Problem Finding

When Team 9 was brainstorming problem spaces to tackle, we came up with a diverse, vast set of ideas, and the main patterns that emerged upon our selection were that we wanted to incorporate some sort of wellness component, reflection component, and novelty of experiences component. We also thought critically about how society had drastically changed over the last few years and what was left behind, deprioritized, or lacking due to the pandemic. We realized that due to increasing responsibilities, technological advances, and a shift to work from home culture, many people are spending the majority of their time indoors. Therefore, we decided to explore how to make spending time outside accessible to people, whether that means geographically, navigationally physically, or psycho-culturally.

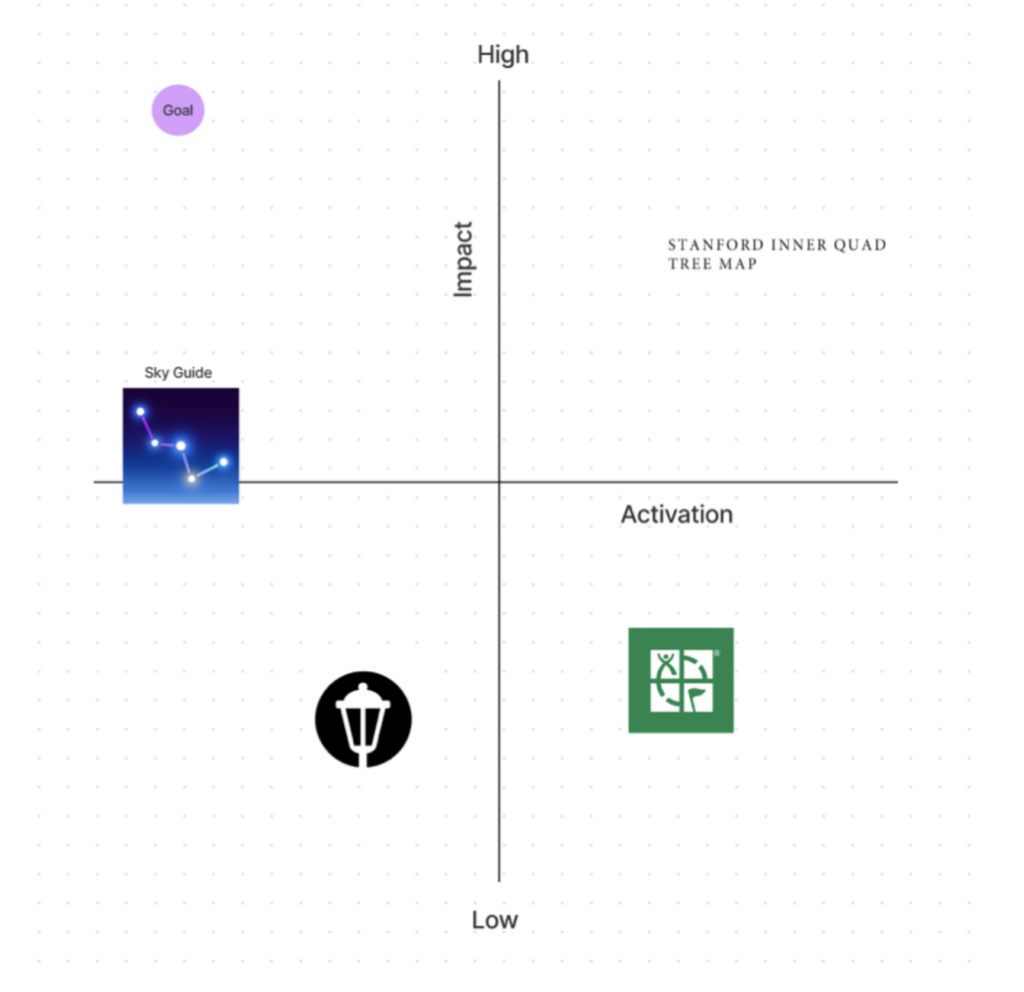

We first dove into this space by performing a literature review of the numerous benefits and barriers to spending time outside. At a high level, we learned regularly spending time outside has a significant, robust effect on emotional wellbeing, cognitive sharpness, physical fitness, and sense of social belonging, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, environmental and psycho-social factors such as physical inaccessibility, outdoor pollution, lack of safety and comfort outside due to identity acted as strong barriers that prevented people from getting outside. Recognizing this, we performed a comparator analysis of existing digital interventions in this space, mapping products ranging from gamification, community engagement, integrated reality, and education on a 2D matrix comparing the product’s impact (the influence the app had on sustained, habitual behavior change) and the product’s difficulty (the amount of activation energy and effort it takes to consistently maintain usage of the app). Highly interactive and educational applications like Stanford Tree Maps had high labor costs but strong potential for sustained user change while other low effort apps like the outdoor community forum Neighborhood which did not directly ask users to personally go outside had a smaller impact. From these insights, we sought to optimize our service to the ideal balance between low labor, high impact by incorporating elements of each service (e.g: outdoor tasks and leveraging social communities).

Baseline Study

For our baseline study, our intention was to study the different motivations for why people spend time outside, different environmental barriers people face given through geographic and socioeconomic background, and different psychosocial barriers people face given their identities and time. Therefore, we asked participants to take note of what time they go outside (change in settings), what they are doing in the moment and why (intention), where/what type of outdoor spaces they frequent (environment), how they are feeling (including how safe and energetic they feel) to naturalistically observe users’ pre-existing relationship to spending time outside. It was also critical to us for this stage to do breadth-wise exploration so we made sure to interview 9 participants that hit every positionality towards the outdoors: an urban dweller, suburban/rural dweller, nature noobie, essential worker/blue collar worker, white collar worker (remote), white collar worker (in person). At a high level, we found that while people expressed enjoying spending time outside, they had conflicting attitudes towards the outdoor due to:

- Activation energy required to leave the comfort of your home

- Viewing outdoors as something dedicated for certain activities / People want to have an intention to do some task outside

- Spending time outside seems very laborious and time consuming (and is easy to push off as a non-priority)

- Not feeling safe or comfortable to move around outside (especially at night) or in urban recreation spaces due to crime

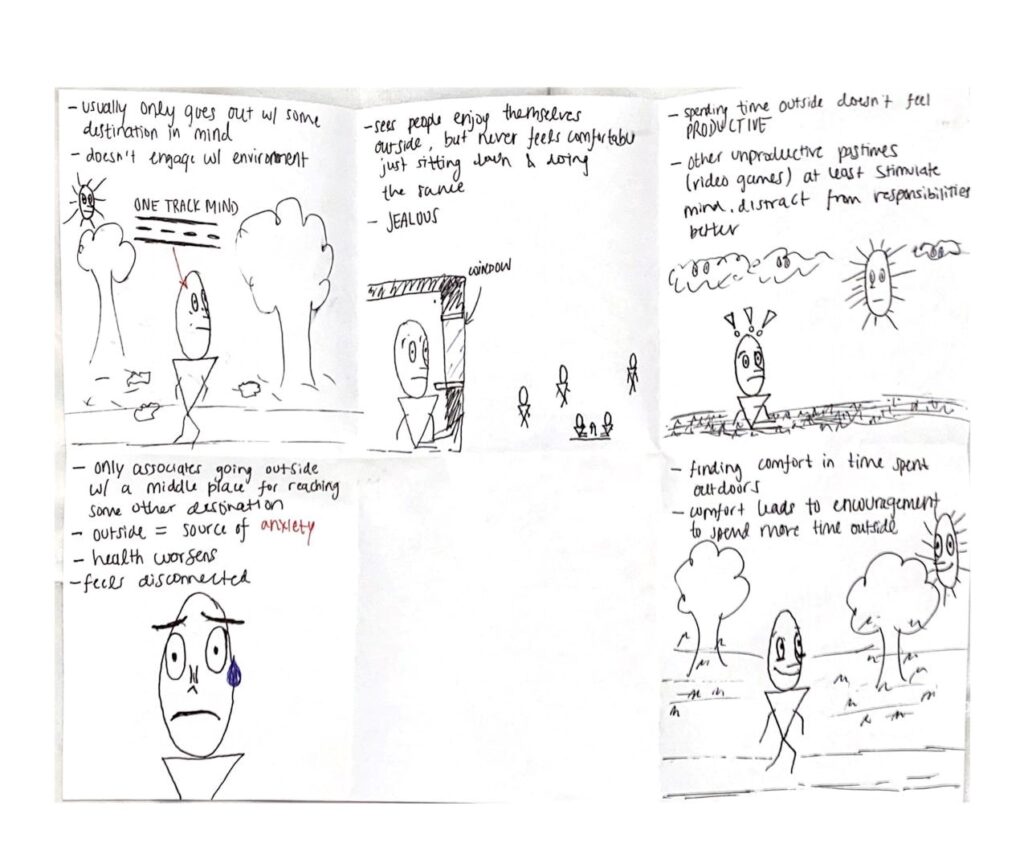

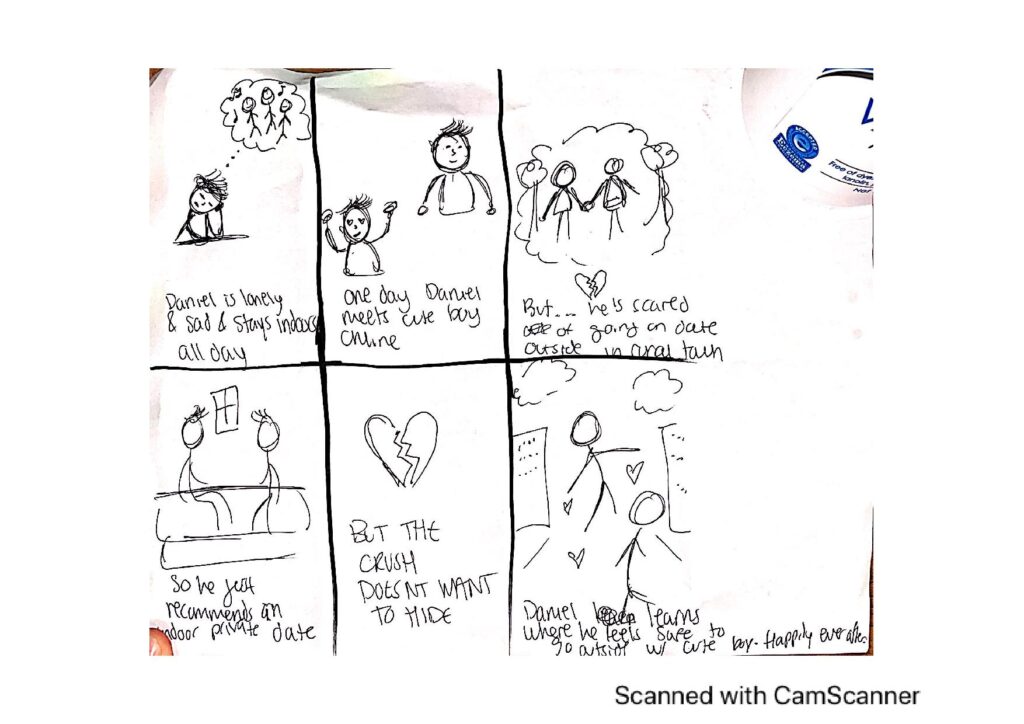

Personas, Journey Mapping, and Storyboards

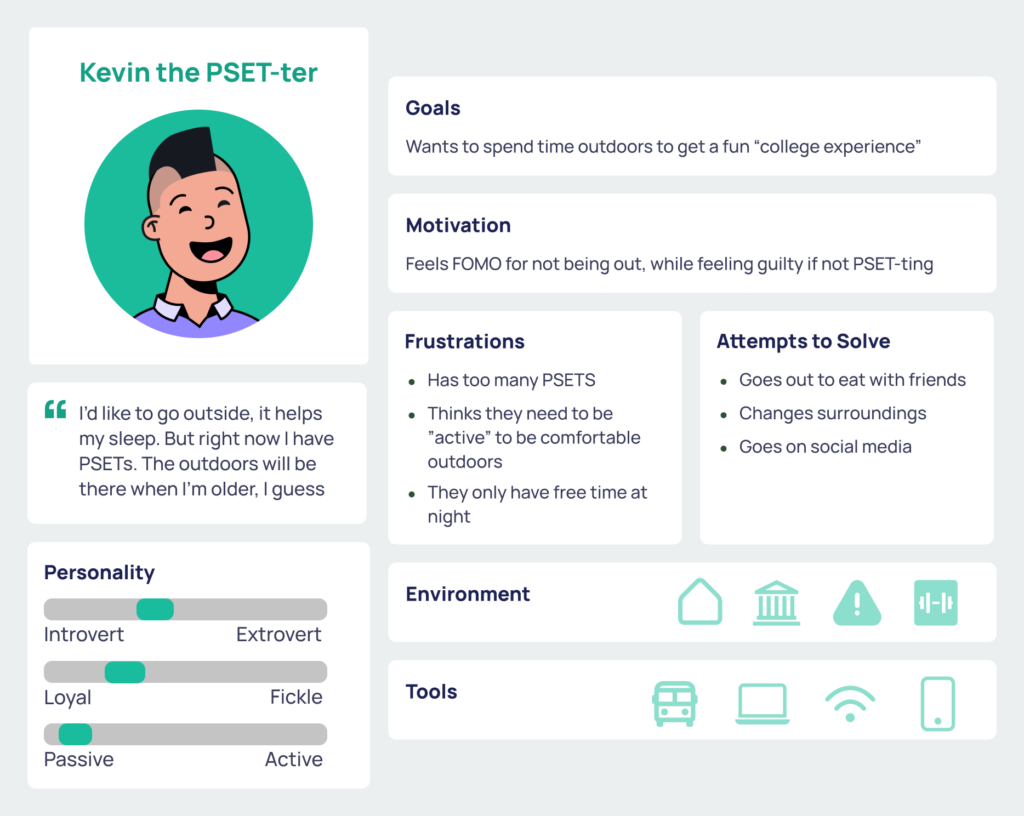

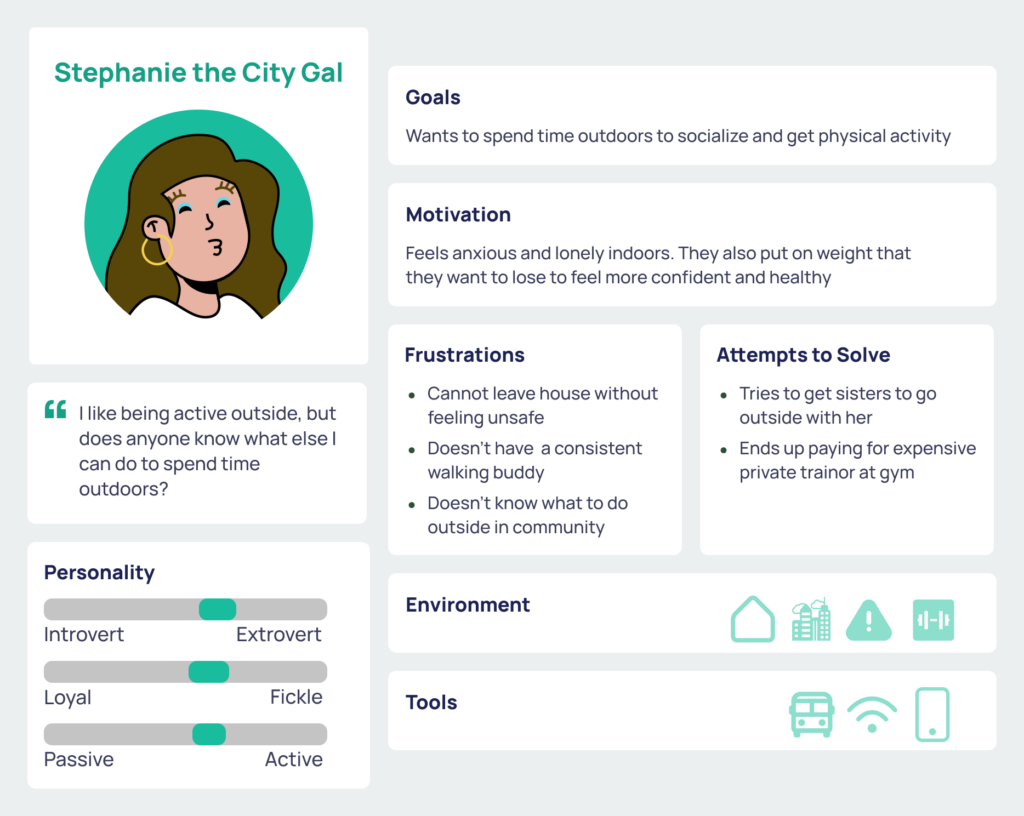

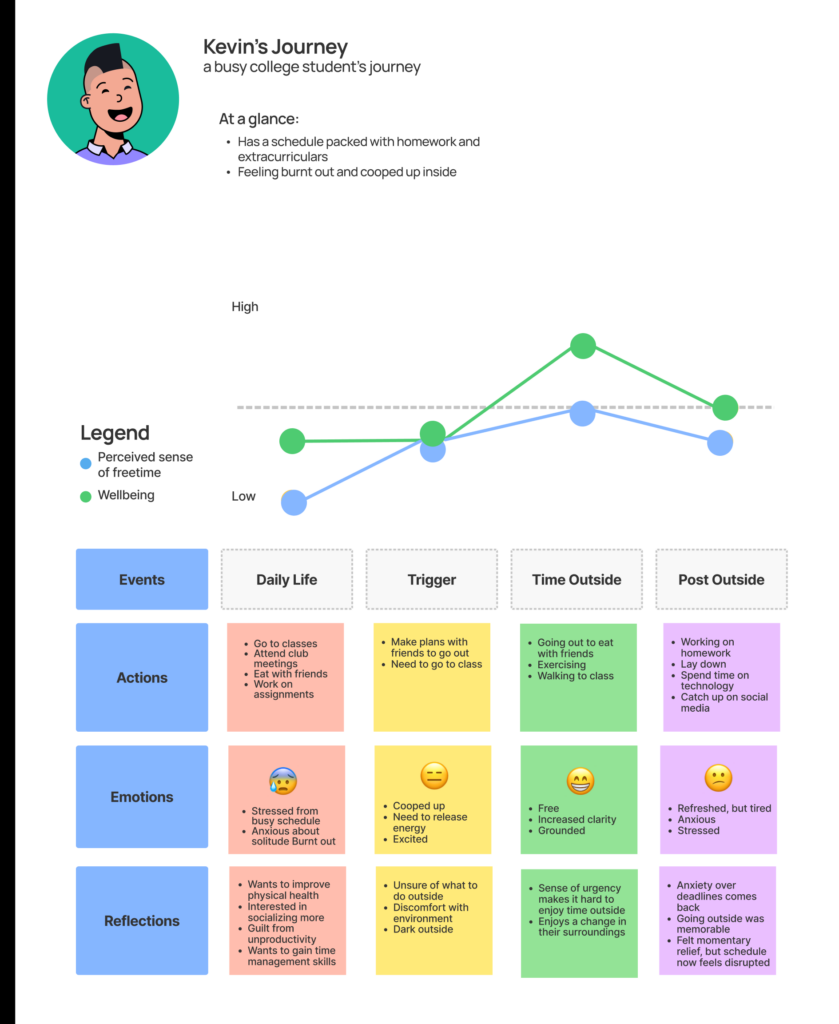

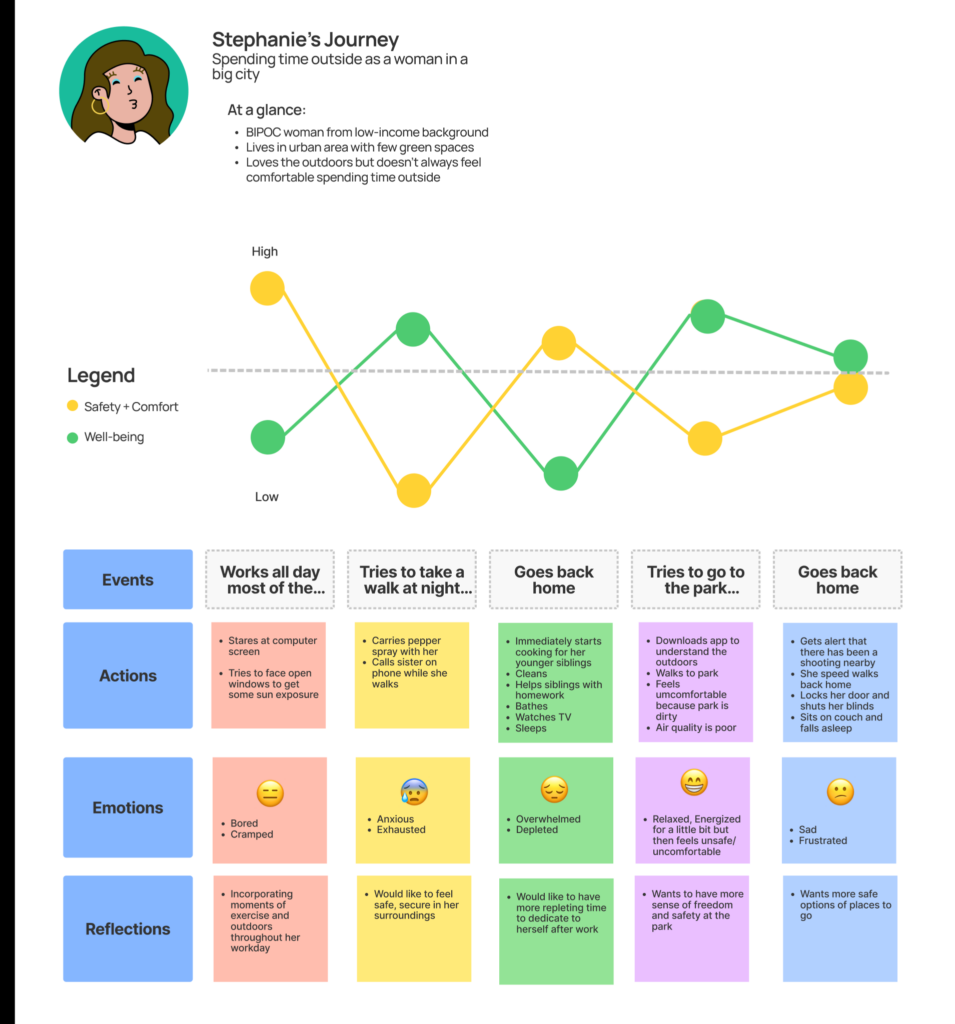

After reviewing our data, we narrowed our problem space to two dominant personas: Stephanie, the city girl who enjoys being in nature but lives in an urban environment and Kevin, the busy PSETer who wants to spend time outside but never makes time for it.

From Stephanie’s journey map, we learned her main goal is to feel a sense of freedom and mobility outside her home, but she feels a conflict between her love for spending time outdoors and her safety and comfort. From Kevin’s journey map, we learned his main goal is to improve his mental and social well-being by spending leisure time outdoors, but he feels a conflict between knowing that spending time outside is good for him and and constantly pushing off going outside because he de-prioritizes it compared to his work.

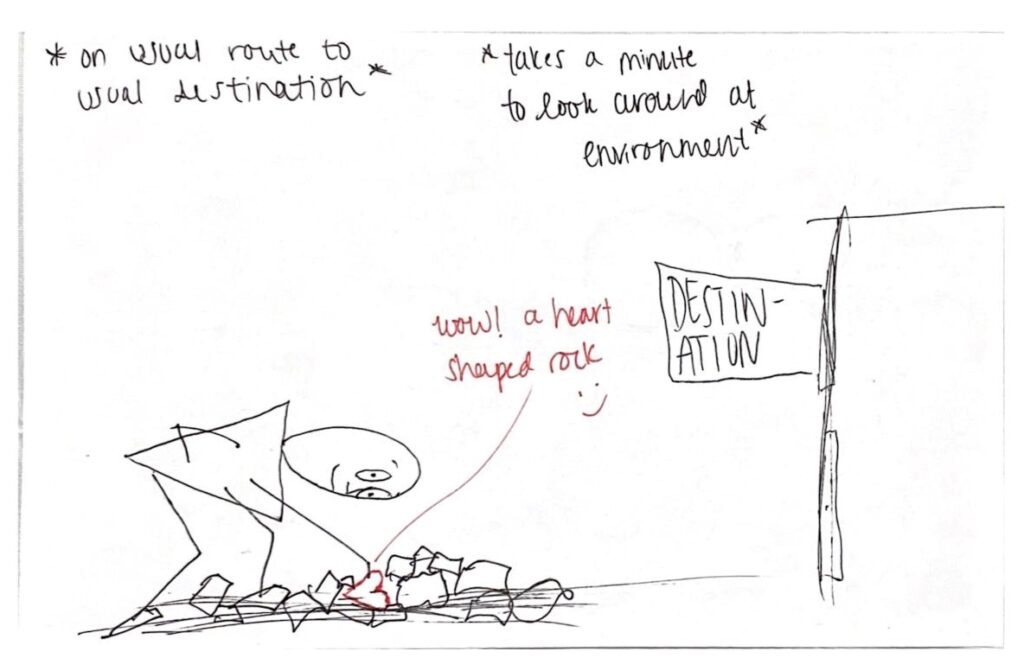

From these two journey maps, we drafted storyboards that centered these conflicts of perceived sense of comfort and perceived sense of time. From these expanded narrative tools, we realized that as we developed our solutions, we wanted to leverage intentional social activities, as we saw that having a planned outdoor activity with buddies improved users’ comfort being outside and accountability to execute plans to get outside.

Solution Finding

Ideating and Picking an Intervention

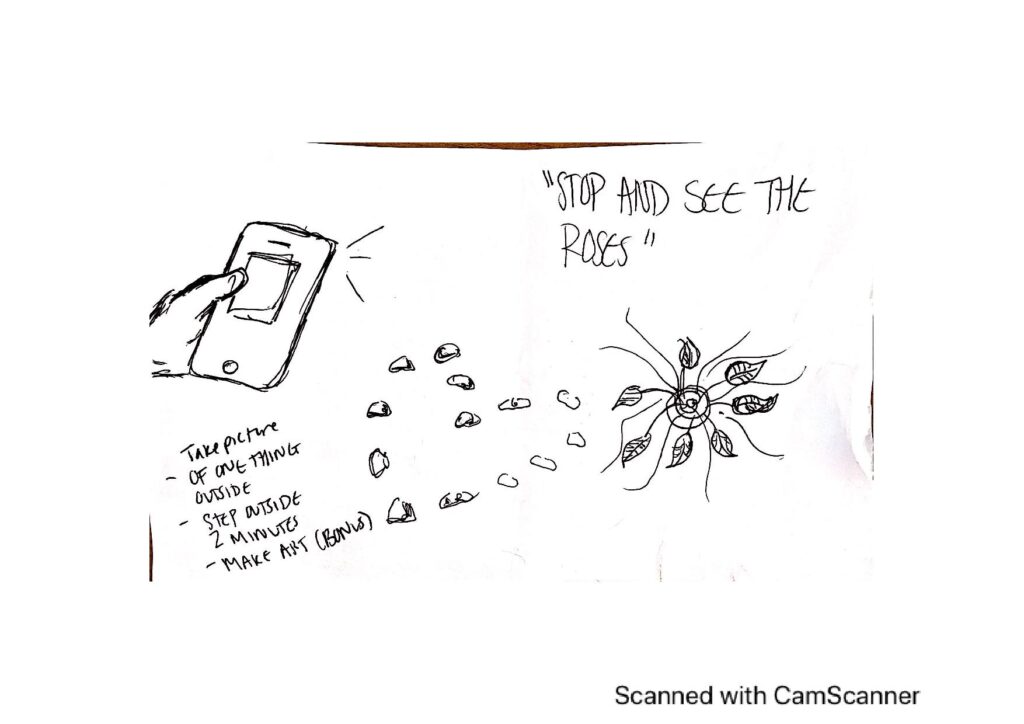

The exercises that our team completed during the brainstorming phase of our project helped establish the purpose of our project–we now had a problem to solve and the means to solve it. How, then, do we use our findings to help get people outside more often? With our baseline study data and personas in mind, we took our first step into the solution space through creating ideation cards. We honed in on exploring the elements that make up our ideal outdoor experience; that is, we focused on outdoor engagement, safety, accessibility, and convenience.

Our ideation cards were focused more on the user behavior that we wanted to encourage rather than the ways in which our product would intervene in their experience. From this, we worked together to brainstorm how a product could bring all of our ideas together into one cohesive experience, and we decided that a daily challenge-based intervention was the right direction to head in.

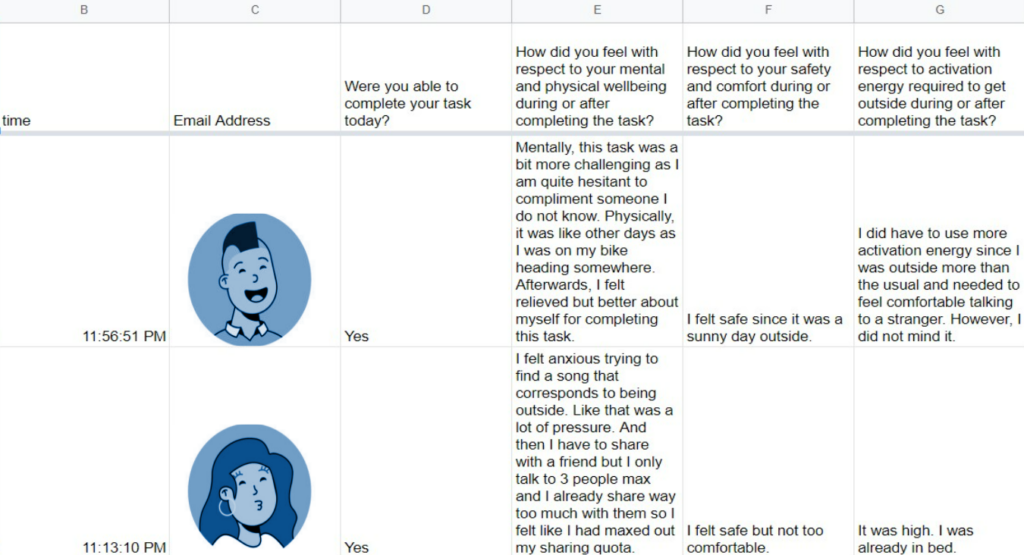

Intervention Study

As we began creating our intervention study, we designed with the goal of answering two lingering questions:

- How do we balance outdoor engagement and activation energy?

- To what extent can social components address issues of safety and comfort outdoors?

Our intervention study took place over the course of 5 days, and each day we prompted our participants to complete a 15-minute challenge outside and a reflection of their experience. We asked them to do things such as taking a picture of a pretty flower or spend quality time with a friend outside, and we gauged the success of each task based on their responses regarding mental wellbeing, activation energy, accountability, and safety.

We learned a lot from our intervention study; for example, while we previously considered a stranger-matching service to address accountability, our study showed us that that idea would have had a very negative impact on our user’s feelings of safety. In all, we learned that people respond positively to medium-activation tasks, and that while social tasks increase accountability, they should be used sparingly to avoid overwhelming our users. If we were to run this study again, we would want to explore personalization a bit more thoroughly through:

- Onboarding that would help us design challenges specific to a user, and

- Using the time of day to assign challenges more appropriately.

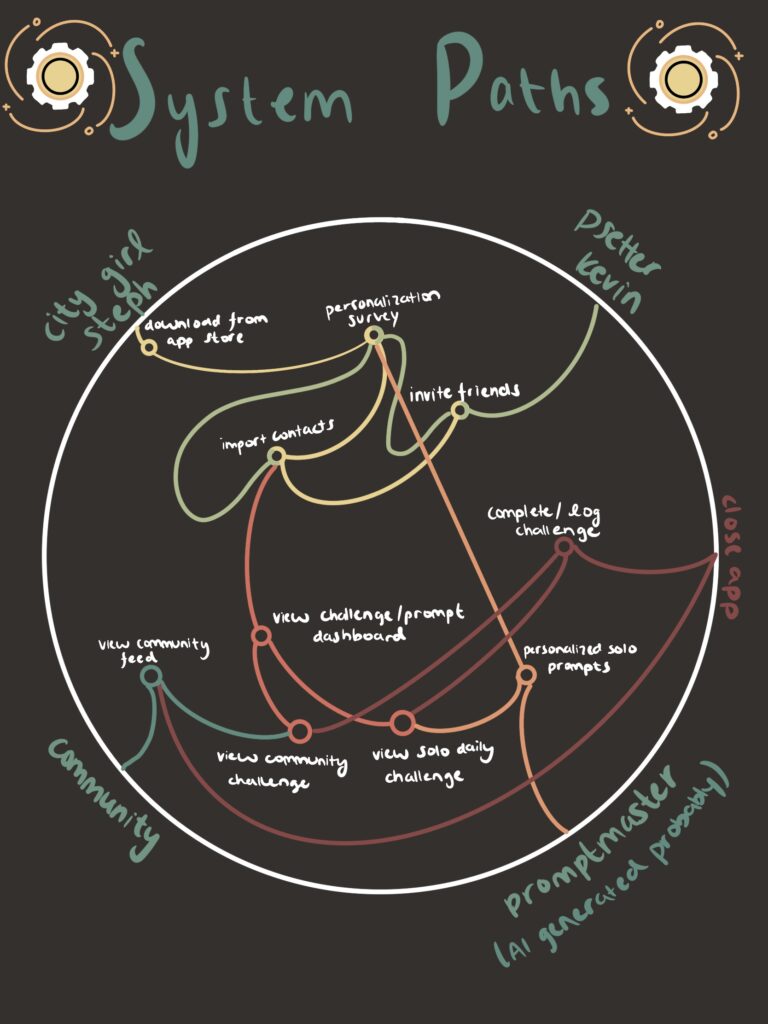

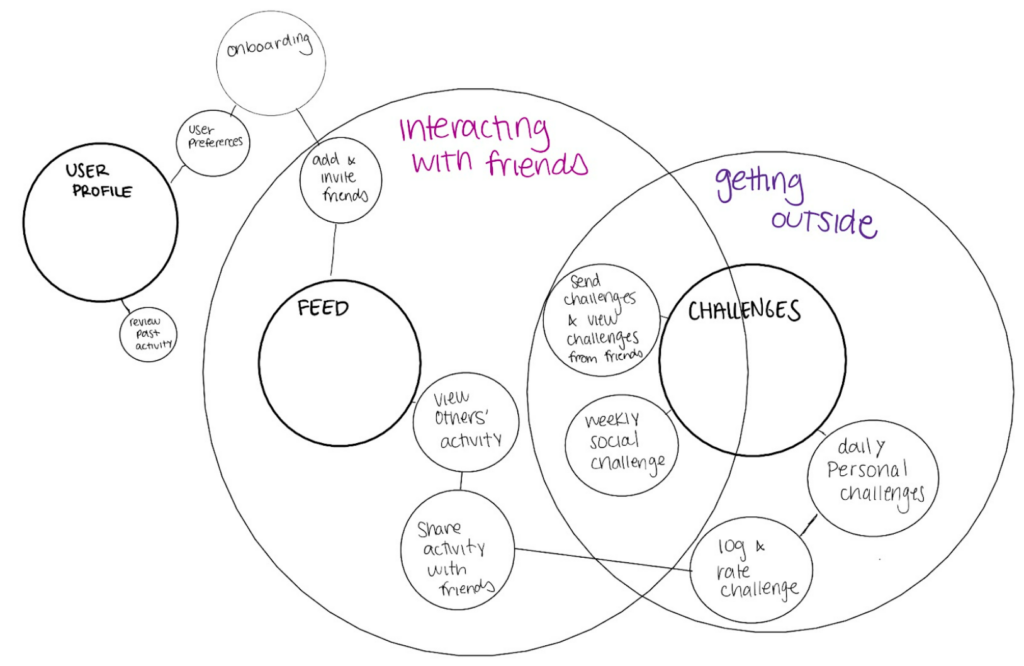

Mapping

Different mapping activities allowed us to flesh out some of the more important components of our application and get a better understanding of how each part should work together to form a cohesive experience. One of the more valuable mapping activities to our project, and the one that we all said we would use again, was the system paths diagram–it sparked a lot more conversation and debate about what we expected the flow for our app to be, and it helped to join us together in our visions for the application.

The bubble map gave us a different, but equally important, view of our application. While our system path diagram helped to depict the story of a user’s experience as they navigate our application, the bubble map gave us a broader perspective of the different key components of our application and how they interact with each other.

Both mapping techniques helped in grounding the three main portions of our envisioned app: the onboarding (personalization), the challenge dashboard (prompts to go outside), and the community feed (social accountability).

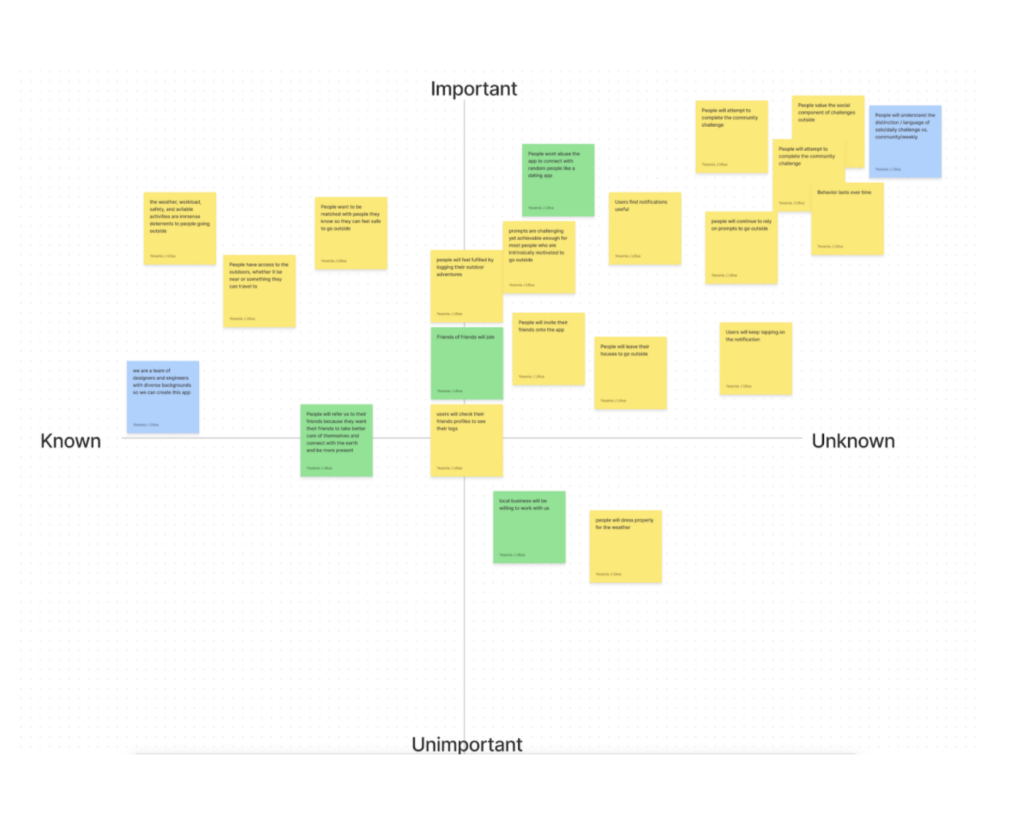

Assumption Mapping

After getting a better understanding of how a user would navigate through our application and how our separate application components would have to come together to form their ideal experience, we began considering our existing assumptions.

We mapped out our assumptions regarding how people would interact with and the success of our application, the most severe assumptions being:

- Daily challenges will be appropriate in providing long-term motivation for our users.

- People will value the social component of challenges outside.

We conducted experiments based on our assumptions, and we found that:

- Personalized challenges made tasks easier to complete,

- challenges that can be easily integrated into an everyday schedule are more motivating,

- and social challenges are appropriate only when an appropriate window of time is given in order to organize and complete the challenges.

Designing Paseo

In creating our wireflows, we started to design the different screens for onboarding and viewing challenges, profiles, and user activity. Through this process, we had various questions to tackle such as “What is necessary for onboarding?”, “How do we ensure that Paseo doesn’t feel like a social media app?”, and of course “What are all of the screens we need to include?”.

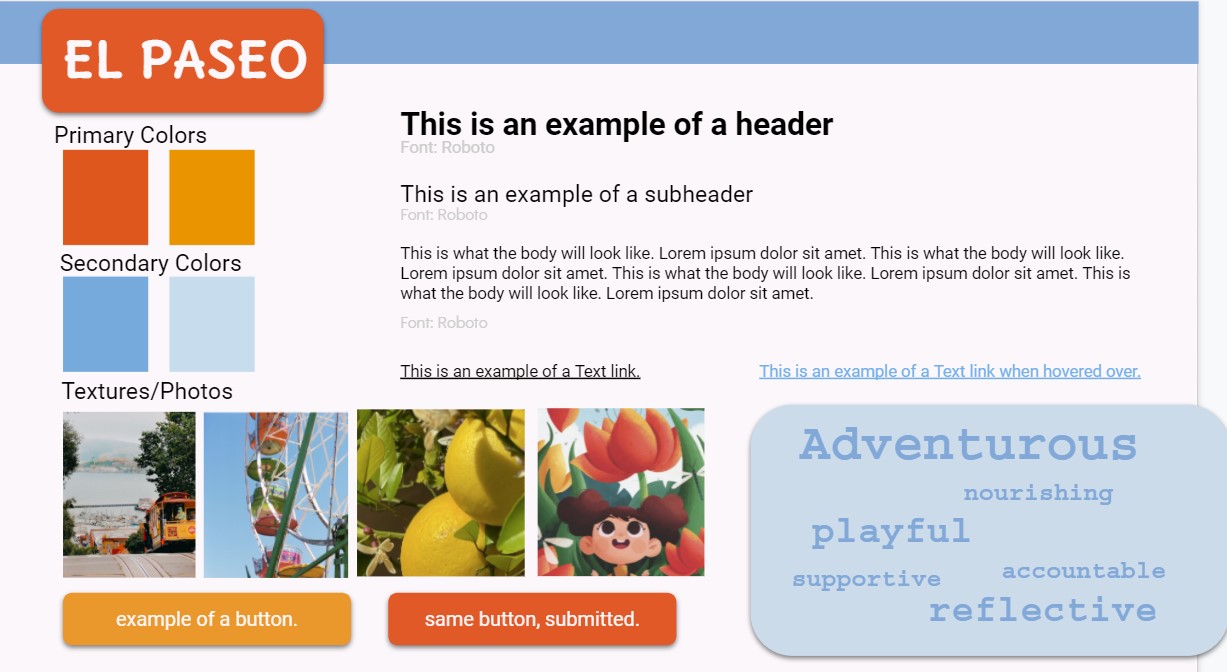

After getting our initial thoughts down in our wireflows, we next worked on our mood board and style tile to form a cohesive look and feel for our app. Although we found ourselves drawn towards typical outdoorsy colors such as green and brown, we ended up centering our app on oranges and blues due to their playfulness.

After establishing an aesthetic vision for our app, we moved on to developing our wireflows into sketchy screens. When creating our sketchy screens, we started to form a unified design system for our app – utilizing a toolbar at the bottom to navigate between screens and identifying different modules.

We then were able to raise the fidelity through our clickable prototype. In creating our clickable prototype, we were able to more clearly envision what it meant for a user to use our app. We also worked even further to unify our app’s design, creating different modules on Figma to be used throughout our app.

Once our clickable prototype was complete, we were able to proceed with usability testing. When completing usability testing, we heard insightful questions from our peers that informed our later design. Notably, we encountered confusion about onboarding questions related to social identity and the differences between community and solo challenges as well as frustration with submitting time preferences. With this in mind, for our final prototype we aimed to provide more explanation for different form submissions throughout the onboarding process, such that users can understand why certain questions are posed. We also worked to make clearer distinctions between the community and solo challenges, brainstorming potential language that could be changed to reduce confusion. And when it came to users submitting time preferences, we altered our design to ask users if they prefer morning, afternoon, or evening nudges as opposed to asking for an hour by hour breakdown of their days.

The Ethics

Nudging and Manipulation

In order to change the behavior of users, our app focuses on the use of nudges as well as the extrinsic motivation associated with one’s social circle. By utilizing one’s location and time preferences, efficiently timed notifications can be sent to users in order to nudge them outside. Unlike nudges such as junk food at a grocery store checkout, these nudges are sent in an effort to improve one’s behavior – as opposed to making profit or an underlying malicious intent. Our nudges also aim to be encouraging, with our app itself additionally revolving around the power of reflection and intrinsic motivation. If our project were to instead use an approach similar to DuoLingo, or to use an extensive amount of gamification, nudges may instead feel manipulative as if users have to participate in using our app.

Privacy

Our project respects user privacy by hinging on opt-in as opposed to opt-out services. We aim to be up front with users about what data we are accessing, in addition to why we are accessing it. Our app also aims to protect user privacy by keeping user profiles private to those who are not on their friends list. We also only allow for users to mutually access each other’s profiles/activities, as opposed to allowing for users to follow someone without permission or being followed back such as on Instagram or Twitter. The premise of “community challenges” however may be harmful for user privacy. Because these challenges are global to everyone in the app, it may become easy for users to track other users’ activity and to know what they are doing, where at, and at what time. In order to combat this, we may aim to keep these challenges more open ended as opposed to specific, such that it is unlikely for users to have this sort of activity revealed to others they may not want to share this with.

Design for Well-Being

Paseo promotes well-being by promoting the physical and mental health of users through increased time spent outside. If the challenges promoted by Paseo are too daunting or feel obligatory to users as opposed to encouraging, the well-being of users may be adversely affected because of stress associated with Paseo. We hope to combat this however through the creation of challenges that require a low amount of activation energy.

Broader Impacts

If the behavior change proposed by Paseo were to be widely adopted, we would see many more people intentionally spending time outside, and less time inside and/or on technology. With this, we’d also hope to see improved mental and physical health of users/society.

Conclusion

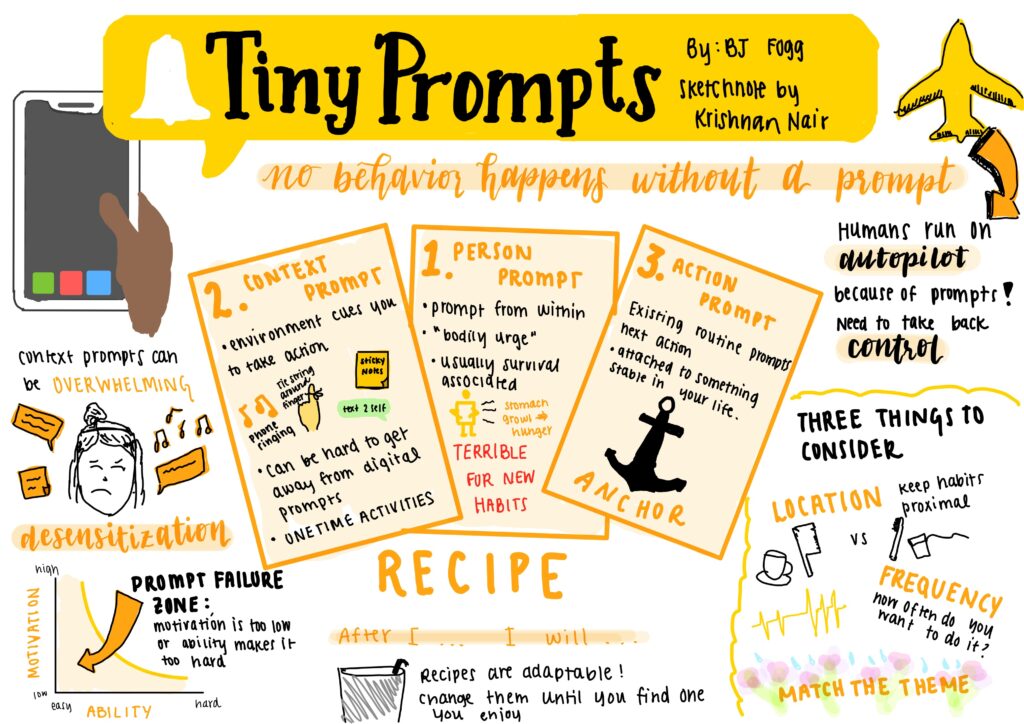

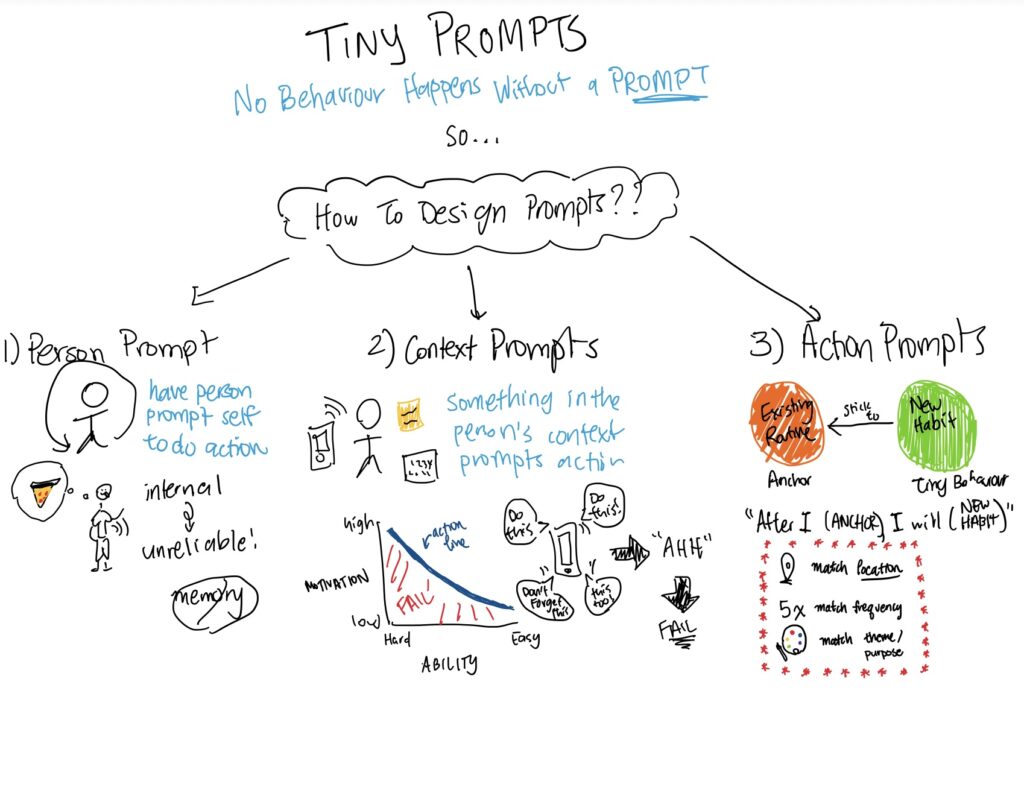

In summary, this past 10 weeks, team 9 synthesized theoretical concepts from advanced design tools, behavior change literature, and technology ethics and applied it to a relevant, real life problem of getting people to spend time outside. For example, we were able to apply habit change frameworks such as the action line model, as balancing optimal activation energy was the foundation on which we centered our solution where delivered two modes of activation energy to serve users’ needs: daily, low activation energy solo challenges and less frequent, weekly, high activation energy social challenges. We also used advanced synthesis techniques like causal connection circles, which gave us rich information on the positive and negative feedback loops of why people spend time outside or avoid it, by linking relationships between various factors like time of day, sense of safety, sense of time, transportation options, and social groups. Finally, through constant discourse on the role of designers for social justice, we considered questions like how to weigh user’s privacy of information, to make decisions like keeping social identities in the onboarding profile but making it optional to allow users of similar identity to find comfort in one another or to skip the question if it makes them uncomfortable. As we approach our next behavior change efforts, we will bring with us our robust CS247B toolkit of: models for understand behavior change, design thinking tools for insight synthesis, and centering what our ethics principles are throughout the process rather than as an afterthought.