CS 247B: Design for Behavior Change

Team 15: Mindful Movements

Amantina Rossi, Uma Phatak, Nadia Wan Rosli, Melody Fuentes, Rui Ying

Synthesis, Proto-Personas, Journey Maps, and Intervention Ideas

To better understand people’s behavior on mindful movements, we conducted a week-long baseline study with comprehensive pre-study and post-study interviews. Combined with related literature review and comparative market research, we synthesized the data, built models around it, and came up with three major proto-personas and their journey maps. Based on these findings, we brainstormed and chose the “smart reminder” as our intervention idea of encouraging people to move more and mindfully.

Synthesis

We wrote down what our participants said, thought and felt, as well as the key insights from literature review and comparative research, onto post-it notes. We then used various mapping techniques to identify themes: trends, contradictions and tensions. Furthermore, we built models to have a clear picture of the user’s needs and obstacles, so we could identify the key moments and scenarios in which we might be able to intervene and make them move more.

Chunking and Mapping

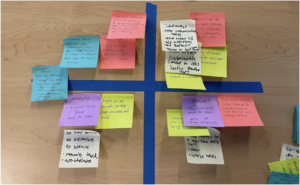

Affinity Chunking

We started with affinity chunking, grouping post-it notes into groups based on their similarities.

We found that in general, the notes fall into four categories:

- Environments: physically, being close to a gym room or inside a room with space to stretch makes people move more; socially, many mentioned that being in a space where people often pass by makes them want to strike conversations, which makes them stand up and move around.

- Effects: many think mindful movements bring positive benefits, but others aren’t sure about if mindful movements can make an obvious difference.

- Awareness: during the study participants were asked to log down their mindful movements. Many realized they had a fairly consistent routine throughout the day and the logging made them more conscious about their decisions on spending time moving.

- Motivations: this category is similar to effects, but focuses more on participants’ own active willingness to move more. Being healthy, breaking away from work, reducing stress and getting rewards are common themes here.

There are also “stray” notes that aren’t in any category, but they provide some contradictions and surprises we have to consider for individual users. For example, one note says “feel sleepier when stretching” and the other says “feel energetic when stretching”. This suggests that it’s important to tailor specific movements to individuals. There are also notes about making fewer movements when focusing, which points out an important factor of reduced movements: “fermenting”, i.e. losing the will to move whether due to external pressure or internal needs for rest. Last but not least, some people voiced concern on manual logging and preferred automatic tracking by the app, which came from the limitation of our baseline study but showed the need for a smarter approach to gathering user routines.

Frequency Chunking

Ordering the categories by the number of notes they each have, we can see that motivations lead the first, followed by environments, with effects being the last. This shows that people want to change their behavior mostly due to the benefits it brings, but most importantly, their own willingness to make the change. External nudging and interventions may work to a degree, but it’s ultimately up to the user’s own motivation. The finding demonstrates the need to precisely choose our target audience.

2×2 Mapping

We also tried to map the post-it notes onto a 2×2 matrix, with the x-axis being from “high activation” to “low activation” and the y-axis being from “high intervention” to “low intervention”. We chose these two axes because they are prominent in behavior change apps on mindfulness and fitness.

Many notes mentioned the importance of balance between high activation and low activation, as well as the participants’ feedback on manual logging and reminders. This is consistent with the conclusion from our comparative research (shown below).

We aim to place our product somewhere in the middle. Even though we categorized most of these apps into “high” or “low” levels of intervention, we aim for “smart” intervention: this means intervening at times that are actually useful to our user, instead of a set number of times throughout the day.

Models

Connection Circle

This was the first model we used to design our intervention. To make this model, we first collected all of the factors that we found impacted movement, from the synthesis of our baseline research. After writing these factors on the outside of the circle, we then linked them together with positive and negative impact arrows (orange and pink, respectively). We found a ton of connections – since there were so many, we decided to also use an interconnected feedback loop model to pull out cycles, and actions that fed into those circles.

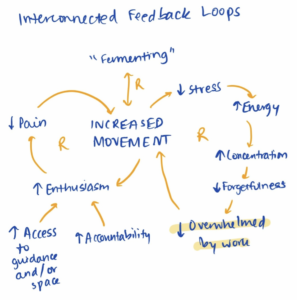

Interconnected Feedback Loops

Based on the connection circle, we also made feedback loops to further investigate the casualty. This was what we learned from the Interconnected Feedback Loops Model above, which includes all of the factors from the original Connected Circles model:

- We found two reinforcing feedback loop circles (the left and right circles). This means that these cycles could either be compoundingly bad, or compoundingly good, depending on the color of the arrows! For example, more movement could lead to more enthusiasm, which could lead to less pain, which could lead to more movement. However, more pain could lead to less movement which could lead to less enthusiasm, and thus more pain. So, making one link in these cycles positive could have a hugely positive impact.

- From our research, we knew that being overwhelmed by work and/or forgetfulness were the main reasons why participants were not able to engage in mindful movement as much as they wished they could. From this model, we saw that not only were these 2 factors linked, but also, many other factors fed into their cycle; as mentioned above, switching just one of these links to a positive instead of negative impact would eventually increase mindful movement.

- We also found that one of the factors we had written, “Fermenting”, was actually just the exact opposite of “Increased Mindful Movement”; decreasing fermenting was the same as increasing movement, so we did not need to focus on this factor specifically.

- Access and accountability fed into cycles which affected movement, rather than being key factors in making or breaking a person’s movement. This was gleaned from the Connection Circle as well as baseline study data.

From our synthesis and models, we hypothesize that users can build up the habit of mindful movements by making one or more of the existing links positive. We think that appropriate and timely reminders could help people become less forgetful about movement, which could make them less overwhelmed by work, which could then feed into a positive cycle. We think this will work as long as users are willing to listen to the reminders, and the intervention shows them the positive impact through time.

Proto-Personas and Journey Maps

Our behavioral personas are a combination of our participants based on our interviews and baseline diary study data. We assessed that the most distinguishing factor differentiating our participants’ activity level, habits, and routines were their occupations. Our participants included employees ranging from more sedentary to more laborious occupations, to students who have more variety throughout their day.

After evaluating our findings, we decided to divide the personas into three categories, all full-time: university student, physical labor employee, and work-from-home employee. (Note: We had an office worker as one of our participants but absorbed their data into the university student category because their routines and activity level were so similar, and we had more student participants but only one office worker.) We feel that these personas cover the range of occupations and schedules that most working adults (ages 18-60’s) fall under. We decided on occupation as our defining factor, because while there are differences between each type, it still allows people of various demographics to be included. This is because we believe the habit we want people to improve – moving more mindfully, more often – is one that can benefit most people so we wanted to be as inclusive as possible.

There are some groups of people not represented in this data, such as minors, retired people, and unemployed people. Because our personas are based on our data, the main reason for our exclusion is due to a lack of data on such participants. Thus while we think our intervention idea may even be beneficial to people not included in these personas, it is worth noting that for the scope of this project, our audience is limited to working adults (including students) who have access to phones.

Persona + Map #1: University Student “S.T.”

S.T. is based on our data of various students interviewed plus an office worker. Their schedule has both a level of variety and predictability. They may move between places and obligations such as meetings. Unlike the other personas, S.T. is prone to feeling more oscillations of stress and energy throughout their day. Their busy schedule and multiple responsibilities makes practicing mindful movements challenging in a way that’s unique to them, which is why we felt this persona is worth investigating.

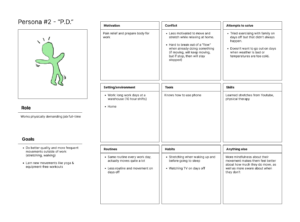

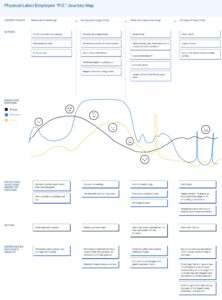

Persona + Map #2: Physical Labor Employee “P.D.”

P.D. is a persona based on our data of people who work in warehouses. Unlike students and office workers whose activity levels are relatively more sedentary or flexible throughout their day, P.D. works a more physically demanding job with more continuous hours being active, as well as a trend of being almost completely inactive on days off. P.D. actually moves a lot throughout their work days, yet still felt lacking in their habit of mindful movements, especially on days off. This means P.D. has different needs than our other personas, which makes them worth investigating.

Persona + Map #3: Work-From-Home Employee “W.H.”

W.H. is a persona based on our data of multiple work-from-home employees. What distinguishes a work-from-home employee from the other workers is their work place. They are more sedentary and isolated than a labor employee. And even if they could be similarly sedentary as an office worker, working from home means a more restrictive space, thus less ability to move around, and fewer face-to-face interactions with others, which can have an impact on their health and wellbeing. Thus we believe W.H. is a distinct persona worth investigating.

Further Insights

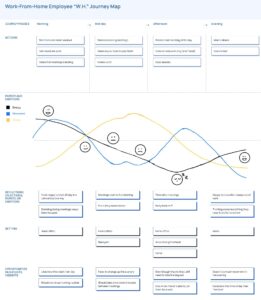

Even though we have personas who each have distinct occupations, activities, and needs, we were still able to find commonalities between them that helped inform our intervention ideation. Looking at both the personas and journey maps, we were able to parse out several things:

One thing we noticed is that people generally feel more positive and energetic in the beginning of their days. However, they then lose energy after working for extended periods of time. This decrease in energy means people are more tired and fatigued, which exacerbates issues like forgetfulness or a lack of motivation. Usually the increase in work and decrease in energy also correlate with increased stress, except at the end of the day when people have lower energy but less stress because they are winding down for the day. In addition to stress and fatigue, everyone is also dealing with pain, whether from a lack of activity (e.g. too much sitting) or too much activity (e.g. overwork). Based on our interviews, participants have expressed that mindful movements, such as taking walks or stretching, can help relieve some of this pain.

We also see that there are points when people need breaks or crash due to tiredness. During these low points, participants told us they would benefit from doing mindful movements, yet we can see from our personas and journey maps that they do not usually end up doing them, instead having told us in interviews that they want to or should but don’t usually take action. Instead, they usually opt to do passive activities that are more easily relaxing or rewarding, like watching TV. When that is not the case, then the reason for not moving is can be due to feeling overwhelmed, busy, forgetting, a lack of motivation, or maintaining a state of inertia, meaning when people are in the state/flow of already doing something, it can be difficult to disrupt that state with other actions, especially using only self-motivation. Our data reveals that external forces can pull them out of a state of inertia. Examples from our interviews included having to take out their dog (break from work), exercising with a buddy (break from fermenting), or receiving a reminder (applicable anytime). It is worth noting that the reason an external force might not always work is because it may not always align in a convenient way with participants’ schedules. Reasons brought up in interviews are that sometimes workout buddies are unavailable, or sometimes pre-set reminders go off when a person unexpectedly finds themselves too busy with something else. Without an external push, people can succumb to various reasons for not moving, like forgetfulness, lack of motivation, or feeling overwhelmed.

That brings us to our intervention ideas, all of which act as that external push. We brainstormed ideas based on things like convenience and intrusiveness, social pressure and accountability, incentive and reward, and fun/enthusiasm. We narrowed our ideas down to three.

Intervention Ideas

Connection Map and Decision Process

After synthesizing our data from the baseline study, we created the aforementioned connection circle to model the various themes and actors surrounding mindful movements. After drawing connections and identifying causal loops that contribute to/take away from the habit of consistent mindful movement, we brainstormed a variety of interventions. We narrowed the ideas down to three possibilities that addressed different aspects of the connection circle and discussed the pros and cons of each.

Idea 1: Sending Conditional, Convenient Movement Notifications

Description

We will send our users prompts to move at relevant times, based on their calendars, which they will send to us. Then, we will track when & how much they moved each day using an EOD survey. We saw this as a potential solution to address forgetfulness in our connection circle and synthesis since our multiple reminders throughout the day would ensure the participants know when they should be moving. Additionally, this would help address being overwhelmed with work/commitments since we would be taking the load off of participants to remember when to stretch or move mindfully. This idea is also an attempt to improve upon an app studied in our comparative analysis, StretchMinder, which only gives hourly reminders instead of smart reminders based on a user’s schedule. Strethminder’s reminders seem to have a positive correlation with user behavioral affection when they’re able to, but does not take into account user’s unique routines, which we saw an opportunity to improve upon.

Pros

- Flexible with people’s schedules.

- People might already have time in between commitments to do movements.

- Leaves room for type of movement/duration.

- Guides people on when to do the movements, helps when participants are forgetful.

Cons

- Requires consent / a level of intimacy to get everyone’s calendar.

- People also have to make a calendar in the first place.

- People might not want to receive notifications/want to have their ringer/vibrate on.

- We would have to be conscious of their schedules to send the reminders/logistics may be difficult.

- People could ignore the notifications.

Idea 2: Accountability Partner (Social Pressure)

Description

We would have each person text the movement they want to do each day to us (set a goal / intention first!) and then check in on how they did at the end of the day. We will encourage them/motivate them based on how they do. This would induce social pressure and motivate the user since they don’t want to let down their partner. This would address the lack of partner factor on the connection circle by having one of us engage as an accountability partner for the participant. The daily reminder feature would address the forgetfulness theme that came up in our synthesis and connection circle. This is a similar concept to Movejoy that pairs people with fitness accountability buddies. When doing comparative research, we found that when users found someone to hold them accountable, they were much more successful in habit changing. However, a lot of energy is needed for participants to meet which leads to many unsuccessful results if there are problems finding a consistent accountability partner. Thus, rather than making the participant meet with us, we would simply engage in text message discourse and a survey to remove friction.

Pros

- Combines the benefits of socially moving with the benefits of mindfully moving.

- Possibility to get support outside.

- Social pressure encourages people to move even if they don’t feel like it.

Cons

- People might not actually feel accountable to us (study moderators).

- Could feel too much pressure to commit to a buddy and not “sign up” in the first place.

- Won’t have anyone to actually do the moves with them/we are not also trying to move more.

- End of day check in might not be frequent enough to get participants to remember.

- Doesn’t connect them with a larger community.

Idea 3: Gamification with Points/Badges

Description

We would send people affirmation/pictures of things they “win” every time they move. Ask them at the end of every day how much they moved. The incentive would be stats-based, and we could give points every day and/or they win badges. This induces a sense of competition, with an aim to address the enthusiasm aspect of the connection circle, since gamifying the process could increase the enthusiasm to engage in the movement. We also thought to emulate the tactics of several apps in our comparative analysis, for example filling the rings in the Apple Fitness App or unlocking creatures in StandLand. Users described how aspects of these apps motivated them to continue the habit the apps set to change (with one user describing how although the behavior started simply because of the game of Standland, it became an ingrained habit that they have done everyday for two years). We thought that by creating a unique, gamified system like these, we would be able to create a similar effect which would offer external motivation and incentives to users to complete otherwise potentially forgettable tasks.

Pros

- Users are able to see immediate gratification/results from their actions.

- Dopamine hits.

- Consistent motivation to improve.

Cons

- Focuses on external motivation vs intrinsic motivation (thus less likely to do action without incentives).

- Perhaps a little cheesy at this stage since we can’t actually give them anything / we don’t have an interface that gives them things.

- Defeats the purpose of wanting to move mindfully if they are thinking about moving to win points.

- Not represented as a big pain point in our synthesis or connection circle.

Final Decision: Idea 1, Convenient Movement Reminders

We came to this decision because we saw the most promise for changing behavior in this tactic. Through our baseline study we saw that our participants wanted to engage in more mindful movements throughout the day, but either their schedules were too busy, they lacked motivation, or they forgot. By crafting a notification schedule that aligned with a participant’s schedule as well as desired times and movements, we hoped that the nudges could be more successful in implementing the habit. This was especially true for our participants that fit in the work-from-home persona because they might have strict schedules with back to back meetings, and may need reminders that don’t interfer with their work calendars. We also saw that the college student persona struggled to make time or remember to move, so a convenient reminder would address that conflict to remove barriers to movement. For our third persona, we noticed that people with physically demanding jobs may lack motivation to move at home, so our reminders would seek to provide encouragement with a reminder as well as a suggested movement to make it easy and effortless to incorporate the mindful movement. Additionally, through our comparative study we identified that our optimal solution would lay in the middle of high and low activation and high and low intervention. This intervention tactic of convenient movement reminders will have a smart amount of intervention based on user preferences and a smart amount of activation based on the time and location of the participant, making this strategy the most effective.

Questions To Answer (Hypotheses)

- How will convenient movement reminders that are catered to a participant’s schedule impact how often the user engages in mindful movements?

- How does the social pressure from requiring the participant to respond “YES” when they complete the movement impact the user’s motivation to complete the mindful movement?

Intervention Study Protocol

Who To Recruit

We recruited a mix of old participants from our baseline study who we know want to improve their mindful movement habits and new participants who could provide us with fresh perspectives. We also aimed to recruit participants who fit under our 3 user-personas: work-from-home employee, physical labor employee, and university student. This includes people who work from home and are sitting most of the day in meetings. This also includes labor employees who are actively standing and working manual labor throughout the day, whose bodies hurt if they don’t stretch regularly. Finally, this includes students who might be sitting in classes or studying for most of the day, or who have busy schedules and don’t make time to move mindfully. Our personas range from young adults to older adults and are not limited by gender. It is worth noting our participants and personas so far all represent relatively able-bodied people but our goal is for our ultimate product to still work for many people with disabilities as well, as long as they can use a phone app and benefit from doing mindful movements. Due to the scope of this class, limit on time and resources, and because our research does not indicate this is a priority audience for our product, we will unfortunately not cover such demographics at this time.

Data To Collect

We plan to collect 3 types of data:

- Daily prompt responses:

Some participants will be asked to respond YES when they engage in a mindful movement in response to the prompt.

- End of day surveys:

Survey responses will recap the percentage of times they moved in response to the prompt, as well as reflections on the type of movements and emotions they felt afterwards.

- End of study survey:

We will have all participants reflect on the intrusiveness of the prompts, how they felt about receiving reminders, and how successful they felt the intervention was in helping them move more.

Data Collection Plan

The following outlines our data collection plan:

- Either meet with (if new) or email (if old) all participants to brief them on the study procedures for the week. Collect from them their schedule for the week (screenshot or share access), as well as responses to the following questions:

- Can you tell me general times or events during which you would like to be reminded to move (e.g. during a long meeting, after any meetings or classes, in the mornings when I wake up, etc.)?

- Can you tell me what types of movements you would like to be doing this week? In this way, I can tailor the prompts to encourage specific movements that you want to do.

- What is your phone notification method right now for text messages (silent, vibrate, ring)? Would you like to change it to vibrate for this study?

- We will each then tailor a texting schedule to each participant based on their calendar and desired times and movements. Each day we will send participants anywhere from 2 to 5 reminders throughout the day with a suggestion for their desired movement. Half of the participants will also receive instructions to respond “YES” if they have been engaged in the movement.

- At the end of each day, we will send participants a text with the link to the daily survey.

- At the end of the week, we will send participants a text with the link to the end of study survey.

Comments

Comments are closed.