Problem Finding

At the beginning of the quarter, our team was broadly interested in how we could encourage Stanford students to get out of their comfort zones, especially after the past 2 years of isolation brought on by the pandemic. We had a shared interest in mindfulness and exploring creativity, and had concerns about students at Stanford feeling like they could not express themselves creatively because of a lack of experience or skills. We wanted to find a way to empower folks on campus to incorporate creative practices into their daily lives.

Literature Review

We looked at research done in the field of creativity, habit formation, and time management. One key finding found across multiple studies done on habit formation and creative practices was that people were more inclined to maintain habits or explore their creativity when they felt intrinsically motivated. This helped us frame our solution, as we realized it would be important to not just throw in superficial extrinsic motivators into our app. Other studies revealed that measurements of creativity in general were unfairly biased towards Western cultures and ideology (thus skewing results for assessing creativity ability), and suggested further research that would more fairly assess creativity in other cultures. These studies encouraged us to think critically about how to evaluate what motivates people and check our own biases when developing our ideas.

Comparative Research

In our research, we found that while some existing apps use effective nudging, many others range from being overwhelming to the user or completely failing to prompt the user towards any action. One positive example of nudges was the Brainsparker app notification system, which only allowed a maximum of 3 nudges a day. If we continued to build the app, we would use our positive comparators to develop an effective notification system.

Overall, looking at the solutions that currently exist in this space gave us potential ideas for effective nudges but also demonstrated a gap in community based approaches to encouraging creativity.

2X2 that places the apps we looked at in terms of the social/community aspect of it and it’s scientific validity

Baseline Study

For our baseline study, we selected students who expressed having difficulty incorporating creative practices into their daily lives and had a desire to be more creative on a regular basis. We wanted to learn more about how people structure their days, what their different creative interests are, and how they incorporate creative practices. We asked them to fill out a quick daily survey where they briefly summarized their day and described a creative activity they did.

We learned that people want to try creative practices but feel constrained by time and lack of ability. We saw that people were more inclined to follow through on doing something creative if it was done in a social setting or a dedicated class that is already in their schedule. We used our findings to refine our problem statement to further focus on how we could motivate people to be creative on a daily basis alongside their friends.

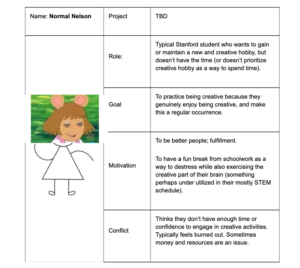

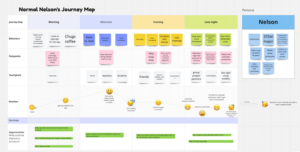

Persona & Journey Map

Based on our diary study finding that few people express themselves creatively in their day-to-day life, we developed a persona of a typical Stanford student named Normal Nelson, who finds themself too busy with classes and socializing to engage in creative activities throughout their daily life.

In our journey map, we saw that happiness peaks in the middle of the afternoon, and emotions become more stressed and sad as the day progresses. Some key areas we found that we could improve are the mornings and the late nights where students might need a creative outlet as a brief break to refresh themselves.

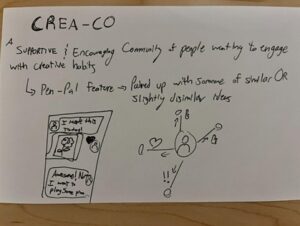

Storyboards

We saw a common pattern of people finding motivation to do creative work when they plan to do it with friends. One storyboard we mocked up, Crea-Co, is centered around having a community of others where you all can collectively engage in creative habits.

Solution Finding

Intervention Ideation & Synthesis

Our interventions were informed by the insights from our baseline study and comparative research. In our comparative research, we found that many solutions for building habits focused on self-motivated and personal habit tracking, and had an emphasis on learning more about whatever habit the user wanted to build, not necessarily allowing the user to build on their own skills the way they wanted.

Since we found that users were more inclined to follow through on doing something creative if 1) it is a social activity and 2) many existing solutions focused on independent habit building, we chose to test an intervention that would engage participants more socially with creativity-inducing prompts.

Designing an Intervention Study

In our intervention study, we sent participants creativity-engaging “prompts” from someone on our team throughout the week. On top of the “social” aspect of the intervention, in which the participants would send their art or prompt interpretations to a real person and get a unique response, we incorporated multiple habit-building techniques in our intervention, such as anchoring, small-ification, accountability, reducing difficulty, and celebrating wins.

To find potential anchors for our participants, we sent out a survey for participants to detail when they have free time to personalize the timing of the prompts we sent out.

The prompts themselves were quick, easy-to-do suggestions to either start or finish a drawing, painting, photo, or creative idea that was started by the accountability partner (aka, us!). This reduced the difficulty of coming up with an idea for what to create, and tapped into participants’ inclinations to engage with things that felt collaborative and where their input was valued.

After the participant responded to the prompt, we responded back with praise and enthusiasm to celebrate their engagement. If they did not respond to a prompt, we embedded accountability by sending them another nudge to try out the prompt again at a later time.

The intervention study helped us learn what kind of collaboration could be most effective for a social creativity app, which was the direction our team ultimately decided to take. If we could do the intervention study again, given the highly social nature of our final solution, we would enable participants to engage with other participants in creativity prompts, rather than with us. This would have given us better insight into how participants would engage if they could do it with someone they were already comfortable communicating with.

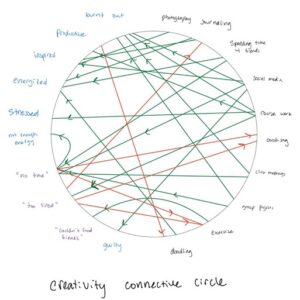

Mapping

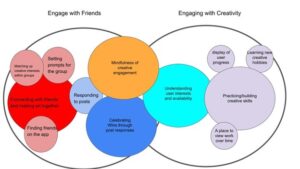

We created several different maps to visualize the problem space and inform what a solution could look like. This included a connective circle, bubble map, system path diagram, and assumption maps.

Our bubble map helped lay out our solution’s main themes and clarified what aspects were overlapping, missing, and unneeded. Mapping the systems for creativity against the systems for engaging with friends ultimately led us to the design of our prototype, although the system path diagram helped us more so towards the end of the design process, once we knew what we wanted to do and needed to map out the how. We definitely would use the bubble map in the future and in other projects, particularly once the problem space is more defined and the team is trying to understand the main goals we are trying to solve and how those goals interact with one another.

Assumptions Mapping

Our bubble map and system path diagram helped inform our assumption maps, which were done after we had a high-level view of the goals of our solution. The assumptions maps helped identify a few key assumptions, with the most important assumption being the following:

- Will people actually prefer to get prompts from friends, and to also invest time in creating prompts for others?

We hypothesized that participants would enjoy getting prompts from friends over a random person, and designed a test in which participants received a similar type of prompt throughout the week, but the way it was given to them changed each day. On day 1, they received a prompt that was “pre-generated”. The next day, their prompt was “made by one of their friends”. On the last day, we had them create and submit their own prompt, which we added to a list of prompts that other participants generated and sent it back to them. By seeing their own prompt in the mix of other prompts, participants could see that each prompt was created by another person. Afterwards, we surveyed participants on which method of receiving a prompt they preferred.

We found that the results of assumption tests aligned with our hypothesis. One interesting insight from testing the assumption about getting prompts from friends was that participants often tried to guess who suggested which prompt in the list, but enjoyed getting the list of prompts that were generated by other people over app-generated prompts even when they didn’t know who suggested the ideas. This test informed our approach to the solution prototype, as we included elements of personalized feedback channels and prompt-creation mechanics.

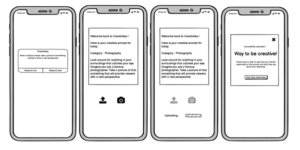

We designed five separate wireflows that comprised the bulk of interactions we expected: login, home page and essential screens, creative prompt creation/submission/voting, notification and submission of creative work, and giving/receiving feedback. Each wireflows showed off hand drawn screens that a typical user might see and interact with in the course of their general usage of our app.

Some examples of our wireflows.

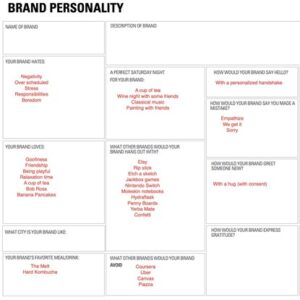

Brand Personality – Mood Board and Style Tile

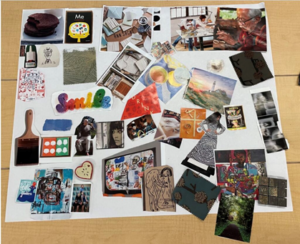

To narrow in on the feeling and mission we wanted for our app, we created a brand personality sheet, physical mood board, and style tile! We envisioned our app as an upbeat, optimistic, and laid-back environment which encouraged all types of creative practices. This vision carried forward into our mood board, where we perused artsy magazines for fun, playful imagery to cut-and-paste onto the large collage pictured below. Our style tile then translated this creative feeling into a working color palette and font that our final prototype would use. With ‘goofy’, ‘playful’, and ‘collaborative’ as a guide, we settled on a white, turquoise, and orange color palette accompanied by the Lora font as our style for our prototype.

The brand personality sheet served as a first pass for the feeling we wanted our app to evoke.

Our mood board, which embraced the vibe of playful creativity!

The final style tile used to design our final prototype

Our team made sketch screens and task flows that we considered to be vital for the user experience of the app. We worked on the signup and onboarding flow, creating or joining a new group, uploading a response or responding to and receiving feedback on the group page. We also worked on the flows for responding to push notifications for the current prompt, and push notifications when users give or receive feedback.

Caption: An example of a task flow (push notification to get current prompt)

We used inspiration from our sketchy screens combined with our moodboard, style tile and brand personality to create the clickable prototype. The link above shows the final prototype after incorporating feedback from usability testing, initial review and presentation critique.

Usability Testing

We conducted initial usability tests on fellow students with our prototype to identify problems that users might have. Using a small testing script, we asked testers to complete several key tasks within our prototype, and took notes on their actions, complaints and feedback.The tests revealed three issues in particular:

Issue 7 (moderate-severe): The “create/add to group” screen was unintuitive. Visual hierarchy was also weak, as the user was slow to recognize certain headers and mentally arranged certain fields from different sections together.

Issue 8 (severe): Create/join group page was confusing. One user commented that this page was cluttered and it was unclear that you could do both functionalities.

Issue 9 (moderate): Our notification page lacks organization, has too much text, and displays all notifications sequentially on a single page. One user commented that it is overwhelming having to sift through all the notifications to find the relevant one.

Each of these three moderate/severe issues required a conceptual reimagining of their corresponding screen’s structure. We did an overhaul of the create/join group screen to fix problems 7 and 8 simultaneously, by dividing create and join into separate screens and making hierarchical changes to both. We also reworked the notifications screen to be more organized and informative at a glance. Given more time, we would investigate the following issues:

- Notifications:

- How can we leverage anchors and / or send notifications at a time the user is most likely to respond? If there was a way for us to know that our user finished class and had 30 minutes before the next, we could send a notification then.

- Tutorial and cold start problem

- When a user first joins the app, we could guide them through an intuitive tutorial that teaches them how to use the essential features of our app. In the tutorial, the user would learn how to join a group with one of the creators of the app (one of us, or a simulation of us). This way, they understand the concept of a group and what you can do in it (respond to a prompt, upload a prompt, etc).

- After this quick tutorial, we would provide an easy way to share a link to their friends to add people to the group. If the user prefers not to, they can also use the group created from the tutorial as a way to keep using the app without requiring other friends to join.

- Teaching creative skills to others

- It would be amazing if someone with a certain skill could teach it to others on Creativitea. In the future, we want users to be able to create “events” that other users can access.

Ethical Analysis and Broader Impacts

Nudging and Manipulation

We wanted to anchor nudges to times when users are likely to be free and have the energy to work on something creative. We were concerned that Creativitea would be viewed as yet another stressful task in users’ days, and tried in our intervention study to only nudge participants when they had free time. We also gave users a “remind me later” option on push notifications to lessen mental load in the moment.

However, there is a chance it could still become manipulative. If a user feels pressure to complete a task right when they receive a nudge, they may stop whatever they are doing to complete the task immediately. This could be harmful if they are not actually free right then or too tired to do the task. We do not want to manipulate people into responding immediately if that means we are taking away from their time spent with friends and family or restoration time with themselves. If we had more time, we would do a study on wording our nudges to find which ones are the least stress inducing and brainstorm more ways to ensure that our nudges can be ignored without leading to anxiety within users.

Privacy

Our biggest privacy concern is protecting users’ creative work and giving them control over who they share it with. Creativitea allows users to keep track of all of the creative work they made based on prompts from the app in their Gallery. Each user’s Gallery is available to them and their friends, and shows their creations in the app. Given more time, we would expand the settings page so that users could have visibility controls over their media. One other issue stems from how user stories are publicly visible to users’ friends and group members, which would only be viewable for a limited period of time in future iterations. We would also expand our settings page to allow for control over story visibility, removal of content from stories, and reporting of stories. Another worry is that a user could screenshot someone else’s story or group chat content and share it with people who do not follow the poster without the poster’s consent, which we could alleviate by notifying users if their content is screenshotted.

Interface Design & Design Justice

As mentioned in the Design Values reading, research shows that designers assume users are “white, male, abled, English-speaking, middle-class US citizens, unless specified otherwise.” We wanted our app to have the “freedom from bias” mentioned in the Design Values reading. Our original persona of the uncreative, “typical stressed out Stanford student” Normal Nelson was biased towards a subset of students who did not normally spend time on creative acts. We wanted to expand our definition to students who already have creative hobbies but want to improve or share them with friends, and designed prompts to be inclusive regardless of a user’s personal creativity. Based on class feedback and assumption test findings, we included a wide variety of types of prompts so that users can use many different creative outlets rather than just drawing or writing. We also tried to include prompts that do not assume people are hearing, seeing, and/or able bodied. If we had more time, we would conduct user testing on prompts on many more people and incorporate their feedback so we could truly go beyond “freedom from bias”.

Broader Impacts

If our behavior change of prioritizing creative time into one’s schedule was widely adopted among busy university students, we would hopefully have less stressed and less burnt out students. We would also have more people who identify as creative, which would hopefully translate into more creative solutions in our workplaces and homes. Additionally, our app includes a social element of creating and sharing together so hopefully we can create new communities and strengthen existing ones through this.

Conclusion

We greatly enjoyed working together, especially in person. We learned that people do enjoy creative breaks, collaboration is compelling, and making an app to change behavior is a nuanced process that even with thoughtful and intelligent design might not lead to actual behavior change.