Problem Domain

As a team of college students, we noticed that we all struggled with spending hours at a time doing homework and studying at our computers, as well as related issues like poor posture and burnout. When reflecting on our daily routines, our personal experiences motivated us to explore how to encourage people to take more breaks from doing work. This led us to the following problem domain: college students and young professionals need a way to ameliorate or prevent physical pain and mental health issues associated with doing work for prolonged periods of time without taking breaks. Ultimately, we are interested in how to successfully encourage these users to take more breaks during their work sessions.

Baseline Study

Methodology

Our target audience is college students and young professionals whose work involves using computers for long periods of time (e.g., office jobs). This includes those who experience pain and those who do not experience pain, as we want this intervention to also serve as a prevention effort. In concordance, we conducted screeners with 8 people, who we all identified to be a part of that target audience. Although all participants passed the screener, we chose the final 5 participants based on criteria to ensure a diverse and representative sample in terms of status (i.e., an even mix of college students and young professionals), gender, ethnicity, and occupation.

With our pre-study interviews, we hoped to gain an understanding of what people’s work sessions are like and what does and does not motivate them to take breaks during their work. We also sought to understand what makes people ignore or respond to notification reminders.

Our baseline study involved participants logging their behavior during and after their work sessions (a period of time where the participant is primarily doing work on their computer) for 5 days. We had them log:

- How long their work session lasted/how long they spent on their device

- How many breaks they took during the work session

- If they did take break(s), how long the break(s) lasted and what they did during the break(s)

- If they felt any pain or discomfort during the session; if so, where the pain or discomfort occurred

Synthesis

Affinity mapping our data revealed the following key insights:

- Although people express a desire to take more breaks during work sessions, physical breaks are laborious and rarely taken, relative to phone breaks.

- People prioritize their work sessions, such that they do not like disruptions to their work flow.

- People are generally not responsive to reminder notifications, especially when the action item is large, but positivity/encouragement in the notification can help.

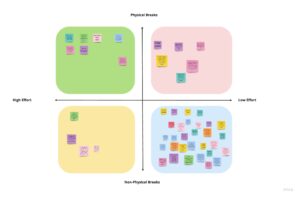

We also created the following 2×2 matrix based on the amount of effort participants’ breaks took and the physicality of their beaks. We categorized each break description into one of the quadrants.

From this matrix, we noticed that the vast majority of participants’ breaks involved low effort, non-physical breaks, such as going on social media. This matrix and insights from the interviews indicated that people are not very responsive to doing large action items. We moved forward accordingly with a focus on low effort, physical breaks for our intervention, deciding to encourage users to do simple but effective physical actions. We also incorporated positive messages in our reminders as a result of these insights.

Comparative Analysis

To better understand behavior interventions in this problem space and inform the design of our intervention, we examined strengths and weaknesses of 8 existing solutions across different mediums targeted at increasing break-taking behavior, as well as general mindfulness products.

Many comparators allowed users to take breaks through mindfulness, stretching, or affirmations. Among the solutions researched, we found that the Awareness Timer macOS app integrates into users’ workflows without interrupting it. Similarly, the StretchMinder mobile app offers “bite-size” and work-friendly exercises that can be integrated into people’s daily workflows.

A prevalent weakness we observed is the oversimplification of the break-taking process, as seen in the Take a Break Chrome extension and the Apple Watch stand reminder, raising the question of how to effectively capture users’ attention and maintain user engagement. Conversely, another weakness seen in the Finch and Time Out apps is that their abundance of features and options can be overwhelming for users.

We mapped these comparators onto a 2×2 matrix based on the disruption caused by the app and the effort required from users.

This matrix allowed us to narrow our focus to the low effort, low disruption quadrant, as our goal is to create a product that streamlines the break-taking process by seamlessly integrating into users’ existing workflows with manageable, realistic actions.

Read a more in-depth comparative analysis here.

Literature Review

We also dove into research on reducing sedentary behavior. We found several pieces of evidence demonstrating the success of prompting software and persuasive mobile apps.

One insight influencing our product development is the effectiveness of an intervention combining education with a break prompting software on reducing long sitting periods at work. Another insight is the concept of incorporating non-purposeful movement breaks at work, such as reminding users to go to the bathroom. Our literature review provided insights on how notifications can be leveraged in various intervention techniques aimed at increasing movement in the workplace. In line with these insights, we aimed for our intervention to prompt participants to take more breaks and engage in both purposeful and non-purposeful action, while also educating them about the importance of reducing sedentary behavior.

Read our full literature review here.

Personas and Journey Maps

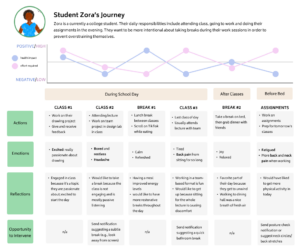

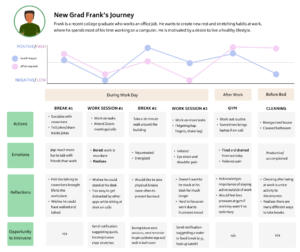

Utilizing insights from our baseline study, we created two personas—Student Zora and New Grad Frank—that highlight the behaviors and traits observed in our study participants.

From Student Zora’s journey map, we learned that their main goal is to reduce their pain by taking more breaks from using their computer, but Zora struggles with a busy schedule and does not like disruptions to their workflow.

From New Grad Frank’s journey map, we learned that his main goal is to take care of his body to prevent pain. However, he has difficulty finding opportunities to take breaks at work without embarrassing himself.

Check out the Figma to see each persona and journey map up close.

Intervention/Product Ideation

We then used these personas and journey maps to do some time mapping in order to identify intervention opportunities.

We then used our time map to create a connection circle showing the cause and effect relationships between different behaviors/habits.

Based on these methods, we came up with 3 intervention ideas:

-

Reminders for small action items: send neutral reminders for users to take a break, with a focus on realistic and achievable actions

- Pros: Because many of our users work in public spaces, recommending small actions is more achievable for users.

- Cons: People tend to ignore notifications and it is difficult to send reminders without being disruptive.

-

Fear/hope messages: send reminders that combine 1) information about the harms of prolonged sedentary behavior, and 2) a recommended action to provide hope

- Pros: People are also more likely to react to a notification that instills a sense of urgency using fear appeals.

- Cons: Too much fear can inhibit someone from taking action and can cause a negative reaction.

-

Every time participants get an email, they should check/fix their posture, roll shoulders, or do a small stretch

- Pros: If successful, participants would build habits all on their own. This is also a very straightforward study.

- Cons: Participants are responsible for remembering the rule, making it difficult to track effectiveness without reminders from researchers.

After reviewing our options, we decided to implement the fear/hope messages intervention. Our rationale for choosing this is rooted in psychological research on fear appeals (Tannenbaum et al., 2015). Research shows that fear appeals are most effective when moderate amounts of fear are present, and when they are paired with recommended actions for the audience.

View our detailed baseline study synthesis process and intervention ideation here.

Intervention Study

We designed our intervention with the goal of answering the following questions:

- To what extent can fear appeals be used to motivate users to take action towards taking breaks from their work?

- What are users’ preferences in terms of frequency of notifications and timing of notifications?

We recruited 8 participants through personal connections, including 4 participants from the baseline study and 4 new participants with a mix of students and workers. These participants were a part of our target audience, which is the same as the baseline study. We enacted a notification-based system, where we sent participants 3 text messages throughout the day for 5 days. These messages began with a statement about a negative effect of a behavior related to not taking enough breaks (e.g., sedentary behavior), followed by enthusiastic suggested action items to counteract/prevent these effects. Participants were asked to log how the notification made them feel, what actions they took after receiving the notification, why they did/did not listen to the reminder, and how doing/not doing the action made them feel. The photos below show examples of messages:

After data collection, we synthesized our results through affinity mapping.

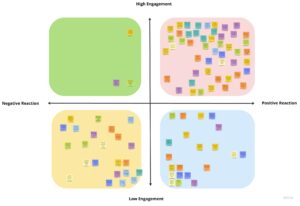

We also created a 2×2 matrix, categorizing users’ actions based on their level of engagement with our notification and whether their reaction was positive or negative.

A connection circle was also created to represent the observed trends:

Our synthesis yielded these key insights:

- Participants saw and felt benefits and positive impacts of following the suggested actions in the reminders (e.g., feeling more energetic, awake, relaxed).

- Reminders made participants more aware of their habits and health, and participants mostly felt positively about the reminders.

- Some participants felt motivated to do the recommendations because the reminders came from a friend (us).

We also saw some tensions and contradictions:

- Sometimes, users are in situations where they cannot engage (e.g., in a meeting), but some participants adapted recommended actions to be more suitable to their situation.

- Some participants became less receptive to the reminders towards the end of the study.

- The fear factor was too strong in a couple of messages.

These insights pose several implications for our project. Because the fear/hope reminders were successful in increasing break-taking behavior, we plan to continue with this concept at the core of our product design. The insights also highlight the potential of social accountability to increase break-taking behavior during work sessions, so we may incorporate a social element in our product allowing friends to remind each other. We also intend to address the tensions and contradictions identified. Based on the plateau effect observed, we plan to reduce the frequency of messages to retain engagement. We also must find a way to accommodate users when they are in situations where they can’t adhere to the reminders—perhaps this could involve users inputting their schedule, or implementing a snooze/”remind me again in 10 minutes” feature. Finally, we will revisit/refine our messages to ensure that there is no triggering or excessively alarming content (e.g., not mentioning death or severe illnesses).

Storyboard

From the personas and journey maps, we created a storyboard that follows Frank (not to be confused with New Grad Frank—this is a different character) as he tries to get up more and take more breaks at work.

From this storyboard, we learned that user-initiated efforts to change their own behavior are not the most effective. This story demonstrates that an external force, or push, was necessary to promote action. This storyboard shows how our product would serve as a source of constant reminders for Frank to take breaks from his work by providing various small actions as stepping blocks towards taking better care of his health.

Current Direction and Feedback

Given that our intervention study participants completed the majority of the recommended actions and reported positive reactions after doing them, we plan to design a browser extension or desktop application with semi-scheduled reminders combining the elements of fear and hope to encourage users to take breaks from their work to tend to their bodily needs.

However, we are brainstorming how to prevent users from plateauing in their behavior change, as well as how to prevent users from becoming irritated with the notifications. We are also discussing users potentially becoming desensitized to fear appeals. Thus, we would appreciate feedback or thoughts on these aspects.