Overview

Design problem statement: College students and young professionals need a way to ameliorate or prevent bodily pain (e.g., back pain, headaches) that comes with prolonged sedentary behavior from doing work at their desk/computer for extended periods of time without taking breaks.

Target audience: College students and young professionals whose work primarily involves using computers (e.g., office/desk jobs), including both people who do and do not experience pain, as we want this intervention to also be a prevention effort.

Baseline Study

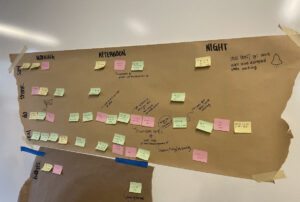

For our baseline study, we interviewed and conducted a baseline study with 8 participants, including 4 students across different universities and 4 workers in different fields, including accounting and software engineering. These participants logged how long they spent on their computers, any breaks that they took, what they did during their breaks, and any bodily pain/discomfort they experienced for 5 days. To identify key insights, we put data from the study, as well as from the pre- and post-study interviews, onto virtual post-it notes on a Miro board. We then used these post-its for affinity mapping, as shown below.

Affinity mapping revealed several different themes, but the most salient ones are as follows:

- Although people express a desire to take more breaks during work sessions, physical breaks are laborious and rarely taken (especially relative to phone/social media breaks

- Bodily pain and/or discomfort is indeed alleviated by taking physical breaks

- People prioritize their work sessions, such that they do not like disruptions to their work flow

- People are generally not responsive to reminder notifications, especially when the action item is too large, but positivity/encouragement in the notification can help

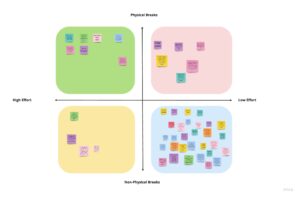

In addition to affinity mapping, we also created a 2×2 matrix using baseline study data, shown below. The x-axis ranges from high effort to low effort in terms of how much effort participants’ breaks took, and the y-axis ranges from physical to non-physical breaks. We then categorized each break description/action into one of the four quadrants.

From this matrix, we noticed that the vast majority of participants’ breaks involved low effort, non-physical breaks, such as going on social media, watching YouTube videos, and reading. This showed us that this was the type of break that we wanted to reduce. Although these breaks can also be beneficial, we ultimately want people to do something to take care of their bodies during their breaks, like stretch. High effort, non-physical breaks, such as socializing with coworkers, can also be helpful, but not the focus of our intervention. As for high effort, physical breaks (e.g., going to the gym), we recognize that these types of activities would not be feasible for our intervention. Especially since insights from the baseline study and interviews indicated that people are not very responsive or inclined to doing large action items, this 2×2 matrix helped demonstrate that the quadrant we should focus on in our intervention is low effort, physical breaks.

Personas

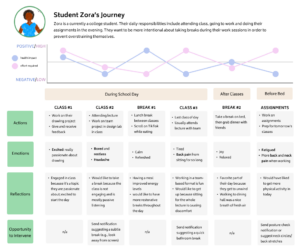

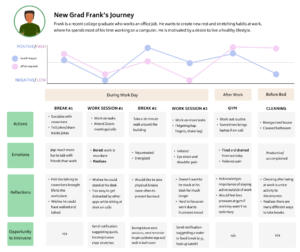

Utilizing the insights from our baseline study, we created two personas—Junior Zora and New Grad Frank. We felt that these personas highlight and represent the prominent behaviors and traits that we observed in our study participants. In order to showcase these personas’ experiences, we also created journey maps for each persona according to each of the proto-personas, as well as data collected from the diary studies, interviews, and secondary sources. Check out the Figma to zoom closer and read the text better.

Junior Zora

Zora is a college student who spends the majority of their time doing school work and studying.

From Student Zora’s journey map, we learned that their main goal is to reduce the physical pain they feel by taking more breaks from using their computer by getting up more, but Zora struggles with a busy schedule with classes during the day and assignments at night and does not like disruptions to their workflow.

New Grad Frank

New Grad Frank is a new college graduate working an office job and thus spends the majority of his time working on his computer.

From New Grad Frank’s journey map, we learned that his main goal is to take care of his body during the workday in order to prevent pain and improve his mood during and after work. However, he has difficulty finding opportunities to take breaks at work, especially finding a way to do things like stretch without embarrassing himself in front of his colleagues.

Intervention

We then used those personas and journey maps to do some time mapping in order to identify opportunities for intervention.

Based on our time mapping, we also created a connection circle that displays the cause and effect relationships between different behaviors/habits throughout the day.

From the time map and connection circle, we came up with 3 ideas for an intervention:

1. Reminders for small action items: send neutral reminders for users to take a break, but with a focus on small action items that are realistically achievable and quick and easy to do

Pros: We recognize that most students and workers can’t just get up in the middle of class/work/in a public space (e.g., library) and start stretching. As a result, recommending small actions that can be done without much effort is more achievable for users. This solution takes users’ environment into consideration.

Cons: A lot of people tend to ignore notifications, which is supported by findings from our study. Furthermore, it is difficult to find the optimal time to send reminder messages, as we don’t want to be too disruptive to people’s workdays or schooldays.

2. Fear/hope messages: send reminders that combine 1) information about the harms of prolonged sedentary behavior or not taking breaks, and 2) a related recommended action to provide hope

Pros: Moderate amounts of fear have been shown to be effective in changing behavior. It is also a widely used and established tactic in a variety of fields, such as advertising and public health. People are also more likely to respond or react to a notification that instills a sense of urgency.

Cons: Too much fear can inhibit someone from taking action and can be ineffective. In addition, some people may react negatively to fear appeals, even if the amount of fear is mild. There may be ethical concerns, but these can be mitigated as long as we are cautious about the types of information/statistics we include in our messages.

3. Every time participants get an email, they should check/fix their posture, roll shoulders, or do a small stretch

Pros: If successful, participants would be building a habit essentially all on their own, as they would have built the habit using internal pressure rather than external pressure. This is also, objectively, a very simple and straightforward study for both the participants and the researchers.

Cons: Because this relies on participants’ own due diligence, it may be hard to execute. It’s a rule that’s easily forgettable, especially because they would not be getting an explicit reminder from an external source. They themselves have to remember to do that action as soon as the trigger happens. In addition, this would be harder for us as researchers to track because we are extremely hands-off.

After reviewing our options, we decided to implement the fear/hope messages. Our rationale for choosing this is rooted in psychological research on fear appeals (Tannenbaum et al., 2015). Research shows that fear appeals are effective, but with moderate amounts of fear. In addition, it has been found that fear messages with recommended actions for the audience (e.g., letting them know that they can do the recommended behavior, or telling them that the behavior will be beneficial) are more effective than messages with only the fear factor and no recommendations. An example of a message we would send to participants in the intervention study is: “Research shows that between 50% and 90% of people who work at a computer screen experience digital eye strain. Let’s take care of our eyes by taking 30 seconds to look out the window, or at anything other than a screen! Maybe you’ll notice something new.” Similar to Idea #1, this focuses on small action items. Because the baseline study found that people do not like to be disturbed during their workflows, it makes sense to minimize the amount of effort needed or disruption caused by the recommended action. Moreover, this approach incorporates elements of positivity in addition to the fear appeal, which participants noted in the baseline study to be effective.

We designed our intervention with the goal of answering the following questions:

- To what extent can fear appeals be used to motivate users to take action towards taking breaks from their work?

- What are users’ preferences in terms of frequency of notifications and timing of notifications?

To investigate these questions, we will recruit 8 participants (4 old and 4 new), again a mix of students and workers. Every day, we will send them text messages at 3 different times in the day. Participants will be asked to log how the notification made them feel, what actions they took after receiving the notification, why they did/did not listen to the reminder, and how doing/not doing the action made them feel.

Comments

Comments are closed.