CS 247B: Design for Behavior Change

Team 15: Mindful Movements

Amantina Rossi, Uma Phatak, Nadia Wan Rosli, Melody Fuentes, Rui Ying

Problem and Motivation

In an increasingly rushed world, it can be hard for people to make time, much less remember, to commit to mindful movements in their day-to-day routines, such as a deep stretch or even an intentional breath.

As students navigating the digital age, many of our “grind” sessions involve hours glued to our devices. When not working, we’re likely sitting through lectures, scrolling through our phones, socializing with friends, or generally rushing from one event to the next. With such business, it’s easy for mindfulness, and taking time to be kind to ourselves and our bodies, to slip our minds.

We find that we’re not alone. This is not a phenomenon specific to the coffee-addicted student. People from all identities – from the physical laborer to the work-from-home parent – struggle to maintain habits around intentional movement. But with such a beneficial and feel-good action, why?

So for our design challenge, we ask: How do we create long-term habits around mindful movements?

Baseline Study

Target Audience

Our target demographic are those who routinely spend long periods of time in their activities and have a desire to build habits around mindful movements. We screened participants through a Google form, looking for those who especially work for long, uninterrupted intervals and express interest in mindful movements.

Protocol

In our pre-study interviews, we investigated if mindful movements were a habit they tried to cultivate in the past. If so, we wanted to know what did and didn’t work in their experience. We looked for what mindful practices meant to each participant, both in connotation and personal experience, and their reasoning for wanting to build this habit.

For the baseline study, participants self-logged their activities related to mindful movements (stretching, meditation, etc.) every waking hour for 5 days. Every hour, they would note down the time, what mindful action they took, if any, and how long that action was. Information we were looking to collect revolved around questions like: What time is the participant normally active? When and how often does the participant make a mindful movement? What kind of movement does the participant do? It gave us great insight to see the regular habits of our participants and make note of where we could intervene.

For a more detailed description and design of the baseline study, please refer to this document.

Synthesis

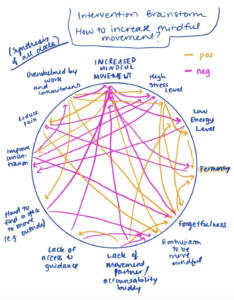

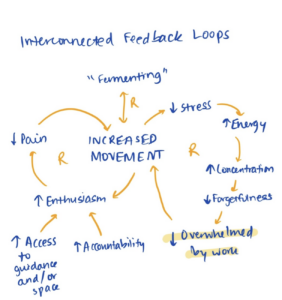

We made a connection circle and an interconnected feedback loop model to gain insight into how common factors affect mindful movements. From these models, we learned which factors are the biggest hindrances towards our habit creation (i.e. forgetfulness and business), using this as a stepping stone to brainstorm how to increase the positive behavior we want. We also gained ideas as to how to make “mindful movements” an intrinsic, enthusiastic experience through positive feedback loops.

See the “Personas and Journey Maps” section for more synthesis results.

Comparative Research and Analysis

Competitors

Most participants from our baseline study indicated that they wanted to move more for the sake of their well-being, but had difficulty keeping at it. Therefore, the comparative research focused on fitness/health apps to look at how they promote physical health, as well as a handful of mindfulness apps for mental well-being.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The competitors come from a variety of spaces. However, regarding mindful movements, they all have their respective strengths and weaknesses: apps that do tracking feel more motivating but not necessarily in the direction of mindfulness; apps that start small might do better in habit forming but are limited to a certain set of activities; apps that focus on mindfulness can be lacking in the mental health aspect.

Based on the analysis above, we think it’s important to have an app that is not only good at motivating physical health (movements) but also effective in mental health (mindfulness). We clearly see that there is a huge vacuum in such space and we plan to fill the void with our product.

Where Our Competitors Stand

To further understand our competitors and help us pin down the design directions of our final product, we did 2×2 mapping for all apps.

We found that the apps researched above can be roughly mapped onto a matrix of two axes: level of activation (energy needed to use the app) and level of intervention (how often the app reminds users to do something).

Where Our Product Will Stand

From the findings of our baseline study and the comparative research, we decided to place our product somewhere in the “middle”, with a “smart” intervention level and a “flexible” activation level that comes from personalized movement choices.

We believe that the app in the “middle” can provide enough nudges to effectively change users’ behavior while not being too intrusive or annoying to be discouraging, and an appropriate level of activation that caters to individual users’ preferences will make the behavior change more enjoyable.

For more detailed app walk-throughs and analysis, see this blog post.

Literature Review

To get a better idea of intervention and support it with scientific findings and reasoning, we looked through related literature. Some of the papers are about the effect of movements on physical and mental well-being; others focus on mindfulness and its relation to stress, attention and even work efficiency.

Insights and Learnings

We gather insights from these papers and see how they can guide our intervention idea and our design process.

- Mindful movements can help with chronic pain, reduce stress and may improve work efficiency. These are wonderful benefits that motivate our target users.

- Breaks and intervals are essential for mindfulness to take effect on attention, stress or efficiency. These findings show that our product needs a good scheduling/reminder system for mindful movements to achieve better results.

- Some elites use mindfulness as a tool for profit. When we design our product, we should put users’ well-being above everything else; we should closely examine the ethics of our intervention idea and prevent manipulative nudges by giving opt-out options.

For the full literature review, see this document.

Personas and Journey Maps

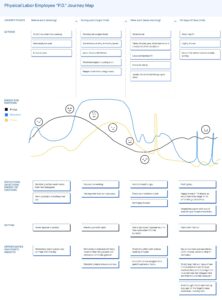

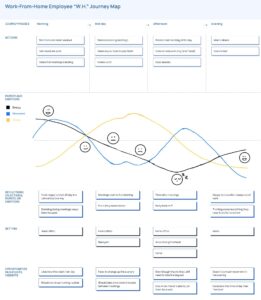

Based on our research data, we created personas centered around three distinct occupations, as we assessed that was what differentiated our interviewees’ routines and activity level the most. Combined with our diary study data, we created journey maps that reflected each persona’s activities, emotions, and wellbeing over time to explore at which points in their routines may users benefit most from mindful movement interventions. We discovered that people experience certain rhythms in their day based on what activities they were doing and for how long they had to engage, finding people generally start their days strong but end up tired/inactive. We believe adding mindful movements interspersed throughout their days would give more stable positive effects.

For a detailed breakdown of personas, journey maps, and insights, see this post.

Intervention and Product Ideation

After synthesizing our data from the baseline study, we created a connection circle to model the various themes and actors surrounding mindful movements. After drawing connections and identifying causal loops that contribute to/take away from the habit of consistent mindful movement, we brainstormed a variety of interventions. We narrowed the ideas down to three possibilities that addressed different aspects of the connection circle and discussed the pros and cons of each. The first idea was sending conditional, convenient movement notifications. The second was establishing an accountability partner to induce social pressure. The third idea was gamification with points/badges.

Our final decision was Idea 1, Convenient Movement Reminders. We came to this decision because we saw the most promise for changing behavior in this tactic. By crafting a notification schedule that aligned with a participant’s schedule as well as desired times and movements, we hoped that the nudges could be more successful in implementing the habit. For more details about the justification behind our choice, see our in-depth Intervention Brainstorm blog post.

Intervention Study

We designed an intervention study protocol for our best idea, linked here. Broadly, we asked users for their calendar schedules for the week of 2/6 – 2/10, asked them when they wanted to be prompted to move and what types of movements they wanted to be doing, and then texted them at the relevant times. We collected their feelings and movement levels via an end-of-day and end-of-study survey. Then, we synthesized this data.

First, we used a connection circle model. We found that while the effect of mindful movement was standardized across the board – people always felt more calm – the factors that increased movement were not. Many factors (e.g. how busy users were when receiving the prompt, how stressed they were when receiving the prompt, the level of social accountability) could either help or hurt affected people’s movement levels, depending on the person. This indicates the need for customizability.

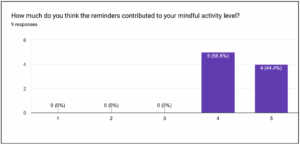

Ex. Some findings were conclusive, like everyone’s agreement that reminders contributed positively to their activity levels. (1 means “very little contribution”, 5 means “very much contribution”.)

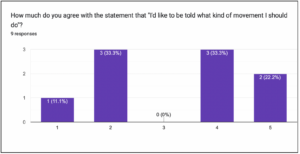

Ex. Other findings were more nuanced, like the insight that some people like to be told what movement to perform, while others do not. (1 means “strongly disagree”, 5 means “strongly agree”.)

Our key insights were:

- Different persona groups needed and wanted different things.

- In order to accommodate all personas, we need to allow users to customize various aspects of the prompts (language, timing, frequency, etc.)

- We need some way to re-prompt people who are simply too busy to move at the moment.

- We had limited success intrinsically motivating people to move, without our consistent prompts – how can we improve upon this?

For more detail on the intervention study and data synthesis, see this document.

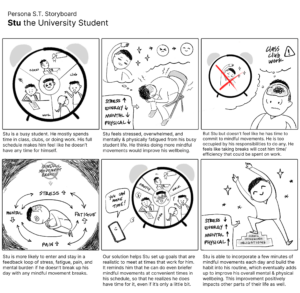

Storyboards

Persona #1: Student “Stu”

Insights

- Student’s perception is that they are too busy/overwhelmed to make time for mindful movements, even if they have a desire to do so.

- Most useful to help the student persona realize where there is time in their schedule to do mindful movements (one thing to note from the journey map is a lot of students waste time looking at their phones aimlessly).

- May have to convince them of the benefits of taking the time to do mindful movements.

Persona #2: Physical Laborer “Pat”

Insights

- Physical laborer incorporates mindful movements in their work day routines but has trouble doing so on their days off for various reasons.

- They most benefit from extra assistance to get them moving on those days.

- Reminding them of their goals in addition to moving may help with motivation.

Storyboard #3: Work-From-Home “Wanda”

Insights

- WFH employee’s schedule is packed with long periods of sedentary work in isolation.

- Need to help them relieve pressure from the job by fitting in movements that align with their changing daily schedule, like after meetings.

- This means we cannot schedule reminders based only on “time” but also on “events.”

Future Directions

Our intervention study proved that sending conditional, convenient movement notifications based on a user’s schedule and desired movement types was successful in helping users more regularly incorporate mindful movement into their daily routines. Therefore, our group has decided to move forward with this idea of smart notifications. This ties back to our comparative analysis where we determined that applications with the optimal amount of activation and intervention were the most successful. As a team we brainstormed various features of the application, including what the onboarding process would look like, how users would respond to notifications, and what our ideal outcome would be.

As we move forward, we would like to build on our intervention study idea with more behavioral theory around rewards. After sending users a convenient notification, what can we do to motivate them to move in response to the prompt? Some initial ideas are confetti animations when completed, guided exercises, and other tactics to increase intrinsic motivation. Ultimately, we hope to create an application that is easy to use. Once the user sets up the app with their calendar and preferred movements, they can rely on the app to remind them to move mindfully throughout the day, and eventually be able to do the habit on their own.

For a more detailed breakdown of how the intervention study guided our future directions, see the last section in this document.