Final Writeup

CS 247B : Design for Behavior Change

Winter 2022

Cat Davis, Kara Eng, Nic Machado, Alejo Navarro, Pablo Ocampo

Christina Wodtke

Problem Finding

As we came back to campus and started reconnecting with people, we have been surprised by how monotonous and repetitive a lot of our conversations have been. We wanted to find a way to break from our same everyday conversations and form more meaningful connections.

Literature Review (link)

We found that conversation starters stimulate deeper conversations by pushing people out of their comfort zone. That said, it is important to keep the dialogue spontaneous and avoid interactions feeling like an interview or monologue. Although it is important to curate conversations to the comfort level of those involved, people tend to overestimate how awkward deep conversations will be.

Comparative Research (link)

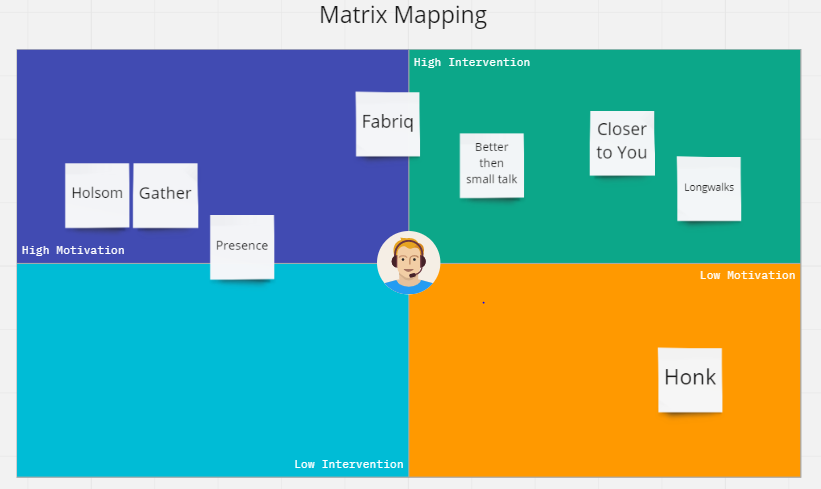

Given the pervasiveness of our problem, we found several existing solution attempts. We decided to plot these based on their degree of intervention and motivation. The results are presented below.

2×2

Most current solutions, such as Fabriq and Longwalks, present users with a bank of questions to choose from, often divided by categories. Some are aimed at couples forming deep relationships and others at enhancing casual conversations. However, we found no solution had any habit forming components; they were focused on one-off interactions. Additionally, there was no ability to cater questions to the level of relationship (other than shying away from some categories) or the ability to reflect on the conversation experience.

Baseline Study (link)

Our hypothesis was that people were not regularly participating in deep conversations. So, we asked participants to look back at all the social interactions they remembered (each day) and reflect on how deep they were. We found that most people struggled to break from their routine and were stuck having the same superficial conversations over and over. Interestingly, many participants reported feeling their social skills had deteriorated with the pandemic.

Personas (link)

In our exploration, we found two main personas to design for: Frankie-the-Freshman and Post-Pandemic-Penelope. Frankie-the-Freshman is eager to make new friends but is having a hard time moving beyond superficial conversations. Post-Pandemic-Penelope on the other hand is reconnecting with friends she has not interacted with in a while because of the pandemic and general social isolation. For different reasons, both of our personas have the motivation but lack the means to consistently connect on a deeper level.

Solution Finding

Intervention Study (link)

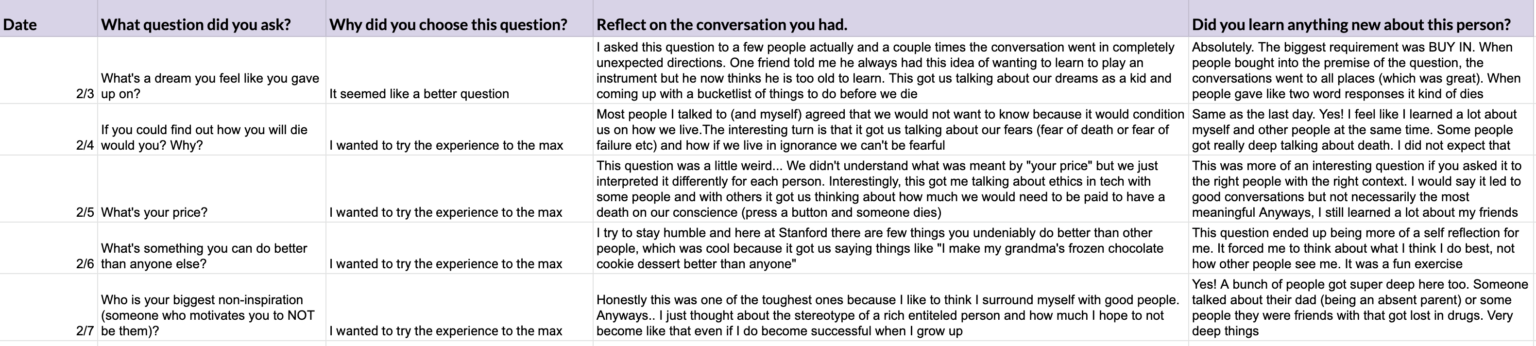

Based on our earlier findings, we wanted to put the notion that conversation starters can create deeper conversations to the test. We also wanted to incorporate our earlier insights that deep questions are not suitable for all conversation partners and that creating habits is an effective means of behavior change. Our synthesized solution was an intervention study asking participants to choose between two questions each day to ask their friends and people they meet. We conducted this study on six people over a five day period. Each day, participants were sent both a casual question and a deep question via text. They were asked to use the questions to start conversations throughout the day, giving the flexibility to choose the most appropriate question for each interaction. They were then asked to reflect on their experiences by logging details about their conversations and noting if their conversations taught them anything new about their conversation partner in a Google sheet (example log pictured below).

Example Reflection Log (all logs)

Through our intervention study, we found that participants’ previously-existing comfort level with their conversation partner influenced how vulnerable their conversations were. Having the flexibility of deep and casual questions, in these cases, allowed for participants to have especially meaningful conversations when they asked people they already knew the deeper question. Additionally, we found that, as the study progressed, participants found it easier to remember to ask the questions and reflect on their conversations in their logs. This finding showed us that the cadence of releasing new questions daily helped people develop the habit of asking our questions. Overall, using questions as a form of conversation starter seemed to be successful in catalyzing meaningful conversations. Questions that led people to share different opinions were noted as particularly successful, as they led to meaningful, sometimes intense, debates.

If we were to conduct this study again, we would release the questions and allow for reflection in the same place. We found that, throughout the study, participants would forget to fill out their logs. While all participants expressed that they successfully asked the questions, many noted that they would forget to log their reflections entirely or would log them at the end of the day, at which point it was hard to remember the specifics of each, unique conversation. In order to make the reflection process more convenient, we would store the questions and log in the same place so that, when participants pull up the question to ask it in conversation, the log is already open for them to fill in. By making this process easier for the participants, we would be able to get more accurate data in the reflections, and, as a result, we could better gauge how successful our questions were in stimulating meaningful conversations.

Mapping (link)

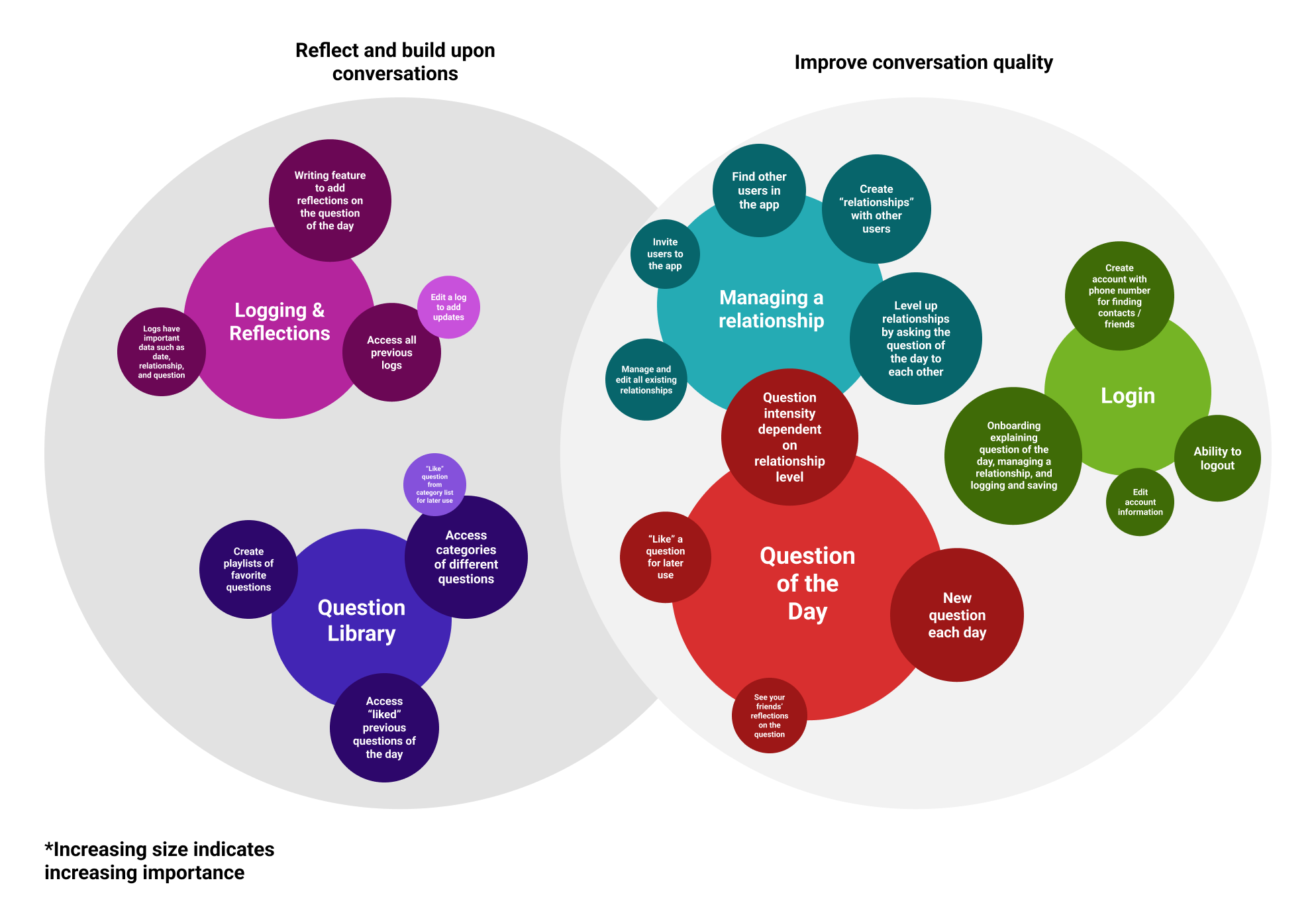

Bubble Map

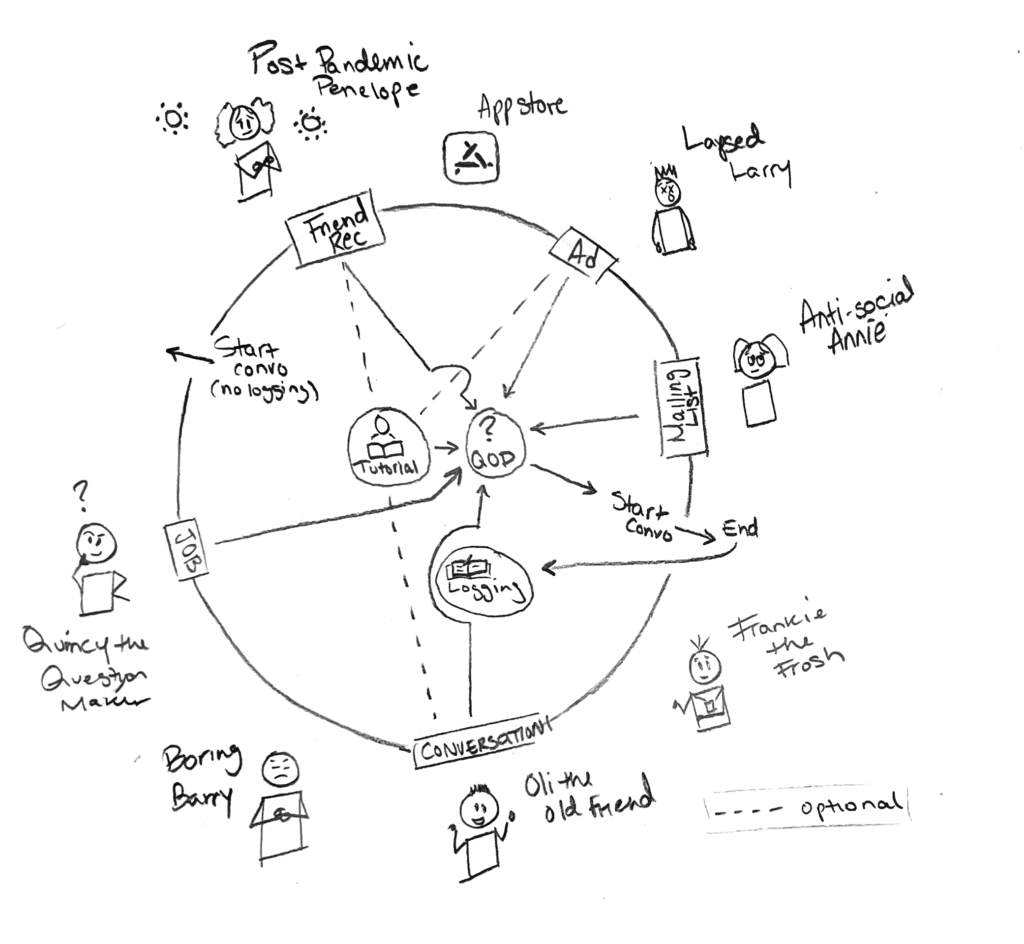

System Path Diagram

The two maps we drew most insights from were the Bubble Maps and System Path Diagrams. The Bubble Map allowed us to visualize the strength of intercontednecess between key features. Through visualizing the distance and sizes of the bubbles, we learned that there is a deep interconnection between Question of the Day and Relationship Level, and Question of the Day takes priority over the question library when optimizing habit-creation. We learned this because we noted the question category bubble was most distanced from the rest of the feature set. Our biggest insight from the System Path Diagram was that there exists large friction between QoD and Logging if the user leaves the app after the conversation, as in our system we mapped an arrow where the user had to leave the system and return again. This large friction point led us to conclude that there should be notification cues if the user did not log their daily question.

In all, the most helpful aspects of the mapping were the sizing and distance between bubbles to learn interconnectedness, along with drawing potential outcomes of user interactions in the system path diagram, which led to the above insights. In the future, we would use both the Bubble Map and System Path diagrams again by iterating on the same singular copy of each one, adding new features to the diagrams to learn new insights regarding interconnectedness and potential friction points.

Assumption Testing (link)

While we mapped out our assumptions, we drew heavily from our own experiences of having conversations with friends and acquaintances. However, we had three assumptions that we were unsure about yet core to our solution:

- Asking many questions isn’t annoying

- People will take the questions seriously

- People want to reflect on their conversations

Experiment Synthesis

To test these three assumptions, we ran three experiments.

In order to see whether asking many questions is annoying or not, we ran an experiment where we had a 20 minute conversation with people by asking question after question. We found that the time constraint gamified the conversation and kept the depth of conversation pretty shallow. However, having more than one participant in the discussion (besides the moderator) lowered the stakes of interactions and made the conversation less awkward.

To test whether people would take our questions seriously, we asked people meaningful questions and saw how short their answers were. While brevity does not always indicate a lack of care or thoughtfulness, we found that our participants were generally happy to elaborate on their answers when asked to explain their initial response. We also found that the prior relationship between the moderator and the participant strongly influenced the type of response; those with a more sarcastic relationship gave shorter answers.

Finally, to see whether people want to reflect on their conversations, we asked participants to reflect on their conversations during the day for 2-5 minutes without doing anything else. We observed that those participants with prior habits of reflecting on conversations were able to focus on the task more easily and those who did not have these prior habits had trouble focusing for that long.

From our experiments, we affirmed our need to allow users to customize the level of intimacy of their questions and that we needed to help some users build up to reflection.

Designing the Solution

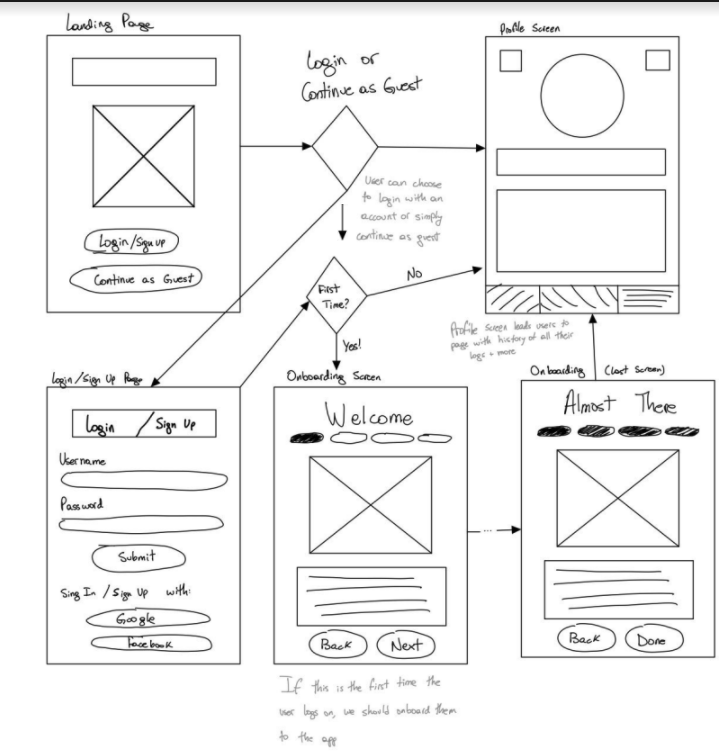

Wireflows (link to more in depth write-up on wireflows)

Example Wireflows (link to all wireflows)

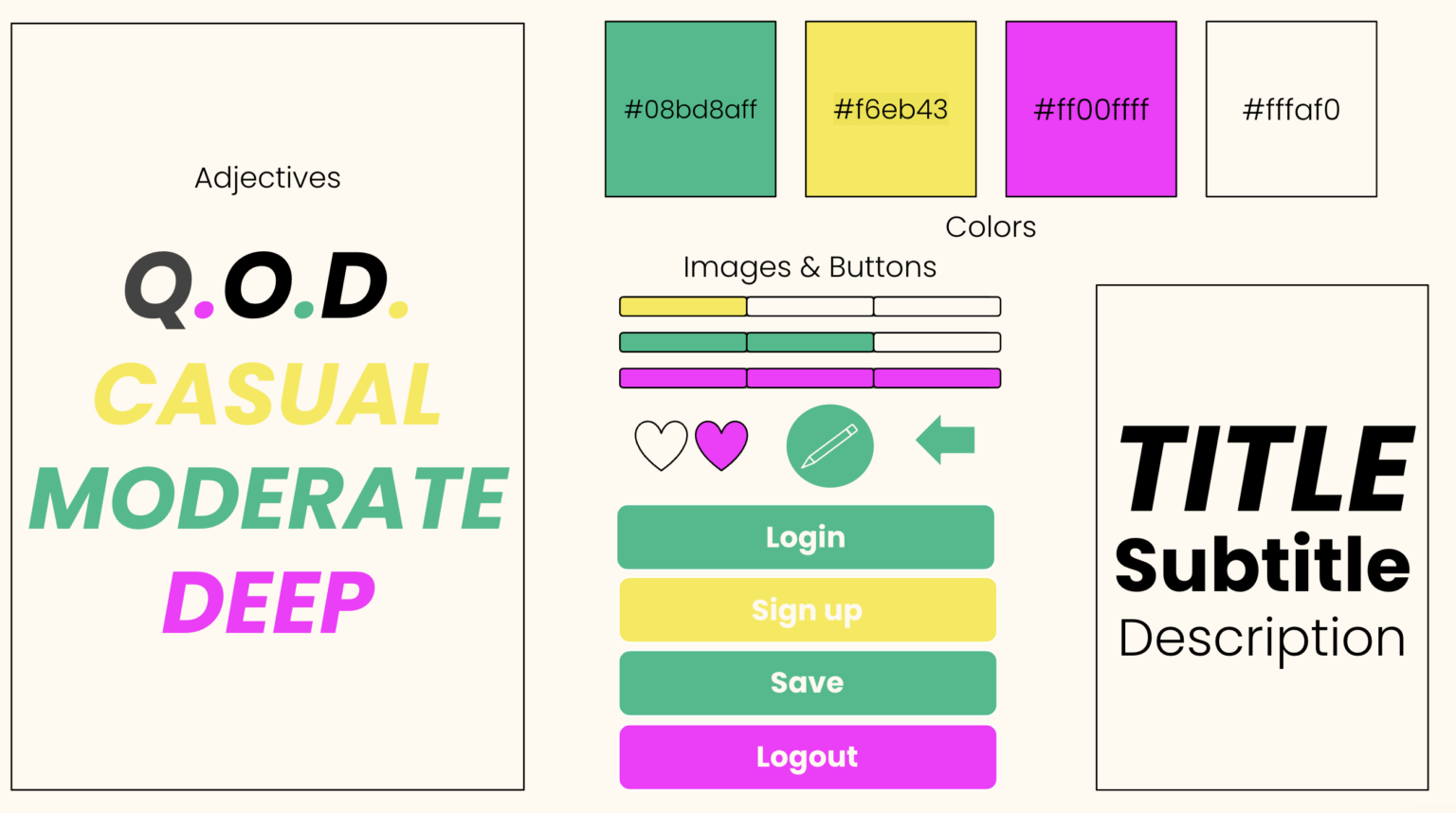

Mood Boards and Style Tiles (link)

Final Mood Board

Style Tile

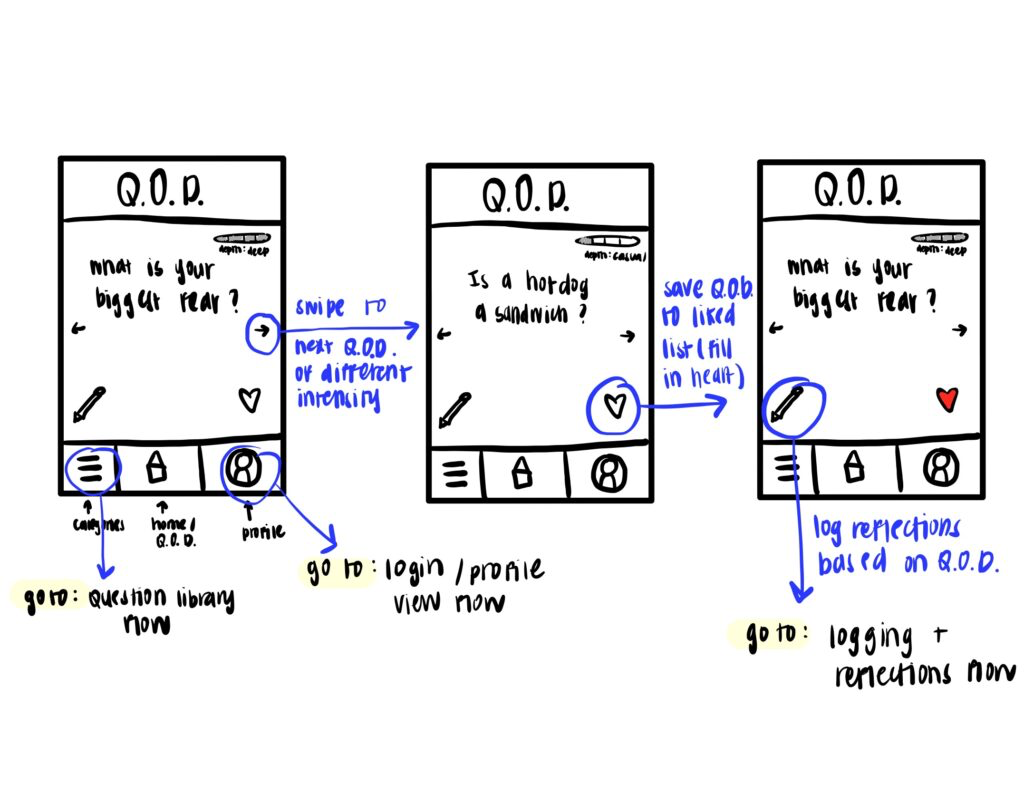

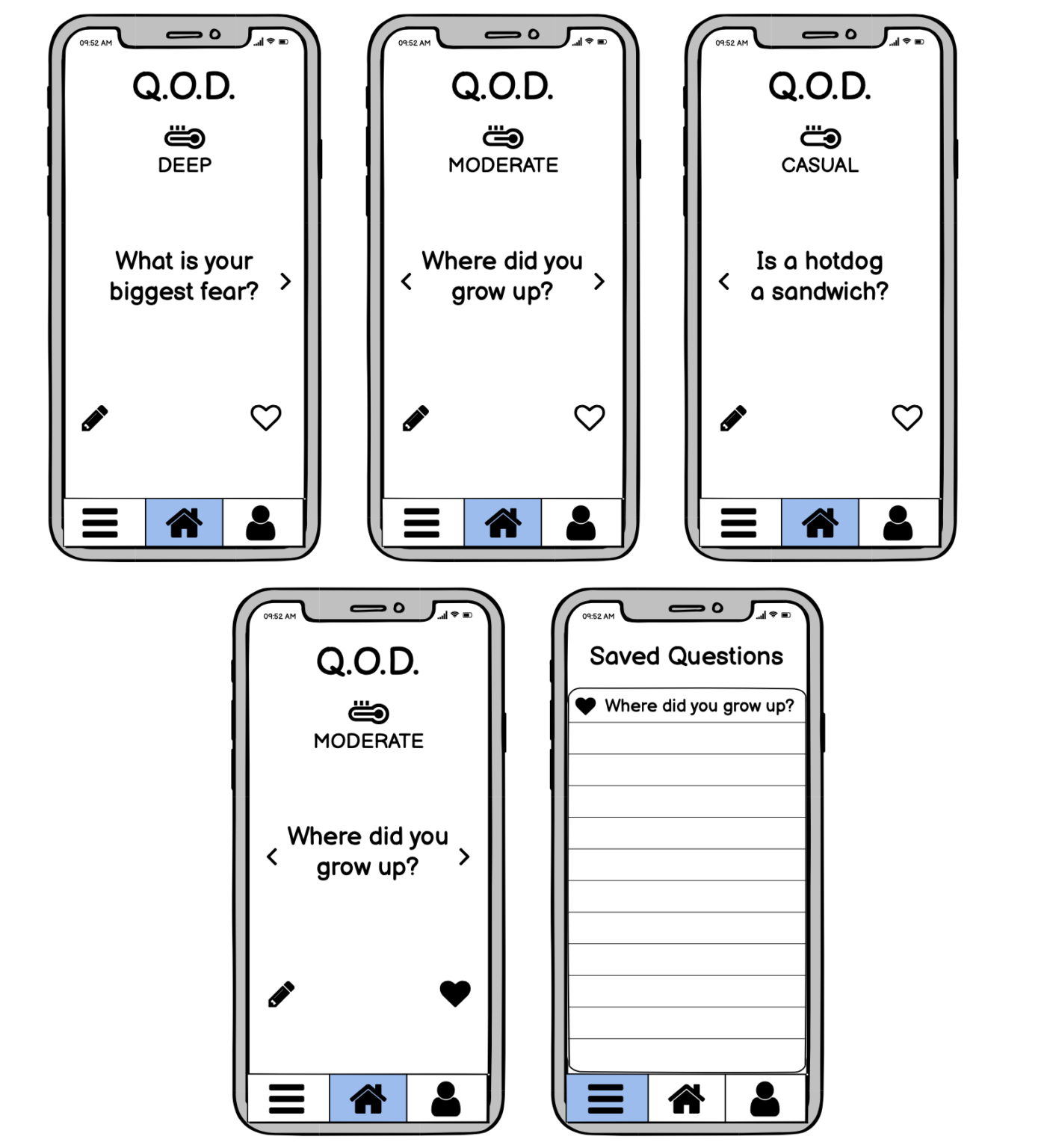

Sketchy Screens (link to more in depth write-up on sketchy screens)

Example Sketchy Screens (link to all sketchy screens)

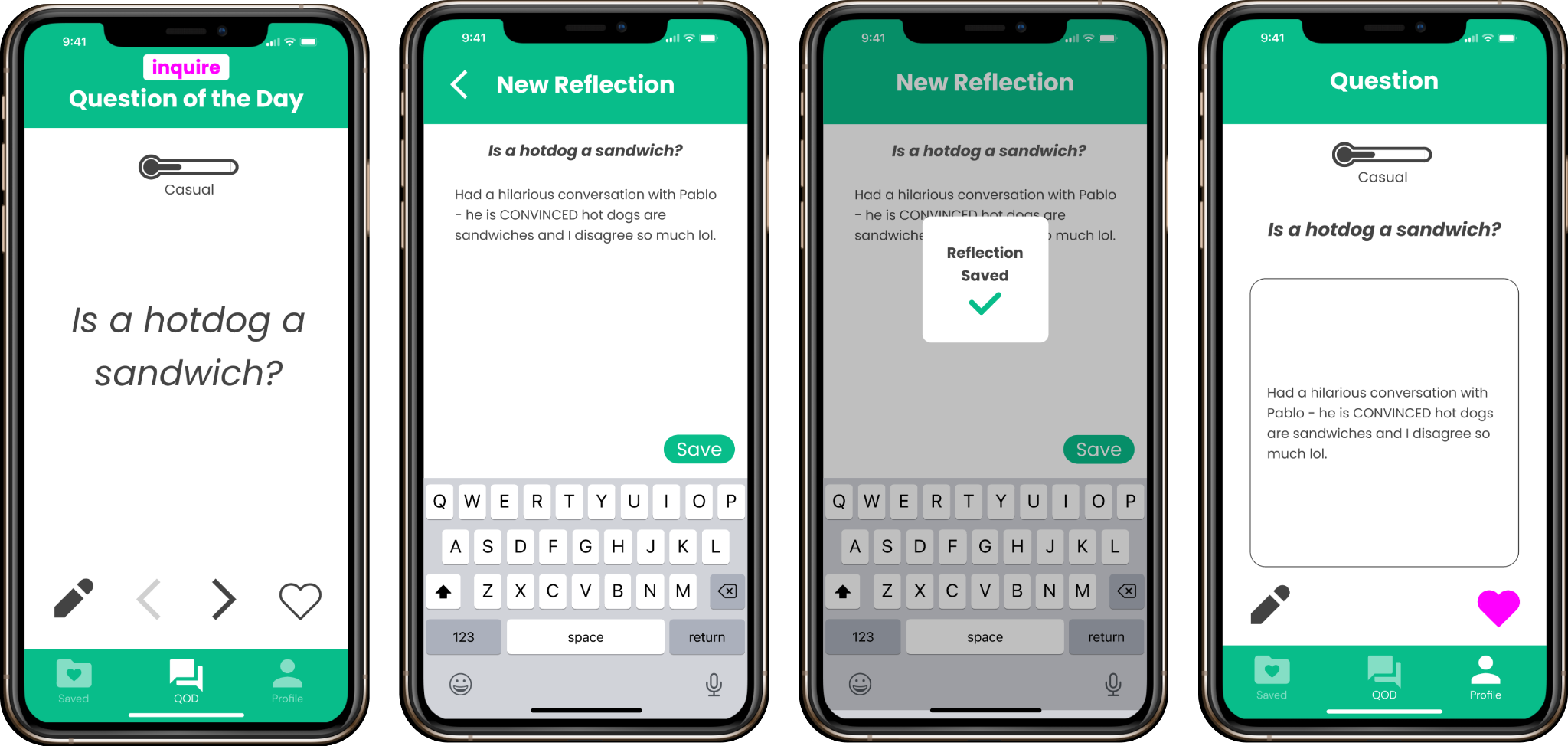

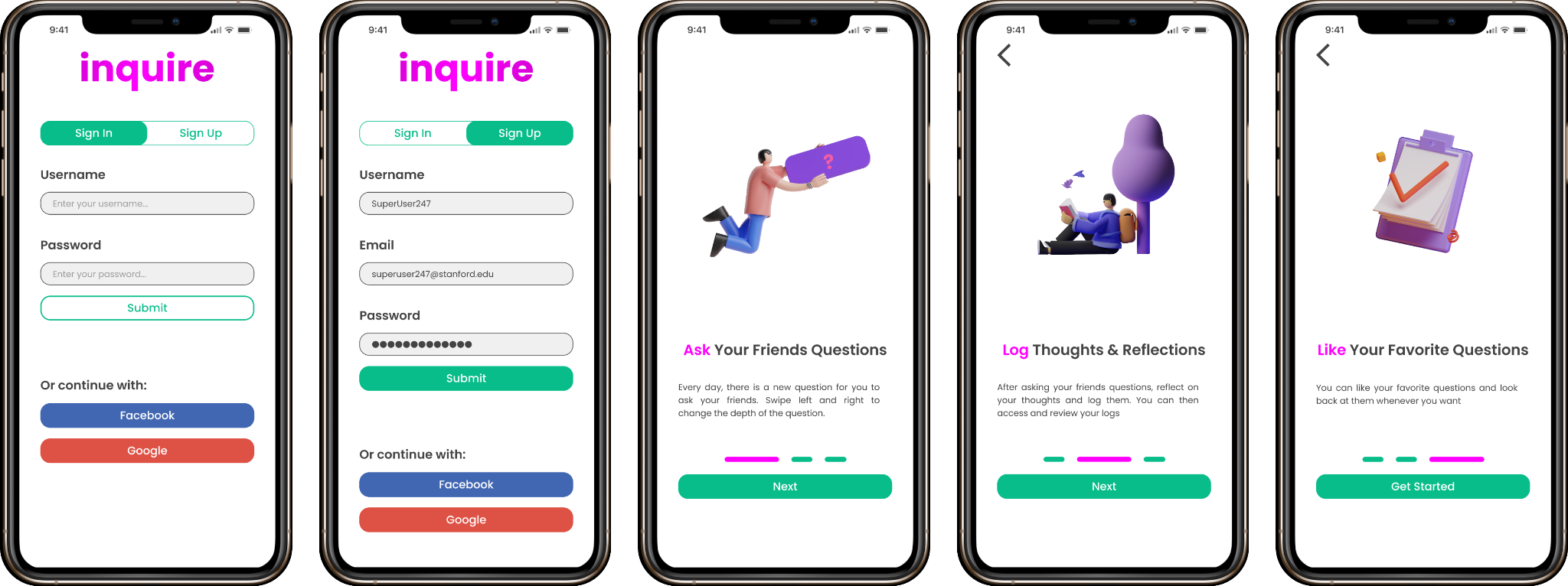

Prototype Version 1

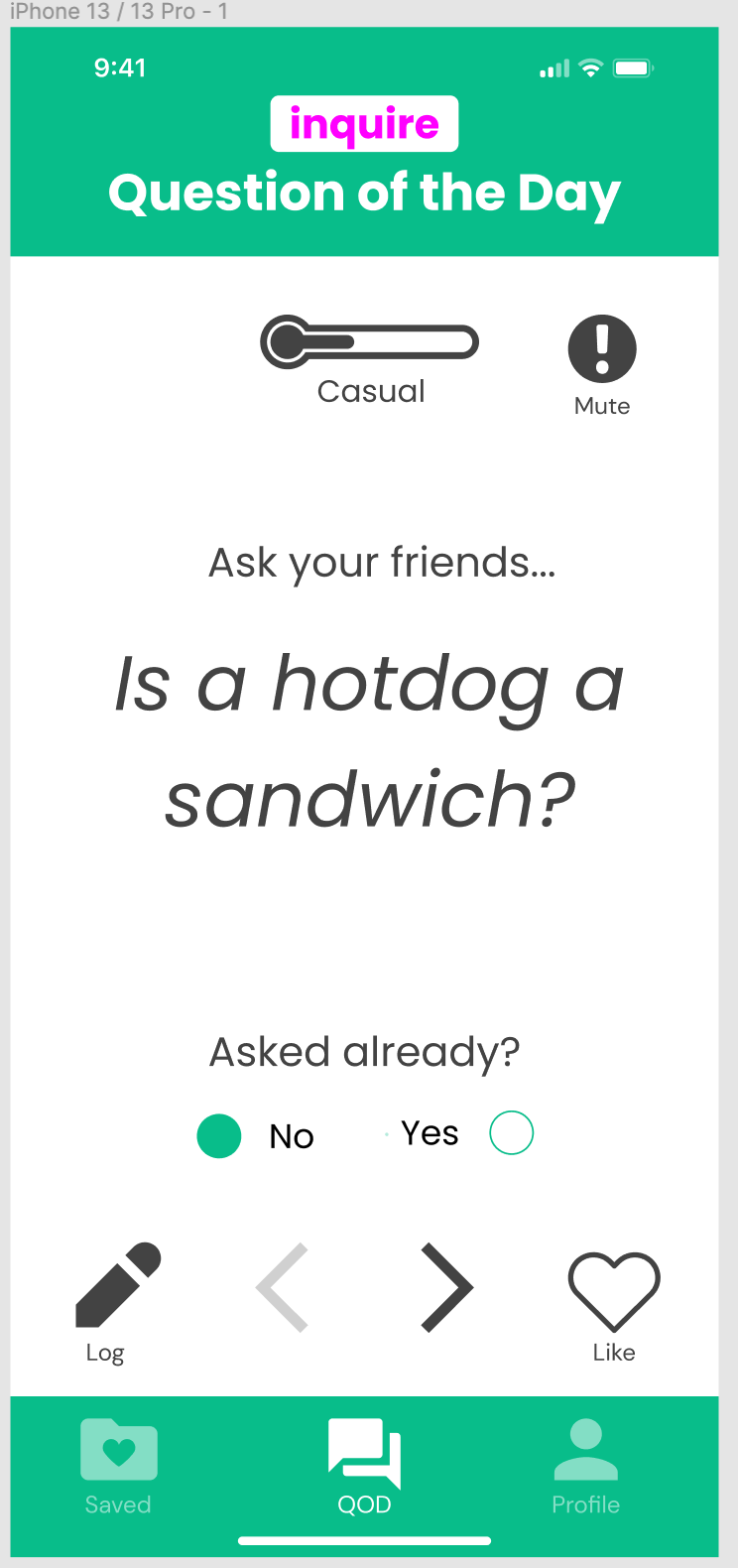

Viewing and Saving Questions

Logging a conversation

Signing-in and Onboarding

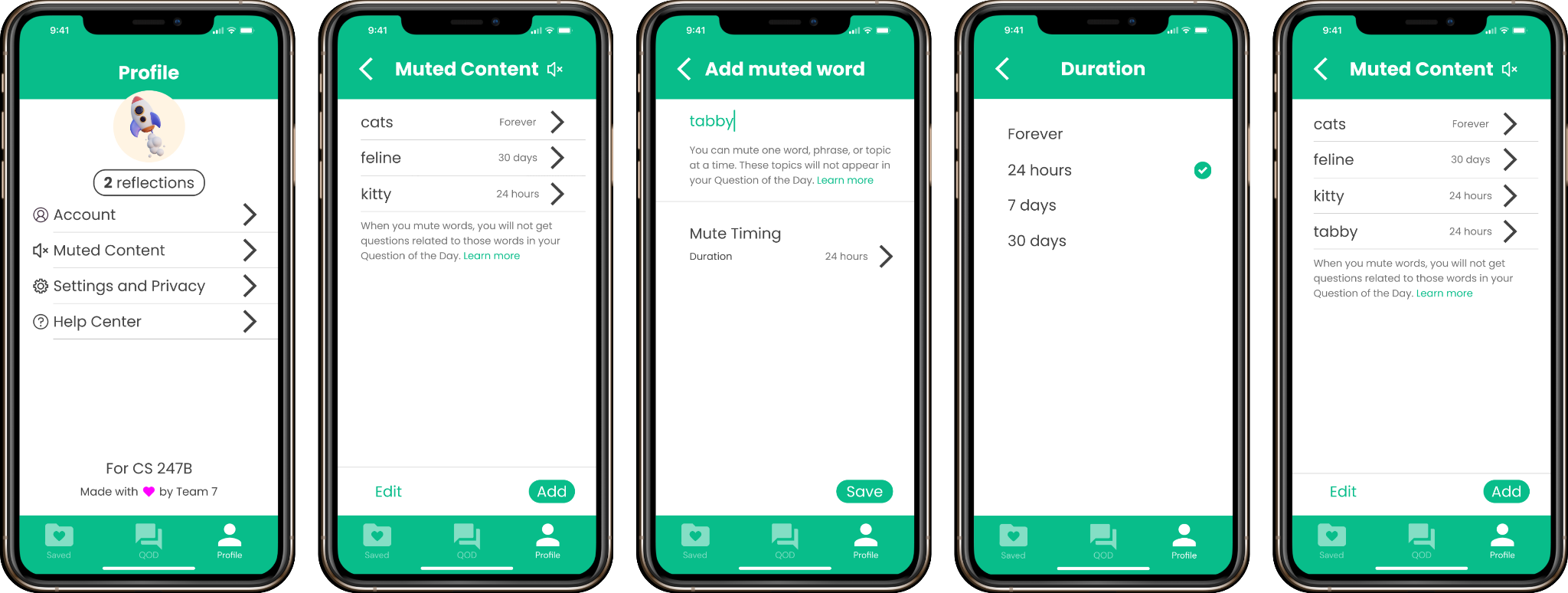

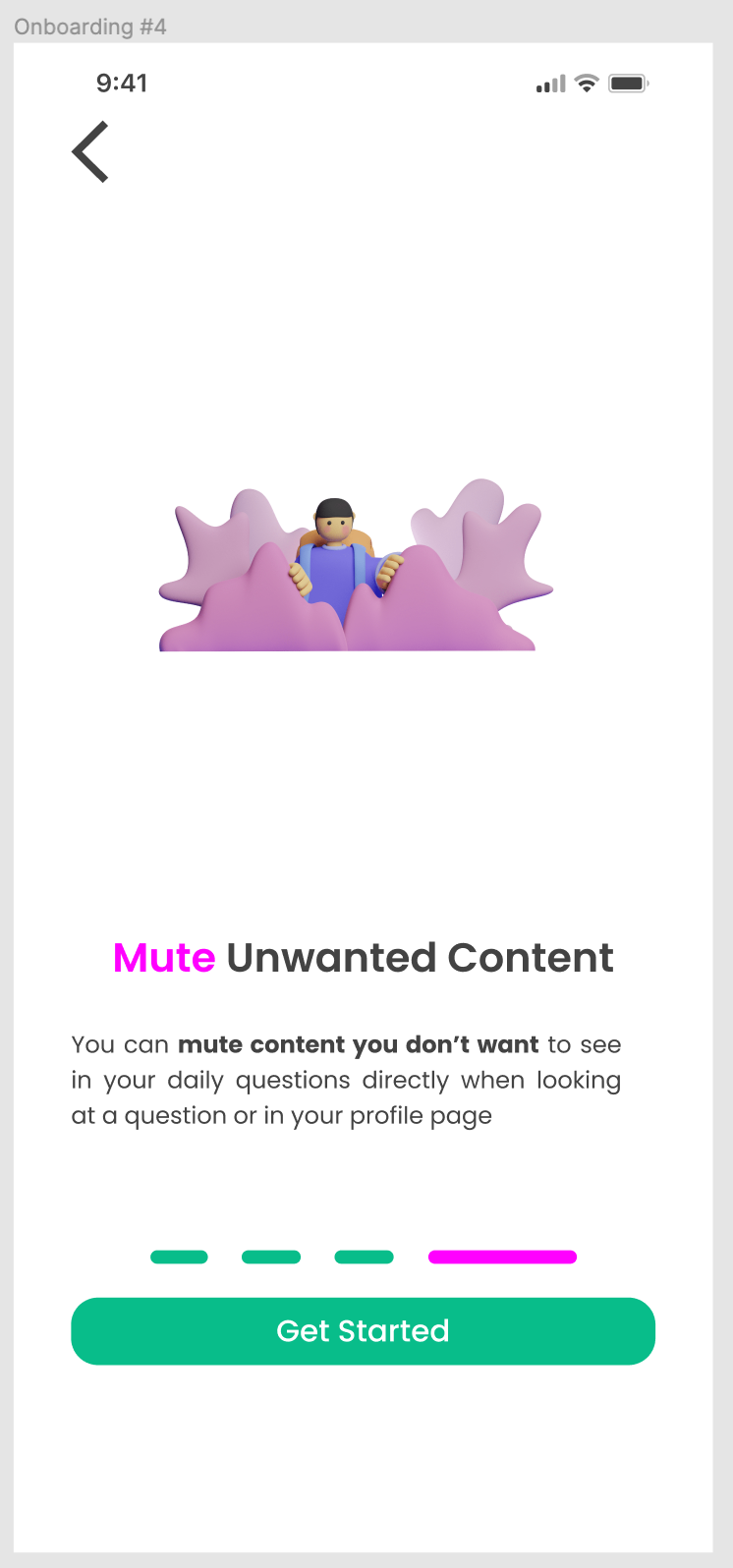

Adding Muted Content

Changes Based on Feedback

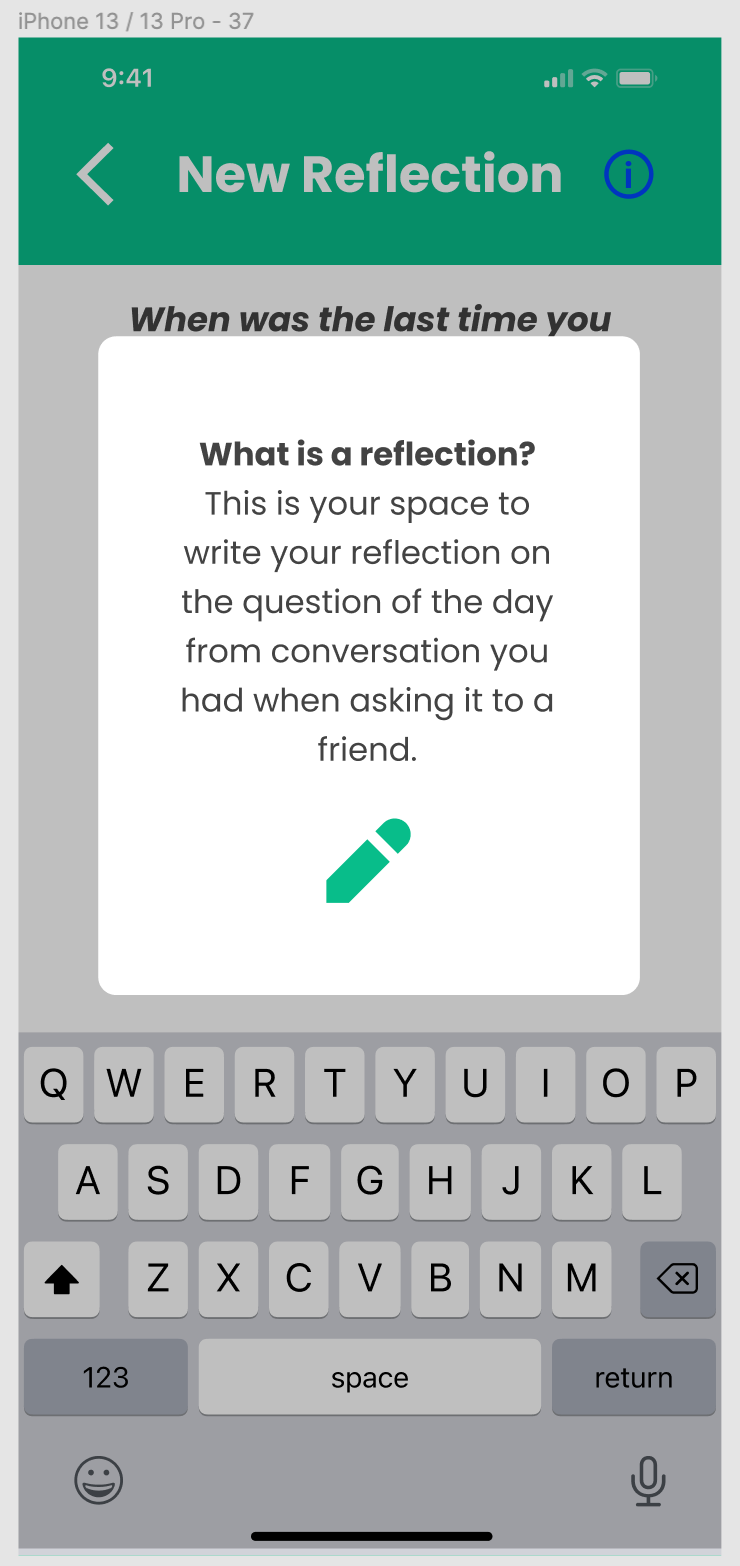

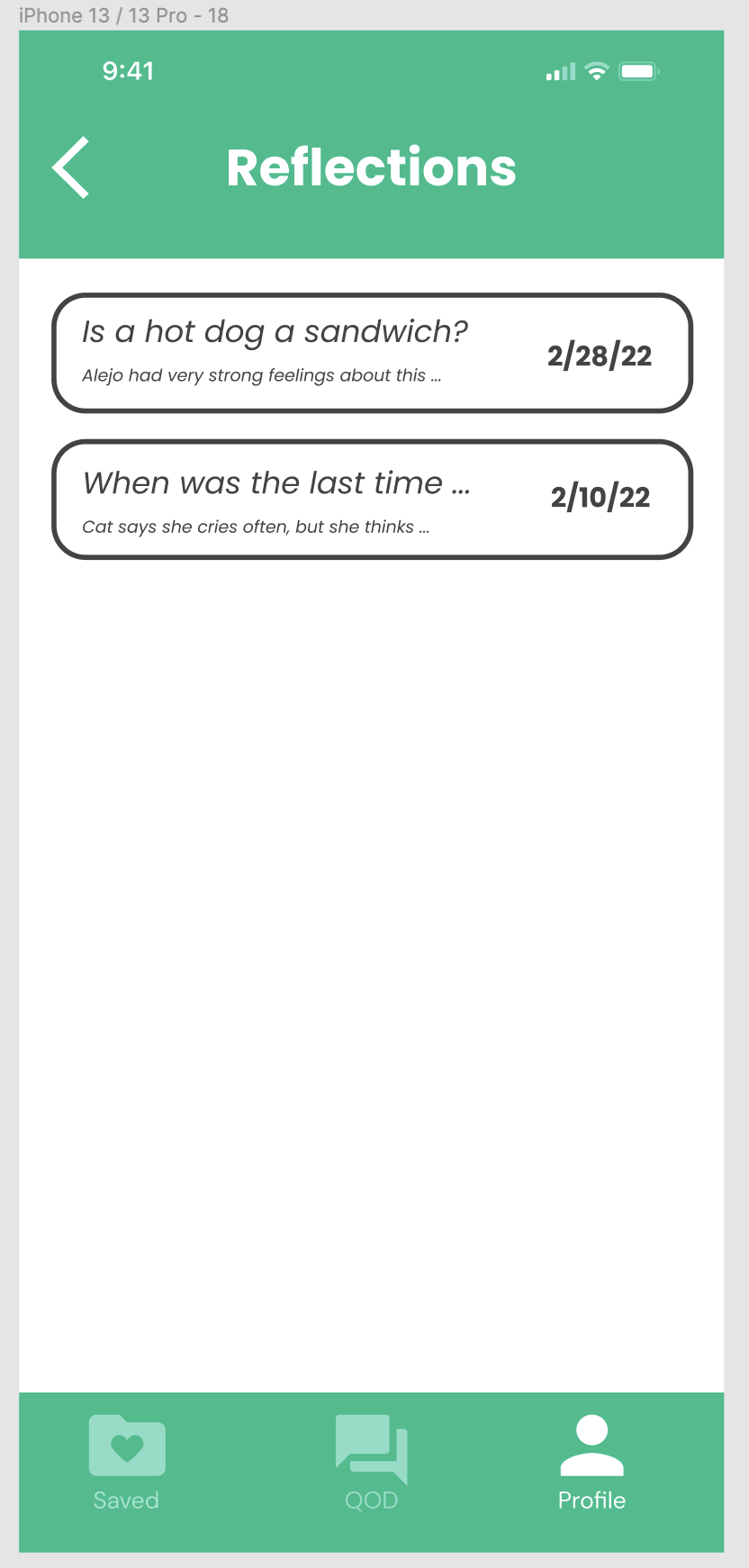

Based on final feedback points from the teaching team, we added a few tweaks to the final design. This includes a “Muted Content” explainer in the onboarding screen, the option to add muted content directly from question of the day, an “information” popup when writing a reflection to explain what is expected, reflection preview to communicate to the user that they’ve already written a response, and allowing the user to indicate explicitly if they’ve answered a question. Screenshots are shown below.

Muted Content

Reflection Help

Answer Indication

Reflection Preview

Clickable Prototype

Figma Prototype

Usability Testing/Moving Forward (link)

Three of the main issues that we found with our prototype were (1) Despite the onboarding, users were not sure what they were supposed to do with the question of the day on the main screen. Some thought that they were supposed to reflect on it themselves rather than talk to friends about it so we added a prompt in the main page to remind users that the question is meant as a conversation starter.

(2) Users liked the concept of flagging certain content as content that they did not want to see but did not immediately know where to flag the content. Particularly they were confused about the icon and the location of the flow. We changed the icon from a very literal speaker with an “X”, to a warning icon representing caution. Also users can immediately mute content through the main question page, instead of having to through nested settings pages.

(3) Lastly, users did not immediately understand the difference between a saved question and a reflection. To differentiate them we made sure to add a preview within the glanceable reflection chip itself of the reflection so a user knows that this is a question they have already used in conversation.

Ethical Analysis and Broader Impacts

Like any other technology or product, our project has the potential for misuse. While we cannot control who our users converse with or how they use our questions, we can at least try to build infrastructure in our project that tries to address these concerns.

Nudging and Manipulation

Although not reflected in the final prototype (due to not including home screen notification interactions), our project intends to use notifications to cue users to open their question of the day (at a frequency the user designates) along with notifying them to log their question if they opened the app. These mechanisms are acceptable because they encourage positive human interaction, and discourages interaction with the phone. For users who are anxious about their friendships, these cues may become manipulative because it will likely push them to use the app even if it increases their anxiety. We hope to mitigate these cases by having the default state of no notifications.

Privacy

Our largest privacy concern is that our user logs may contain private or sensitive personal information and thoughts. We directly address this by making our definition of privacy very clear during onboarding: that user information will be completely encrypted and anonymized, and that Inquire will never share user data. A future development that may compromise user privacy is if executives want to use the users’ logs to train recommendation AI models for better questions, or if a company wants to acquire our data. These developments can be avoided by making the product / company culture very clear that privacy is priority, so executives and acquirers would understand this is not a budging point.

Interface Design & Design Justice

We chose to keep our app’s interface as simple as possible. We want users to be able to jump into our app immediately. We incorporated white space wherever we could so that users would not be overwhelmed with information. While our chosen color palette might not be the most accessible to the colorblind, there are no parts of the design that require that users know which color is which.

Design for Well-Being

Our app is intended to promote self reflection and more meaningful connection with others. By providing the questions and the space to reflect on them, we hope that users can become more self-aware and thoughtful about their interactions with others. However, our app might put undue pressure on those with social anxiety; they might feel obligated to ask people questions when they’re not comfortable.

Broader Impacts

If this app is widely adopted in its behavior change, we believe it would have a large positive broader impact on society. In short, humans would have more meaningful conversations and grow stronger bonds through conversations.

Conclusion

As a group, we found that designing for behavior change is a much more complicated task than one might expect, but, working in a relatively large team of five people allowed us to utilize our own unique experiences to help curate our design solution. Specifically, we found that one major benefit of working in a group with five people was that having more eyes on our project as it developed allowed us to be more aware of ethical concerns. Because so many of us were involved in every step of the design process, we were able to catch more ethical and/or accessibility concerns than any single one of us would have if we were working alone. In this way, our individual experiences and concerns were an asset throughout the design process. In our future behavior design efforts, we intend to seek out large, diverse teams in order to utilize unique perspectives.