1 Baseline study -> Raw data -> Grounded Theory

Our group studies students and young professionals’ negative phone usage with the aim of helping them cultivate better phone usage habits. We define “negative phone usage” as the phone usage that individuals want to minimize, which might vary from person to person. As one of the primary sources of information, communication, and entertainment, mobile phone use is in excess. Young adults spend more time on cell phones for social media, playing games, and other entertainments, to the point that phone usage affects many other aspects of their lives, as well as their mental and physical wellbeing. Therefore, it is important to understand what kind of phone usage habits that our target subjects find are negatively impacting their lives, the factors conducive to such negative phone usage, and how we can design tools to help them reduce negative phone usage and increase their phone usage satisfaction.

In our baseline study, we looked into people’s existing phone usage patterns and their attitudes toward different types of phone usage. With our target population being young adults who feel over-reliant on their phone as a daily source of screen time and are unsatisfied thereof, we used a screener that asked people’s main source of daily screen time, how they feel about their daily phone usage, and whether they have tried to reduce their phone usage in the past to recruit people who fall into our target group. From the 17 people who filled out the screener, we selected 8 participants who have a daily phone screen time of over an hour, feel unsatisfied and want to reduce their screen time to enter into our diary study. We conducted a pre-study interview with each of the 8 participants, asking about their current phone usage and how they feel about it, their previous efforts to change their screen habits, their most used apps and the circumstances under which they use these apps, as well as what positive (negative) screen usage means for them.

Then from Jan 22nd to Jan 26th, we ran a 5-day diary study to collect logistical and content data of the participants’ phone usage with the plan of associating quantitative and qualitative, objective and subjective perspectives. We asked the subjects to report their screentime analytics on their phone at the end of each day so we can see: (1) their daily screentime, (2) The distribution of this screentime across different apps, (3) the times at which they use their phone throughout the day. We also asked the subjects to write a short description of how they feel about their screen usage on that day. At the end of the 5 days, we conducted a post-study interview to hear participants’ reflection on their experience of being mindful of their screen time data, and dig in some data that stood out to us. Afterward, we compiled the data across our participants to extract: Average daily screen time, the most commonly used apps, the times at which participants tended to use their phones, and the circumstances under which people use their phones. Based on the data and insights collected from the baseline study, we created an affinity mapping and formed 5 key theories (bolded below) about phone usage habits.

From our baseline study, participants reported that smartphones play both positive and negative roles in their life and which role it plays depends heavily on the types of the apps the individual uses, how the individual perceives a certain app, what they do on the app. On the one hand, people appreciate their phones as a useful tool to help them communicate and unwind. Several participants reported feeling good after calling friends and family and keeping themselves updated on news. On the other hand, phones are also regarded as a source of distraction or stress across participants. Participants reported feeling overwhelmed by the constant notifications on their phones, concerned about spending too much time watching Youtube, and guilty about going down a rabbit hole of doom scrolling on social media. More subtly, even when it is for a similar general purpose, people feel differently about different types of apps / avenues. For example, several participants thought that connecting with friends through phone calls feels more meaningful than connecting by seeing their posts on Instagram. Furthermore, we discovered that apps often bring people a mix of good and bad user experiences. Emily told us that she thinks Instagram is beneficial to keep connected with friends, but finds it unhealthy when she spends unintentionally long sessions within the application. These reflections led us to the first key theory: People view their phone screen time as a positive or negative experience depending on the context of the usage.

Just as people have conflicting attitudes towards certain apps, our participants view notifications as inconvenient and overwhelming, but also necessary. There’s a prevalent fear of missing out (FOMO) concerning one’s online presence, leading individuals to resist turning off notifications entirely for fear of overlooking important updates. Moreover, once a notification is received, there’s an irresistible urge to check it promptly, contributing to frequent pickups throughout the day, a phenomenon often underestimated by users. However, not all notifications hold the same weight, with personal or urgent notifications such as direct messages and messages taking precedence over others. Interestingly, Bob’s case stands out as his pickup behavior didn’t align with his notification count, attributed to the different types of notifications he received, with more importance placed on certain categories like direct messages and news updates.

We also looked into the factors that are conducive to high screen time, a prominent one among which is the convenience and proximity of phones. Participants noted that the absence of their phones for extended periods rendered them less inclined to check, suggesting a correlation between physical distance and reduced screen time. Amar and Bob highlighted how engaging in social activities or being on the move diminished their reliance on their phones, whereas solitude often prompted increased usage. Moreover, the ease of accessing smartphones for brief interactions, as noted by multiple interviewees, facilitated habitual scrolling during idle moments. Another insight revealed a tendency for individuals to unintentionally spiral into prolonged phone usage once they initiated brief checks, as observed in the experiences of Sandy and Amar. Additionally, participants disclosed a preference for using their phones extensively in comfortable environments, such as bed or cozy seating areas, attributing this behavior to the ease of access compared to other devices like laptops. Mandy’s account underscored this notion, emphasizing the allure of smartphone usage in relaxed settings. Allison further exemplified this by describing extended morning phone use while still in bed. These findings elucidate the intricate interplay between environmental comfort, habitual behaviors, and smartphone usage patterns, contributing to our understanding of the factors influencing prolonged screen time.

We also explored how screen time affects other aspects of life and discovered that screen time is inversely proportional to social interaction. Participants emphasized feeling a societal expectation to abstain from phone usage during face-to-face interactions, recognizing the importance of undivided attention in fostering meaningful connections. Amar and Bob highlighted a stark reduction in screen time when engaged in social settings, contrasting with increased usage when they are alone. Furthermore, individuals found relief from the pressure to respond immediately to messages when involved in activities that justified delayed responses, such as sports or academic pursuits. Amar and Eleanor exemplified this by disconnecting from their phones during basketball games or class sessions, respectively. Notably, common high screen time applications like social media were deemed more immediately gratifying than offline activities, leading to instances of skipping classes or neglecting hobbies in favor of digital engagement, as recounted by Mandy and Eleanor.

Interestingly, when looking horizontally across the participants, we realized that different people have varied perceptions in terms of screen time or type of screen usage. Firstly, satisfaction with screen time is closely tied to the progress made in altering one’s usage habits compared to previous days, as evidenced by Mandy’s contentment with a reduced screen time despite still spending a considerable amount. Similarly, Sam expressed a sense of accomplishment on a day with significantly less screen time. Secondly, perceptions of screen time are highly subjective, as observed with Judy, who expressed concern about TikTok usage despite data indicating otherwise, suggesting certain apps may feel more draining, thus influencing perceived usage. Conversely, Sam’s extensive efforts to curb screen time contrasted with the lowest recorded usage among participants, underscoring the individualized nature of screen time perceptions. This made us more aware of the need for personalized interventions and a nuanced understanding of user experiences.

Based on the key theories, we formulated the following questions:

- Theory 1: How can we design user experiences that dynamically adapt to the context of phone screen time usage to enhance positive experiences and minimize negative impacts?

- Theory 2: How might we optimize the delivery and management of notifications such that users can stay informed but not get constantly distracted?

- Theory 3: How can we reduce mindless screen time by adding friction and reducing proximity of phones?

- Theory 4: How can we encourage people to engage in offline social interactions in spite of the immediate gratification of online activities?

- Theory 5: How can we develop personalized tools that accommodate diverse perceptions of screen time and usage types to help users develop habits that fit their positive perception?

Section 2 System Models

Based on our raw data and the grounded theory, we created 4 models, including 2 cluster maps, 1 matrix, and a 2×2, which you can find on this Jamboard. Here we focus on two of them:

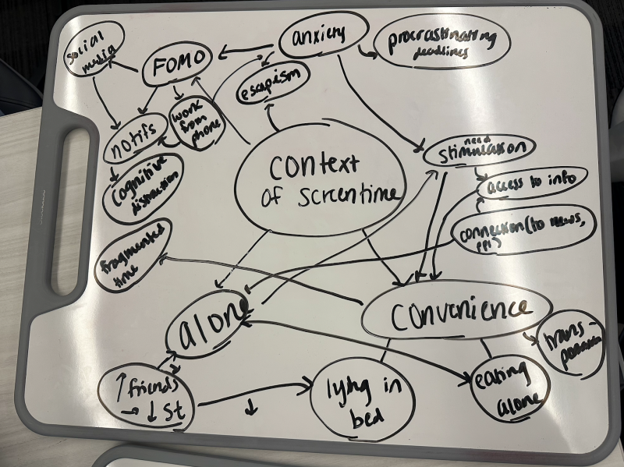

In this cluster map, we explored the contextual and psychological factors conducive to phone usage. These include:

- The fear of missing out (FOMO), which often happens when people either need to work from their phone or don’t want to miss their friends’ life updates on social media. This in turn contributes to notifications being a huge source of distraction.

- Escapism from something that they don’t want to face in real life, which is usually caused by an underlying anxiety or unease about that thing. This anxiety, for example, leads people to procrastinate on deadlines. And one major way that people procrastinate is through doom scrolling.

- Convenience. Phones are a close-at-hand device to access information, to connect with people, to find stimulations, and to kill time. They are also convenient in the sense that compared with offline activities that need venues and scheduling, phone usage has low friction and people can do it so easily anytime anywhere. And this leads to the last factor.

- When people are alone, there’s a higher chance for them to spend more time on their phone, first because of the convenience of phone usage, and second because of the instant gratification that people can acquire from phones, especially when they are bored and alone. This leads to reduced social time, which then reinforces the reliance on phones to alleviate boredom.

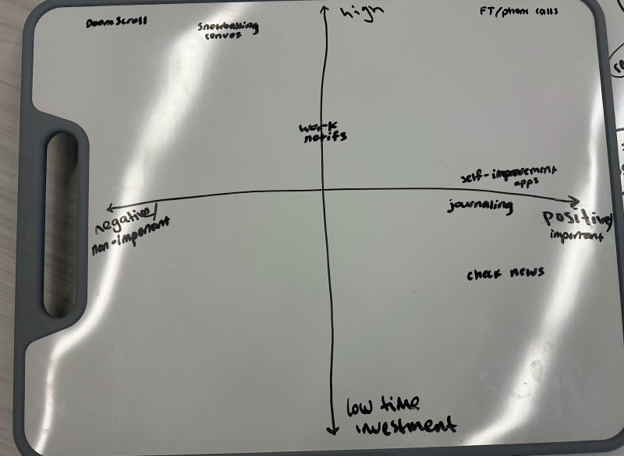

In this matrix, we evaluate the common types of phone usage based on two dimensions: whether they are commonly viewed as positive or negative (important or unimportant), and whether they require a high or low time investment. The matrix allows us to divide the activities into four categories: positive and high time investment (Facetime / phone calls, self-improvement apps like Fitness apps and language learning apps), positive and low time investment (journaling, check news), negative and high time investment (mindless scrolling, snowballing on conversations), and negative and low time investment (which we didn’t think of any). Dealing with work notifications is a neutral activity that requires medium to high time investment. Ideally we want to design tools to help people cut down on phone usages that are negative and have a high time investment and help them either use that time on offline activities or on positive digital activities. We might want to cultivate habits of positive phone usage by starting from the activities that are positive and have a low time investment, and depending on the individual’s own goals, decide whether to include activities that are positive and have a high time investment.

Secondary Research

From our literature review, we looked into several different papers related to our topic, including the effects of pop-up notifications, possible intervention tactics, sentiment analysis of current screen-time apps on the market, and correlations between screen-time and mental health. After consolidating our sources, we reflected on some key findings that guided us during our comparative analysis and subsequent prototyping and journey-mapping. One was that social accountability seems to play a role when it comes to reducing screen-time. That is, being aware of others’ perceptions of your screen-time can influence how accountable you feel when it comes to reducing it. Another finding was that, especially post-COVID, increases in screen-time tend to be related to higher levels of dependency and mental health concerns, especially in youth and adolescents. In addition, when it comes to methods of reducing negative screen-time behaviors, gamification and social accountability seem to have higher rates of success than other methods

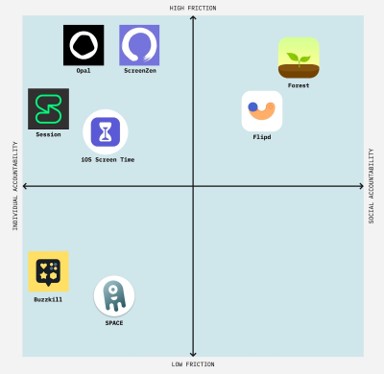

Based on our research, we conducted a comparative analysis of current apps on the market that aim to reduce mobile screen-time usage. In particular, we looked at Forest, SPACE, Session, Buzzkill, ScreenTime (built into iOS settings), Flipd, ScreenZen, and Opal. We tried to diversify the range of apps in relation to the methods that they use to reduce user screentime. These methods included app blockers, notification blockers, gamification, social accountability, pomodoro timers, and customizable notifications. We found that across all apps, there were differing amounts of friction when it came to how easy or hard it was to bypass the app’s restrictions and go back to using your phone freely. There were also differences in the kind of accountability that the different apps offered. That is, some apps focused more heavily on social accountability by allowing you to see your friends’ screen-time or compete with other users, whereas other apps were more focused on individual accountability by allowing you to customize your own screen-time preferences and stick to them. Based on this analysis, we mapped our competitors with individual vs social accountability on the x-axis and low vs high friction on the y-axis.

Based on our competitor analysis, we found that the more effective apps (based on the app store reviews) tended to have higher friction. Individual vs social accountability tended to be more of a preference depending on a particular user, but in general it seems as if social accountability tends to help with retention and engagement. Given these findings, we want our solution to be higher-friction and build in some aspect of social accountability, although the extent to which we implement these features will be based on the results of our intervention study.

Proto-personas

For our proto-personas, we consolidated each of the personas our group made based on the core issues that they faced. Our first persona, Stressed Steve, represents someone who has many priorities and tasks at hand, but finds himself stressed due to doom scrolling. Stressed Steve often picks up his phone while working intending to only take short breaks, but always ends up scrolling for hours on end before realizing how long he’s spent on his phone.

| Drawing | Name | Stressed Steve |

|

Activated Role | Student Doomscroller |

| Goal | Reduce mindless screen time | |

| Motivation | Have more time for more fulfilling activities and build healthier relationship with phone habits | |

| Conflict | Hard to keep track of priorities when scrolling on phone | |

| Attempts to Solve | App time limits, remove apps from home screen (Can only be searched), delete social media, turn on grayscale | |

| Setting/ Environment | On college campus, in their dorm, in bed, in between classes | |

| Tools | Phone, laptop, friends and family to hold them accountable | |

| Skills | Tech-savvy | |

| Routine & Habits |

|

Our second persona, Notification Nancy, is usually able to resist the temptation of doom scrolling itself, but finds herself with a high screen time because she is constantly checking her notifications. Although many of these notifications may be related to work or necessary updates, she will occasionally get lost in a random conversation that could have waited until her work was finished, due to the compelling aspect of notifications.

| Drawing | Name | Notification Nancy |

|---|---|---|

|

Activated Role | Phone user who can’t ignore notifications |

| Goal | Reduce distractions that stem from phone notifications | |

| Motivation | Gets distracted from tasks due to notifications, feels glued to phone throughout the day b/c constantly checking notifications | |

| Conflict | For people with more impatient personality types, it feels hard not to respond to notifications immediately. May also fear that the sender of the messages will feel their lack of immediate response is due to the sender not being important. | |

| Attempts to Solve | Do Not Disturb; notification blocks; app blockers. But usually too easy to undo / can see the notifications anyway, so doesn’t help much | |

| Setting/ Environment | Usually has phone on them, environments where notifications are easy to check | |

| Tools | iPhone, Screen Time, friends/family who can hold them accountable, notification blockers | |

| Skills | Mindfulness | |

| Routines & Habits |

|

Our personas aimed to capture the core issues and sentiments that we gathered during our baseline study analysis. We wanted to capture the different facets of what can contribute to increased negative phone screen-time. These personas framed the ideation and brainstorming that we did for our intervention study. We wanted to find ways to not only tackle the screen-time itself, but some of the motivating factors or influences that underlie negative screen-time usage, such as stress or anxiety. We also realized that what constitutes negative screen-time varies from person to person, and we wanted to be mindful about our intervention not enforcing what counts as negative or positive but rather serving as an avenue for personal reflection and individual mindfulness about one’s own screen-time.

Journey Maps

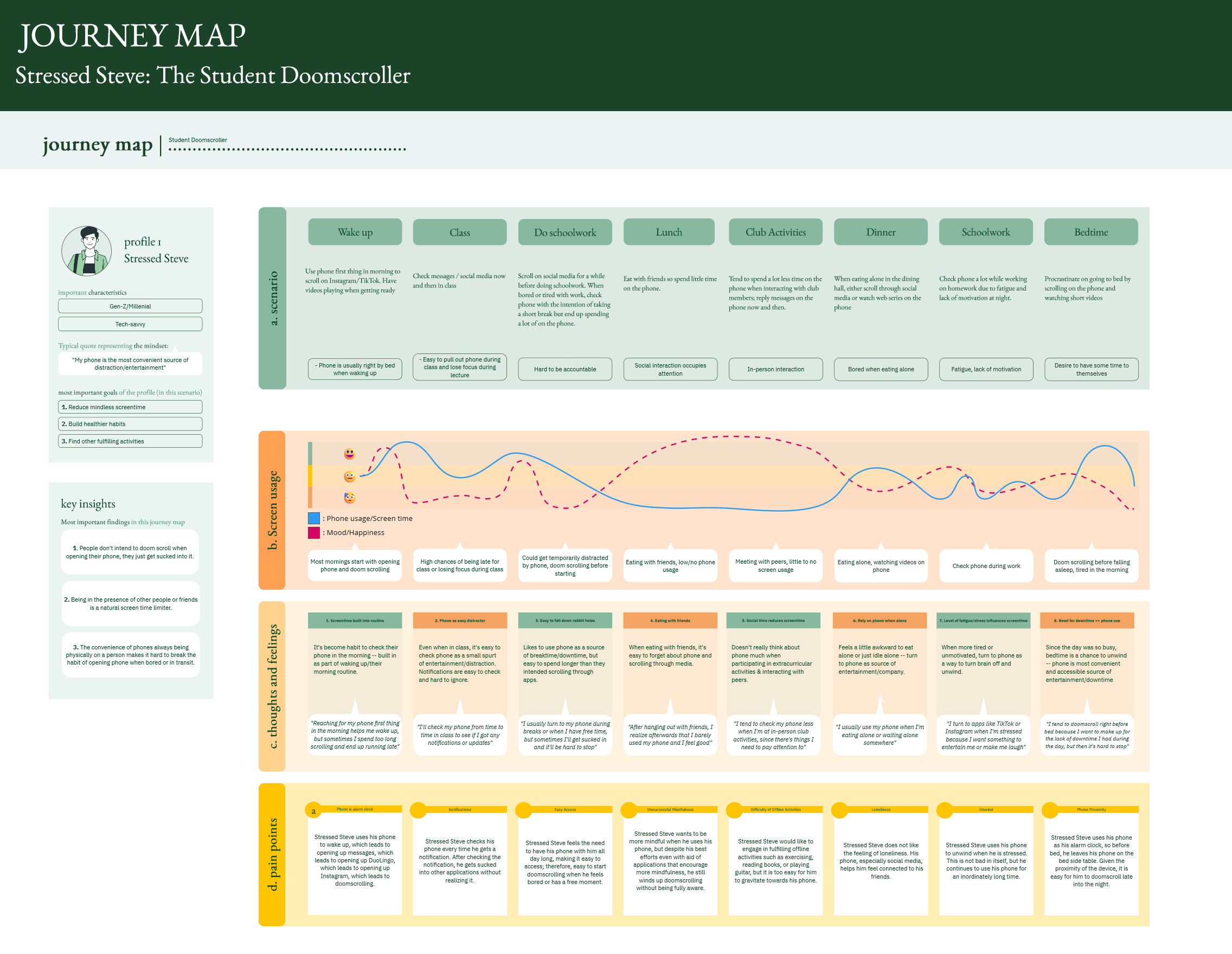

Stressed Steve

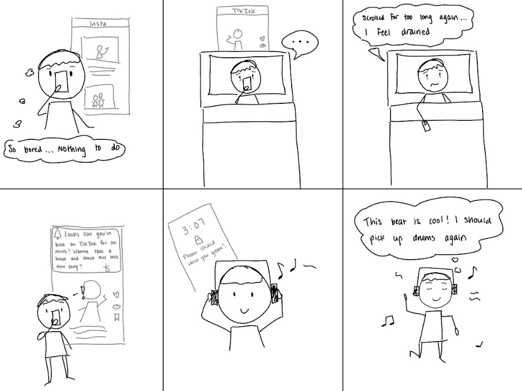

Throughout the day, Stressed Steve is often using his phone in ways he did not intend. He will wake up in the morning with good intentions to check messages and continue his daily DuoLingo streak, but he will end up switching over to applications such as Instagram, then spend undesired amounts of time scrolling through content. When he is using his phone in such a way, it is correlated with a decrease in mood. He feels bad that he is being unproductive. He also feels that he could be doing better things with his time rather than scrolling through mindless content. He would not mind if he only spent a few minutes engaging with friends, but the application hooks him in, and he has trouble getting out until he has the increasing time pressure to get to class or engage in some other activity. In fact, Steve has a tendency to use his phone much less when he is busy. We ideated ideas that make Steve more mindful of the time he is spending in these applications.

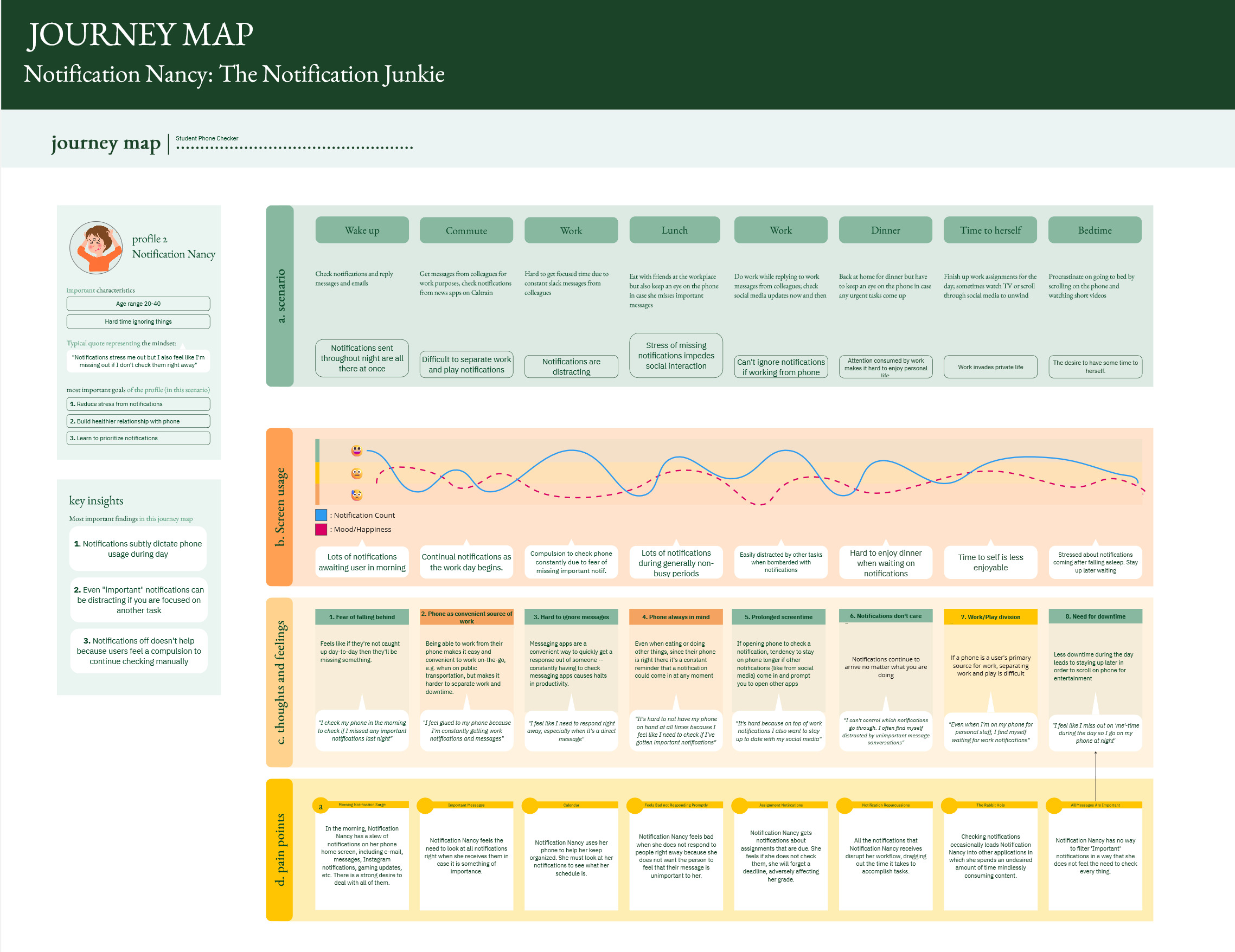

Notification Nancy

Notification Nancy is constantly bombarded by notifications from various applications that get in the way of her productivity, consequently, affecting her mood. She finds that getting hundreds of notifications daily makes it hard for her to stay focused. She gets off track by opening other applications and engaging with content that she feels she does not need to. Her work piles up, making her feel stressed and anxious. She feels the need to always check her notifications in case there is something important that she needs to deal with immediately. In the ideation phase, we used Nancy’s journey map to come up with solutions that help her feel at ease not checking notifications so often.

Click the following link for a clearer resolution of the journey maps

Intervention Ideation/Brainstorm:

To frame our brainstorming session, we used questions centered around simplifying the issue of screen time usage down to its fundamentals. Instead of asking ourselves, “How can we directly reduce screen time” or “What specific apps should we try to remove”, we wanted to get deeper into subtler, possibly environmental, causes of unhappiness related to screen time. This meant exploring questions related to environment and behavior like, “Why do people use their phones/What is the context of screen time for each person,” and “What is the impact of indirect causes such as notifications or physical proximity of one’s phone”. The key point that we considered throughout this brainstorming process was that we didn’t want to be the deciders of what constitutes good and bad screen time. Instead, we wanted to ask questions and design a solution around subtly introducing friction between the user and their screen time. In other words, we wanted to figure out a way to simply give users a moment of clarity before falling into the trap of doom scrolling or unwanted phone use and have them ask themselves, “Is there anything better I could do?” or “Is this the best use of my time right now?”.

With this perspective in mind, we were able to translate our conversation into a design challenge by experimenting with what types of friction may or may not be suitable for our problem. Additionally, using our proto-personas and journey maps, we were able to design not just for an amorphous audience of people, but for 2 specific personas each with their own unique issue related to screen time. For our first proto-persona Stressed Steve, we noticed that his phone usage peaked during times where he felt as though he could take a short break, but bled into more pressing scheduled events such as class or work. So, we were able to construct a series of HMW’s such as:

- HMW help Steve prioritize his tasks?

- Every hour, remind Steve of his task

- Have progress bars so people can visualize task progress

- HMW allow Steve make time for more fulfilling activities?

- Listen to one full song after responding to a notification

- Journal feelings after using phone for too long

- Send an emoji representing mood every time he opens phone

- HMW disrupt the excessive phone-time that Steve has built into his routine?

- Every 5 notifications, text or call a loved one

- If on Instagram more than planned, I’m allowed to change his pfp

- Remind him to drink water / grab a snack

- HMW add more options other than his phone for Steve to entertain himself during free time?

- Give a new song suggestion every hour

- HMW hold Steve accountable for only using his phone for an intended period of time?

For our second persona Notification Nancy, we took a similar approach by starting off with HMW’s before expanding into more specific solutions:

- HMW help Nancy not feel worried about missing important messages?

- Newsletter-type notifications that report important messages at regular intervals instead of in real-time

- HMW help Nancy communicate with her social circle that she only responds to messages at certain times?

- Social app where friends can upload their free time and work time

- HMW help Nancy filter notifications?

- HMW reduce the frequency of notifications?

- Group notifications and use summarization to show theme all at once

- HMW make notifications less disruptive to productivity?

Notable early ideas we had involved physical distance from phones, taking advantage of social accountability, and implementing forced breaks during screen use. We came up with these initial ideas because of a common trend we noticed in our synthesis process where people will often use their phones during brief periods where they are either alone, in transit, or comfortable in bed, and end up being unable to stop using their phone until hours have already passed. Our ideas related to physical distance included extreme examples like freezing one’s phone in ice (In which case a user would have to wait until it melts before being able to access their phone) and more subtle ideas like placing your phone on a far corner of the room before going to bed (Because most of our interviewees mentioned being late to events due to scrolling first thing in the morning). Our ideas related to social accountability were more broad in the sense that we tried to find subtle ways to leverage a community to change behavior related to phone usage. This resulted in ideas revolving around gamification of screen time where users could see a leaderboard of screen usage shared with their friends, or ideas like screen time passwords being set by a friend so a user would have to ask their friend for the password. Similarly, our ideas for forced breaks during phone usage had to do with tracking a user’s current screen time and either locking the phone or removing specific apps temporarily, making it difficult to physically access.

From these initial ideas, we discussed more and realized that one factor we wanted to implement further was an aspect of mindfulness. During our interviews, one of the most surprising yet significant pieces of information we received was that people tend to fall easily into traps like doom scrolling and online shopping and have difficulty stopping in the middle, but if some friction is introduced before the activity is even started, people have no issues with being off their phones. Examples of this include social activities like sports or hanging out with friends, where users tend to not even think about their phones when they are surrounded by other people. Additionally, even when users are alone, we were able to gather from our interviewees that even small reminders like Tik Tok’s personal “Do something IRL” videos or “You’ve been scrolling too long” messages from content creators can lead them to introspect and get off their phones.

In the final stages of our brainstorming process, we were able to combine all the concepts we had been discussing and consolidate them into a number of ideas. The top 3 that emerged were:

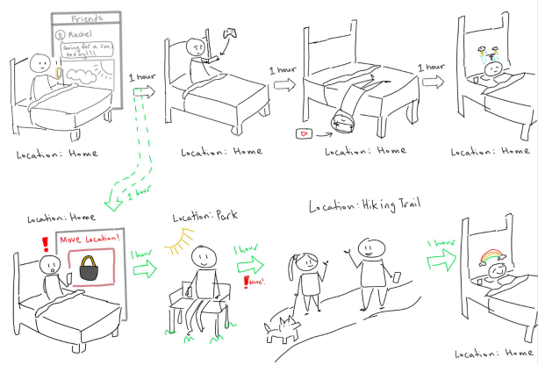

1. A feature that alerts a user when they have been using their phone in the same location for n hour(s) and locks the user’s phone until they move to a new location

2. A feature that displays a pair of eyes on the screen if phone usage is too high and changes expression based on what the user is doing

3. A feature that gives a user new tasks or activities to do (Checking out new music, etc.) when the user is using their phone for prolonged periods of time

The first idea was meant to help a wide range of users as it introduced a physical change of environment. The conflict we attempted to solve with this solution was that when people use their phone for hours at a time, they don’t realize how long they have been using their phone, especially if they are just lounging out on their bed or couch at the end of the day. However, with just a bit of physical movement, the momentum behind using the phone falters and allows the user a chance to do something else. The motivation behind this idea was that the user could still use their phone as the feature doesn’t outright block usage of the phone once they move, but the time taken to travel would give them a moment of reflection and mindfulness. In an ideal scenario, they might run into someone they know or even strike up a conversation with someone new. Some downsides to this idea include the fact that people who work on their device would find it counterproductive, it is hard to incorporate self-accountability into the design, and some people may not want their location tracked by the app.

The second idea is one of our dark horse ideas in which a user is constantly being watched by their device. This idea has a simpler fundamental concept which revolves around the fact that people tend to use their phones less in social settings. We took this aspect to its extreme to try to make the user feel pressured about using their phone for a long period of time. This idea’s main goal was to address the accountability issue of many existing screen time apps. For example, iOS’s built-in screen time function or other third-party lifestyle apps allow users to lock their phones after a set period of time, but it is easily circumvented by the user just typing in a short passcode. With this idea, the user no longer is fully self-accountable and instead has this “figure” introduced that acts as an outside pressure. Some downsides about this idea is that it could feel uncomfortable for users to feel eyes constantly watching them and it has no further functionality other than the eyes.

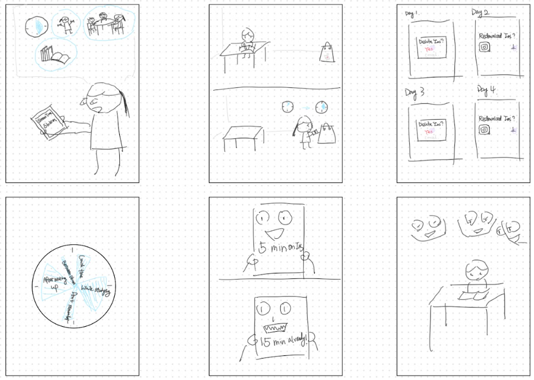

The last idea we came up with is a feature that automatically gives suggestions for activities to do if the user is on their phone for a long time. This idea is similar to the first idea, but is unique in that instead of forcing the user to move locations, it instead proposes fun activities that the user indicates that they want to do. For example, if a user indicates that they want to exercise or listen to new music, the app might give a notification after the user has been on social media for an hour and say “Try checking out this new song” or “The weather is perfect for a short run!”. With this feature, we wanted to reignite motivation for users who may just need a gentle push to get off their phone and do other activities. Additionally, this doesn’t have to be just online vs. offline, if the user indicates wanting to have more positive screen time. In this scenario, the feature might tell the user to switch over to a reading app or one for developing soft skills like Duolingo. Some downsides for this idea is that if there is not enough initial motivation given by the feature, the user may just revert to scrolling immediately, and it has the same issue of being difficult to hold self-accountability.

For the final idea that we decided to pursue for the intervention study, we decided to incorporate the most important aspects of each that we found. Namely, mindfulness and individual reflection regarding phone usage and redirection as opposed to direct intervention. Thus, for now, we have focused on an idea that is similar to ideas (1) and (3) listed above. While we have not yet completely decided on a final solution, we hope to use the intervention study to gauge responses and see the effect of subtle distractions.

Intervention Study:

Goal:

For our intervention study, we are going to introduce reflection and redirection by implementing a system of daily check-ins and questions. We are mainly focused on our persona Stressed Steve who finds himself starting his “phone breaks” with the initial intention of only using it for a short time, but ending up scrolling for hours. As an intervention in this scenario, we will introduce some subtle friction between the user and the phone.

Participants:

In order to better use our existing data, we will be using mostly the same participants as our baseline study. This means that our participant pool consists of a diverse group of people with a wide range of ages from teenagers to graduates. Since phone usage is an issue that isn’t solely centered around one specific demographic, we found it important that we found people who aligned with our proto-personas and could relate to the issue of doom scrolling or getting lost in phone usage.

Set up:

Each day, we plan to check-in with our participants at 2pm and 7pm to encourage mindfulness regarding their screen-time. For our first check-in at 2pm, we will message them saying “Hey! I’m checking in on you – ” and ask the following questions:

- What are you looking forward to today?

- What’s the best use of your phone so far? What’s the worst?

Then, at 7pm, we will say, “Checking in again!” and ask these questions:

- What was the best use of your phone today? What was the worst?

Finally, at the end of the 5-day period, we will ask the users to send a screenshot of their screen time for the past five days.

The times we decided to check-in on are deliberately chosen by our team. As the normal day for most people is from 9am – 5pm, we wanted the first check-in at 2pm, after the user has gone through their morning routine and lunch routine. The purpose of this check-in is to simply give users a chance to take a moment and reflect on their current phone usage, and think a little about how their usage for the rest of the day might look. We are hoping that by doing this at the “start of the end” of their day, it can positively affect their usage between the transition from work to play. The check-in at 7pm is meant to be another subtle nudge for the user to think about their phone usage and reflect on how they’ve used it during the day, especially after work hours. By using this 2 check-in system, we hope that we can see results where the user is positively affected by these less intrusive nudges. In other words, we want to see the extent of the effect of occasional un-intrusive nudges as opposed to direct blocking of phone usage, which we believe is unhelpful.

Data collected:

The data we will collect will be the correlation between what they say at the first check-in with the second check-in, and how their screen time relates to what they say. Since this intervention is occurring with our members directly texting the participants, we hope to also include an added aspect of social accountability, which is also something we are actively keeping in mind. In other words, since the users know there is a person on the other end of the screen, they may reflect deeper and be more mindful about what they are thinking rather than if we had just asked them to take quick notes on their phone.

Questions addressed by study:

We decided not to do a check-in right at morning/wake-up times because we mainly want to see the process of “Reflect on how I’ve been using my phone” to a positive change rather than starting with “Plan how I’ll use my phone for the whole day”. This is because expecting a user to accurately plan their phone usage for the entire day seems unreasonable and too difficult to take accountability for, while scheduled reflections and mindfulness throughout the day can allow for easier and more visible changes since the user knows exactly what to change or not change, based on the reflection.

Comments